A Brief Argument for Short Books

7 Reasons to Love Short Books—Plus 16 Slender Specimens to Try on for Size

I like big books (and I cannot lie).1 But I also love short books and generally believe an author who serves the world something both complete and compact has done our entire species a wonderful service.

It’s not that hulking, sprawling tomes are inherently problematic. Like seemingly everyone and their Aunt Sally I recently read Middlemarch (nearly 800 pages) and loved it. What’s more, I just finished reading Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed (about 650 pages) and loved it as well; the humor, the characters, the plotting, the reversals, the whole crazy mess is pure delight. If an editor had somehow forced Manzoni to cut it down, I’d travel back in time and strangle him.

And yet! There’s so much to recommend a slim read.

My Brief Argument

In fact, here are seven reasons to appreciate short books and intentionally make room for more of them in your life. The braver among us won’t care about this first reason, but it’s got its merits:

Short books feel less intimidating. Because of the length, we’re more likely to both start and finish a slip of a book. And finishing quickly builds momentum while boosting confidence—and appetite—for more.

Short books encourage experimentation with new authors, subjects, and genres. Go ahead: You’re not giving away three weeks of your life; maybe just an afternoon.

We’re more distractable than ever, and shorter books pair well with shorter attention spans. I know some of you hate this reason, but let’s be real. Middlemarch is still there. In the meantime, there are lighter books that make lesser demands. There’s no virtue in being martyred to aspirational reads, especially if you’ll just bounce and check Instagram anyway. That leads directly to the fourth reason.

Short books require us to mentally juggle fewer elements, making the reading experience easier to manage. You don’t have to keep straight dozens of stray plot points or random characters who boomerang back on you three chapters after you forgot about them.

And they’re not only cognitively less demanding; they’re also physically less imposing. Short books are easier to carry, so we actually read more during the interstitial moments of our day. They slide into the nooks and crannies of real life: getting coffee, waiting in line, taking a bath, jumping a flight, or laying in bed.

Their brevity tightens their focus. Authors who write short have to write sharp. I’ve never forgotten George Will’s description of David Frum’s Dead Right: “As slender as a stiletto and as cutting.” That’s not just a statement of style. Short page counts require authors to distill and concentrate. Readers benefit from the focus.2

Finally, short books are easy to reread, which can enliven our experience and deepen our understanding. If it only took you an afternoon to complete, there’s no problem taking an evening to run through it again—to reengage, to read closer, to pick up what might have been missed the first time through.

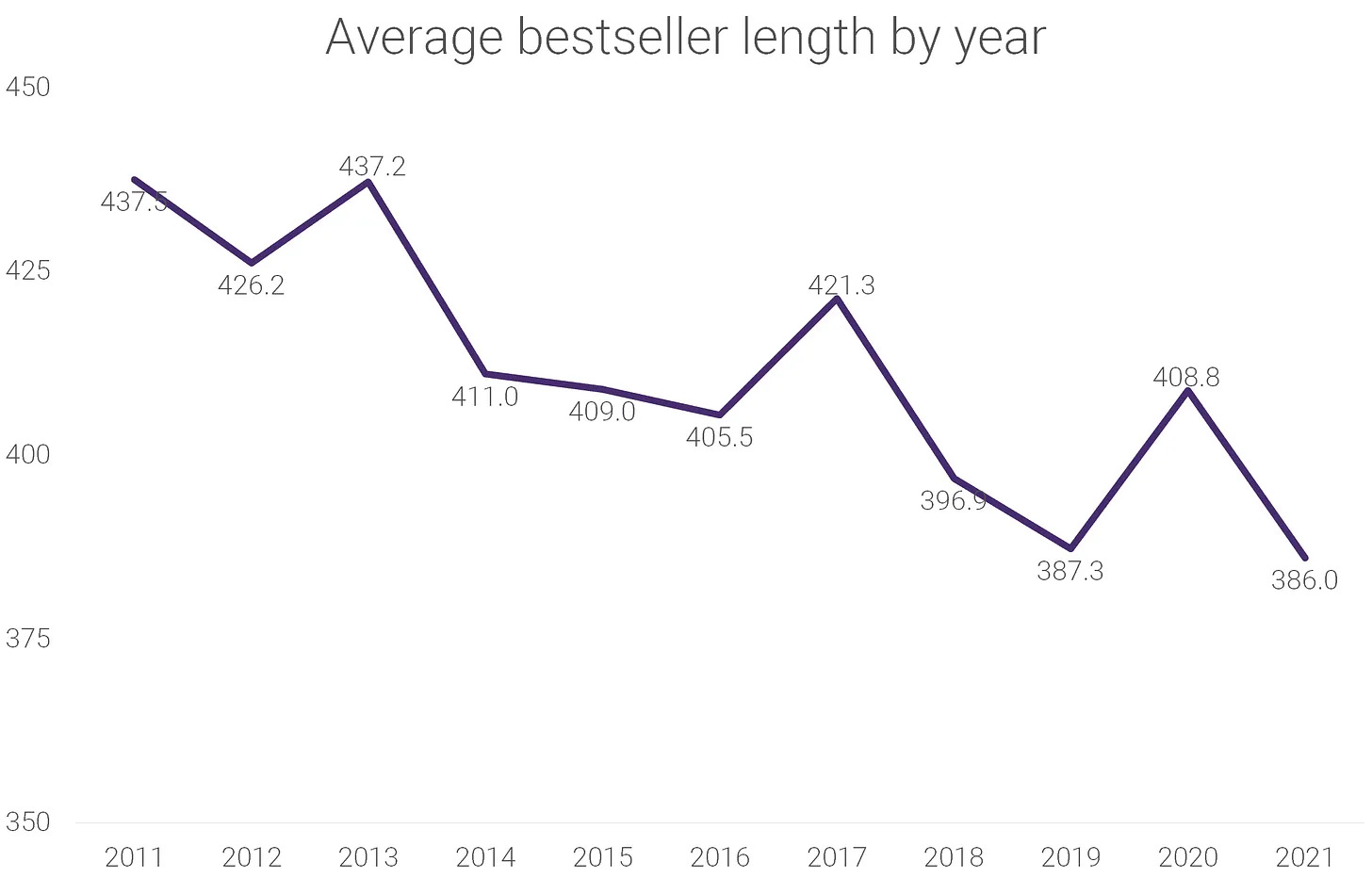

None of this means you shouldn’t read long books—just that there’s no good reason to snub a shorty. And I’d say the market seems to echo the point. Bestselling books are getting shorter and shorter, according to one study of almost 3,500 New York Times bestsellers from 2011 to 2021.

The reasons appear to track with some of the list above. “The digital age brought a huge increase of various types of content fighting for people’s time and attention,” says researcher Dimitrije Curcic. Shorter books are well suited to a world of high competition from digital media.

A Possible Shopping List

With that in mind, here’s a list of easily digestible classic novels, perfectly attuned to the present moment and listed in descending order by page count. If I’ve reviewed the book, I’ve included the link.

197 pages: Cormac McCarthy, Child of God

180 pages: F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

168 pages: Sabahattin Ali, Madonna in a Fur Coat

163 pages: G.K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill

159 pages: Willa Cather, O Pioneers!

157 pages: Graham Greene, The Third Man

154 pages: John Wyndham, Chocky

152 pages: Shirley Jackson, We Have Always Lived in the Castle

150 pages: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Sufferings of Young Werther

144 pages: Pär Lagerkvist, Barabbas

128 pages: Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

120 pages: Nella Larsen, Passing

114 pages: Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha

107 pages: Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

89 pages: Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (review coming this Saturday!)

73 pages: Osamu Dazai, The Beggar Student

That’s about 2,300 pages in all. I’ve got nothing against Atlas Shrugged or Don Quixote or War and Peace. But sometimes you just want a lark, not a long-term project. Nothing wrong with that.

And as long as we’re here, tell the rest of us: What’s one short book you love?

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please share it with a friend!

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe. It’s free and might even improve your credit score. (No one has reported any such improvement thus far; still, you never know.)

You’re welcome.

This takes nothing away from the expansive narrative into which a reader can dissolve like a bag of bath salts while luxuriating amid the eddies and currents of boundless imagination. But sometimes you just want something that zaps.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Short stories are also a great way to get to know an author. I read Tolstoy’s novels before reading his short stories but I wish I had done the opposite. Tolstoy was a prolific writer of short stories and it helps to get used to his style and things like patronymics and diminutives. Keeping track of his characters in the longer novels is hard without being used to these aspects of his writing.