Give Us Barabbas! We Are Barabbas!

Reviewing Pär Lagerkvist’s Classic, Nobel-Winning Novel ‘Barabbas’

After the phlebotomist stuck me twice without result, she went to get some help. In walked the most experienced woman at the lab with a trainee in tow. As she poked and probed the inner bend of my arm, looking for the best possible vein, she noticed the book I’d brought with me: Barabbas by Swedish novelist, poet, and playwright Pär Lagerkvist.

“Tell me about your book. How is it?” Was she trying to take my mind off the coming jab?

I gave a quick summary of the premise, that the story follows the life of the criminal Barabbas after he finds himself pardoned by the Roman governor Pilate while Christ goes to the cross instead. I couldn’t say much more before she found the vein she was after and—wince!—plunged in the needle.

I decided to read Barabbas during Lent, given the story’s connection to the Easter season. Nick Gillespie mentioned it on the Reason Roundtable late last year, and the author’s name rang a bell: I recalled seeing a copy of Lagerkvist’s earlier novel The Dwarf on my grandfather’s shelf.

The son of Swedish immigrants, my grandfather maintained a strong cultural connection to Sweden. He relearned the language as an adult, traveled to Sweden with my grandmother, and joined the local Vasa lodge at home; he loved taking us grandkids to Maypole dances. If I had known to look for it, Barabbas probably sat upon Grandpa’s shelf as well.

Lagerkvist was a literary giant in Sweden. He wrote more than a dozen plays and poetry collections, several collections of short stories, and nearly a dozen novels. He was a member of the Swedish Academy and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1951 on the strength of all that had come before, but especially on Barabbas which was published the prior year.

Free But Unfree

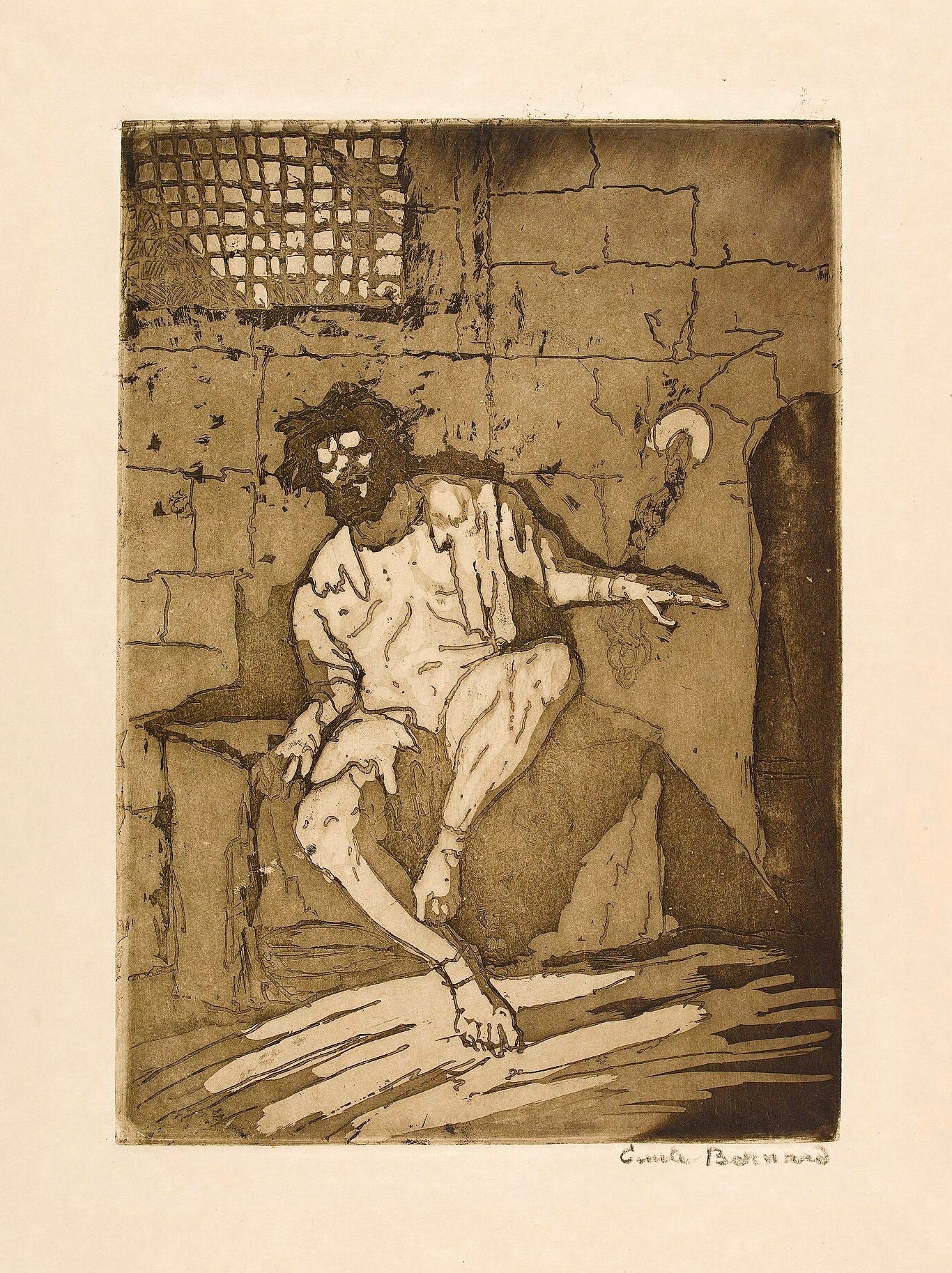

The story starts with the crucifixion of Christ and a quick description of the onlookers: his mother Mary, Mary Magdalene, Veronica, Simon of Cyrene, Joseph of Arimathea, and one more man, mostly out of view, as if he were hiding, Barabbas, who should have been hanging from the cross himself but walked free because the crowd chose Jesus.

What would that be like, to stand condemned and yet find yourself acquitted and free, pardoned and loosed of your bonds? In Lagerkvist’s telling, it’s a fearsome burden. Barabbas is a slender novel, just 144 pages in the Vintage edition, but it’s freighted with existential weight. Though set free, Barabbas finds himself tethered to Christ, haunted by his memory, and unable to escape his influence.

He finds himself drawn to the gatherings of Christians, their gossipy pockets and clusters in the streets, their formal assemblies. He has an unpleasant run in with St. Peter, foreshadowing a much different encounter later in the book.

A hare-lipped woman with whom he had a relationship feels drawn to Christ. She’s heard rumors of his third-day resurrection and waits by the grave. Barabbas, bedeviled by the same rumors, waits at a distance, eyes on the tomb. Something happens; he’s unsure of what, but suddenly the stone barring the entrance is gone. A trick of the light? Was it already rolled back when he arrived? His disciples have done it and stolen the body. But have they?

The hare-lipped woman says he’s been raised from the dead. She saw an angel descend and roll back the stone. Barabbas can’t accept that but later finds her testifying amid a group of Christians. Shortly after, she’s accused of blasphemy and stoned like St. Stephen. Barabbas witnesses her death, retrieves her body, and buries her.

Nothing he’s experienced since his acquittal makes sense to him. He tries returning to his life of brigandage but finds it unfulfilling and wanders off—clean out of the narrative.

Lagerkvist skips over a few decades and brings us back when Barabbas is older, grayer. He’s now enslaved, shackled to another slave in the copper mines. The man knows little of the new faith but calls himself a Christian. He wears a slave medal around his neck that says he belongs to Caesar. On the reverse of the medal, however, he’s etched the name of Christ.

Barabbas asks to have Christ’s name carved in his medal as well but regrets the choice shortly after making it. He can’t bring himself to pray. When circumstances haul them before the authorities, Barabbas’s partner testifies like the hare-lipped woman, while Barabbas betrays Christ like St. Peter and watches his friend be crucified.

Though he’s still enslaved, events soon take Barabbas to Rome. The Christians are there as well; he can’t escape them! When a conflagration engulfs Rome in flames, he finds himself drawn to the fires and joins in torching the city, perversely hoping to help Christ remake the world. Captured, he’s rounded up with the Christians, accused of arson, and sentenced to death. Barabbas dies like the man whose death set him free, and his final utterance might even betray a desperate hope.

Reading Barabbas Today

Lagerkvist wasn’t a conventional Christian, but his novel works with themes any Christian would recognize, including unmerited grace, the ache of God’s absence, the ambiguity of belief, and martyrdom. And it can go deeper. Barabbas’s life represents a sort of upside-down gospel. Instead of redemption, Barabbas experiences refusal. Instead of clarity, he experiences confusion.

But this little masterpiece welcomes many other interpretations as well. Consider its existentialist reading: Barabbas represents the struggle to find purpose and amid the randomness and absurdity of life. He should have died. By chance he lived. But what comes next taunts him. Unable to make sense of his situation, he drifts through life bereft of meaning.

There’s a psychological reading in which Barabbas endures a form of survivor’s guilt and struggles to make sense of his life after the trauma. His fixation, confusion, and inability to answer the nagging questions about the central event of his life—Christ’s death effectuating his freedom—conveys his psychological disintegration.

The book even welcomes a libertarian reading in which the power of the state distorts human striving, arbitrarily robs people of life and freedom, and corrupts their daily experience. Barabbas finds himself trapped within an oppressive, authoritarian system, stubbornly resistant to the end.

While the book is now seventy-five years old, Barabbas is remarkably modern, playing with themes we experience on a daily basis: the crisis of meaning, isolation and loneliness, violence and political oppression, trauma and guilt, authenticity and identity. While reading it, my mind returned to Shusaku Endo’s novel The Samurai several times; the two books make a remarkable pairing.

When the phlebotomist asked me about Barabbas, the trainee who shadowed her admitted, “I don’t even know who Barabbas is.”

I should have responded by saying, “I am.” We all are.

Thanks for reading! Please hit the ❤️ below and share this post with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

If Barabbas sounds intriguing, don’t miss Shusaku Endo’s novel The Samurai, reviewed here.

I remember reading Barabbas as an undergrad, while also leaving the Christian faith. That copy was lost many years ago, but I found another, similarly worn, at Bart’s books in Ojai. I need to read it again, thanks for the reminder 😊

Thank you for this review. All I have known of "Barabbas" in culture is the movie starring Anthony Quinn. I never realized it was based on this book, but I looked it up and the author is credited with helping write the screenplay. I am confident that, as usual, the book is far superior to the movie!