Bookish Diversions: When the Internet Was Analog

Whole Earth Catalog Online, Tyler Cowen’s AI Book, Paperbacks, Audiobooks, Sam Bankman-Fried’s Accidental Defense of the Humanities

¶ The first internet? It was analog, made up not of silicon and fiber optic cables but of clay tablets and sandal leather. The primary purpose of ancient libraries and archives, according to Ancient Near East scholar Eleanor Robson, “was to provide large datasets” to assist learning and decision-making, especially for kings and priests.

Eventually, the systems administrators upgraded the hardware to papyrus, but the basic purpose remained the same. The Library of Alexandria was, as historian Dennis Duncan put it, “Greek Big Data.”

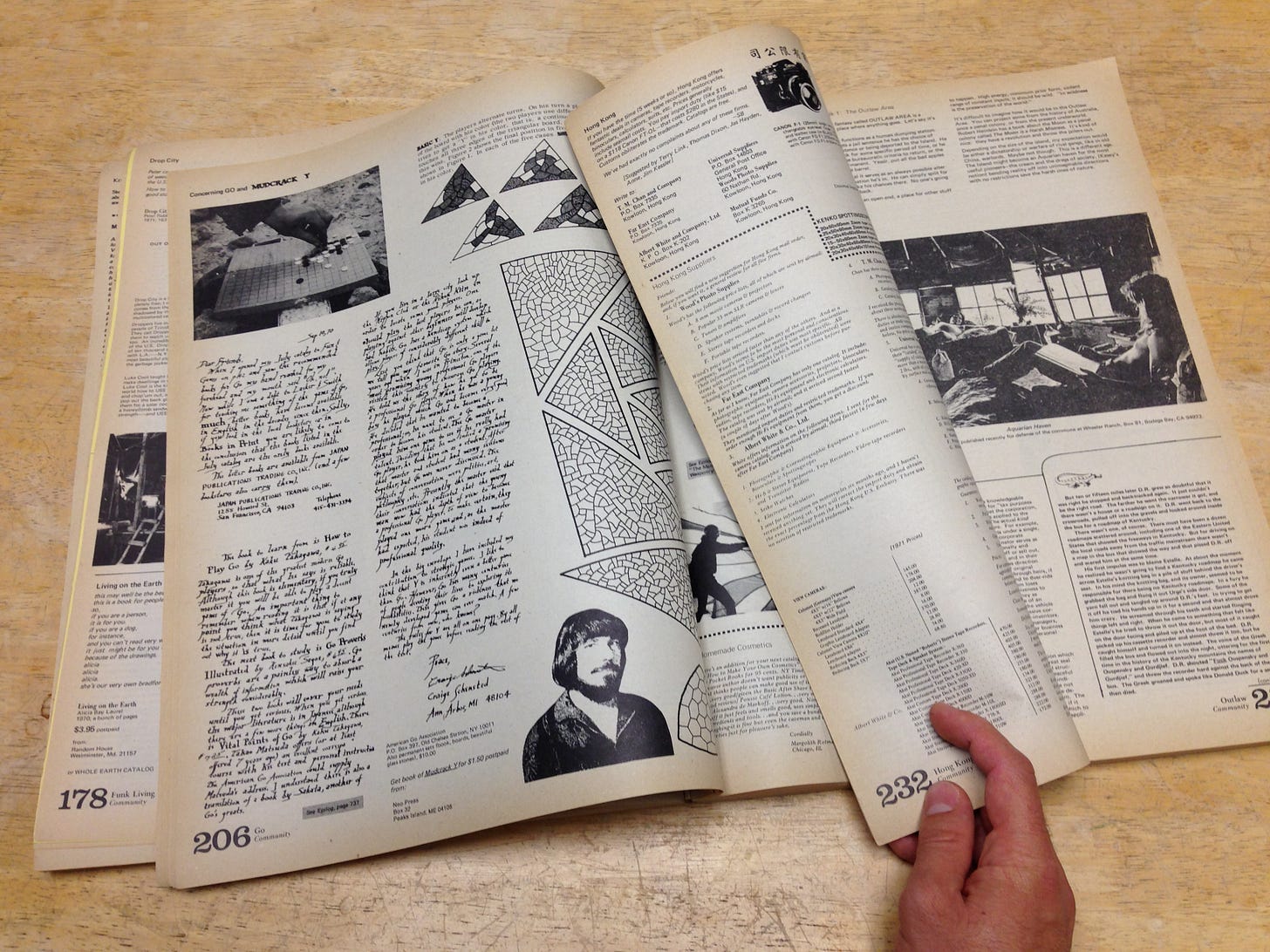

You can follow this trajectory all the way through Medieval and Renaissance libraries to Diderot’s Encyclopedie, its modern descendants, and Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, which began its remarkable life fifty-five years ago in Fall 1968.

Advertising “access to tools,” the counterculture publication featured articles and product reviews that helped shape the emerging DIY, hacker, techno-libertarian ethos of Silicon Valley. “The idea of the Whole Earth Catalog in the ’70s was to confer agency,” says Brand.

So you went from being passively disinterested to becoming actively interested in a lot of things. Every one of those reviews was like a half-open door of something you might well do with your young life. A lot of people went through those doors.

They sure did. “When I was young,” recalled Apple cofounder Steve Jobs in his 2005 Stanford commencement address,

there was an amazing publication called The Whole Earth Catalog, which was one of the bibles of my generation. It was created by a fellow named Stewart Brand . . . and he brought it to life with his poetic touch. This was in the late sixties before personal computers and desktop publishing; so, it was all made with typewriters, scissors, and Polaroid cameras. It was sort of like Google in paperback form, thirty-five years before Google came along. It was idealistic, overflowing with neat tools and great notions.

The Catalog had legions of loyal readers and made a resonant statement to the wider culture. Its June 1971 edition, the so-called Last Whole Earth Catalog, won the National Book Award in 1972 for Contemporary Affairs. Last was a misnomer. Brand went on publishing occasional updates into the late 1990s and spawned a small universe of sister publications as well, including CoEvolution Quarterly, Whole Earth Software Review, and others.

And now it’s all—or mostly all—online. “It literally hadn’t been scanned anywhere, and the stuff was impossible to get,” said Gray Area executive director Barry Threw, who led the digitization initiative with the Internet Archive.

While decidedly of its time (and place: the San Francisco Bay Area) the archived Catalog, available with its sister publications at Whole Earth Index, represents a “primary source look at a history of intellectual discourse and countercultural thinking in the Bay Area, which includes cultural expressions that I think that we’ve lost,” says Threw.

¶ Make your own at home. The very publication of the Catalog exemplified its DIY approach to life. In a wide-ranging conversation with economist Tyler Cowen Brand talked about the design and production process. “I stole everything,” said Brand about the design.

The Windsor typeface I used on the Whole Earth Catalog . . . . That was the L.L. Bean-type font that they used. I was building on my father’s interest in mail-order catalogs, and L.L. Bean was one of the ones we really liked. There was a straightforward New England honesty about it that I really appreciated.

What about the typesetting and layout?

A couple of things made possible self-publishing a book that ambitious, and one of them was the IBM Selectric composer. It was the golf ball striker, where you could take one golf ball that had all of the letters on it in a particular size and font and put on another one in italic or whatever. You could do very complex typesetting with basically a jumped-up electric typewriter. That let us do really good compositing right there in real time.

Likewise, photography. Getting halftones — there was a brand-new device that would let you make halftones. Lots of times, we just clipped stuff out of magazines and books and just pasted it down. Then the paste stubs — we originally used beeswax in a big old electric frying pan with melted beeswax, and we just pasted that on and slapped it down on the page. That was how we laid it out.

Of course, now we’re all doing it on Substack—no beeswax necessary! But it was self-publishing pioneers like Brand that made that possible. The whole interview with Cowen is worth watching for a window into Brand’s mind. You can watch below or read the transcript here.

¶ Manual for Civilization. Brand’s interests have only grown in scope since the end of his Whole Earth days. Through his involvement with the Long Now Foundation, Brand advises we think ahead—roughly 10,000 years. One of Long Now’s projects? A 10,000-year library, what they call the Manual for Civilization.

Here’s Brand back in 1999, floating the idea:

What on earth would something aspiring to be a 10,000-year library be good for? One answer might be that it would provide, and even embody, the long view of things, where responsibility is said to reside. Another would be that it could conserve the information needed from time to time for the deep renewals of renaissance. The added element is that 10,000 years is an extremely long view, during which time there are likely to be profound cataclysms requiring many-levelled renewal. Building real value into a 10,000-year library could be an intellectual adventure as challenging as space travel.

You can read more about it here, here, and here. It’s a remarkably ambitious project in that, historically speaking, libraries are fragile things, susceptible to every kind of degradation. The Library of Alexandria might have been Greek Big Data, but most of that data is long lost.

One strange conceit of the program? They’re hoping to limit the Manual to about 3,500 books. That seems wildly under-representative of the knowledge required to jumpstart civilization after a cataclysm or two; those 3,500 volumes better be bangers.

¶ Greatest economist of all time? The abovementioned Tyler Cowen has written some pretty stellar books, but none more noteworthily published than his latest, GOAT: Who Is the Greatest Economist of all Time and Why Does It Matter? He’s made the entire book available for free download in several different formats. But what’s special is the book boasts an interactive AI feature.

In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates complains that if you ask a book a question, it can only give you the same answer again and again. Not anymore! “You can ask it to summarize, ask it for more context, ask for a multiple choice exam on the contents, make an illustrated book out of a chapter, or ask it where I am totally wrong in my views,” says Cowen.

Whether you care about economics or whom among its practitioners might be the best, it’s worth playing around with. Henry Oliver discusses the book and his exchanges here. I played around with it last night and thought some of the responses were very useful.

One negative: The digital-only publication and the AI feature ties you a digital device—your phone, laptop, or whatever—a vastly different experience from picking up a paperback book.

¶ Formats matter. Author Isaac Fitzgerald sings the praises of paperbacks. While his impoverished parents painstakingly curated a library of hardback books, carefully moving their valued collection from house to house, their son fell in love with cheaper, more disposable fare:

When I read a paperback book, it’s like I’m wrestling with it. Soon the cover is torn and the pages are dog-eared and there’s a giant seam down the middle where I folded the book in half [wince!—JJM] so I can stuff it into my back pocket, or jacket pocket, or perhaps a friend’s mailbox. . . . A paperback is built for adventure.

I do love a paperback for convenience and portability. Of course, for pure portability it’s hard to beat digital and audiobooks, which fit by the thousands on a device already in your pocket. But like Cowen’s AI book, every format presents tradeoffs.

I’m a big fan of audiobooks, and have written glowingly about their benefits here. I’ve also looked at the tradeoffs here. Researchers Janet Geipel and Boaz Keysar penned one of the studies I covered. Here they are talking about how the difference in format—reading vs. listening—affects our cognitive processes. The upshot? Visual reading facilitates more critical engagement than listening. “If you’re considering a controversial topic,” they say,

and a relatively deliberate, analytic judgment or decision would be valuable, you may want to read about it, assuming that’s an option. But for matters of the heart, about which you would prefer to let your intuition and feelings reign, listening might be all you need.

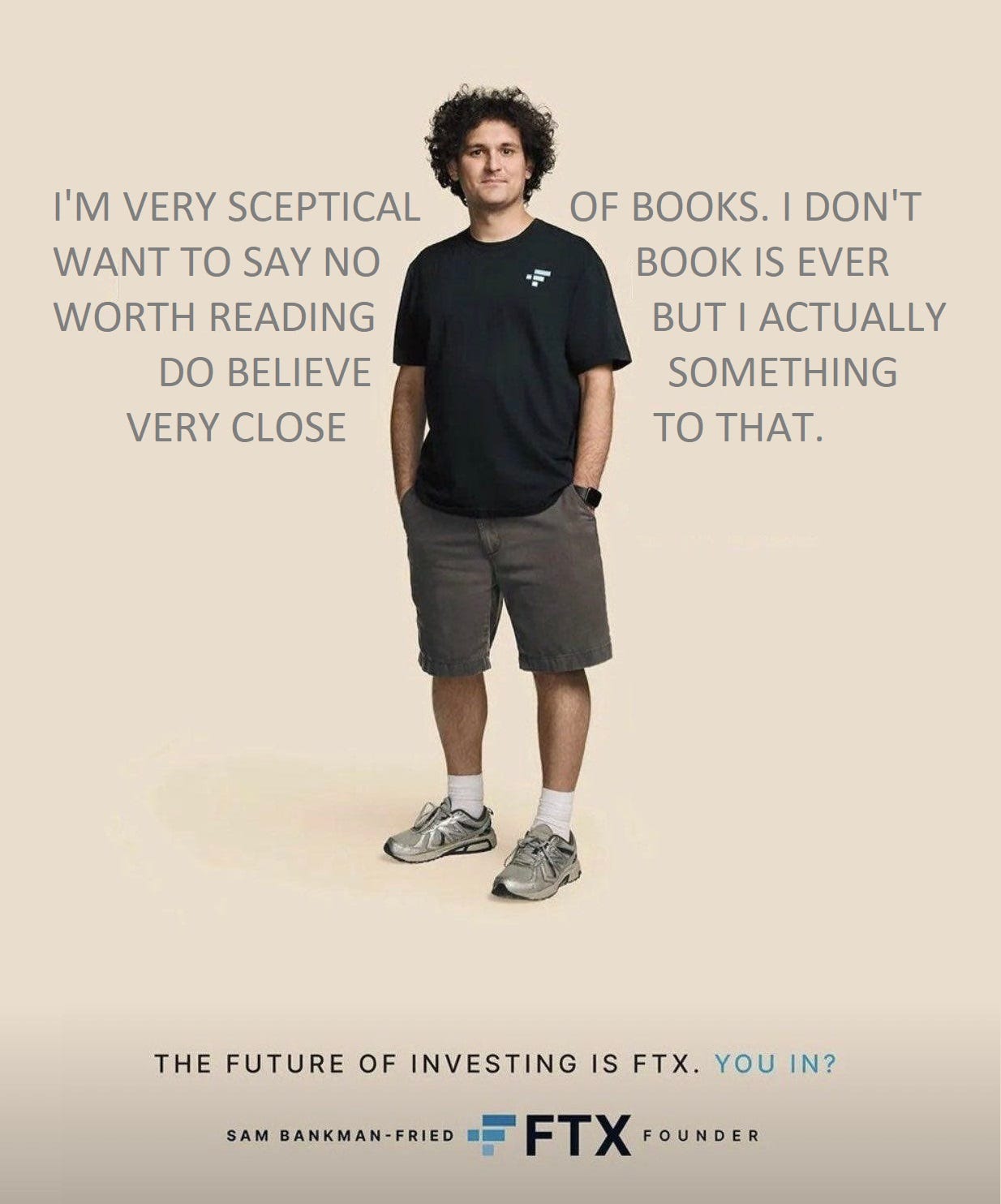

¶ SBF, reverse poster boy for English majors. We’re not a truly meritocratic society; all that matters is the appearance. As Tonio K. sang, “The facts don’t matter, just the feel.” Before the downfall of Sam Bankman-Fried, who founded the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange before the whole enterprise melted down and he was convicted of fraud, people would regularly point to him as some sort of sage.

One of his more counterintuitive oracular pronouncements: “I’m very skeptical of books. I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that.” Analyzing the SBF story, David Streitfeld commented,

It’s impossible to read the sad saga of Mr. Bankman-Fried without thinking he, and many of those around him, would have been better off if they had spent less time at math camp and more time in English class. Sometimes in books, the characters find their moral compass; in the best books, the reader does, too.

Stewart Brand’s a reader. So was Steve Jobs. SBF could have learned something from their example. Instead, his story stands as an accidental defense of the humanities—reverse poster boy for the real value of an English degree.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please punch the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

What an interesting post! I had no idea The Whole Earth Catalog was so influential.

One of my favorite living authors, Neal Stephenson, is involved in the Long Now Project, I think. He's also encouraging contemporary sci-fi authors to write more optimistic stories instead of all the dystopian ones publishers are currently churning out. He says that if we don't give young adult readers stories that inspire hope and innovation, we are hurting ourselves and our future. Makes sense to me.

Another fan of paperback books here. Their cheapness means I can take one to work and drop it in the mud or get egg salad stains all over it and that's okay. But "cheap" in this case doesn't need to mean "low quality"; a paperback with a sewn binding is of the same durability as a hardbound book and won't fall apart like perfect bound paperbacks are always doing.