All the Horrifying Things We Do to Our Books

How Much Damage Can You Do to a Book and Still Live with Yourself?

When author Norman Mailer gave J. Michael Lennon his book Advertisements for Myself, the copy was missing more than a hundred pages. Mailer had yanked out entire chunks. “For Mike, this working copy of Advertisements for Myself with sections removed,” Mailer inscribed the book. “God knows what I tore them out for.” It was a first edition.

“Mailer couldn’t live without books,” said Lennon, his biographer. Indeed, Mailer’s library boasted more than seven thousand volumes. But plenty of those bore signs of violence and disfigurement. “Books cringed when they felt his hand,” said Lennon.

When he needed some pages for a public reading, he often tore them out of the book rather than carry it. . . . His copy of Priscilla Johnson McMillan’s Lee and Marina (1977), dismembered when he went to Dallas with Larry Schiller to interview Marina Oswald, was later patched together with duct tape. Dostoevsky’s The Idiot was similarly reconstructed. One of his favourites for public readings was a six-page description of an embalming from the opening chapter of Ancient Evenings (1983). Norris [Church, one of Mailer’s wives] was furious when he ripped this section from her inscribed copy, and then lost it.

Too late for a trigger warning?

How could someone like Mailer who made his life on words—particularly books—treat them so poorly? “He was not interested in them as objects,” explained Lennon, simply. And it raises an interesting question: What, if anything, do we owe our books in terms of care and respect?

Longstanding Concern

The standard abuses are well known and have been catalogued for ages. “Never allow looks to be near damp . . . for they mildew very soon,” warned Luke Limner in a preachy 1852 listicle. Ah, but neither should you overcorrect! “Never permit,” he added, “books to be very long in a warm, dry place, as they decay in time from that cause.”

Most of the sins Limner enumerated do obvious physical damage to the form of books, their shape and components. Some further examples:

“Never, in reading, fold down the corners of the leaves, or wet your fingers; but pass the forefinger of the right band from the top of the page to the bottom in turning over.”

“Never permit foreign substances, as crumbs, snuff, &c., to intrude into the backs of your books; nor make them a receptacle for botanical specimens, cards, or a spectacle case, as it is like to injure them.”

“Never leave a book face downwards, on pretext of keeping the place; for if it continue long in that position, it will ever after be disposed to open at the same page, whether you desire it or not.”

”Never stand a book long on the fore-edge, or the beautiful bevel at the front may sink in.”

“Never wrench a book open, if the back be stiff, or the edges will resemble steps ever after; but open it gently, a few pages at a time.”

”Never pull books out of the shelves by the headbands, nor toast them over the fire, or sit upon them. . . .”

You get the feeling he was having some fun at the end. I’ve never toasted a book over a fire, but I have temporarily stored books on their fore-edge. Limner was right about that: Not only did the bevel at the front sink in on a few larger books, but the spine—ack!—went slightly concave. I was mortified when I removed them from the box.

Still, these faux pas would seem to pale in comparison to those mentioned in Richard de Bury’s medieval guide, Philobiblion, where he decried,

some headstrong youth lazily lounging over his studies, and when the winter’s frost is sharp, his nose running from the nipping cold drips down; nor does he think of wiping it with his pocket-handkerchief until he has bedewed the book before him with the ugly moisture. . . . He does not fear to eat fruit or cheese over an open book, or carelessly to carry a cup to and from his mouth; and because he has no wallet at hand he drops into books the fragments that are left.

Snot and cheese? Lord, have mercy.

Whose Standards?

More recently, when Penguin UK asked readers what horrifying things people do to books, most of the answers were predictable: cracking the spine, dog earring the pages, underlining and highlighting, writing in the book, leaving in the sun, and so on.

I hadn’t considered a few of the suggestions, such as reading with sticky fingers (nasty), but some of these supposed crimes are beloved practices for me. No, I never use bacon rashers as bookmarks (something de Bury would also abhor), but I do write in my books all the time. I’ve also stained more than a few with coffee. Can’t seem to help it. One person’s atrocity is another’s attraction.

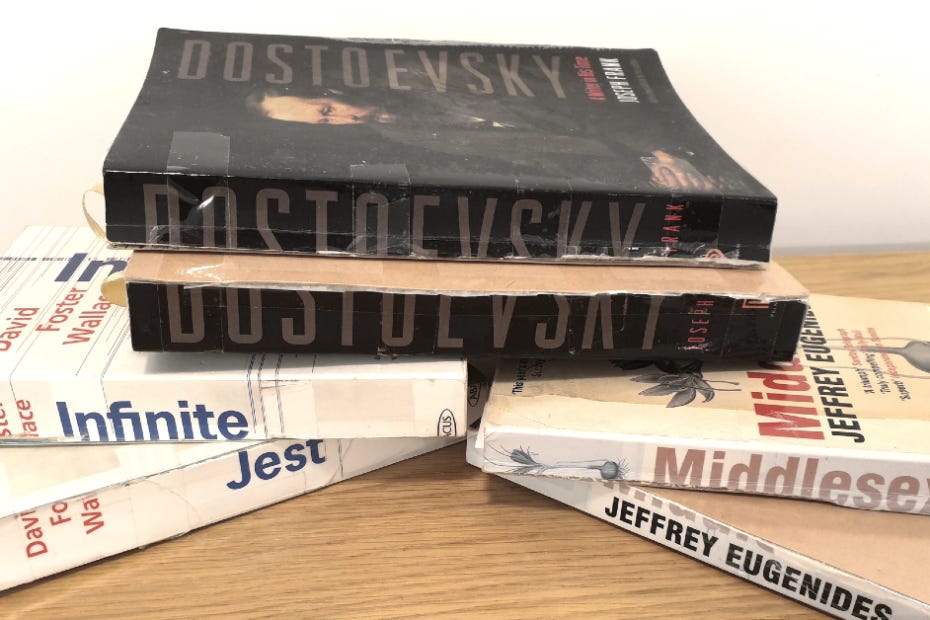

When Alex Christofi admitted he cut overlong books in half “to make them more portable,” a colleague called him a “book murderer.” Christofi came clean on Twitter with an image of his handiwork—Infinite Jest, Middlesex, and a hulking Dostoevsky biography split right down the middle.

Aghast, the whole angry world piled on. Christofi’s post garnered tens of thousands of retweets, several times as many likes, and plenty of outrage before he eventually deleted it. Maybe he should have known better. Christofi is, after all, a professional editor; he works for a publishing house. What’s more, he’s written several books of his own.

But then again, doesn’t that personal history speak in his defense? It’s not as if Christofi has no love for books. If such affections could be measured, I bet he actually cherishes them more than many of his detractors. Besides, just how wrong is slicing books in two?

Consider Christofi’s job. When I was a professional book editor, I regularly cut books down to size. I once told a writer that we were going to have to prune his 200,000–word manuscript down to 100,000 words. I was in Nashville at a desk; he was in Manhattan on the sidewalk. “I’m going to throw this effing phone across the street,” he said when I gave him the news. In the end he apologized for his language, and I let him keep his words. Mostly, however, I cut when necessary.

When I first started in the editorial business, I asked a senior editor about cutting a paragraph. I was hesitant. Didn’t it violate the Hippocratic oath or something? “You’re the editor,” he said. Of course you should cut it, he was saying, somewhat irked he had to tell me. In his defense, he was on deadline and I was interrupting. Regardless, the lesson stuck.

Nip, tuck, delete. That’s what editors do: We prepare the work of authors for the benefit of readers; it would seem that’s all Christofi did—just after the fact, and with himself as the only reader in view.

So why is Christofi the editor immune from the vitriol dished upon Christofi the reader? Theoretically, authors have a say in how their books are edited (we do use Track Changes). But not always, and the publisher usually has the contractual right to not only edit the book however they desire, but also prepare it for publication most any way they choose.

And this has implications for how we treat all sorts of literature. Oxford book history prof Adam Smyth recently shared a video of himself slicing—gasp!—his copy of Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa down the middle with a bread knife. The Penguin edition of the eighteenth-century novel is gargantuan—1,534 pages in all. But originally, the book was published serially, and later in multivolume sets. The murder-your-grandmother-with-a-single-volume monstrosity is a modern invention that has nothing to do with Richardson’s original intent. In fact, as Smyth points out, the novel is epistolary; it practically wants to be divvied up into smaller pieces. If you squint at it just right, Smyth’s bibliocidal violence seems corrective, even restorative.

What makes a book more sacred once it’s printed than before it leaves the author’s outbox? And are we retroactively canonizing the decisions of later editors and publishers? Maybe we’re sanctifying the work of the printers and pressmen. Prior to publication, a book is only clay fit for molding. Afterward, it’s a sacred object, a relic.

New Holy Book?

It’s at least curious, no? A secular age such as ours mocks the pious and sports with the sacred. We have no holy book—except the elevated form of the $17.99 paperback! Like the Torah it stands untouched. Like the Quran it dares its molesters: “Deface me at your own risk!”

Am I now defending the desecration of books? No, though I am making a gentle plea for less dogmatism about their care. I hate the mishandling of my books. But I also recognize not all the books out there are mine, and their owners have their own standards. Someone else might have different concerns. In fact, based on the variable responses of informal polling such as Penguin UK’s, we know they do.

I, for instance, love a dust jacket. When I see someone tear theirs off a new purchase and deposit it in the trash, I wince inside. If I’m honest, I entertain uncharitable thoughts. But I also recognize benighted barbarians are free to dispose of dust jackets if they choose. I try not to hold it against them, but I also think twice before I loan one of my own—and by think twice I mean I never let the book out of my sight without an RFID tracker, a copy of the borrower’s drivers license, and a blood sample.

I bet we also recognize that damaging a book can sometimes testify to our affection. Think of that ragtag copy of Augustine’s Confessions or Rilke’s Letters, the one that’s been in and out of your backpack for a decade. The deplorable condition of a book sometimes bears the record of our symbiosis with it.

More than once at church I’ve noticed a priest or deacon intoning the liturgy from a threadbare old service book with the visible glint of packing tape down the spine. It doesn’t make me cringe; it makes me smile. Similarly, I can recall sitting in an outdoor church service in Uganda and seeing a woman with a tattered, coverless Bible missing the opening pages of Genesis and the final pages of Revelation. She probably loved that book more than anything.

I’m not suggesting we shred and destroy. And by all means, if you’re a collector, collect. I have significant respect for people that build large libraries of immaculate and well cared for books. But we needn’t be puritanical. Caesar divided Gaul. Christofi divided Middlesex. Who’s the real tyrant?

Mailer’s mangled library reminds us that books are meant to be used more than worshipped, and we should be reticent about imposing our standards on others—or at least demonstrate enough generosity to recognize other standards exist.

That said . . . step away from my dust jackets.

What about you? Cracked spines, water damage, folded pages—let us know what horrifies you most about the treatment of books. Share it in the comments below.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post—or hated it!—please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I've used a book as a murder weapon. A gross beetle suddenly appeared on my dining room floor and in my panic I grabbed the giant Mapp & Lucia omnibus (written EF Benson in the 1930's-- the books are hilarious) and dropped it on the bug

The crime scene remained untouched for a week before I got up the nerve to pick it up.

Books as aesthetic kind of goes against the point. I don't see them as precious objects, and wear and tear according to the owner doesn't bother me at all.

Great essay. I was quite entertained.