Bookish Diversions: Kafka’s Tricksy Translation

Innocent Mistake, Kafkaesque, Tricksy Bits, What Bugs Translators, Interfering Moustache, More

¶ Innocent mistake. Franz Kafka’s The Trial introduces its protagonist as an unlucky man, arrested without cause and tormented by an arbitrary, unjust legal system. “Somebody must have made a false accusation against Josef K.,” runs the opening line in Idris Parry’s translation, “for he was arrested one morning without having done anything wrong.”

K.’s innocence? In this and every English version, it’s a given. Little wonder we so easily label thoughtless bureaucratic travesties Kafkaesque—or that, as Ohio State professor Paul Reitter points out, hundreds of judicial opinions in American courts cite Kafka along those lines. We resort to it all the time. “‘Kafkaesque,’ in multiple languages,” says Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski, “shows up regularly in newspapers to describe the experience of immigrants awaiting entry, the accused awaiting trial, the innocent imprisoned, and anyone dealing with bureaucracy.”

But what if we’ve fallen into the innocent-suffering-injustice thing by mistake?

The original German doesn’t presume K.’s innocence, not according to Reitter. “The subjunctive form,” he says, “signals, unobtrusively but importantly, that we don’t have here an unambiguous statement of fact.” German introduces an “element of uncertainty” that English can’t readily replicate. Instead, Kafka starts with something squishier: Maybe K. is innocent, maybe he isn’t. While his Anglophone translators push us toward one reading, Kafka’s language keeps both possibilities alive.

Significantly, this is far from the only instance in which Kafka’s language sets traps for translators.

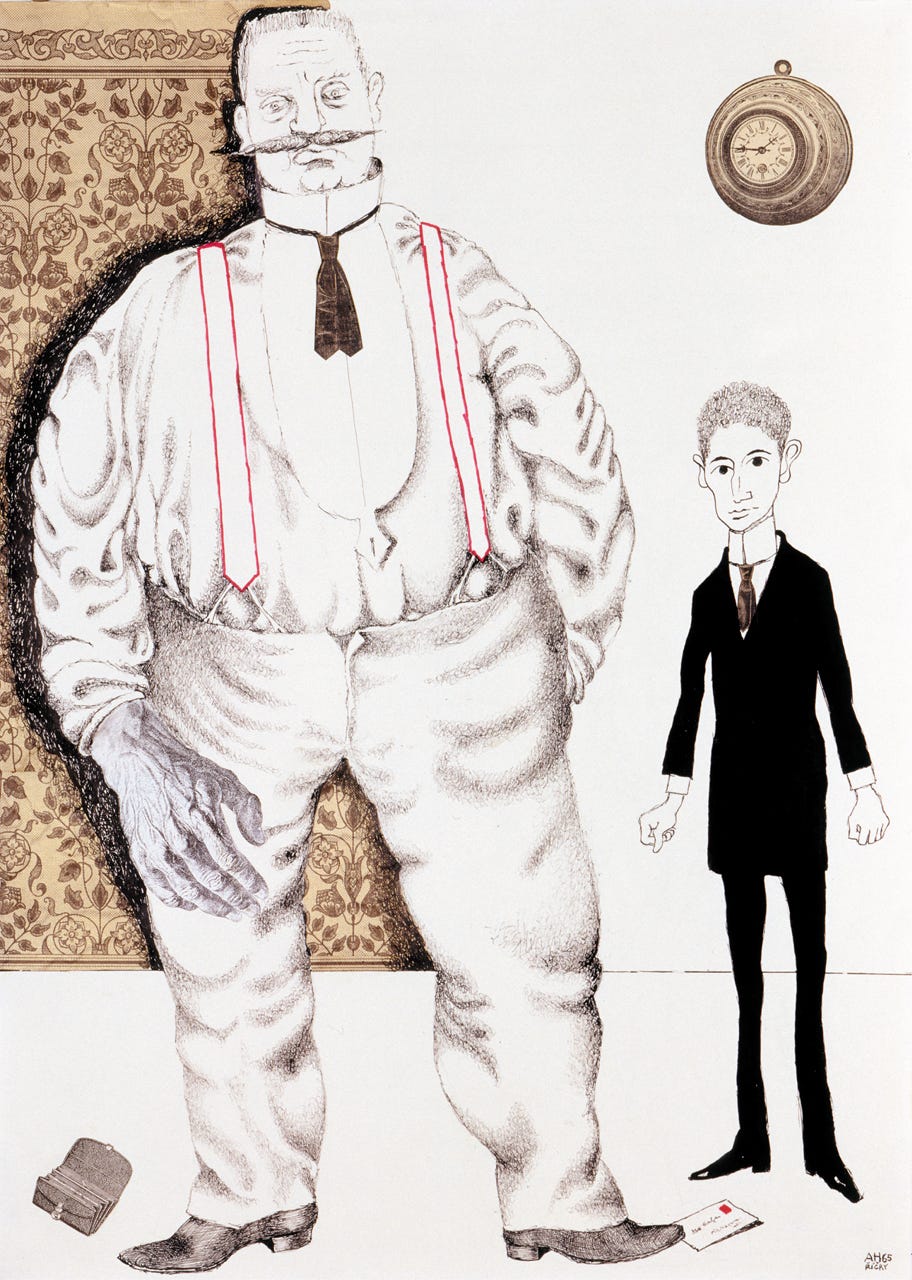

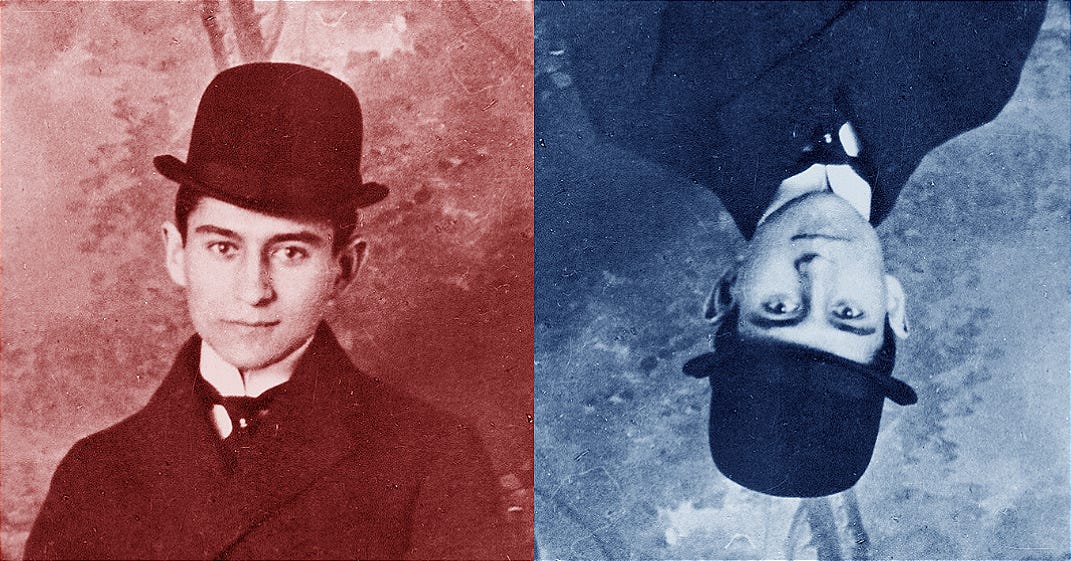

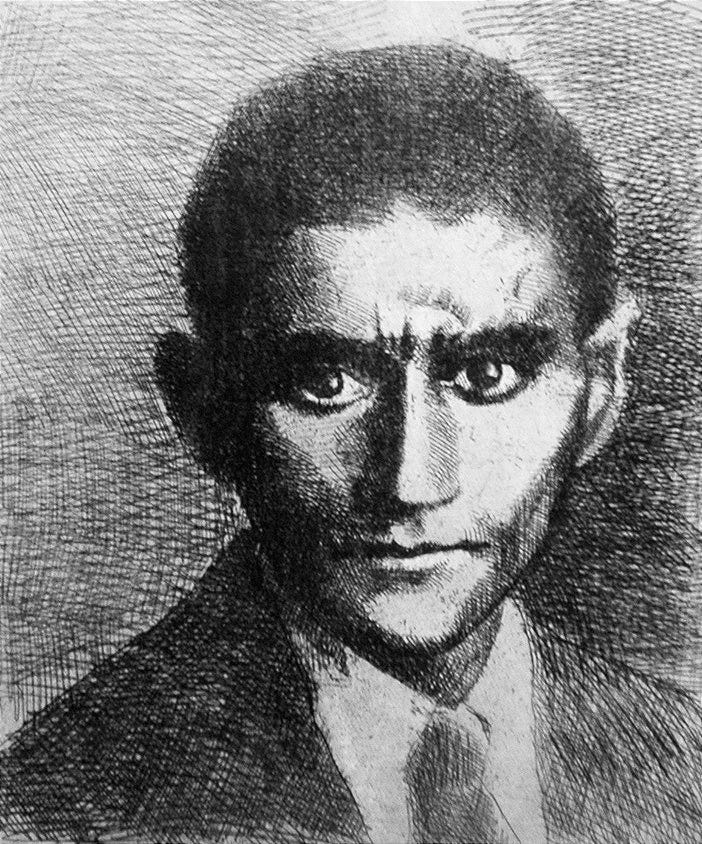

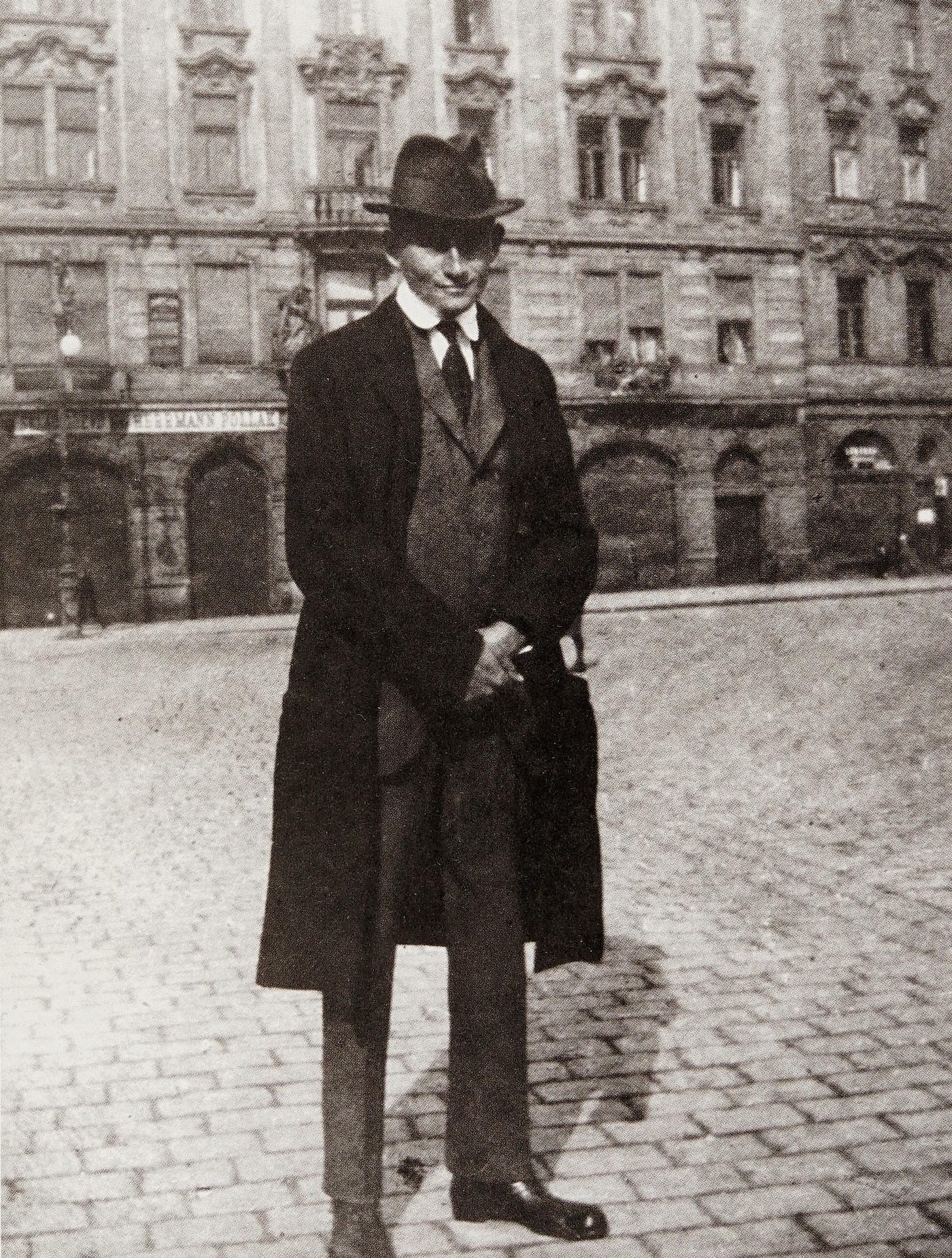

¶ Prophet for our times. Born in 1883, dead by 1924, Kafka missed three quarters of the last century and the first quarter of this one. Yet few writers have so effectively addressed the subterranean frustrations and fears of modern life. “Kafkaesque,” says biographer Frederick R. Karl, is “the one word that tells us what we are, what we can expect, how the world works.” It applies, he says,

when you enter a surreal world in which all your control patterns, all your plans, the whole way in which you have configured your own behavior, begins to fall to pieces, when you find yourself against a force that does not lend itself to the way you perceive the world.

You don’t give up, you don’t lie down and die. What you do is struggle against this with all of your equipment, with whatever you have. But of course you don’t stand a chance.

Who hasn’t felt like that from time to time? For any author who might channel or explain such anxieties, it would seem criminal to lock him behind his native language. But Kafka’s linguistic immigration has always proven—as our presumed innocent problem demonstrates—somewhat Kafkaesque on its own.

¶ Tricksy bits. Kafka is notoriously difficult to translate. Says Rebecca Schuman, “[Kafka’s] word choices and style fight even their original language, much less attempts at bringing them into ours.”

“We know before we start—and with Kafka, I think, especially after we’ve finished—that we’re not going to get it right,” says one of his translators, Joyce Crick. “On the other hand,” she adds, “we will persist in doing it.” (I’m reminded of Chesterton’s line: “If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.”)

In his native German Kafka leaves an understated style on the page. Translator Mark Harman says creating the same effect in English “is at least partly foredoomed.” Why? Several difficulties present themselves, starting with syntax; Kafka loves what for English readers would be uncomfortably long sentences. Schuman mentions one instance—a single sentence with 64 words. An English translator could easily split that sucker up into two or even four sentences; instead, Kafka tosses in a handful of commas and lets readers fend for themselves.

Kafka also likes to play with point of view in confusing ways, says Harman, referring to “Kafka’s blurring of the line between the perspective of the generally unobtrusive narrator and that of the main character. . . . Even within the same sentence Kafka can switch back and forth. . . .”

These aren’t all. Kafka sometimes jumps between verb tenses in baffling ways and also dots his sentences with little words Harman calls “flavoring particles.” These

carry a range of possible meanings, such as wohl (perhaps, probably, indeed) and doch (however, but, indeed, after all). Whereas careless writers of German sprinkle such words into their writing with abandon, Kafka deploys them with characteristic precision and so the translator needs to figure out from the context which of the multiple meanings of those little words makes the most sense.

Translator Michael Hofmann complains about these same “particles” as well. From his introduction to Metamorphosis and Other Stories:

wenn, aber, da, nun, doch, auch—the little words, not much used in English . . . that change or reinforce the course of arguments in his prose. . . . You have to be very careful not to produce a wash of needless and directionless verbiage in English that has the opposite effect to the drily controlling one Kafka intended. . . . It is a hard thing to do what I’ve had to do . . . to translate with an author and against a language.

With an author, against a language? Tricksy, indeed.

Talking with Will Self, Joyce Crick explains one of the difficulties—back to the subjunctive issue we started with. In English a point collapses into a fact, whereas Crick says Kafka’s world is more speculative. The trouble is that English effaces those subtitles. As a result, says Crick, “Don’t expect the real thing.”

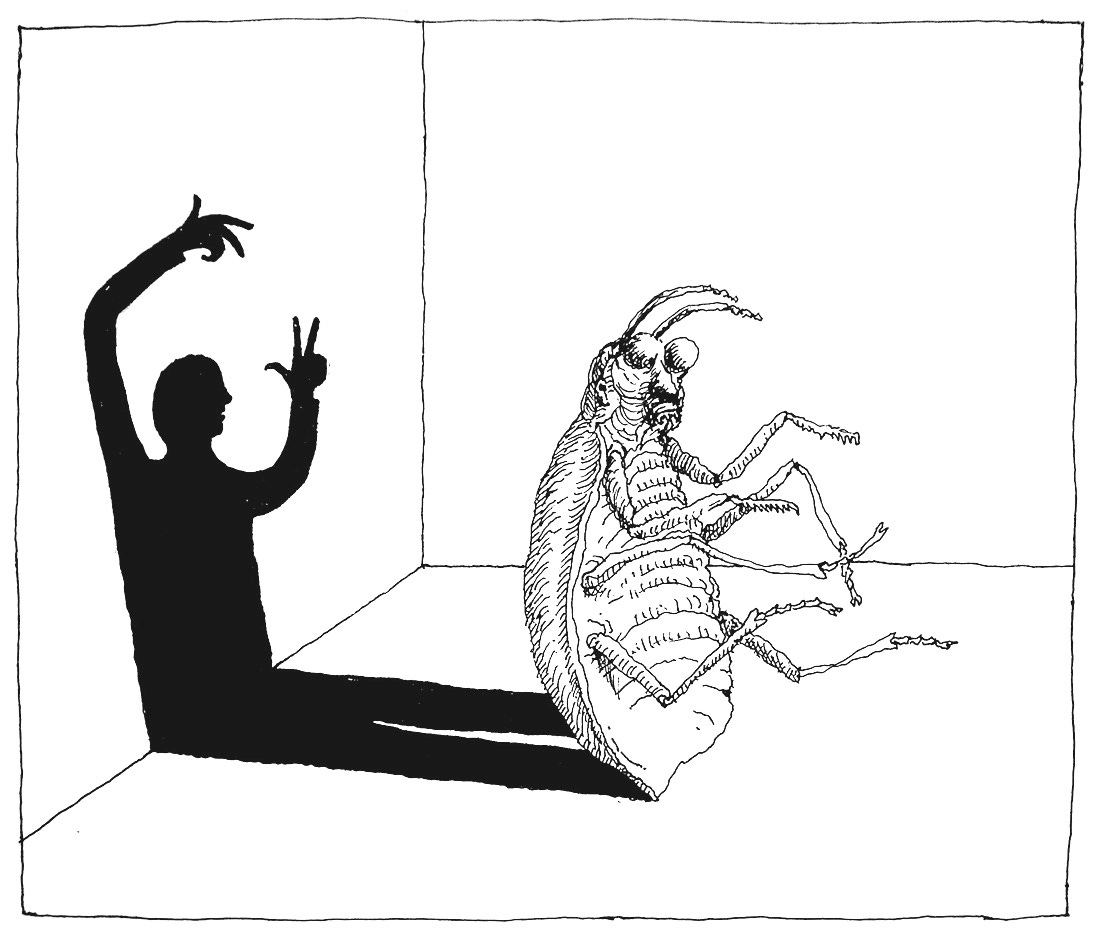

¶ What bugs translators? Even the simple isn’t so simple. The Metamorphosis is even more famous than The Trial, and yet its opening line is every bit as problematic. The story is well enough known. Gregor Samsa wakes to find himself transformed into a giant . . . what, exactly? Here are six different translators taking a swing at the sentence.

Susan Bernofsky: “When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed right there in his bed into some sort of monstrous insect.”

Joyce Crick: “As Gregor Samsa woke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed into some kind of monstrous vermin.”

Michael Hofmann: “When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself changed into a monstrous cockroach in his bed.”

Christopher Moncrieff: “One morning, as Gregor Samsa woke from a fitful, dream-filled sleep, he found that he had changed into an enormous bedbug.”

Edwin and Willa Muir: “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

John R. Williams: “One morning Gregor Samsa woke in his bed from uneasy dreams and found he had turned into a large verminous insect.”

Quite the selection: Monstrous insect, monstrous vermin, monstrous cockroach, enormous bedbug, gigantic insect, verminous insect. Kafka gave us ungeheueres Ungeziefer but, as Bernofsky points out, his phrase resists translation.

Both the adjective ungeheuer (meaning “monstrous” or “huge”) and the noun Ungeziefer are negations—virtual nonentities—prefixed by un. Ungeziefer comes from the Middle High German ungezibere, a negation of the Old High German zebar (related to the Old English ti’ber), meaning “sacrifice” or “sacrificial animal.” An ungezibere, then, is an unclean animal unfit for sacrifice, and Ungeziefer describes the class of nasty creepy-crawly things. The word in German suggests primarily six-legged critters, though it otherwise resembles the English word “vermin” (which refers primarily to rodents). Ungeziefer is also used informally as the equivalent of “bug,” though the connotation is “dirty, nasty bug”—you wouldn’t apply the word to cute, helpful creatures like ladybugs.

Here she explains her own choice:

In my translation, Gregor is transformed into “some sort of monstrous insect” with “some sort of” added to blur the borders of the somewhat too specific “insect”; I think Kafka wanted us to see Gregor’s new body and condition with the same hazy focus with which Gregor himself discovers them.

Makes sense. But so do the others. Hofmann goes with “monstrous cockroach,” a choice with which Schuman says she vehemently disagrees. Who’s right? As you know, I’m inclined to say that’s an unhelpful—and mostly unanswerable—question.

¶ The interfering moustache. Kafka would probably laugh about the whole issue. In fact, he did. In The Trial, he plays untranslatability for a joke. In one later scene, K.’s supposed to translate for an Italian, a man with a “dark, bushy moustache speckled with grey,” as Mike Mitchell’s translation has it.

But K. can’t follow the fellow. He speaks too fast and keeps slipping into a dialect K. finds impenetrable. The joke? It’s in that lip warmer. If only K. could read his lips. Alas, the moustache is too big! “His moustache concealed his lip movements, which might have helped K. understand.” Figures. The only way out of the mess is blocked by ambitious facial hair.

¶ Many Kafkas. One way out of the conundrum is get comfortable with Joyce Crick’s statement: “Don’t expect the real thing.” We can take that as discouragement, or we can seize it as license. As Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski says about two dueling translations, “Both books are valuable in bringing us somewhat different Kafkas.” All translations do so, and most of those on the market do it rather well.

We don’t need the real thing to have a good thing. Paul Reitter compares Bernofsky and Harman’s version of The Metamorphosis. Despite what he regards as their drawbacks, “both renderings are excellent: careful, thoughtful, and polished. They give us a Kafka who is recognizably himself. In fact, for an author so much associated with radical singularity, linguistic self-alienation, and Talmudic indeterminacy, or, in a word, untranslatability, Kafka has proven to be remarkably translatable.”

That’s a relief.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon, share it with a friend, and 💬 discuss it in the comments below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

While you’re here, make sure to tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, and discover the preorder bonuses!

This was wonderful; thank you!

I want to like Kafka so much. I like what I have read *about* him. I am a quarter Czech. I love that according to Kundera, Kafka means "jackdaw" as in the bird, and I have fairly close ancestors named Kafka although they were not Jewish. I listened years ago to a History of Literature podcast episode about the worst/best night of his life and the famous letter to his father and think about it regularly. One of our top twenty children's books is Kafka and the Doll and my daughter dressed up as him when she was six for literature day at school. I love the tone and attitude of the quotes and pieces of his work that regularly come across the transom of my bookish Substack experience. We have all the ingredients for being a Kafka household, people.

But what we don't have is an ability on my part to grapple successfully with his *books*. I've been grimly trying to get through The Castle for ages. The long sentences; the long paragraphs; the inscrutability of the characters and their actions and motivations; the hitting-walls-in-mazes feel every time a tiny bit of plot momentum gets going. I know that's all purposeful. But it's hard! It's interesting to know that part of the challenge is the translation issues which were apparently also purposeful. Our boy Franz deserves a noogie for making the puzzles so hard!

I love how translations are so different. I recently heard Daniel Mendelson talk about translating the Odyssey and how he handled the many epithets. Translation is a never a straight line and capturing the sense of the meaning is more of an art than most people realize.