George Orwell: Terrific Writer, Terrible Husband

Do We Cancel? Reviewing ‘Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell's Invisible Life’ by Anna Funder

When I picture an author, I usually imagine a person working alone. Though a book “often strikes back at society,” as Jerzy Kosinski said in his 1969 National Book Award acceptance speech, it “is born in privacy.” Such a portrait conjures the myth of the independent creator, fashioning words in the smithy of solitude before presenting them to an awaiting public.

But that’s not how it works, is it? Like all of us, authors are embedded in communities and relationships. Can we really say a book is born in privacy when someone reads over the author’s shoulder? And what if the onlooker contributes more than a glance?

Such is the case of George Orwell’s first wife, Eileen Blair née O’Shaughnessy, the elusive subject of Anna Funder’s biography, Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life. For the nine years of their marriage, as Funder demonstrates, Eileen’s efforts made Orwell’s life and work possible.

Not that most of us would know it. In 1938 Alfred Hitchcock directed The Lady Vanishes. After marrying Orwell two years before, in 1936, Eileen began living her own version of the tale and has only begun to reappear in any significant way in the last few years.

Unacknowledged Collaborator

The couple met at a friend’s house, the lanky Orwell talking with a friend by the fireplace, smoking cigarettes. He took an immediate liking to Eileen. His intellectual equal, she had studied at Oxford and was working toward a degree in psychology at University College London and possibly a writing career of her own. Though their marriage ended that dream, she became Orwell’s first reader, critic, and editor.

Orwell would spend hours writing each day and then give his pages to Eileen to type. But more than reproduce his words, she would critique and edit them as well, arguing a point, correcting an expression. His biographers admit Orwell’s writing improved after marrying, but they avoid supplying a name for the cause. Yet in some cases Eileen’s contribution proved fundamental to the work.

Determined to make a public statement on the scourge of Stalinism, Orwell decided to write a banger of an essay on the subject. An essay? Eileen suggested something more engaging, more captivating. While at Oxford she studied fables under J.R.R. Tolkien. What about a parable, a story that could stand up on its own but which would likewise illuminate the issues in question?

Orwell later admitted Eileen had a hand in “planning” Animal Farm, but her contribution was more extensive. Not only did she suggest the very form of the story, but the two discussed the book each day, staying up at night and talking over the tale in bed.

The effect of her influence is clear from the final product. C.S. Lewis much preferred Animal Farm to 1984. Regarding the latter, he said, “It seems to me . . . to be merely a flawed, interesting book; but the Farm is a work of genius which may well outlive the particular and (let us hope) temporary conditions that provoked it.” And it wasn’t just Lewis.

Funder notes that Orwell’s own friends recognized the book as something special. Richard Rees, who knew him for decades, could hardly fathom how he found “a new vein of fantasy, humor, and tenderness.” Compared to Orwell’s usual “grey novels,” publisher Fred Warburg said there were few hints “he was capable of this supreme effort.” Eileen’s friends were certain of her influence. “I have little doubt,” said Lydia Jackson, “that in a subtle, indirect way Eileen had collaborated in the creation of Animal Farm.”

To this day Animal Farm is regarded as a triumph. Translated into more than seventy languages, it’s still read, studied, and cherished around the world. It subtracts nothing from Orwell’s accomplishment to admit the help of his wife—no more than it diminishes Tolkien or Lewis to recall the influence of the Inklings on their unfolding drafts. If a book is born in privacy, it’s only partially so.

Male-Pattern Blindness

What’s fascinating about Funder’s reconstruction of Eileen’s life is the effort required to place her in Orwell’s story. She was there for almost a decade in the thick of the action but overlooked and sometimes actively effaced.

Eileen’s friends left recollections, and she wrote several letters that can be corroborated with moments in their marriage. But to sketch a complete picture Funder was forced to go beyond the archival materials and weave fictionalized scenes between the more factually certain episodes. I’m mixed as to the effectiveness of this method, but I understand her decision.

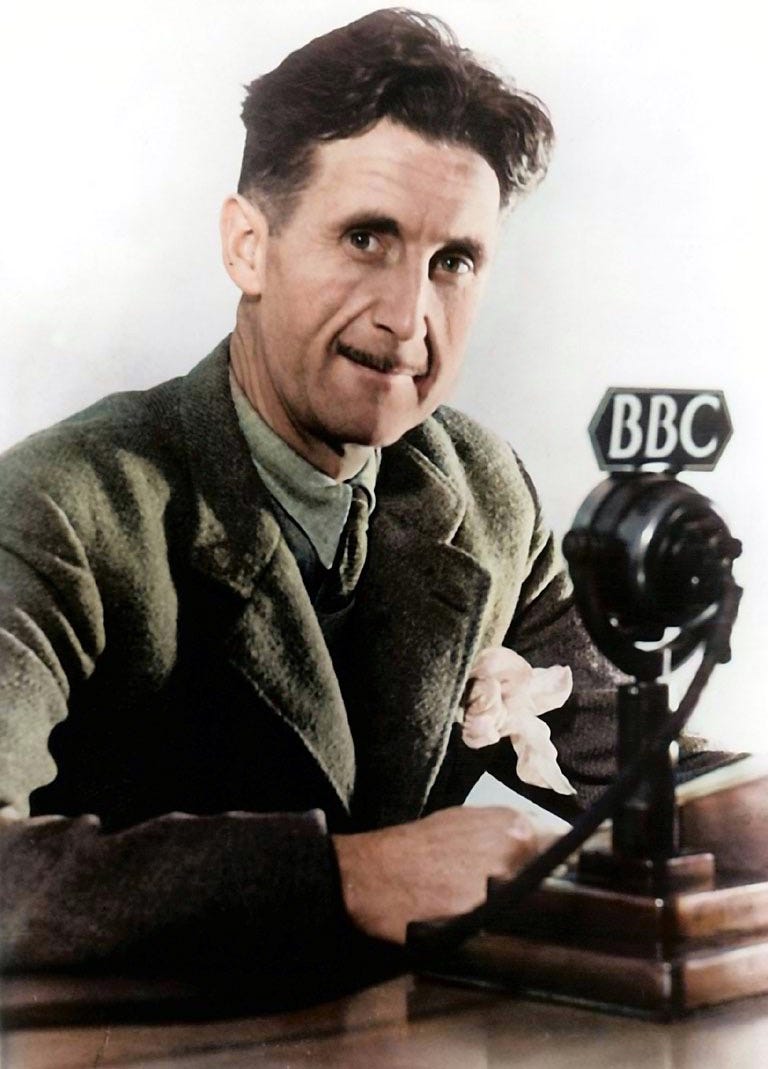

Few of Orwell’s biographers give Eileen much attention, and even Orwell seems to have kept her memory vague—whether intentionally or as the result of some sort of male-pattern blindness is hard to say. Consider their time in Spain.

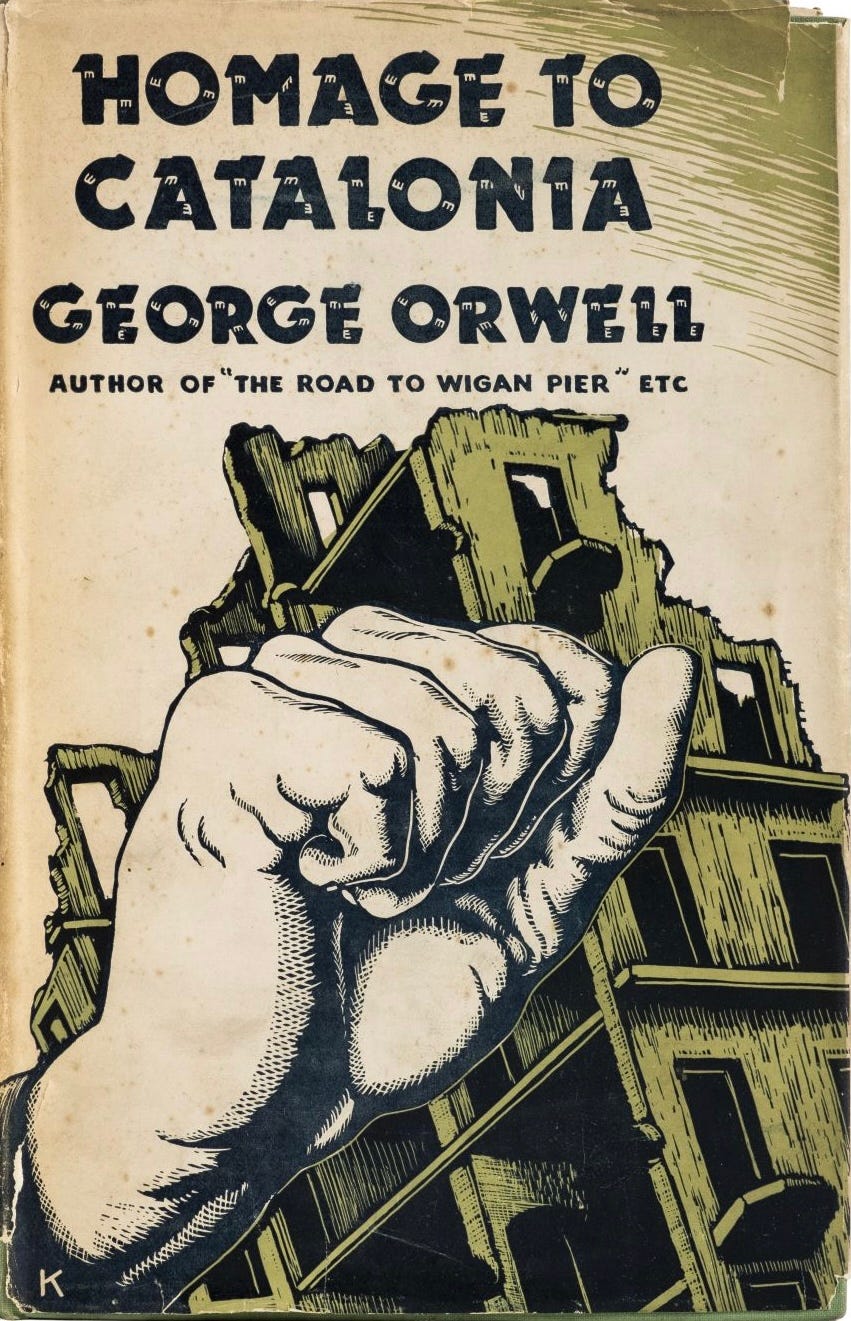

Shortly after they were married, Orwell announced he was traveling to Spain to fight fascists in the civil war. Orwell joined the Independent Labour Party, an anti-Stalinist British communist organization in Barcelona. Thanks to the ILP’s relationship to the POUM—Partit Obrer d’Unificació Marxista, or Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification—Orwell had a ticket to the front both to fight and to write about the action, the original gonzo journalist. He even got shot in the neck.

Orwell captured his adventures in Homage to Catalonia. Missing from his account? Though he referenced his wife thirty-seven times, Eileen’s name never bubbles to the surface in the book; she’s simply “my wife.” Nor did he describe the majority of her activities, which were substantial and even essential for their nick-of-time escape from the country.

Shortly after Orwell arrived in Spain, Eileen decided to follow him. She joined the ILP’s office in Barcelona and began working for their print and radio propaganda effort. She was at the center of activity, coordinating communication, provisioning soldiers, enduring police raids and Soviet spies.

While POUM operatives were rounded up and jailed, Eileen was forced to keep her cool and stash incriminating documents. While the entire operation existed under surveillance, Eileen faced the same police who had searched her rooms to secure passport stamps so she and Orwell could leave the country.

Orwell mentions getting the passport stamps—but not that Eileen did it. He doesn’t even mention her work with ILP. It’s as if it all happened by magic. Meanwhile, the Soviets were under no illusions about Eileen’s direct involvement. As the two fled Spain, Stalinist operatives were ordered to bring them in; an arrest warrant not only labels them “rabid Trotskyites,” it mentions them both by name.

Says Funder,

Eileen had worked at the political headquarters, visited him at the front, cared for him when wounded, saved Orwell’s manuscript . . . saved the passports, saved Orwell from almost certain arrest at the hotel, and somehow got the visas to save them all. How is it that she remains invisible?

Grammar offers one answer. Both Orwell and his biographers employed the passive voice. “Manuscripts are typed without typists, idyllic circumstances exist without creators, an escape from Stalinist pursuers is achieved,” says Funder. “Every time I saw ‘it was arranged that’ or ‘nobody was hurt’ I became sensitised—who arranged it? Who might have been hurt?”

Ironically, Orwell himself inveighed against passive voice. “Never use the passive where you can use the active,” he chided in his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language.” The operative word there? Can. Maybe Orwell couldn’t admit the debt he owed Eileen. But whether in war or peace he never could have accomplished what he did without her. This extends well beyond typing, editing, and dodging Soviet spies.

Services Rendered

Not only did Eileen shoulder the domestic burden of managing their home with all of its endless, thankless chores, but for extended periods she did so while also serving as the couple’s primary breadwinner. Eileen believed in Orwell’s gift and wanted him to write—especially important, lasting books, not just reviews and essays scribbled out for freelance cash. So, she worked to fund his writing.

He doesn’t seem to have appreciated it. Her letters and the recollections of friends betray a sense of entitlement on his part. Neither he nor Eileen were culturally conservative or traditional; for their wedding, Eileen had the temerity to edit “obey” out of her marriage vows. And yet she was every bit as dutiful as he was presumptuous.

For me the most shocking revelations in Funder’s book were how far those presumptions could go. After Homage to Catalonia, Orwell wrote the novel Coming Up for Air while the couple stayed in Morocco, principally Marrakesh. After completing the manuscript—which she edited and typed—he wanted to celebrate. How? They went to the mountain town of Taddart, and Orwell cajoled Eileen to let him hire a young Moroccan prostitute.

Such liaisons were hardly out of the norm for Orwell. Orwell was sleeping with another woman while he and Eileen were engaged and was serially unfaithful during their marriage, attempting to seduce Eileen’s friends and occasionally forcing himself on women. If he lived today, the question isn’t whether he’d be #metoo’d, but how soon and by how many.

Orwell’s biographers have attempted to ignore, downplay, or spin these revelations—skirting over them, dismissing them, or even suggesting Eileen granted permission, a willing accomplice. This is part of the overall pattern of erasure Funder describes.

What a woman does, or what is done to her, is only mentioned pages after the events themselves, which are described without her. This separates her actions from their effects, her bravery from its beneficiaries, her earnings from the man who lived from them, her suffering from the people who caused it. And when none of that works, women are imagined to have consented to what was done to them—in Eileen’s case, to a completely fictitious “ménage à trois” or an invented “open marriage.”

Yet there’s no evidence Eileen approved of any of this. It’s apparently hard to admit that Orwell simply took advantage.

Some Spouses Are More Equal . . .

Today the easy question about someone behaving as Orwell behaved is this: Do we cancel? Remarkably, Funder says no. Despite it all, she remains a fan of Orwell’s work, especially his incisive critiques of power and its manipulation. What of his own manipulations? “To my mind, a person is not their work,” she says, “just where it came from.”

Conveniently enough, Orwell said much the same and defended authors’ works from attacks—even when deserved—on their character. I happen to agree. Books stand alone from their authors. It takes nothing away from Animal Farm to find out Orwell acted the pig, any more than finding out Eileen helped shape the novel in the first place.

The saddest thing to contemplate? Realizing Eileen may have also collaborated in her own marginalization. She died prematurely of a botched hysterectomy in 1945, trying to save the couple’s scarce money on her treatment. In her letter to Orwell describing the procedure—he was on assignment in France—she confessed she didn’t think she deserved anything better. It represents an entirely different sort of passive voice, one that went back at least as far as their exchanging of edited marital vows.

St. Paul declared marriage a mystery and, while referring to something theological, his words are true on a plain reading. Few arrangements are more mysterious, more psychologically and relationally complicated than what transpires between a married couple.

Even Orwell knew he’d done Eileen wrong. “It wasn’t an ideal marriage,” he admitted after her death. “I don’t think I treated her very well sometimes.” The writing consumed him, and Eileen’s presence allowed Orwell to focus on it to the exclusion of any other consideration—including his wife’s well-being.

In his essay ”Why I Write,” Orwell said, perhaps unknowingly,

I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life.

I can’t help but think Orwell’s martial conduct represents his worst everyday failure. As a divorced and remarried man, I say this cautiously. I have my sins and am in no position to judge. But I am in a position to wonder, if only to prevent my own failures in the future. Rather than address the problem, or so it seems to me, Orwell redoubled his writing efforts, thanklessly pushing more and more of everyday life onto Eileen—thus finding relief in his writing while simultaneously exacerbating the deeper issues.

With a nod to John the Baptist, for him to increase, she must decrease. If a book is born in privacy, it’s only because someone else pays the price.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

I read an almost parallel essay about Edward Hopper and his wife Josephine in "Rembreant is in the Wind". This is beginning to sound like a story as old as time. As I was reading, I was hearing the phrase "I must decrease so that he must increase" and smiled when I saw it at the end. Of course Orwell is no Jesus. Also, I have heard great things about Claire Dederer's book Monster and hope to start listening to it this week. Thanks Joel for another interesting and illuminating piece.

While I agree that a book or any work of art or achievement is separate from the artist, it certainly is easier for me to admire the art when I can admire the artist.

A writer like Orwell, living an unbalanced and thus morally questionable life, reminds me of politicians who do the same. There's an entitlement there that is ugly.

A thought provoking essay that goes beyond the specific case of Orwell and gets to larger questions of balance in life. Thank you.