Narrative Control: How Stories Dominate Our Lives

Reviewing Alissa Wilkinson’s ‘We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine’

I never really read much Joan Didion until last year. She was a name I’d always heard, always known. How could you miss her? But I never felt drawn to her work. When it came to cultural observers, I gravitated toward satirists like P.J. O’Rourke, provocateurs like Camille Paglia, and flamboyant bomb-tossers like Tom Wolfe. That’s who spoke to me. Didion was busy doing something else, maybe talking to different people.

But then it clicked. I couldn’t say why or what did it, though I did notice how many people I respected revered Didion and her work and claimed it held up even decades after she wrote. Pundit Matt Lewis keeps a portrait of her hanging over his shoulder while he writes. Erin Marie Miller—an investigative journalist here on Substack—raves about her.

I gave in and went on a Didion bender in early 2024, tearing through seven of her books in a couple of weeks. I was floored. This had been here the whole time?! Indeed. For them with ears to hear . . .

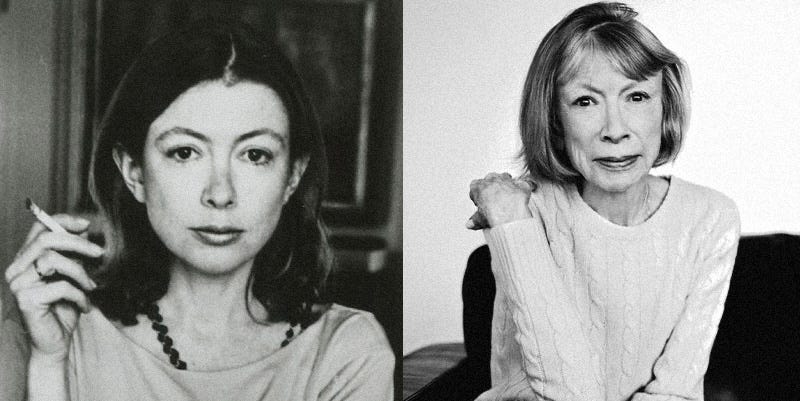

Didion’s style alone justifies the price of admission. Understated and restrained, in some ways she’s the opposite of Tom Wolfe. They both knew how best language worked but used it in remarkably different ways. Both could immerse you in a moment. But Didion somehow made time slow down, enabled you to meditate on the moment instead of rushing through it to the next.

She was cool and dispassionate, alert but rarely triggered. And when a moment did worm its way under her skin, when she lost the plot, she came out and let you know. A moralist without a shred of moralism: I think that was Didion, and that’s what makes her work so fascinating.

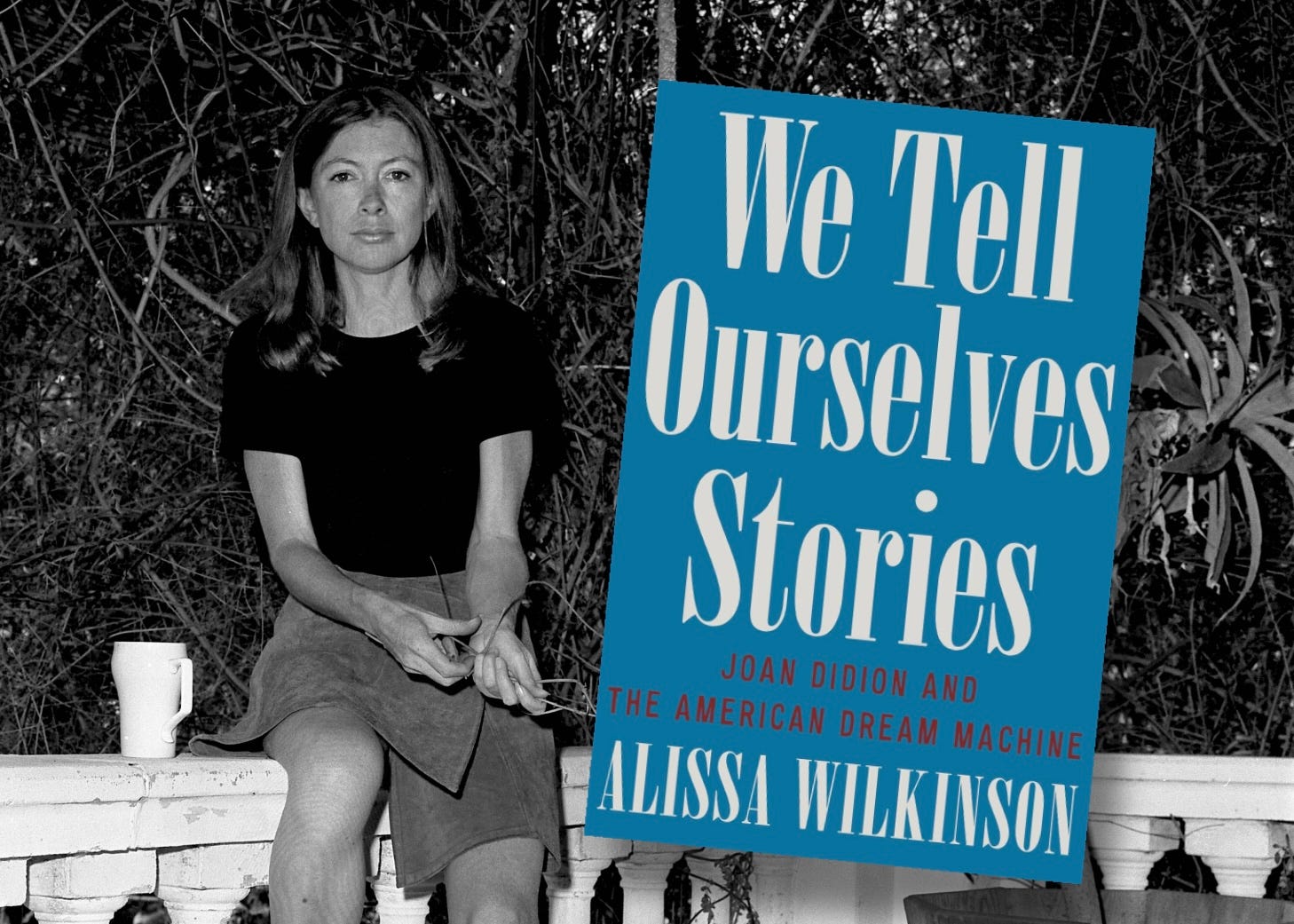

Except it’s nowhere near the whole story—which brings me to Alissa Wilkinson’s illuminating book We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine. I’ve enjoyed Wilkinson’s film criticism in The New York Times. Here she covers something I knew very little about: Didion’s deep involvement in Hollywood and how it shaped her understanding of story, myth, and ultimately reality. Sign me up.

Three Joans

If you had to reduce Wilkinson’s book to one insight, it’s right there in the title, taken from Didion’s most-quoted line: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Do we have a choice? Life hurls too much at us—too many datapoints, details, disappointments, contradictions. Reality is, as a former colleague of mine used to say, a hot-mess express. So we sort and sift and frame and narrate until it falls into some sort of order we can tolerate. And we like it best when someone does the heavy lifting for us.

Sometimes the stories we tell and consume are malarkey, like most conspiracy theories. Other times they’re soothing, like narrative quilts we wrap around the sharp edges to minimize damage when life’s moving van wobbles and jostles around turns and corners. Either way, Didion understood our favorite stories are not always true; in fact, they’re often designed to keep us from the truth.

In my reading, Wilkinson describes three distinct Didions. Beyond her journalism, early-career Didion worked deep inside the Hollywood screenwriting world with her husband, John Gregory Dunne. I knew she’d written some screenplays, but I had no idea about the extent of her involvement. She’d always been interested in film and worked as a film critic. But she was also part of the machine itself: the back-office meetings, the dealmaking, all of it.

Mid-career Didion took what she learned about manufacturing and packaging stories for popular consumption and turned that perspective on politics. Her reporting during the late eighties and nineties revealed how politicians had adopted Hollywood’s playbook—how, for instance, campaigns were like mobile movie sets and how conventions were staged for television. We’re living in the world today Didion tried warning us about then—where news is entertainment and politics is a show.

Late-career Didion turned the skeptical eye on herself. In Where I Was From, she began to deconstruct the myths of her childhood; then in The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights she wrestled with the stories she told herself about her deceased husband and daughter. And the storytelling wasn’t over.

When she turned The Year of Magical Thinking into a play, she used it to shield herself from the grief of losing her daughter. As long as the curtain kept opening, Quintana Roo was alive—onstage, in moving, breathing prose. The story functioned as denial, and Didion knew it. As Wilkinson demonstrates, she understood of the mechanics of storytelling, even how to turn those powers on herself.

Subscribe for More

If you enjoy what I’m doing here, subscribe for more joy! I publish a literary essay and a review every week—and it’s always free.

Pernicious Nostalgia

Wilkinson draws attention to Didion’s concept of pernicious nostalgia. If nostalgia is the tendency to see the past as somehow better than the present, pernicious nostalgia does so with, as she says, “a corroding effect.” We mischaracterize the past to justify ourselves in the present.

And we gulp it down; our politics is suffused in it, suffocating in it. Every contested topic in politics and culture offers examples.

I’ll spare us all a rehearsal to avoid unnecessary polarization, but Where I Was From exposes one case worth attention. For decades California held out promise as the land of opportunity, personal freedom, and individual reinvention. But the entire economic basis on which the story was founded depended, as Didion eventually discovered and described, on denying the origins of the state’s wealth and sustenance.

Heavily subsidized by the federal government, there was little ruggedly individualistic about it; the rest of the nation helped pay for the dream. And Didion’s point was ultimately larger than the Golden State of her upbringing; it was emblematic of America’s self-conception across the board.

The problem is that by mischaracterizing the past, pernicious nostalgia prevents us from understanding our history in a constructive way, hampering our ability to act sensibly in the present. It’s the story the nighttime drunk tells himself before the morning hangover.

As Didion saw it, most of us are sleepwalking through stories. We wade through narratives every day—on the news, on our socials, on our screens, by influencers, by friends, by politicians. And the stories we usually love best are those that most insulate us from reality. Confirmation bias isn’t just a logical fallacy, it’s a coping strategy for modern life.

More on Didion

Having come to this realization, Didion was rarely fooled—except when she did it to herself. And then, didn’t she know? Wilkinson shows us how Didion’s Hollywood baptism equipped her to face the dark side of storytelling and myth mongering as it spread beyond Tinsel Town into every facet of modern life.

In a world of reels and feeds, TikTok and X, Didion’s insights seem more relevant than ever. Whereas movies depend on a willing suspension of disbelief, modern sanity depends on a dogged refusal to suspend disbelief, one of our most valuable faculties. And seeing how far narratives have infiltrated our world makes Alissa Wilkinson’s We Tell Ourselves Stories essential reading today.

Where do you see stories dominating our lives? Comment below. And don’t forget to hit the ❤️ icon and share this review. Thanks!

A very thoughtful and timely essay, thanks for that. I too have been noticing Didion and the attention she’s been getting, all for very good reasons in a time when I find myself citing Mencken and other critics of American mythology.

Nice post! I've only ever read her memoirs and essays, but maybe now I'll read some of her other work. Her 1968 essay on migraine ("In Bed"; though be forewarned its medical details are understandably out of date) was honestly paradigm shifting for me when I first read it 4-5 years ago, as someone who also struggles with migraine and a few other chronic health things. In telling her own story about migraines, she offers a way for me to see them not as an enemy but as my body trying to tell me something, or help my mind rest. I reread it at least 3-4 times a year, and when I meet a fellow migrainous kinsman, I send them a copy of that (rather than the latest medical finding, which I'm also always reading up on). Because medicine can help us manage symptoms, but stories help us do the harder work of living with them meaningfully.