3 Reasons Your Art Might Fail (and How to Ensure It Doesn’t)

Philosopher Agnes Callard Poses a Question; I, a Professional Editor, Venture an Answer

“I have never been able to understand how there can be bad writers,” says César Aira in his novella The Famous Magician. “All the elements required for writing well are right there in Literature, served up on a silver platter.”

Given the ubiquity of literary treasures from which to learn, the opinion makes sense. Still, as Aira admits, he stands contradicted by “overwhelming empirical evidence.” Gobs of poor writing await us, some of it perpetrated by us. We’ve all read or produced enough to suspect, even fear, it could spring at any moment.

And that takes me to a question posed by philosopher Agnes Callard.

Callard’s Puzzle

“Why,” asked Callard, “is it so much more common for a work of art to start well and end poorly than vice versa?” She found herself asking the question when reading Wallace Stegner’s Pulitzer-winning novel Angle of Repose.

Though the book ranks among Modern Library’s 100 best novels of the twentieth century, anxieties welled. “I read the first hundred pages,” she said, “and now I’m scared to continue because what if the rest doesn’t live up.”

We’ve all been there: disappointed by a book that begins promisingly but flames out by the end. Callard’s fear stems from experience, but her question stems from curiosity: Why not the other way around? Why does art that starts badly so rarely get better?

Professionally, I’ve worked with a certain kind of artist: authors. I’ve edited a few hundred books (I’ve long since lost count). I’ve seen authors struggle with this dynamic many times. To whatever extent their experience and mine can be generalized to others, I’d like to hazard an answer to Callard’s question.

I suspect it comes down to three issues: a failure of vision, skill, or character. All three simultaneously explain why it’s common for works to fizzle and why it’s also rare for the reverse to occur.

1. Failure of Vision

If we could chart the progress of an artistic vision across two dimensions, expression mapped along the x axis and specificity along the y, we’d find that some ideas get worse as they become more fully realized. The greater specificity and fuller expression serve only to reveal the inadequacy of the original vision.

When an idea lives only in our heads or inchoate form on paper and screen, the fact that it’s vague and undeveloped is a benefit. We savor our half-baked ideas. It’s when we’re forced to more fully articulate them that we realize—or others realize—our ideas stink.

If you follow the progress of a book from initial concept through its various stages, you can see how it goes. As the author begins building out the concept in notes and outlines, possibly drafting a chapter or two, and then finally settles down to pen a proposal, the original vision takes more complete shape.

Sometimes an idea will fall apart in that process and will be abandoned, though not always. I worked once with a bestselling author who was stuck on a new idea. We wanted a new book, and he had it! At least, he was convinced he did. It was terrible. The more he talked about it the worse it got. As evidence even he knew—despite his protestations to the contrary—he never developed the proposal past the most rudimentary shape. His reserve was a form of self-protection. Fully articulating the idea would have exposed it as lousy.

Most nonfiction books are bought on spec, based on the proposal alone. Sometimes the inadequacy of an idea reveals itself as the book is being written; it doesn’t come together as originally envisioned. The vision itself could be to blame in such cases, but there are other possible culprits as well, including insufficient skill.

2. Failure of Skill

“Every time I sit at my desk,” said Fran Lebowitz, “I look at my dictionary, a Webster’s Second Unabridged with nine million words in it and think, All the words I need are in there; they’re just in the wrong order.” Some writers are better at the task than others. I have, for instances, been enthralled with Joan Didion. She knew how rearrange a dictionary. But we’ve all read work where the author’s lack of skill became a liability.

It’s the core fear behind Callard’s question. Her hopes were high—the original vision was compelling. But what if Stegner couldn’t pull it off? This is at the root of César Aira’s observation. Indeed, “all the elements required for writing well are right there,” but some authors simply can’t satisfactorily stitch them together. The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.

And so we get a novel or narrative nonfiction book that begins well, but the author loses something along the way. Perhaps the writing is stylistically lacking, or the pacing is off, or they mishandle characters, or their dialogue feels forced, or—some combination of these and other faults. The possible problems are endless.

While his royalty checks no doubt salve the humiliation, thriller writer Dan Brown can’t publish a sentence without critics noting his godawful prose. When Inferno came out in 2013, reviewers savaged the effort—some by parodying his style for laughs, others by more direct pronouncement. “As a stylist Brown gets better and better,” said Jake Kerridge at the Daily Telegraph: “where once he was abysmal he is now just very poor. . . . In the end this is his worst book, and for a sad, even noble, reason—his ambition here wildly exceeds his ability.”

What Brown has going for him that lesser novelists do not? A work ethic. The work might be shoddy, but he reliably cranks it out. And that leads to the third part of my answer.

3. Failure of Character

I hesitate labeling this final reason a failure of character, but to the extent undermines an author’s work I’m not sure how else to express it than as a personal flaw. It fits. In my experience two particular faults can manifest, though each might sprout into several others.

Pigheadedness. While an author’s contract stipulates the publisher’s right to prepare their manuscript for publication—including all the editing necessary for the endeavor—some authors refuse to be sufficiently edited. When a book is on a schedule with revenue attached to its release, an editor may cave and let inferior work out the door to ensure their department makes its budget.

Procrastination. Sloth stands as the least salacious of the Seven Deadlies, but editors know it’s secretly the worst of all. It robs the reader of a book with ample time given to its preparation. Late writing affects the entire editorial schedule. Given the release date and budget concerns already mentioned, pressures can mount to ship a book even it’s premature.

Writing a book isn’t easy. “It’s like being an ant crossing the road,” said philosopher Mary Midgley. It’s worse when a person rejects expert help or dallies along the way. A book can suffer from a failure of vision and an author’s lack of skill and still emerge in decent shape if an editor is free to do their job. But if an author bristles at input or drags the output, there’s only so much than can be done to make up for the deficits.

Returning to Callard’s puzzle, a work of art fails for both aesthetic and practical reasons. The author demonstrates a lack of vision, skill, or character to put it over; the seeds of the failure are sown from the start.

And why doesn’t this go the other way? It would require a strange universe where someone lacking vision, skill, or character could end up displaying all three in a final work. That is, it started bad for good reasons; those reasons are not likely to allow the work to ever turn around. I’ve started writing several novels and never completed a single one for a combination of all three reasons. Successful artists, on the other hand, demonstrate particular strength in these three areas.

When Art Succeeds

A few examples come instantly to mind. Before he begins writing a novel, Amor Towles spends a lengthy time testing his vision, ensuring it can withstand greater specificity and fuller expression by fleshing it out in advance of writing. “When I come up with an idea for novel,” he told podcaster Russ Roberts,

I will spend several years designing the book. . . . I will spend a few years imagining it. What happens? Who are these people? What are the settings like? What are the events? What does it sound like? What are the issues at play? What’s the minutiae that might be a part of this canvas? And, that involves not only dwelling on it and thinking about it, imagining it, but ultimately filling notebooks with potential passages for the book once I get around to writing it. Once I’ve fully imagined the book after a period of years, then I outline it in some detail, having that knowledge now in hand. To me that outline is 30, 40, 50 pages. So, it’s quite detailed.

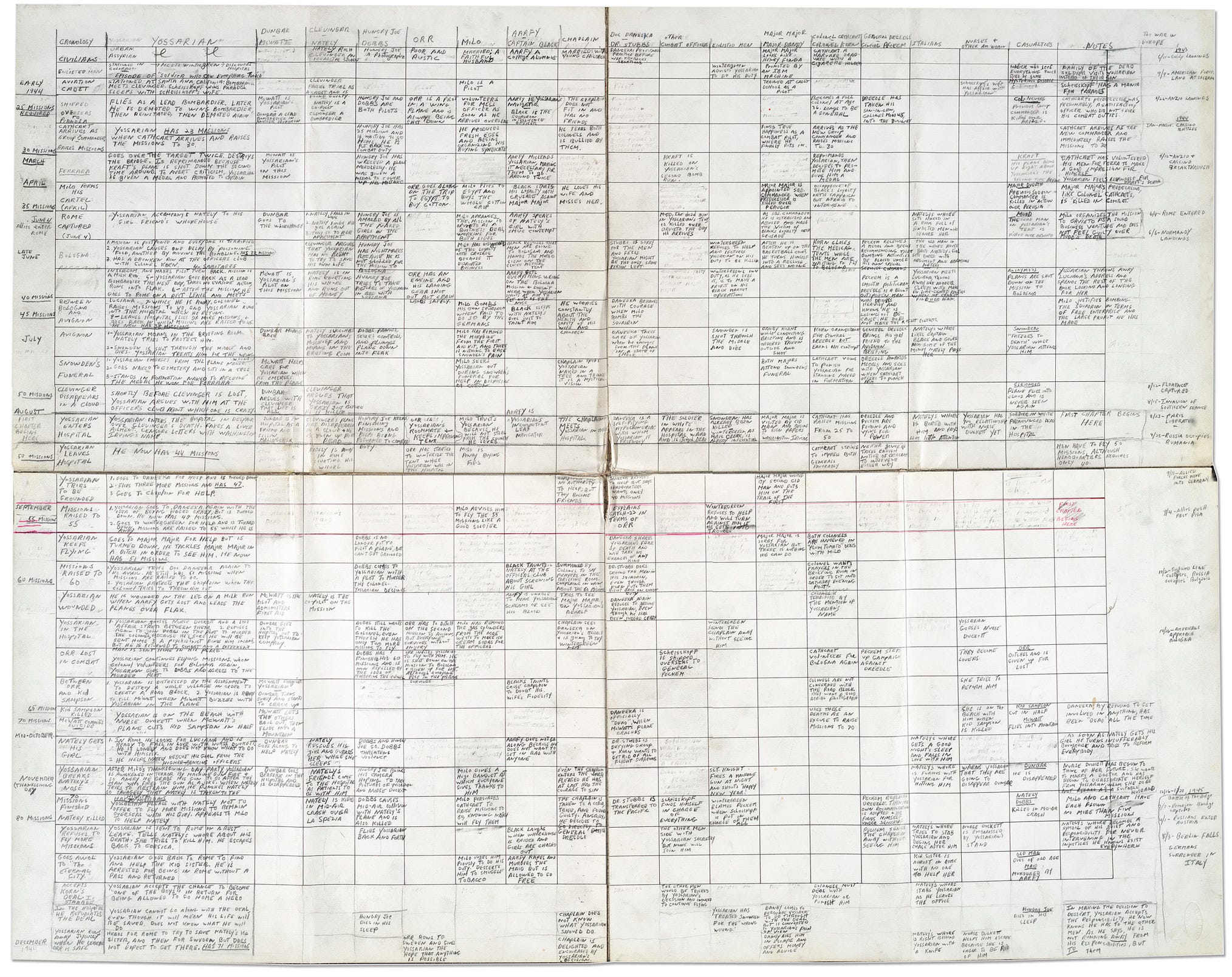

It’s an incredible insight into his process and one that reveals how dedicated Towles is to perfecting his vision up front. Joseph Heller approached the complicated plot of Catch-22 in related fashion, creating a massive hand-scrawled spreadsheet to organize the key events along the story’s scattershot chronology.1

Contrast that approach with Dean Koontz and Haruki Murakami: no outlining for them. Back to the articulation chart, their vision gets better the more fully it’s realized, thanks to a combination of their skill and character, specifically their worth ethic.

Both authors let their initial idea follow its own evolution based on the constraints of the story. “I give the characters free will,” says Koontz. “The novel becomes organic and unpredictable and much more interesting to me.” He stays on track by extensive self-editing and rewriting, reworking a single page twenty times or so before moving on.

Murakami works in similar fashion. “No matter how long the novel is,” he says, “or how complex its structure, I will have composed it without any fixed outline, not knowing how it will unfold or end, letting things take their course and improvising as I go along. This is by far the most fun way to write.” Unlike Koontz, Murakami writes straight through his first draft and then irons out all the narrative kinks in several exhaustive rewrites.

Koontz works ten hours a day, six days a week, to see his projects to completion. Murakami commits to 1,600 words a day.

Examples like these four novelists remind us what it takes for a book to end as well or better than it starts. I don’t see how someone without similar commitments could swing it. “All the elements required for writing well are right there in Literature, served up on a silver platter.” True. But it only counts if you develop them for yourself.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Importantly, Heller was also open to editing. He worked with the famed Robert Gottlieb. “Some of Bob’s suggestions for Catch-22 involved a lot of work,” Heller recalled. “There was a chapter that came on page two hundred or three hundred of the manuscript . . . and he said he liked this chapter, and it was a shame we didn’t get to it earlier. I agreed with him, and I cut about fifty or sixty pages from the opening just to get there more quickly.”

Great post…I couldn’t help but muse that so many of the characteristics of bad writing you described can be applied to the analysis of our culture’s pet ideologies…failure of vision: first stage thinking that can’t survive a deep examination; failure of character: pigheadedness/ego/narcissism, sloth…

This was an excellent post. I absolutely loved Angle of Repose by Stegner on your recommendation. Every word of it. I also loved Gentleman in Moscow by Towles. I have reserved Rules of Civility. I also plan to reread Heller. An author I am sure I found on your website is Abraham Verghese. I read Cutting and Water and was still crying 3 days later for fictional characters. Excellent reads. Thanks for your interesting articles. Looking for next Murakami. Agree on Dan Brown. Read one, gave up.