Trapped in a World You Didn’t Choose

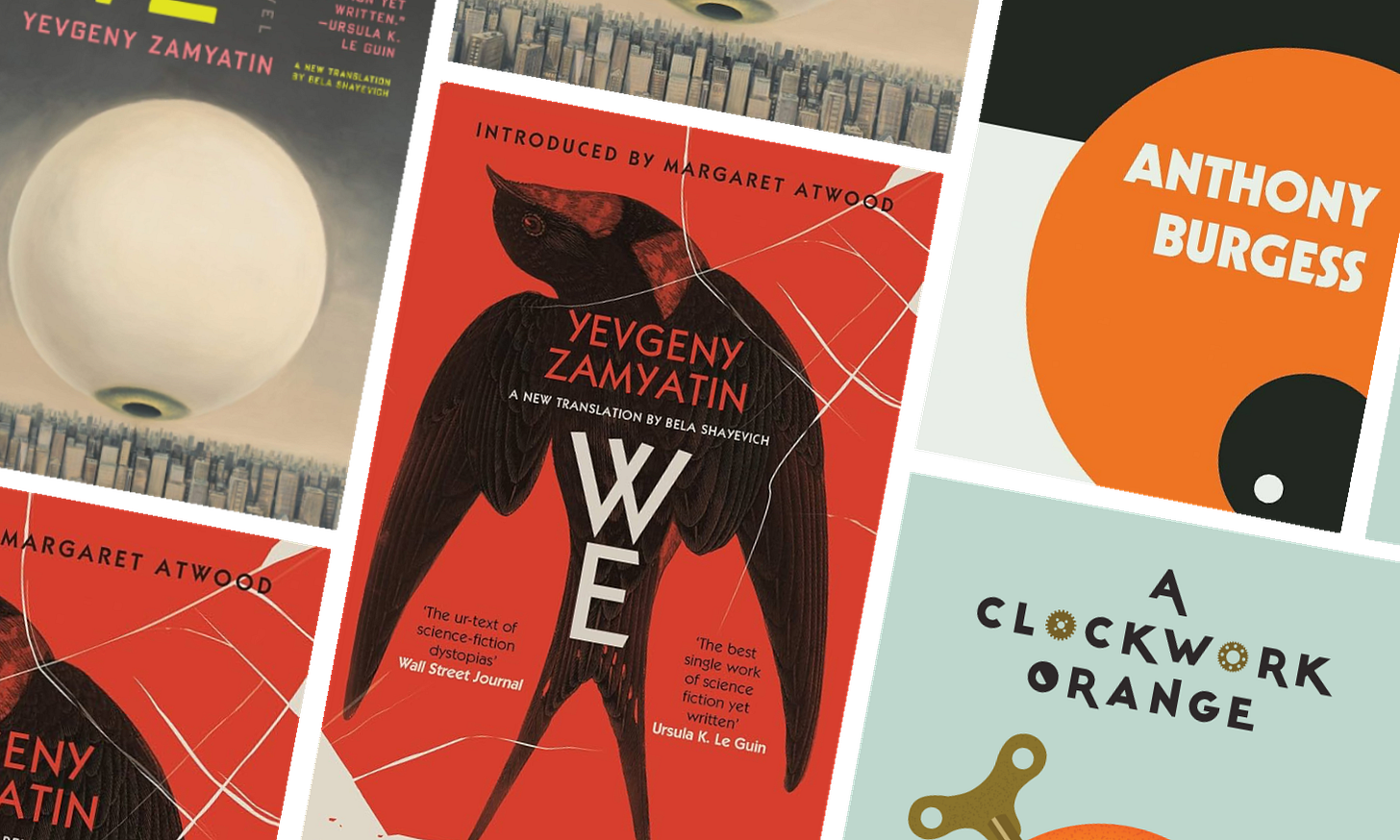

The Choice to Escape: Reviewing Yevgeny Zamyatin’s ‘We’ and Anthony Burgess’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’

Stories turn on struggle, and literary theorists tell us there are a handful of universal conflicts: man versus self, versus man, versus fate, versus nature, versus technology, versus the supernatural.

Another? Man versus society.

Sparks are bound to fly for individuals born into a world with preexisting expectations, norms, laws, and structures. We know this from our own experience: Nobody asked us. We didn’t consent. We didn’t vote. And there’s no opt-out form. We’re just here. We’re stuck.

A Number, not a Name

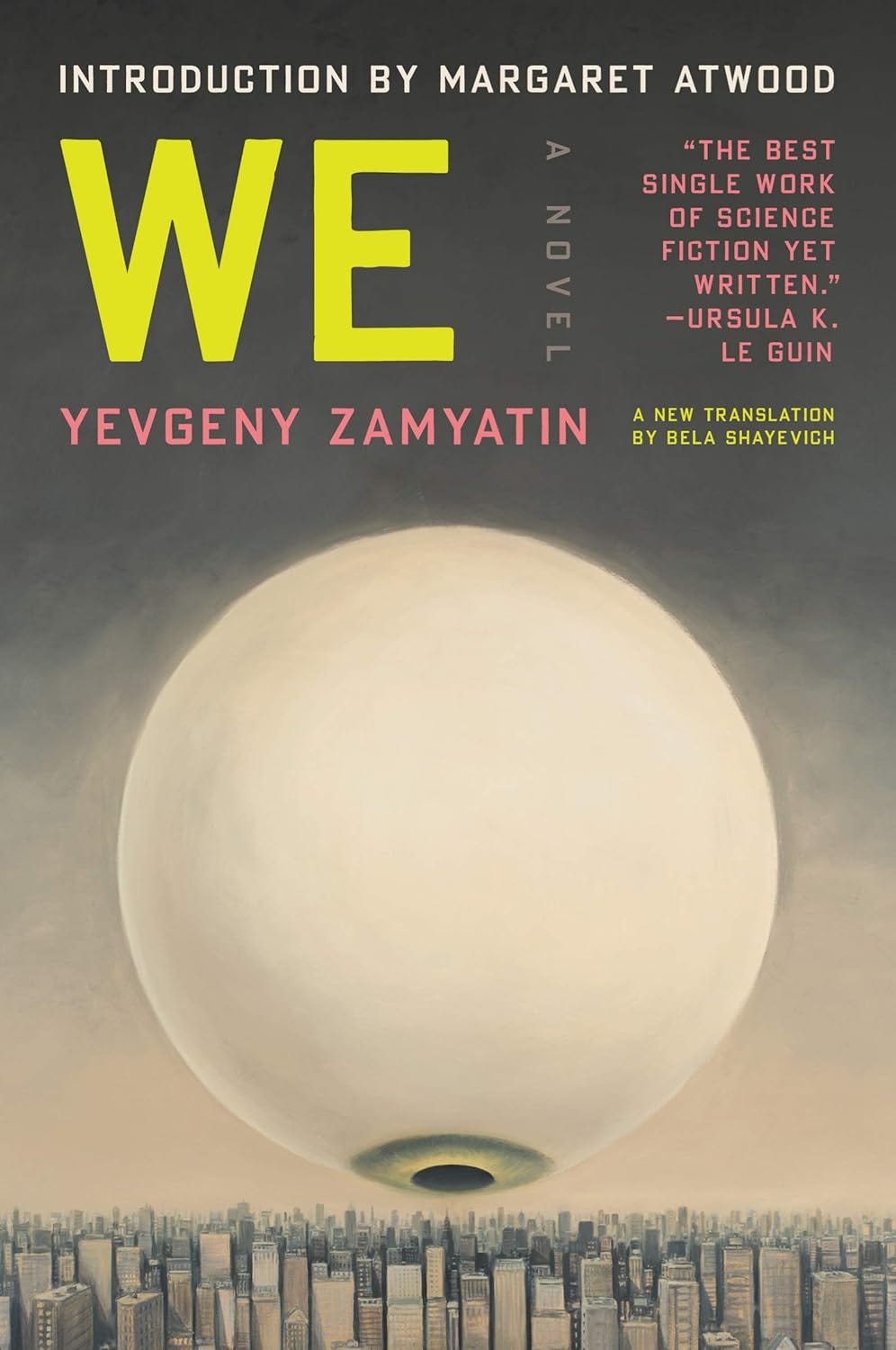

The nature of such stories depends on the nature of the society and the individual(s) bucking the yoke. Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, written in 1920 and ’21, imagines a future world of extreme regimentation and conformity under a godlike dictator known as the Benefactor. Within a walled city state, the One State, schedules are universal and prescribed; everyone dines at the same time, exercises at the same time.

Numbers replace names. People live in glass towers, always visible to their neighbors except during sex when blinds may be temporarily lowered. Marriage is no more. People request sexual partners from the One State and trade pink tickets for trysts. The only truly free time is a daily personal hour, in which the last vestige of individuality can find an inkling of expression within suffocating societal constraints.

D-503, our unlikely protagonist and vacilating narrator, can’t fathom anything else—at least initially. The lead engineer working on a deep-space rocketship called the Integrator, D-503 has been asked to contribute a diary of his thoughts about the project and life within this ideal society as a means of evangelizing civilizations on other planets.

D eagerly undertakes the assignment, his personal logs forming the narrative, a confessional of sorts.

I Confess

A Clockwork Orange also takes the form of a first-person confession. Instead of the distant future, however, Anthony Burgess’s tale unwinds in an unspecified but distinctly near-future urban version of sixties England—though one bleaker by far: filthy, impoverished, and beset by violent teenage gangs.

Protagonist Alex does his part to worsen the crime statistics. A typical evening for Alex and his crew? While his parents think he’s out odd-jobbing, Alex and the boys get high, buy off old women to lie about their whereabouts, and then wreak havoc on their unfair city: brawling, mugging, robbing, breaking and entering, raping.

The first third of the book is an unrelenting parade of mayhem, Alex recounting how he and his “droogs” do their worst with zero remorse. Droogs? The word means friends or fellows in Alex’s criminal patois. Burgess’s teenage sociopath relates his entire tale in an invented slang. Mercifully, in fact. While the reader quickly picks it up, the lingo actually helps create narrative distance from the deeds they depict, a screen that shields the imagination from what more direct description might sear in the mind with a sizzling, hot brand.

Burgess complicates the reception of his ne’er-do-well narrator in a few other ways, too, which helps because he holds nothing back. For one, Alex is amusing. For another, he’s cultured; besides kicking people in the head, nothing sends him into ecstasy like classical music. Finally, he’s not utterly evil: Yes, he kills people—a few, in fact—but the deaths are accidental.

Motive to Rebel

Both Zamyatin and Burgess are interested in the conformity demanded by society and what drives individuals to recoil. Alex begins his story in full-blown rebellion; to his mind society’s a con job, and he might as well run his own racket. D-503, on the other hand—a true believer—takes a little persuasion.

That comes in the form of I-330, an alluring woman living on the margins of acceptible behavior. As D-503 discovers, she actually lives far beyond the line, even conspiring with a group of insurgents to destroy the suffocatingly stringent established order.

I craves freedom, hates the Benefactor and the One State, and needs D to help her in the cause. Entranced by the combination of her beauty and inexplicable willingness to flout norms and laws, D falls like a domino. He begins dreaming for the first time in his life and feels emotions he never before knew, believing both represent some form of mental illness.

He embraces the affliction and describes his descent in his logs, revealing all—including plenty of hesitation and cognitive dissonance—along the way. Another, larger domino stands behind D, the explicit target of I’s scheme. The question is whether D will let himself fall far enough to knock it down as well.

What individuals will and won’t do to assert their personal desires against the grip of society forms a central question in both novels. And both present scenarios where their protagonists are forcibly deprived of their ability to choose. After all, what is allegiance if it’s nonconsensual? What is participation if it’s coerced?

No Choice

In We, Zamyatin’s climactic sequence involves a newly discovered procedure, the Great Operation, that surgically alters the brain’s ability to imagine. Deprived of imagination, future humans can become as perfect as flawlessly engineered machines—walking, talking syllogisms, stepping in time with the will of the One State.

In A Clockwork Orange, Burgess gives us the Ludovico Technique. Finally apprehended for his misdeeds, Alex finds himself behind bars and eventually forced into a new treatment that promises to reform and release him in just a fortnight. At first he’s excited by the prospect of finally being free again; then he’s strapped in the chair.

Drugged and restrained, his eyes pinned wide open, Alex is forced to watch an endless display of human depravity and violence on film, all set to his favorite music. The combination of the drugs and visuals trigger pscyhosomatic changes in Alex that make it impossible for him to contemplate violence or sexual wrongs without becoming physically ill. Rendered neutered and inert, Alex is set free—unable to harm anyone any longer.

“He will be your perfect Christian,” says the doctor who effects this miraculous cure, “ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify, sick to the very heart at the thought even of killing a fly.” But the prison chaplain, an alcoholic priest who takes an interest in Alex, knows better.

“What does God want?” he asks Alex. “Does God want goodness or the choice of goodness? Is a man who chooses the bad perhaps in some way better than a man who has the good imposed upon him?”

A human without choice, without a will, is not human. Alex somehow knows this as well. “Am I just to be like a clockwork orange?” he asks, invoking the titular metaphor, an icon of the artificial, the fake.

Tale of Two Receptions

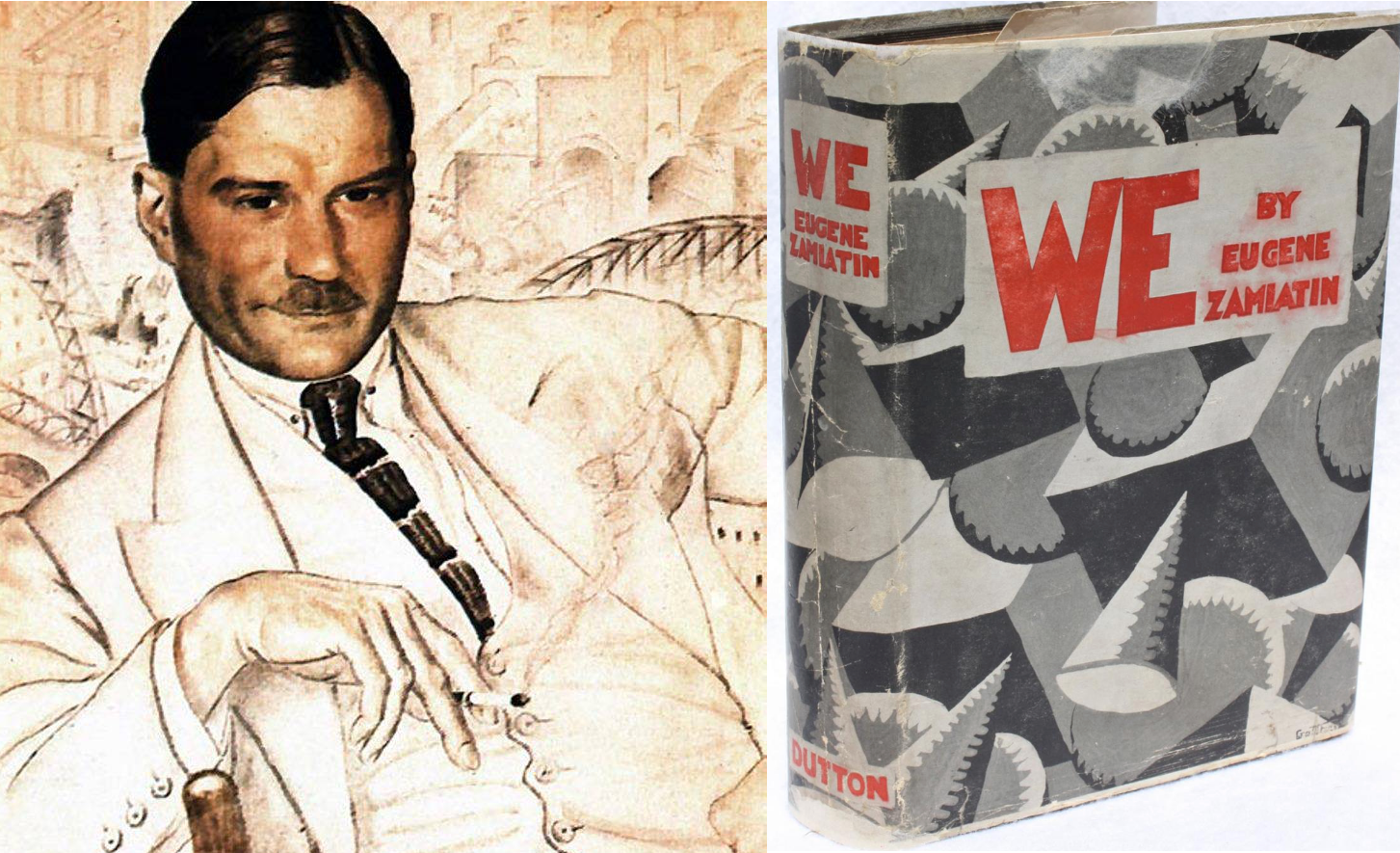

Written four decades apart from each other, We and A Clockwork Orange share themes and concerns but significantly different fates. Zamyatin, the son of an Russian Orthodox priest, rejected his faith and joined the revolutionary Bolsheviks but retained enough residual Christianity to also reject the Soviet insistence on sacrificing individual wills to the communist state.

We formed part of Zamyatin’s protest. No surprise: The government rejected its publication. Zamyatin smuggled his manuscript out of Russia, and the book was published in English by Dutton in 1924—much to the irritation of the commisars—long before it found its way into the Russian language. The first full Russian edition was published in America (!) in 1952 and the book had to wait until 1988 before it could be openly published in Russia.

Zamyatin never saw the day. After petitioning Stalin to emigrate, he left Russia in 1931 and died in obscurity in Paris six years later. Hard to come by, the English edition eventually found its way to George Orwell. It influenced 1984 and bubbled largely undetected under the surface of Western science fiction ever since.

Written in 1962 in Britain, Clockwork faced a much different reception. The Western world of the 1960s were considerably more welcoming of the individuality championed by Burgess. The original American edition dropped the final chapter, which, if anything, made the book even more transgressive. And Stanley Kubrick’s controversial 1971 movie adaptation only perpetuated its fame.

How we read and evaluate man-versus-society narratives depends on what kind of society is depicted and what kind we inhabit. Zamyatin’s society devalued the individual and so repressed his work. Burgess’s society celebrated the individual and thus left his work free to find whatever audience might respond to its message.

Both warrant our ongoing attention today.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out!

While you’re here, check out:

It was a pleasure to see your reviews return.

I have not read either book and had never even heard of We, which intrigues me.

On a milder level of dystopia perhaps is a personal favorite (still have the Doubleday Science FIction hardback) - Theodore Tyler's "The Man Whose Name Wouldn't Fit" about Mr. Cartwright-Chickering's war against the machine after finding that the bureaucracy was erasing him because his name wouldn't fit in the alloted spaces on the all powerful computer punch cards. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6576774-the-man-whose-name-wouldn-t-fit