Why Is Axe Murder Funny? Why Is It Captivating?

Reviewing Rachel McCarthy James’s ‘Whack Job’ and Andrew Klavan’s ‘The Kingdom of Cain’

Tools have a bias toward some uses more than others. It’s an argument I make about books in The Idea Machine, following the observation of media theorist Douglas Rushkoff. “People like to think of technologies . . . as neutral,” he said, “and that only their use or content determines their effect. Guns don’t kill people, after all; people kill people. But guns are much more biased toward killing people than, say, pillows.”

As I mentioned, I first applied the thought to books—but more recently my mind has veered toward hatchets.

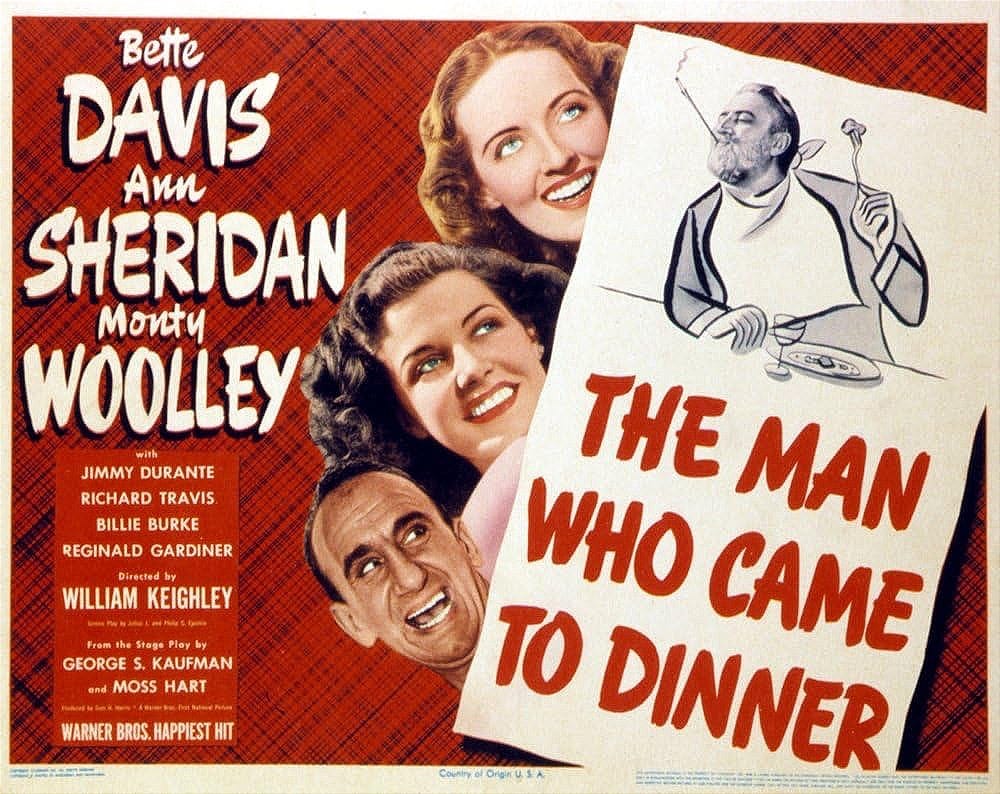

Browsing through the wonderfully-merchandized shelves at the Yankee Bookshop in Woodstock, Vermont, back in September, I happened upon Rachel McCarthy James’s history of axe murder, Whack Job. How could I miss it? The axe is pointed away from prospective readers, but the cover hits you right between the eyes. There’s something grisly about the design, including the unsubtle hint of blood. But there’s also something funny about it. It’s right there in the title; we’re meant to chuckle.

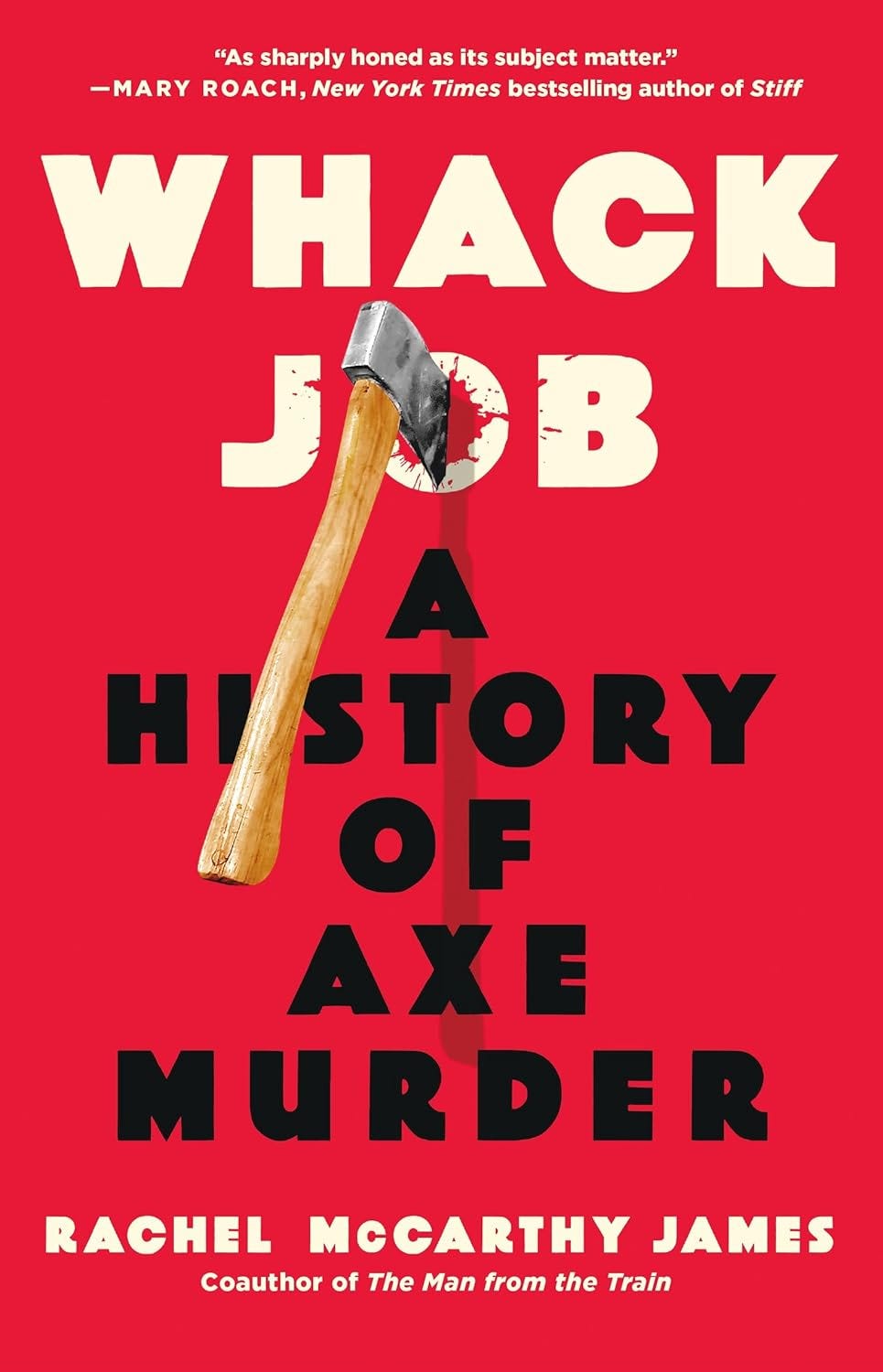

The first time I ever noticed axe murder played for a joke was in the 1939 play The Man Who Came to Dinner. I saw the movie adaptation (starring the wonderful Bette Davis and the hilarious Monty Woolley) sometime in high school.

Woolley plays the boisterous critic and radio personality Sheridan Whiteside. Injured while slipping on ice visiting the Stanley home, he’s forced to stay at their house while he recuperates—and proceeds to make their life miserable with his antics and meddling. At last, near the end, Mr. Stanley finally conjures a way to evict his pestiferous guest. But Whiteside has other ideas and no plans of leaving.

From out of nowhere he plays his trump card: He knows Mr. Stanley’s oddball sister, who lives in the house, is in fact the infamous axe murderer, Harriet Sedley. He then threatens to broadcast the dark family secret, punctuating the threat by rattling off a jingle:

Harriet Sedley took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks,

And when the job was nicely done,

She gave her father forty-one.

The story is fiction, but the reference is real. You may know the jingle goes back to an actual case: the 1892 double axe murder of Andrew and Abby Borden. Their daughter Lizzie was charged but found not guilty at her trial; still, the catchy taunt lingered long, long after: “Lizzie Borden took an axe. . . .” I heard kids chant it at school in the 1980s. There was something ghoulishly goofy about it.

Comedian Mike Myers was paying attention. So I Married an Axe Murderer flopped in theaters in 1993 but became a cult classic in the years following. In the story, Myers plays a man who suspects that his girlfriend—also named Harriet, amusingly enough—might be a serial killer who slays husbands on their honeymoon. So why is axe murder so funny?

Rachel McCarthy James speculates it’s because axe murder is now so anachronistic; there are better ways to kill people these days. That’s part of it. Axe murder is brutal—and also increasingly absurd, which explains why the title gets tapped for such corporate events as “So I Hired an Axe Murderer: Learn to Minimize Risks in the Hiring Process,” an example James cites in the book.

But then we were playing it for laughs all the way back in 1939. Newspapermen employed the term “axe murder” for shock value in headlines throughout the 1920s and ’30s. Naturally, the shock eventually dulled. “It had begun to cross over into farce,” she writes. The Man Who Came to Dinner led the laugh track but was followed by others. “In the 1940 comedy I Love You Again,” says James in one example, “Myrna Loy says, ‘I don’t care if he was an axe murderer!’ of her lover William Powell. . . .”

Still, drifting from horror to humor wasn’t simply a function of overexposure; the Lizzie Borden jingle goes back as far as 1893—long before the surfeit of sensationalist headlines. Dark humor provides a way to cope with ghastly occurrences. But could it also have something to do with, per Douglas Rushkoff, the inherent bias of our tools?

James’s book is dedicated to the long history of people getting offed by the sharp end of a ubiquitous tool. She traces the story back into prehistory, when our forebears knapped stone axes for routine tasks; the archeological record shows evidence of axe murder all the way back, written in the damaged skulls of its victims.

She follows case after case—medieval battles, early modern executions, and contemporary local news. She even has a great breakdown of the Lizzie Borden story. But there’s another side to Whack Job.

All through the book, James deals with the axe as a practical tool, one less common today but once an everyday feature in most every home. In between the primary narrative chapters she highlights examples of different types of axes—many of which have humdrum workaday purposes: the shingling hatchet, roofing hatchet, cooper’s axe, fireman’s axe, boy’s axe, and so on. Humor often depends on the incongruity and distance between what we expect and what actually happens. The bias of an axe usually involves chopping and splitting wood. When we move to heads, we introduce the sort of surprise that lends itself—however perversely—to laughs. It’s how we can see a title like Whack Job and be amused, instead of repulsed.

But explaining the appeal of a book like James’s through humor alone leaves something out. The mechanics of murder might fascinate, and we might make light of them, but other issues persist. Murder says something about our tools; more profoundly it says something about ourselves. The bias of an axe may tend toward wood, but why it occasionally cleaves someone’s scalp is a deeper question that has captivated us since Cain and Abel.

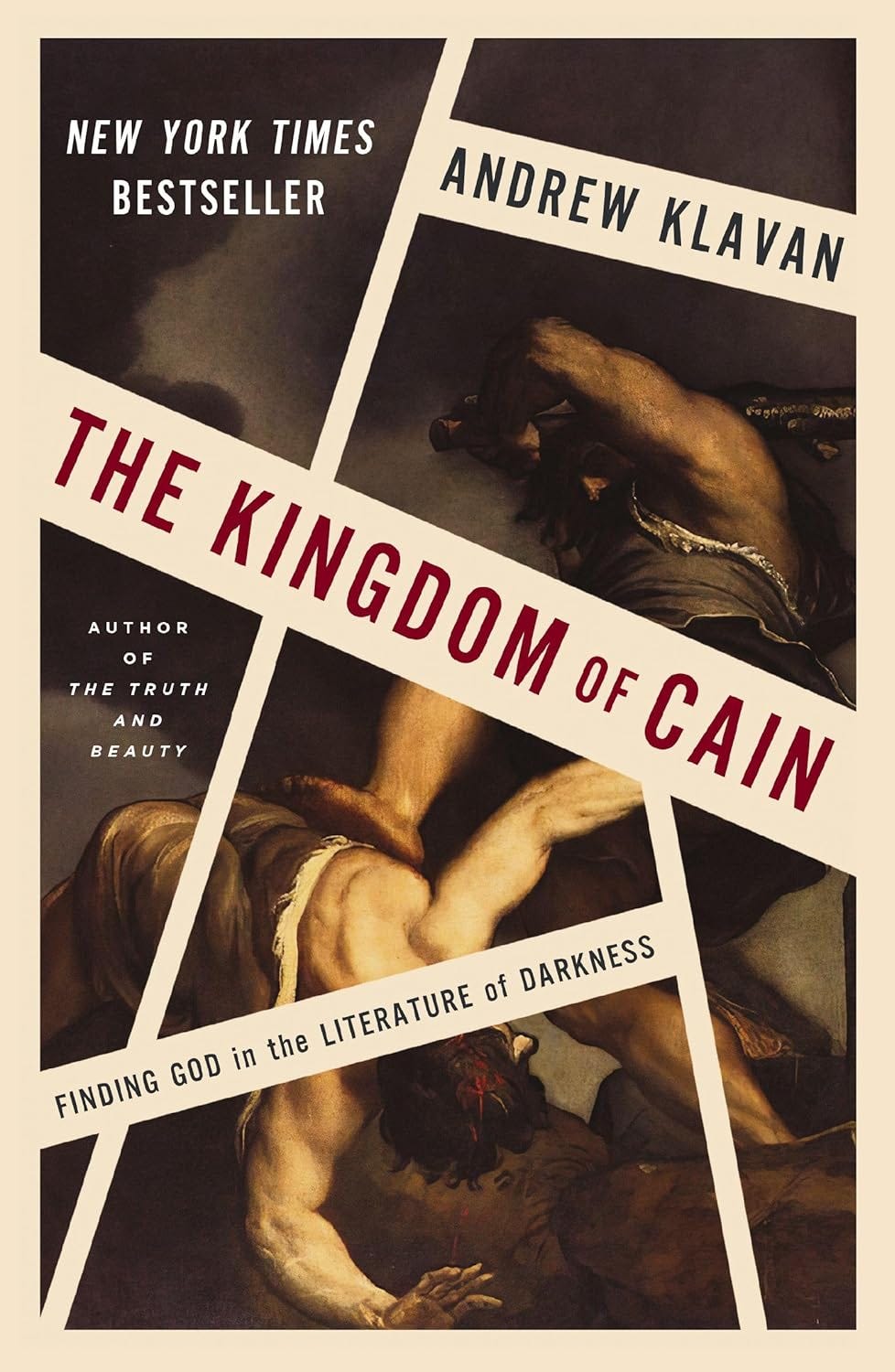

James entertains that interest and offers a rewarding read so far as she goes, though for the heftier moral quandaries I recommend screenwriter and crime novelist Andrew Klavan’s latest nonfiction exploration of the subject, The Kingdom of Cain. Whereas James gives us the cultural history of axe murder as spectacle, Klavan wants to know what murder itself tells us about the human condition.

“My premise is simple,” he begins: “murder is evil. As such, it exposes a path of thought or feeling that the human heart or mind has taken that it should not have taken.” Klavan moves past the bias of the tool to the bias of the heart. He does this by exploring three famous murders and then following their cultural impact as refracted through popular novels and movies.

He starts with the case of blackmailer Jean-François Chardon, rumored to hide his ill-gotten gains in his suburban Paris apartment. One December morning in 1834, two opportunist killers, Victor Avril and Pierre François Lacenaire, showed up to help themselves to the stash. Unknowingly, Chardon let the men inside, whereupon Lacenaire stabbed him staccato style with a sharpened file. In the struggle, Avril saw—what else?—an axe hanging from the door and finished the job, burying the blade in the conman’s head.

Hard to laugh this time. Also hard to look away for long.

The bloody scene could have been the end of the story. Instead, Lacenaire turned the subsequent trial into a publicity event, becoming one of the most popular, if infamous, and somehow sympathetic celebrities of the day. In his version, told in his jailhouse memoirs and to fawning admirers who visited him in prison awaiting the guillotine, he was the victim—the murderer masquerading as martyr.

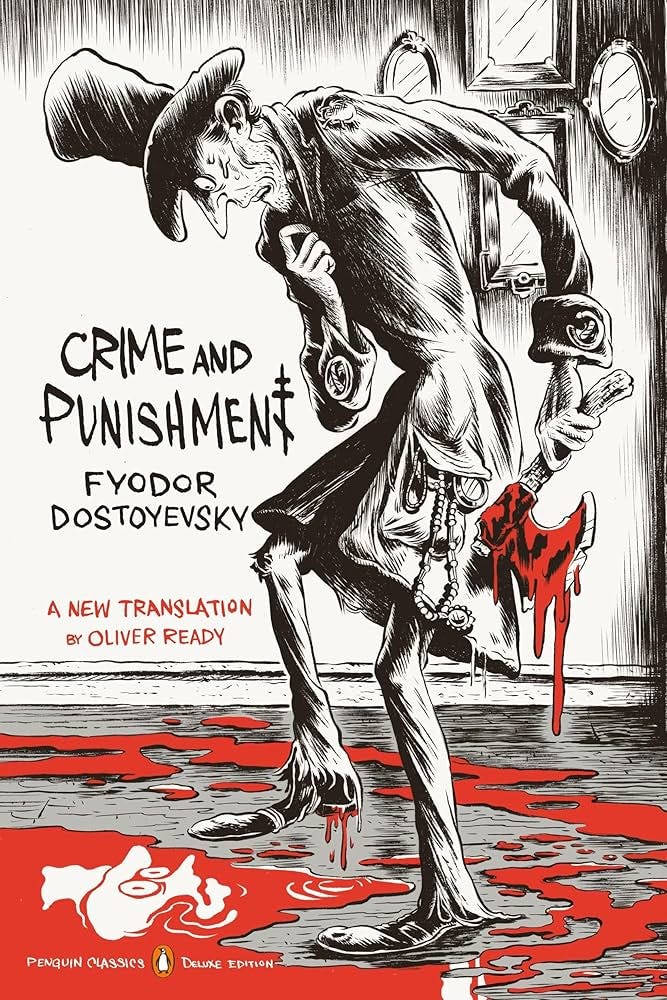

The whole story yielded psychological and spiritual inquiry that landed like a spiky seed in the mind of Fyodor Dostoevsky, who transformed the raw material of the case into his famous novel Crime and Punishment.

Klavan reaches into the annals of crime to trace the linkage to art, asking what such novels as Crime and Punishment and movies as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho tell us about the moral dimensions of the human soul and ultimately what murder reveals about transcendent realities.

It’s a disturbing journey, at moments so gruesome I had to put the book down. But then Klavan takes a surprising turn—one where the distance between expectation and experience points not to laughter but awe.

He concludes with a meditation on Michelangelo’s Pietà, the moment frozen in marble when a mother cradles her murdered son in her arms. It’s a scene that has played out endless lamentable times in history, but this moment is different. What does murder tell us when our victim is God? And what does it say that we can find beauty in the violation?

“We live in the kingdom of Cain,” says Klavan. “But if out of our suffering such beauty can come, then surely there is another kingdom.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

See also:

And check out my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future! Is it one of the best books published in the last twenty-five years? You’ll have to tell me. Interintellect founder Anna Gát calls it “the best Christmas gift you can get for anyone you know who loves books and ideas.” Who am I to disagree?

Oh, fascinating. Makes me want to read "Crime and Punishment," which I've never read. Also, if you've never seen the "Pieta" in person, which Klavan did a great job of describing, it is quite stunning—like all of Michelangelo's work. It just arrests you with the humanity of the scene, the incredible beauty and tragedy of that moment. I can't really put it into words and trying to is only making me frustrated. It's worth beholding in person and gives you some sense of what Nietzsche meant when he said, "God is dead . . . and we have killed him."

Sometimes I wonder if we see humour in gruesome murder due to a failure of imagination. Either we have dehumanized the victim, or we cannot truly envision how horrific it is to so crush and mutilate a living person.

Take Klavan's example of the murdered blackmailer: Blackmailers were viewed as the scum of the earth in the Victorian era. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has Sherlock Holmes decline to investigate the murder of a blackmailer, expressing the opinion that the blackmailer deserved it. Lacenaire was probably viewed as a public benefactor for removing a hated parasite. The victim was viewed as less than human.

I have read the murder scene in Crime and Punishment, and found it horrific. Perhaps it is because I have worked to heal the wounds of the human body, and have felt how it flinches and quivers even while unconscious under the necessary surgical knife, but I can never view with complacency the deliberate, careless mutilation of the human body. It required a suspension of disbelief and faith in Dostoevsky's skill for me to keep reading C&P after that murder scene. Skilled storyteller though he is, he barely convinced me to have sympathy for the murderer. I think a lot of people who are fascinated by gruesome spectacle are either drawn because they cannot look away, like a snake fascinates its prey, or they cannot imagine how it feels if it isn't happening to them.