When All Your Stories Get Scrambled

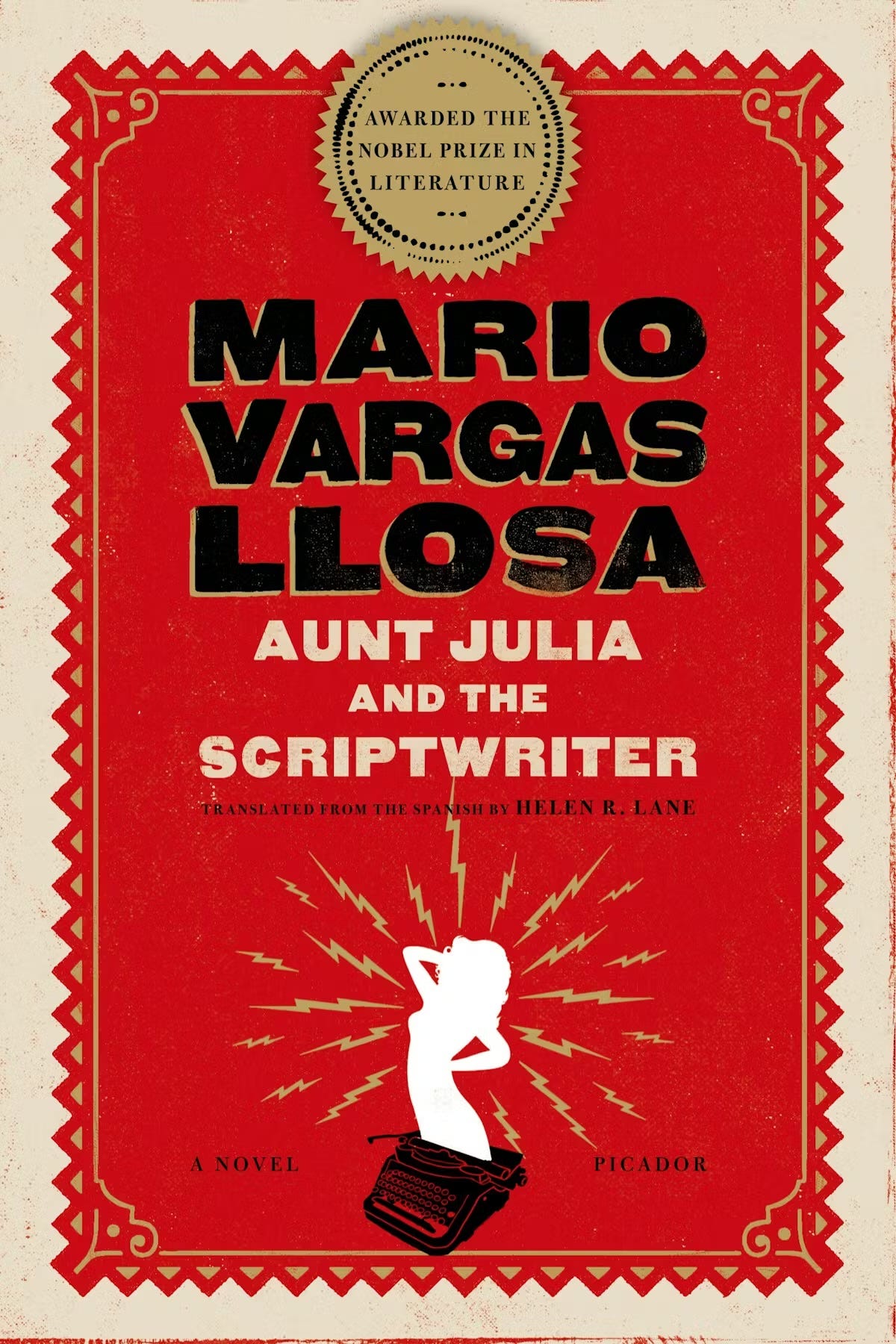

Reviewing Mario Vargas Llosa’s Classic Comic Novel ‘Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter’

Life presents a rough draft you never get to revise. So what happens when your story spins off in a direction you never imagined or, worse, becomes utterly unintelligible? Peruvian literary giant Mario Vargas Llosa explores the problem in his 1977 comic novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, first available in English in 1983.

It’s the early 1950s, and Mario is an eighteen-year-old aspiring writer who works for his local radio station in Lima, Peru, plagiarizing news bulletins for broadcast. He wants to get his law degree. Scratch that. It’s Mario’s large and overbearing family that wants him to practice law; he’s not so sure. He really wants to live abroad in a little Parisian garret and knock out novels for a living.

Mario doesn’t lack for material. Working at the news desk, orbited by odd and colorful people, he hears all sorts of stories he might coax into literature, alchemizing them into short stories. Unfortunately, most of his attempts fail. His youth and inexperience outstrip his aspiration and talent.

Mario might have a potential, if unlikely, mentor. The father-and-son owners of the radio station, the Genaros, have recently lured a celebrated radio soaps writer to come work for their station. No one could keep Bolivian listeners on the edge of their seats like Pedro Camacho, and when Genaro Jr. steals him away to pound out serials in Peru, he thinks he has bought a bank. Ratings will soar through the roof! Ad revenue will shower down like rain!

When he arrives Camacho hardly resembles his towering reputation. He’s extremely short, big-nosed, bug-eyed, less than handsome, and has an offbeat penchant for dressing up as his characters: wigs, fake beards, dresses, the whole kit. But he writes melodrama that welds people to their radios.

Camacho boasts several personality quirks that make him difficult to work with, not least his Olympian self-superiority. He loves to hear himself talk: “He was one of those men who have no need of conversational partners: all they require is listeners.” When Camacho does listen, he usually hijacks the moment to opine on the nature of the world—specifically his grandiose understanding of it.

Mario is the only person on staff who actually befriends Camacho, but Camacho is ill-suited to take Mario under his writerly wing. He’s not so much a literary man as a biological machine for generating radio scripts. He doesn’t read literature and spends almost all of his waking hours either cranking out radio plays for multiple serials or directing and acting in them. As Mario recounts,

He wrote very quickly, typing with just his index fingers. I watched and couldn’t believe my eyes: he never stopped to search for a word or ponder an idea, not the slightest shadow of a doubt ever appeared in his fanatic, bulging little eyes. He gave the impression that he was writing out a fair copy of a text that he knew by heart, typing something that was being dictated to him. How was it possible, at the speed with which his little fingers flew over the keys, for him to be inventing the situations, the incidents, the dialogue of so many different stories for nine, ten hours a day? And yet it was possible: the scripts came pouring out of that tenacious head of his and those indefatigable hands one after the other, each of them exactly the right length, like strings of sausages out of a machine. Once a chapter was finished, he never made corrections in it or even read it over; he handed it to the secretary to have copies run off and immediately started in on the next one.

The papers flying out of Camacho’s oversized typewriter conjure the sensational, bizarre, and lurid, in stories that Vargas Llosa intersperses between the novel’s main narrative: Sergeant Lituma, the faithful and dedicated police officer, ordered to murder a nameless, senseless savage by his superiors; Father Seferino, a radical priest who ministers to the poor and is determined to reverse the church’s prohibitions on masturbation and wife-swapping; Don Federico Téllez Unzátegui, turned zealous for rodent extermination after his infant daughter is eaten by rats, who develops his monomaniacal mission into a successful business only for his resentful family to turn on him; Lucho Abril Marroquín, a man who is psychologically crippled after hitting a child with his automobile, magically cured by obsessing on the cruelties of children and inflicting petty harassment on them; and many more—each story more outlandish than the one before.

But most outlandish of all? The story at the center of the novel, the love affair of Mario and Julia, his aunt-by-marriage, fourteen years his senior, recently divorced and in town to romantically recuperate and hopefully find a new husband.

The two start off with some minor if jocular antagonism, but Mario surprises himself as much as Julia when he steals a kiss at a family celebration. Good sense attempts to steer the couple back to reason, but the heart desires what the mind can only justify after the fact.

Mario and Julia clandestinely play around the edges of a relationship, knowing they’ll face trouble if the family finds out. But Julia continues to entertain other suitors. Vying for Julia’s affection, the men drive Mario to jealousy, which drives him to act. As his ardor amplifies, so does his commitment to Julia; he suggests they marry. Julia at first refuses but then relents. And that’s when it all goes bonkers—not just for Mario. Pedro Camacho begins losing his mind.

“Something embarrassing is happening to me these days,” Camacho reluctantly tells Mario. As the audience demands fresh episodes of their favorite serials, Camacho dutifully cranks them out—except little details begin betraying bigger problems. Characters start getting mixed up between the storylines. The nonstop production catches up.

“My head is a boiling volcano of ideas,” says Camacho. “It’s my memory that’s treacherous. That business about the names. . . . I’m not the one who’s mixing them up; they’re getting mixed up all by themselves. And when I realize what’s going on, it’s too late. I have to perform a juggling act to get them back in their proper places, to invent all sorts of clever reasons to account for all the shifting around.”

At first audiences love it. The Genaros think it’s brilliant. But Camacho can’t keep it all straight. Instead, he starts killing off the characters, trying to end storylines entirely to save himself the trouble of making sense of the tangled plot lines. But then dead characters from one story reappear in another without explanation. Half the fun for the reader is trying to keep up.

Finally, the crisis comes to a head and a shrink intervenes. “His psyche is undergoing a process of deliquescence,” says Genaro Jr., repeating the doctor’s diagnosis. “Do you understand what he means by that? That his mind is falling to pieces. . . .” They haul Camacho off to the funny farm.

Meanwhile, Mario’s affair with Aunt Julia progresses bumpily toward the altar—or at least the mayor’s record book. The two can’t be married in the church because Julia’s a divorcee, and Mario can’t be married at all because he’s underage. Managing the paperwork and chicanery required to pull it off would have outmatched even Camacho’s storytelling abilities to recount, but Vargas Llosa outdoes his own creation.

In part, that’s because he lived it. It’s there in the names. Mario Vargas Llosa is the Mario of the story, and Julia is real too. “At the age of 19, Mr. Vargas Llosa eloped with Julia Urquidi Illanes, his uncle’s sister-in-law, who was 29,” notes Simon Romero in Vargas Llosa’s New York Times obituary. Even Camacho is based on a real figure—Raul Salmon, a playwright Vargas Llosa knew—though Salmon rejected the characterization. When, for instance, an interviewer asked about the connection, “Raul Salmon’s face flushed and his smiling face turned cold.” Who could blame him?

The semi-autobiographical episodes captured in Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter form early installments in the long and storied literary and public life of Vargas Llosa, which spanned 89 years as something of a soap opera of its own. But you don’t need to know the backstory to appreciate the novel: a perfect comic picture of how life gets scrambled and how we cope when we can’t quite sort out the pieces.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

How wonderful to remember this novel! that was such an enjoyable experience for me decades ago. but then I heard about

Julia Urquidi Illanes own memoir, published in 1983, titled Lo que Varguitas no dijo (What Little Vargas Didn't Say) And realized as I have many many times that stories have many angles like light going through a prism they depend upon which side and base they meet to determine the colors that will emerge

Great novel! Read it many years ago. I'll have to put it on this year's to-be-read list. If you have a lot of time, read The War of the End of the World by Vargas Llosa. It's long and dense, but worth it.