Whatever Happened to the Semicolon?

Why Punctuation Is Less About Rules and More About Economics

Wander into a Gen Z or Alpha group chat and you might struggle to find your way back out again. I’m not talking about the fun but foreign slang. I’m talking about the nonstandard grammar, missing capitalization, and sentence fragments. And punctuation? Forget about it, except maybe em dashes—and watch out for those.

Is this terrible? A crisis? A loss?

The Marketplace of Meaning

Language works like a marketplace: not static, not preordained, but shaped by participation. It’s a responsive system with inputs and outputs constantly feeding one another. When people speak or write, their expressions become signals to the linguistic market, nudging the norms and expectations the rest of us respond to.

Take punctuation. Moses didn’t descend Sinai with a semicolon or an em dash. For centuries, writing muddled through with little to no punctuation. But as scribes and readers stumbled and strained over ambiguities, they conjured marks to clarify meaning—dots and strokes for the eyes and ears. Importantly, these uses didn’t follow a rulebook; they became the rulebook. Usage preceded systematization. And that process never stopped. Why would it? Why should it?

Norms coalesce, but as linguist John McWhorter would say, they’re always on the move, always provisional. When someone drops punctuation in a text message or swaps an em dash for a comma, they’re not just deviating from a norm (heaven forfend); they’re participating in a system none of us invented or controls but which all of us use and shape. Like it or not, their output becomes the next input.

This makes punctuation an emergent phenomenon. Like price in an economy, it reflects an equilibrium between writerly intention and readerly expectation. But like price, it doesn’t merely reflect the system—it affects it too. Every price is an implicit negotiation. When you spot a well-placed colon or encounter a conspicuous omission, you make decisions: accept, reject, repeat? And your choices, made consciously or not, loop back into the system.

This is how norms emerge: through bazillions of tiny, largely unnoticed transactions. Some will stabilize into conventions, but nothing’s fixed. “Correct” is code for whatever’s most common today. Because the system is responsive, common “correct” uses become self-reinforcing, but that doesn’t mean they’re static. Nothing is. Since every output is also an input, change is constant—even if we don’t spot the churn right away.

“Bad” punctuation sometimes carries real costs: befuddling communication, botched contracts, brand confusion, PR disasters, even courtroom losses. But most of the time the stakes are low and mistakes don’t much matter. Consequently, usage sways and drifts, and no one really notices. Then one day you look up and realize the rules have changed.

Let’s Talk Semicolons

“The semicolon seems to be in terminal decline, with its usage in English books plummeting by almost half in two decades,” according to a study cited by the Guardian, “from one appearing in every 205 words in 2000 to one use in every 390 words today.”

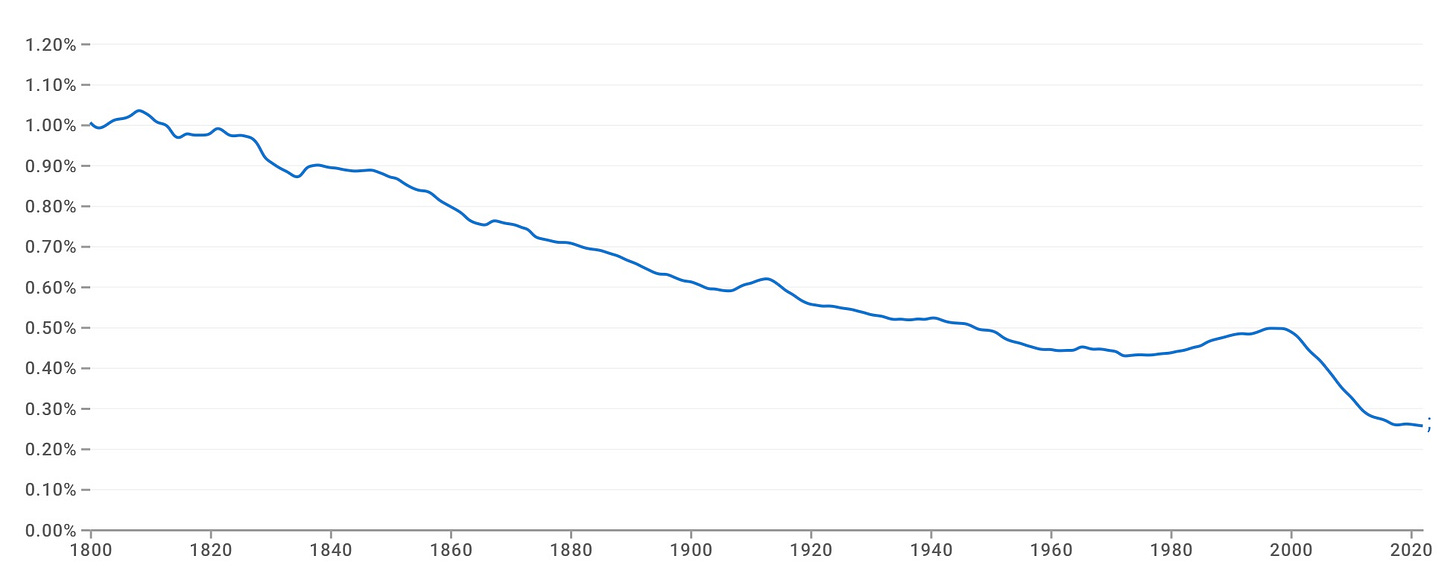

Expand the historical scope and the trend line is even more dramatic. In the early nineteenth century, the semicolon was everywhere. You couldn’t read a page without tripping over one—or several. Around 1800, the semicolon tallied roughly 1 percent of all printed words, according to a search on Google NGram. That’s one comma with a hat for every hundred words.

But over the decades, the semicolon beat a slow retreat; as prose evolved toward tighter, more efficient forms, its role declined. By the mid-nineteenth century, usage had already slipped below 0.9 percent. Through the late 1800s and into the twentieth century, the decline continued steadily. By 1960, it hovered just above 0.4 percent, a shadow of its former self.

There was a bump. From the 1980s to the early 2000s, the semicolon mounted a minor comeback; charge! But the revival proved short-lived. After the turn of the millennium, semicolon usage stumbled again, rolling down a steep slope that led it to its present, pathetic status: barely over 0.2 percent by 2022. When Kurt Vonnegut warned people off the semicolon in his 2005 book, A Man Without a Country, it was already tumbling downward to historic lows. He needn’t have feared.

Or bothered. But is that right?

This decline doesn’t mean semicolons are less valuable per se; you’ll note I use them all the time. (Watch your back, Herman Melville!) But their relative value in the marketplace of meaning has declined. Today they’re as popular as fat neckties—heck, as any neckties.

Of course, as a participant in the marketplace of meaning, my use of the semicolon matters, even if only marginally, and same with Vonnegut’s disdain for it. There was that bump in the Reagan–Clinton years; who’s to say it won’t happen again? Anything is possible, usually for unpredictable reasons—which brings me back to Gen Z and Gen Alpha.

Technological Factors

Gen Z loves them some em dashes. But some have started to tone down their use because em dashes are now viewed as telltale signs of AI-generated writing. Predictably, that backlash has triggered a counter-backlash; the idea that an em dash means a bot penned your piece is bonkers. So writers have begun reclaiming their beloved em dash (“you can have it when you pry it from my cold, dead fingers”). Others are using the moment to discuss deeper trends. A punctuation mark has become a hotbed of cultural negotiation: It’s not Israel or Iran, but duck!

As we’ve seen this is how the system moves: outputs, inputs, corrections, affirmations, and reinventions. But do we think about the role our technology plays in all of those steps? Even the strangest of outliers can influence the system. James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake has been mined for its bizarre punctuation patterns—useful in training AI models to mimic human unpredictability.

And AI isn’t just learning from us. It’s also shaping us. In one experiment, different chatbots produced noticeably different responses based on how a user punctuated their prompts. Punctuation shaped tone, voice, and output—which, naturally, nudge subsequent inputs.

Of course, other technological factors besides AI also shape our usage. The iPhone decimated punctuation and capitalization in our texts, not out of laziness but out of user interface design. The Apple iOS keyboard made them marginally difficult to employ. In rapid exchanges, that little bit of extra effort wasn’t worth the time or trouble, and people adapt: They drop what feels unnecessary. The medium alters the message. But weird stuff still happens.

Exclamatory Comeback!

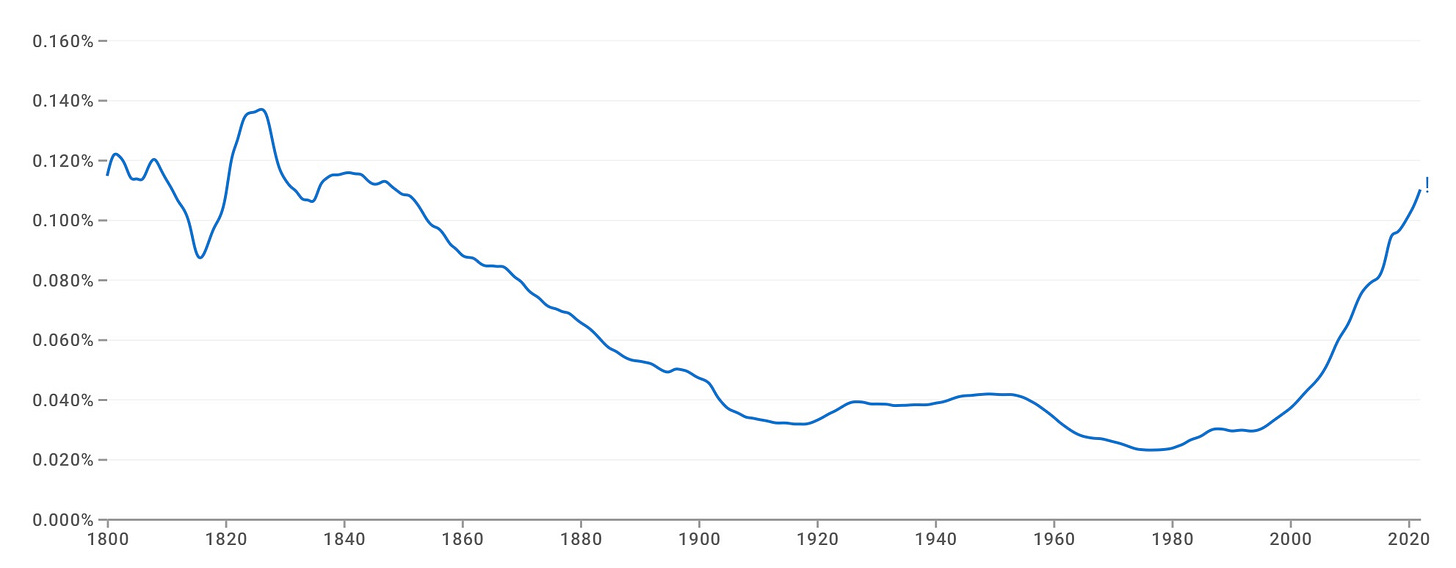

In the twentieth century, teachers and writing authorities of whatever type discouraged the exclamation mark. Editors stared down yards of nose to revile its undisciplined spunk. It was juvenile, overenthusiastic, unserious. But don’t look now: The leprous mark is back! It’s everywhere—not just tolerated but expected in casual writing like texts, emails, and Slack messages.

Why? As we’ve seen, it’s mimetic. You see one, you use one—at least some will do so, and over time a new norm replaces the old. Google NGram charts the dramatic upswing.

The meaning of punctuation in various contexts evolves over time for a variety of interrelated reasons. Who would have predicted that a period would be considered passive aggressive, or even hostile? But that’s the case in text messages, especially among Gen Z and Gen Alpha users—and now even emails as the usage has drifted. It turns out that the extra effort required to end on a period feels to some users like putting your foot down.

It carries unintentional gravity. It’s cold, maybe mean. “In text especially, I feel like [periods] are firm or angry,” explains one university student. “If someone says, ‘Yeah, okay period.’ It’s like my blood pressure is through the roof, and my heart is racing. Or even the word ‘fine,’ fine with no period; no problem. But if someone says fine with a period . . . someone is in trouble.”

In the two-dimensional space of a screen, devoid of body language and facial expressions, you need something else if you want to signal warmth, welcoming, and enthusiasm. So, counterintuitively, an exclamation mark now communicates something softer than a period. Go figure. But that mimetic, emergent quality of usage and norms comes from real humans affected by the words they read.

This market-like quality of language creates a funny circularity. What does it take for a new trend to take off? It’ll never happen unless it happens. That applies to anyone hoping to redeem the semicolon (man, it’s lonely here), and it also applies to folks hoping to resurrect more novel forms of punctuation. If you really want the interrobang (that’s this fella, ‽), you’d better start using it and somehow convince all your friends.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below, 💬 in the comments, and share it with a friend!

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe. It’s free, and all the cool kids are doing it.

And don’t miss this:

An enjoyable read! I have often call myself a semi-colon fool when editing my own work but i am Gen X! What do you think about the phonetic respelling of words? I have seen 'interested' respelled as 'inch rested'. A part of me wants to draw the line there, but I agree with what you said that language is formed by its participation.

Also, I can't help but think 'inch rested', as slang, must have been intended for another meaning - and should - and it just got confused.

What happens when mistakes become norms due to popular use? Like 'irregardless'? :O

Save the semicolon! "Em dashes are now viewed as telltale signs of AI-generated writing." And you know why? I've always been fond of them. And Google AI's hoovered up five of my novels from pirate book sites—to teach them how to write. Never asked permission—never paid me a nickel. Watch... they'll go after alliteration next. Got some in my books... along with ellipses. I always liked me a little alliteration.

Good one, Joel.