Go on, Try It; The Semicolon Isn’t as Scary as You Think

Reviewing Cecelia Watson’s ‘Semicolon.’ Yes, It’s Really About Punctuation. You’ll Either Love It or Hate It; People Have Opinions

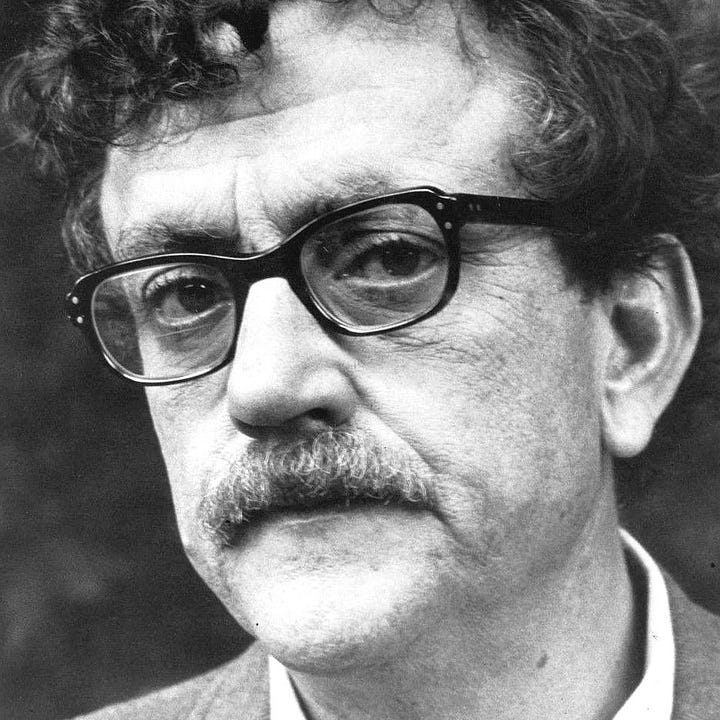

The first tip I ever received about semicolons? Avoid all use. My friendly adviser had read novelist Kurt Vonnegut’s dictum: “Do not use semicolons. . . . All they do is show you’ve been to college.”

As a professional editor, I’ve heard other editors say as much. I’ve also heard plenty of writers ask me if it’s okay to use them: “I’ve heard you’re not supposed to.” Cormac McCarthy certainly disapproved.

But if we’re honest, the real reason people hedge on semicolons is they’re terrified of misuse and being judged. Depending on what guide you consult, there are a handful of rules, running to dozens. And most of them require more mastery of grammar than the average bootstrapping writer possesses. “Dependent clause? I’m just trying to say [fill in the blank].”

Throw some internet into the mix and all bets are off about usage, proper or otherwise. It’s safer to opt for something else—usually a dash.

Dashing to an Easy Solution

This meme, first tweeted by Clare Costello in 2018, has been liked more than 170,000 times. It has as many fans as Santa Rosa, California, has residents—and that’s not just because zoning restrictions have priced everyone out of the market.

We love the dash because it comes with almost no zoning rules of its own. You can pretty much use it whenever and however feeling, style, and aesthetics lead. Chat with editors and I bet they’ll tell you: The only time they interfere with an author’s dashes is when they clutter the page or break the flow of thought.

No surprise then, says Cecelia Watson of Bard College, “We now live in the Era of the Dash.” But not so fast.

Is the semicolon really that scary? It’s just a comma with a dot perched overhead. And how serious are all those rules; are they real; are jail terms attached? What if we just told everyone to calm the flip down, breathe into a paper bag, and consider how we got here? That’s exactly what Watson does in her book, Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark.

On Your Mark!

Watson starts by surveying the general ambivalence, even animosity, people feel toward the semicolon. It’s not just Vonnegut and McCarthy; it turns out many writers get spicy about semicolons. Why?

To help answer, Watson takes us back to the beginning. Where did the semicolon come from? Italian humanists began tinkering with the mark in the late fifteenth century. From there it was swept aloft by the tides of the Renaissance and the burgeoning printing industry.

So, start there: Italy. If you’re partial to its wine, painters, designers, cuisine, romance, sports cars, leather, and all the rest, why not its punctuation? Pour a glass; with a semicolon. Easy.

Alas, the difficulty sets in as the centuries progress. Now that we have this mark, how should we wield it? Early on, punctuation was meant to capture the rhythms and cadence of spoken language. Want to indicate a pause but not the completion of the thought? Drop in a comma. In the mood for a longer pause? Try the colon. Want something in between? You guessed it!

But as people grew enamored of science in the nineteenth century, they wanted their language to reflect a more serious and systematic approach.

One of Watson’s many amusing chapters concerns the surge in English grammar guides during this period—along with the catty infighting of their authors, each convinced of their special one true way. Thanks for teaching us how to diagram sentences, fellas; we’ve all had hangups ever since.

And for what? The systemization didn’t really work all that well. As Watson says,

The rules couldn’t shift, while usage inevitably did. . . . Whenever grammarians tried to pin down punctuation marks with rules, they inevitably slipped their restraints, no matter whether they were shackled with a few broad rules or a hundred narrow ones.

Granted, some persnicketiness is warranted. Watson presents stories of laws, even a death sentence, where enforcement came down to the interpretation of semicolons or their lack. But usually the rules are secondary to style and effect. That goes for writers of all kinds—whatever Vonnegut’s concerns about pretension.

And let’s knock that one out of the way while we’re here. Writing at Quora, Eva Silvertant shared a quick, though incomplete, survey of Vonnegut’s works. A few books on the list are utterly devoid, but semicolons do appear in most. According to another study, this one by Ben Blatt:

Vonnegut averages less than 30 semicolons per novel. That’s about one every 10 pages. To be precise, for every 100,000 words Vonnegut writes, he used 41 semicolons.

That’s not many. But it’s not never, which makes Vonnegut the same as the rest of us who can’t follow our own advice. Then again, why would he?

Different Strokes for Different Folks

Why would Vonnegut stoop to employ a mark he disdained? Because a semicolon is—for all the angst and anger it evokes—sometimes exactly the right mark to do what the writer desires. (That, and he was probably kidding.)

Watson presents several cases of authors using semicolons to weave their various spells: Herman Melville, Rebecca Solnit, Irvine Welsh, and others.

An interesting case: Raymond Chandler, whose personal letters and essays make ready use of semicolons, rarely used them in his Philip Marlowe detective novels. Watson finds just two in The Big Sleep and a single example in The High Window. But Chandler was up to something here, and it’s not averting the slur of snobbery.

In these first-person narratives, scant semicolons serve a literary purpose, showing how little personal reflection the hard-boiled detective entertains. Marlowe presses on without slowing, save that rare moment when Chandler wants to pump the brakes; in goes a semicolon.

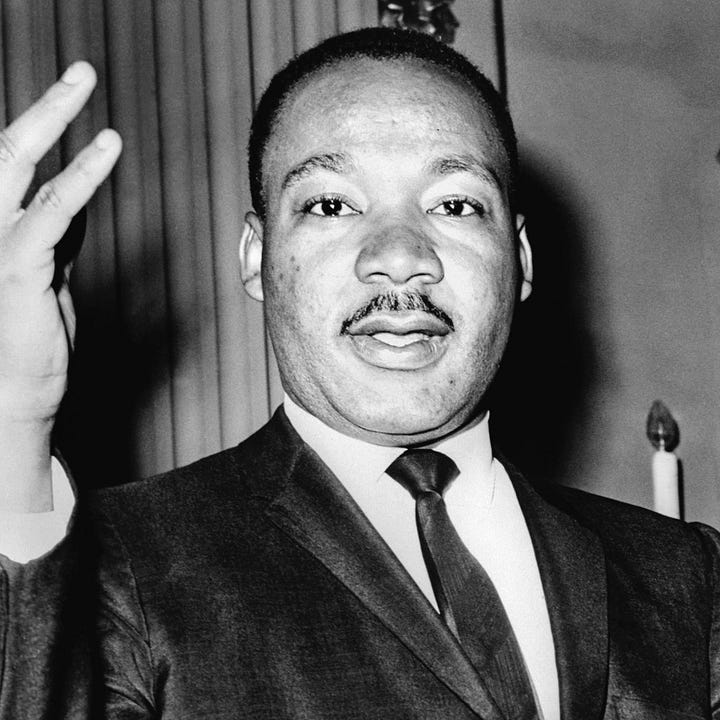

Used by other writers, the speed effect can be reversed. In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. uses semicolons throughout, including one passage highlighted by Watson. Told he’s impatient, King reminds his detractors why.

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when . . . ; when . . . ; when . . . ; when . . . ; when . . . ; when . . . ; when . . . ; when . . . ; then . . . .

King wields the semicolon nine times in this one passage, and the effect hits home even when abridged. He eventually comes to his conclusion—“then”—but not until he’s added clause after clause, each one staple-gunned to the last with a semicolon.

King piles up offenses, indignities, outrages, stringing out his audience’s attention like a musician striking discordant notes, refusing the resolution until the full effect is achieved. The technique lends momentum to the paragraph, pulling the reader along uncomfortably to the end—the only hope of resolving the mounting tension.

Nothing egg-heady about that. Just the passionate prose of an imprisoned man who won’t let you sit still until you see it his way. And the only tool he’s got are words and the underappreciated methods that turn them into messages.

Chandler, as Watson points out, achieved a similar effect with a string of “ifs” joined by semicolons in a piece for The Atlantic. While less important than King’s use, “Oscar Night in Hollywood” nonetheless shows how flexible and powerful the semicolon can be.

Rules Aren’t Writing

What emerges from Watson’s historical and literary exploration is an appreciation for the art of punctuation over the supposed science, which has always been somewhat arbitrary and after-the-fact, never really able to keep up with developments.

That might make some of us uneasy. But why? Rules are useful. Watson suggests that the constraints they impose might actually spur creativity—same as how rhythmic schemes or characterization shapes a poem or novel. But we should never confuse rules with writing any more than we confuse recipes with cooking, building codes with homes, and rubrics with worship.

Rules aren’t the point. And while they usually serve it, they can sometimes also thwart it.

Rules can be valuable; they can be helpful. But in my experience good writing comes from reading and appreciating good writing. If there’s an overlap with college, it’s reading (to the extent they still do that there). Appreciation is mimetic. We see how Vonnegut or Chandler use the few they employ and ask, “What’s that doing there? What effect is that supposed to have?” We see how another, such as Melville, sprinkles them over his pages with a salt shaker.

If it works, you’ll know it. You’ll recognize and feel it—whether it follows the rules or not. Now you’ve got something you can experiment with yourself. This is, by the way, how all language evolves and adapts. We try new things. Some of it works; some doesn’t. Either way, the world still turns.

If that fails to convince, remember Italy; remember the wine; remember the music! Nobody is that uptight in a gondola.

Here’s my challenge to you: What if the semicolon were no more frightening than the dash? Once you get to know it, the semicolon is every bit as flexible and forgiving. Go on; try it; try it today! I dare you.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Before you go . . .

The fact that I chose to read this article at 7 on a Saturday morning must say something about my love of punctuation and your ability to capture a reader's attention! I love semicolons; I wish I felt more confident in using them.

Came across more evidence that Vonnegut did not follow his own advice:

"When Hemingway killed himself he put a period at the end of his life; old age is more like a semicolon."

I don't think I've ever seen so many semicolons, colons, and dashes in one essay before. Very clever!