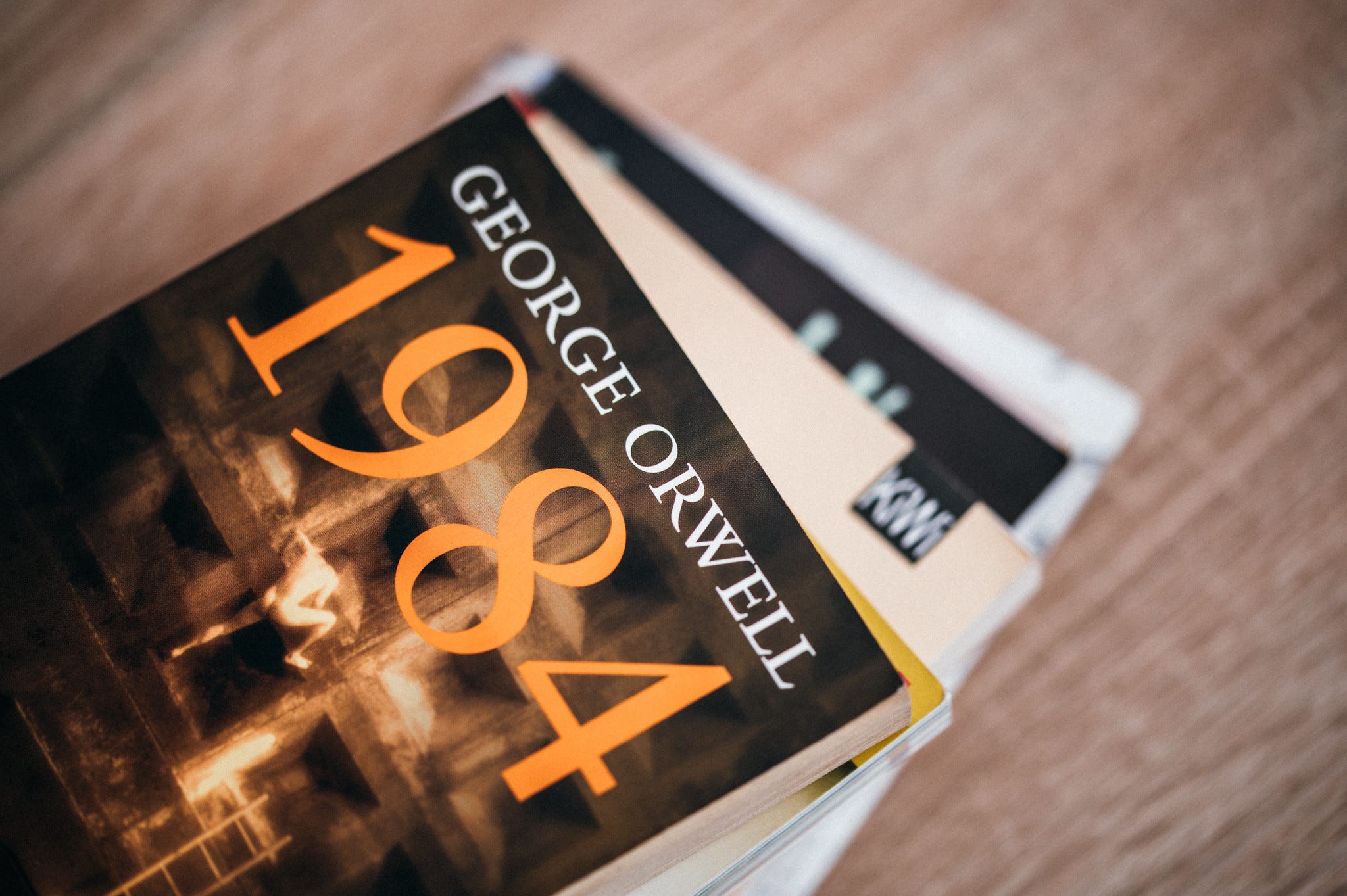

What Orwell’s ‘1984’ Reveals About the Threat of AI

Orwell’s Nightmare Wasn’t About Technology; It Was About Who Controls It

When one thinks of the risks posed by a large-scale information and behavioral management system that engages in surveillance, lies, and the revision of history, it’s hard not to think of 1984.

“What we’re really talking about is ‘Orwellian AI,’” said David Sacks, chair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, discussing the risks posed by artificial intelligence on a recent podcast. “We’re talking about AI that lies to you, that distorts an answer, that rewrites history in real time to serve a current political agenda of the people who are in power.” He added that “to me, this is the biggest risk of AI. . . . It’s not The Terminator, it’s 1984.” In a post on X, Elon Musk quoted the post citing Sacks’ words and commented “True.”

How “Orwellian” is the threat posed by AI? What can we learn from 1984 about it?

Technology as Amplifier

It’s true, of course, that the novel sounds a warning about the risks posed to human freedom by the misuse of technology to sacrifice truth—even at the level of 2+2=4—to the demands of power via censorship and a constant barrage of propaganda, backed up by the threat of violence. But the massive damage done to privacy and to the capacity for original thinking, art, dissent, and the discernment of truth in 1984 is at the hands of a lawless one-party state possessed merely of radio, two-way televisions, posters, and some not especially awe-inspiring 1940s office equipment.

The threat seems to be much the same as the one we face today, albeit on a different scale, and thus one might infer that AI would exacerbate existing intellectual, moral, and cultural threats, rather than giving rise to new ones.

Orwell was already aware that without legal safeguards, technology, bureaucracy, and psychology could be fused and weaponized to undo civilization. We see the effects of this fusion in Oceania. And this is the imagined product of a clunky, analog system that depends in part upon the reports of small children who listen in on their parents while the latter sleep, and that uses torture as a built-in, mop-up technique when the rest of the system fails. Just imagine how bad it would be if the system were controlled by computerization, algorithms, data mining, and digital surveillance, as it would be today.

Civilizational Risk

What might Orwell have deemed to be most urgent about the risks of AI? Here, it is useful to remember that Orwell’s architecture of civilizational risk was technologically deterministic. The technology that he was most concerned about at the level of geopolitics was the atomic bomb. He treats nuclear fission as being simply a weapon. And to a considerable extent, he accepted the “commonplace that the history of civilizations is largely the history of weapons.” He argued that “the ages in which the dominant weapon is expensive or difficult to make will tend to be ages of despotism, whereas when the dominant weapon is cheap and simple, the common people have a chance.” Thus, for him, bombs enslave while the musket or the rifle “gives claws to the weak.”

The world of 1984 is the atomic world writ large, where the only three existing superstates are in a state of permanent, limited war with one another. But within the state of Oceania, the technology that Orwell is most concerned about is nothing nuclear (in the domestic context, that might have meant talking about the potential for cheap electricity or other benefits) but rather language, which he treats as a technology that has multiple uses.

For Orwell, language, when used well, could allow for redemptive contact with reality. It could unlock memory, convey truth, and amount to a defense of the human heritage and of freedom.

The exemplary use of language is found in the passage in which Winston Smith, the protagonist of the novel, engages in a private act of writing in his notebook, which is cast along dramatic and, at points, heroic lines:

The thing that he was about to do was to open a diary. This was not illegal (nothing was illegal, since there were no longer any laws), but if detected it was reasonably certain that it would be punished by death, or at least by twenty-five years in a forced-labour camp. . . . The pen was an archaic instrument, seldom used even for signatures, and he had procured one, furtively and with some difficulty, simply because of a feeling that the beautiful creamy paper deserved to be written on with a real nib instead of being scratched with an ink-pencil. . . . He dipped the pen into the ink and then faltered for just a second. . . . To mark the paper was the decisive act. In small clumsy letters he wrote: April 4th, 1984.

This is writing as a means of rebellious assertion of the human capacity to defy the fear of death and punishment for the sake of positing for the moment, or decreeing for all time, the existence of a fact. But, in fact, the date in question is not a fact at all, as Winston does not know what day it is, thanks to the state’s manipulation of basic information.

Language as a Dual-Use Technology

In 1984 the state uses language to induce detachment from reality, blur the difference between lies and truth, and prevent the perception of alternative ways of thinking. The central mechanism of its vast regulatory and administrative system is Newspeak, the purpose of which “was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc but to make all other modes of thought impossible.”

Writing and speech are merged in the context of an information storage and distortion technology, in which single lies—such as “Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia”—stand in for a more pervasive substrate of untruth. The lie spreads from the single-party government that devises it to others via acceptance, as registered in false written records.

For most intents and purposes, the lie replaces the truth, apart from silent questions and doubts in people’s minds that must never be fully formulated even as thoughts much less words: “And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed—if all records told the same tale—then the lie passed into history and became truth.” The Party’s apparatus converts the truth into the lie and the written lie, in turn, becomes the official truth, since no evidence exists apart from the tale told in writing.

Orwell made no argument that language—the ultimate technology of power—could be purged of its capacity to be used for propaganda, but he tried to use his writings to show that language could also counter lying words and fake history. Varying mixtures of same twenty-six letters in the English alphabet could serve truth and allow for creativity or serve the agenda of those in power and cement political orthodoxy at any given time.

The Propagandist’s Dilemma

Orwell was himself a propagandist for the BBC from August 1941–November 1943. And 1984 was in some sense, a test of whether he could write his way out of that experience, back to the other side of language, as it were. As a user and lover of language, Orwell knew its potential for good and ill. But his sense of having bitten the apple was such that he came to see the taint in professional writing wherever he looked. In his diary in 1942, it appears that no writer is good—no, no not one, but that he must nonetheless be good or at least clear-sighted about his badness in spite of this:

We are all drowning in filth. When I talk to anyone or read the writings of anyone who has an axe to grind, I feel that intellectual honesty and balanced judgment have simply disappeared from the face of the earth. Everyone’s thought is forensic, everyone is simply putting a “case” with deliberate suppression of his opponent’s point of view, and, what is more, with complete insensitiveness to any sufferings except those of himself and his friends. . . . But is there no one who has both firm opinions and a balanced outlook? Actually there are plenty, but they are powerless. All power is in the hands of paranoiacs.

As we think about the risks of yet another dual-use technology, reading Orwell should invite us to ask whether and how we believe that power may be used well and by whom. Can those who generate and wield technological power, as distinguished from those who seek to police them, possibly use power well? Or is creation and expression through writing so dangerous that the monitors and the creators must be fused into one machine, against which Winston’s lonely act of writing has no chance.

The question is if we are already in a world like that of 1984, in which there are no options, and in which all nuclear states, by virtue of being nuclear, are bound to use language for pathological ends with impunity. Orwell thought that possession of the bomb would give rise to oligarchical collectivism, in which, ultimately, two superstates would be comprised mostly of slaves ruled by an elite which controls the technology. For him, these states would be morally and politically indistinct, whatever their professed principles.

The members of the Inner Party in 1984 do not even profess to be animated by a concern for the common good. Rather, O’Brien, speaking for the party, claims to want power for the sake of power. In the moral world of the novel, it seems that he is telling the truth. One implication of this is that we should be concerned when the lying stops. But, in our own time, it hasn’t stopped yet.

The West’s AI Gamble

What we have are two very different systems of government, both flawed, competing for dominance with respect to AI. One will win. We should ask ourselves whether we believe that a commitment to the Bill of Rights, the practice of representative government, and democratic culture makes any difference with respect to the capacity to develop and use AI well. If it doesn’t, and only a technologically-enabled, centralized bureaucratic apparatus of superintendence and censorship holds out hope for the right use of power, then the West will lose whatever distinguishing properties it still has left.

Nothing could be more Western than the idea that power must be broken up and that powers, once splintered, may be used to counteract powers. For Orwell, the power of literary writing could be used to counteract the power of propaganda, but the power unleashed through democratic, representative, rights-based government could not counteract the power released by nuclear fission. 1984 reflects his cynicism concerning the beneficial generation and use of power in politics, applied nuclear physics, and engineering, and his idealism concerning literature.

The question becomes: Is AI more like the atom bomb (where Orwell saw no escape) or more like language (where he thought redemptive use remained possible)?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

And tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future.

I think this is a sophisticated take on why '1984' is not just a metaphor for surveillance. You have correctly identified language as the true 'technology of power' Orwell feared.

To sharpen this, the most immediate 'Orwellian' threat from Large Language Models (LLMs) is their capacity to mass-produce Newspeak and rewrite history in real-time. Where the Ministry of Truth needed thousands of clerks, an AI can execute the 'Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia' directive instantly and globally.

I agree an important aspect that you discuss is the elite's use of power, it’s worth recalling the proles in 1984. Their control wasn't through constant ideological struggle, but through indifference and mass-produced, simple entertainment (prolefeed). Today, AI-driven algorithms and content farms are perfectly suited to create this kind of distracting, overwhelming, and intellectually vapid 'filth', ensuring that the masses are too distracted and confused to even attempt Winston’s 'heroic act' of writing the truth.

The question becomes: Is AI-generated language a tool for the individual to counter propaganda, or is its inherent speed and scale an insurmountable force that dissolves the human capacity for independent thought and redemptive writing?

This was a very good and solid 'splainer. Thank you for covering GO's critical understanding of the impact of language ⏳✍🏼📚 and the manipulation 📰✂️🗑️ thereof on a society. Our public/ staterun education🙋🏻♂️🤦🏼♀️🤷🏻 / school 'system' 👨🏼🏫 has managed to dumb down almost two full generations of students, completely kicking open the doors for NEWSPEAK, yah know, like uhm, it's so totally💅🏻 amazing.....!

Lord, have mercy.

Grace and peace to you, one day at a time....