We Almost Lost the Statue of Liberty, and Other Misadventures in Maintenance

Reviewing Stewart Brand’s ‘Maintenance: Of Everything, Part One’

The Statue of Liberty almost fell apart. The 150-foot statue, designed by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, was composed of a 62,000-pound copper shell draped over a massive wrought-iron skeleton. Gustave Eiffel, who engineered the structure, recognized the danger: iron can’t touch copper without corroding.

The best solution he could conceive in 1886? Insulating the contact points with asbestos coated in shellac. It worked brilliantly—until the asbestos began soaking up salt water and accelerating the corrosion instead of holding it at bay. Rust ran rampant.

By 1981, half the iron structure holding the old girl up showed signs of corrosion. As many as a third of the rivets holding her together were loose, degraded, or gone. And parts, including the upraised arm, threatened to fall.

“When you take responsibility for something,” says Stewart Brand in his book, Maintenance: Of Everything, Part One, “you enter into a contract to take care of it. If it’s a child, to keep it fed. If it’s a knife, to keep it sharp.”

And if it’s a beacon of freedom, hope, and the republican virtue of self-governance? You replace the rusted bits with 76,000 pounds of stainless steel and insulate the contact points with Teflon. And preferably, you do so before the problem becomes a national embarrassment.

As Brand shows, that crisis was narrowly averted after a heroic repair effort, necessary because the various federal departments tasked with maintenance didn’t want the job and kept foisting it onto the next available pigeon. And here’s the crux of the whole problem—not only with Statue of Liberty, but pretty much all of life—maintenance is essential, and nobody enjoys doing it.

More problematic, as Brand says: it’s usually optional. That means you can put it off indefinitely. And suddenly I think I’m reading an indictment of my own behavior. How did he know?!

3 Approaches to Maintenance

“Probably a great many famous stories could be told in terms of maintenance,” says Brand at the start of chapter 1. Indeed, the book brims with such stories, all of them fascinating.

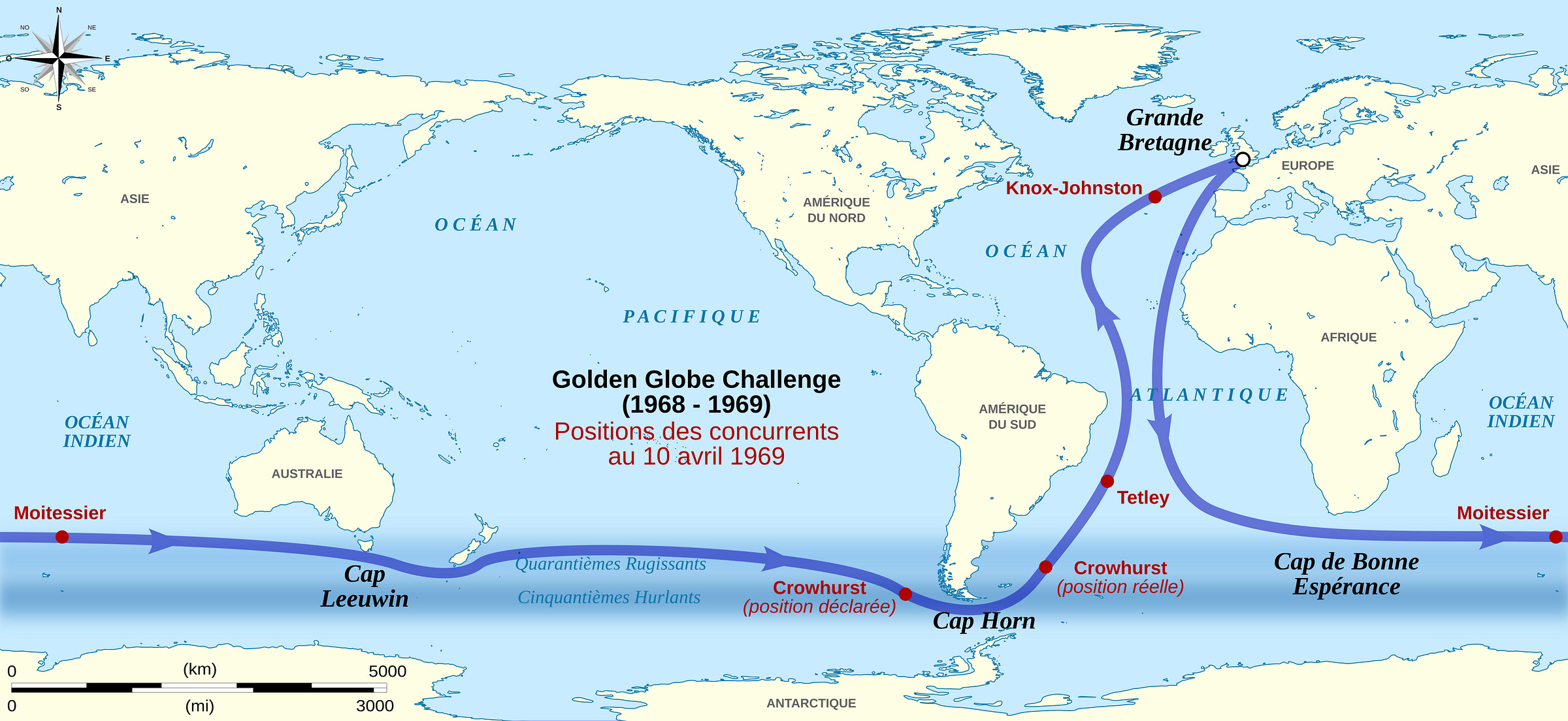

The book opens with a solo sailboat race. Nine men set out from Britain in 1968 on a 30,000 mile journey around the globe—each man in their own boat, each man disallowed by race rules to go ashore, resupply, or anything. The test was to see who could beat the elements—and the clock—entirely on their own. Each man equipped their vessel as they saw fit and set sail.

Brand sees the accounts of three particular competitors as indicative of different approaches to maintenance, which he defines as “the whole grand process of keeping a thing going.” On the open seas in treacherous conditions that grand process was a constant.

Robin Knox-Johnston discovered, for instance, a substantial leak in his hull not long after departure. The leak occurred several feet below the waterline, and Knox-Johnston had to dive, inspect the problem, puzzle out a solution, then implement the fix. He also had to skedaddle out of the water and shoot a shark with his rifle before he could finish the job. All in a day’s work.

The constant repairs helped him keep his wits on the long solitary voyage. “The only way to overcome my present feeling of depression is to fully occupy myself,” said Knox-Johnston, “so I cleaned and served the remaining bottle screw threads and then gave all the servings a coat of Stockholm Tar. Next I polished the vents and gave them a coating of boiled oil. Whilst I had it out I dabbed the oil on wire and rust patches.”

The second mariner, Donald Crowhurst, offers a more cautionary tale. He embarked unprepared and never quite recovered. His logs tell the story of a man out of his depth in most every meaningful way. He sailed an untested vessel, left critical equipment on the dock, and failed to prepare for predictable eventualities.

Hope, as my wife likes to say, is not a strategy.

Instead of honorably quitting the race as his hopes soured, Crowhurst decided to lie and bide his time in the Southern Atlantic, keeping a bogus log to record an imaginary version of the voyage that he initially thought would validate his win when he rejoined the race and beat the other contestants home. Nope. As his boat deteriorated, so did his sanity; keeping the divergent logs was more than his psyche could sustain. Crowhurst finally cracked and dove into the sea, never to surface again. “Poor preparation and maintenance led to Crowhurst’s cheat,” says Brand. “The cheat led to his death.”

Bernard Moitessier represents yet a third approach. Unlike Knox-Johnston who made do with the boat he had, Moitessier sailed in a ship optimized for the journey, one designed for resilience and minimal maintenance. He opted to strip out any unnecessary gear that could go squirrelly or multiply headaches. Crowhurst, for instance, did nothing but fiddle with and repair his two-way radio; Moitessier didn’t even take one. He was a minimalist half a century before the trend.

“Simplicity is,” he told an interviewer, “a form of beauty.” The more complexity within in a system, the more points of failure and the more maintenance it takes to keep it operable. Moitessier designed for maintenance by opting for simple technology and simple solutions.

He also advocated prompt repair. “My rule is,” he said, “a new boat every day.” Brand comments: “His years at sea had taught him that if you don’t fix something when you first see it beginning to fail, it’s very likely to finish failing just when it is most dangerous and the hardest to deal with. . . .” I tend to put off maintenance as long as possible. Moitessier would have kicked me off his boat.

Brand distills these three approaches as follows. Two worked well. One? Not so much.

Knox-Johnston’s style was: “Whatever comes, deal with it.” And he did.

Crowhurst’s was: “Hope for the best.” It killed him.

Moitessier’s was: “Prepare for the worst.” It freed him.

Who really won the race? I’ll leave that for Brand to tell you, and I suspect you’ll love to hear him tell it. Same with many other accounts in the book, including when Israel’s army bested Egypt in the field in 1973 largely because of what Brand calls a maintenance mind versus a neglect mind.

Maintenance Mind vs. Neglect Mind

The Israelis were far more adept at repairing their own equipment than their foes. In one engagement, for instance, the Israeli’s lost 40 tanks to enemy fire; they rapidly repaired and returned all but six to battle. They also captured and repaired tanks the Egyptian forces abandoned, adding some 3,000 enemy tanks to their own armaments over the war.

The story repeated itself in the early days of the ongoing Ukrainian–Russian war. Russian equipment routinely broke down, abandoned by Putin’s soldiers. The Ukrainian army recovered this equipment and put it back into service. “More than half of Ukraine’s 1,000-tank fleet was made up of battlefield donations from Russia,” says Brand. Amazingly, many of these vehicles weren’t even substantially damaged. The Russians simply had no sense of the equipment’s value or any responsibility to take care of it.

The Israelis and Ukrainians possessed a maintenance mind, whereas the Egyptians and Russians displayed a neglect mind. What constitutes these two ways of seeing the world? As I understand the argument, the primary differences come down to a sense of foresight, ownership, and agency.

While Brand avoids offering universal rules of maintenance, I think we can tease out several principles that generally apply to these two ways of seeing. See on what side of these statements you tend to fall. I already know how I come down, and I’m not proud of myself. In no particular order:

Entropy as baseline. The maintenance mind treats breakdown as normal, sees things as they actually behave over time, and plans for wear, aging, and decay, whereas the neglect mind indulges irrational optimism and acts surprised when things start breaking.

Stewardship as obligation. The maintenance mind owns long-term outcomes as a moral responsibility, whereas the neglect mind treats failure as aberration, defers consequences, and pushes responsibility onto others.

Craft over contempt. The maintenance mind understands upkeep as skilled work that confers competence, pride, and self-respect, whereas the neglect mind dismisses it as menial—beneath the attention of serious people.

Design for the long haul. The maintenance mind integrates design and upkeep—favoring simplicity, modularity, and interchangeable parts—whereas the neglect mind insulates creators from consequences and mistakes complexity for progress.

Learning through feedback. The maintenance mind adjusts through continuous information from problems as they manifest, whereas the neglect mind ignores signals that disrupt its plans or complicate its assumptions.

Authority at the point of failure. The maintenance mind confers agency on those closest to problems and trusts judgment formed through experience, whereas the neglect mind hoards permission at the top and prefers bureaucratic procedures that distance decision-makers from reality.

Brand’s Statue of Liberty story illustrates several of these principles at once. Start with No. 1, entropy as baseline: Eiffel’s asbestos-and-shellac solution was ingenious for 1886, but nobody planned for its eventual degradation. Salt water and time are predictable; the corrosion wasn’t a surprise. The surprise was institutional; everyone assumed someone else was watching.

Which points to No. 2, stewardship as obligation. The various federal departments tasked with the statue’s care didn’t want the job and kept putting it off. Nobody owned the problem. Failure became someone else’s concern, consequences deferred until deferral was no longer an option.

And then No. 6, authority at the point of failure. The neglect mind arises from unclear and diffused accountability—which is maybe the most common way it shows up in institutional settings. No villain, just a series of people saying “not my problem” until the arm nearly falls off.

The deeper irony? A monument to self-governance couldn’t govern its own upkeep. Where else are we seeing that happening?

Organizations and Individuals

These dueling sets of principles play out both in organizational and individual settings. On the organizational side, the maintenance mind favors bottom-up models over top-down command (think Israelis and Ukrainians). Neglect tends to flourish wherever decision-making is hoarded at the top, distant from the problems themselves (think Egyptians and Russians).

The maintenance mind emerges when those closest to failure are empowered to act—trusted with judgment, granted authority, held responsible for outcomes (again, Israelis and Ukrainians). Top-down systems discourage initiative at lower levels and thus breed neglect (again, Egyptians and Russians); as Brand shows, that’s a bad way to win a war. Or, for that matter, run a company.

On the individual side, the maintenance mind animates DIY culture, a can-do ethos, the person who actually reads the manual. Both my grandpas were fixers and could jury-rig any repair. “Read the destructions,” Grandpa Miller would joke. Today the instructional manual is probably a YouTube playlist, as Brand enthuses, but the principle applies. It’s the reluctance to outsource competence, the conviction that understanding how things go—and taking responsibility for keeping them going—is part of what it means to be a capable human.

The neglect mind, by contrast, throws things away rather than fixing them, calls professionals at the first indication of trouble rather than sit with the problem long enough to see if solutions present themselves, and treats mechanical or material knowledge as someone else’s domain (and problem). One mind builds skill and self-reliance; the other reinforces helplessness.

That isn’t to say you have to fix everything yourself, and Brand doesn’t suggest any such thing. But he does encourage us to see how these dueling mindsets operate in our lives and roll up our sleeves when we can or must.

Consider the three mariners. Their stories illustrate that the maintenance mind operates at multiple points—planning, design, and upkeep. Knox-Johnston and Moitessier emphasized different points in their maintenance, particular to their individual preferences and personality. But Crowhurst? Bad planning, bad design, bad upkeep. The dude was a walking advertisement for the neglect mind. Brand’s message is to get your hands dirty to whatever degree you want or need, but don’t be that guy.

‘Masters of Our Stuff’

As the title suggests, Brand conceives Maintenance: Of Everything, Part One as a series of books. I eagerly await future volumes. Part One covers everything from motorcycles and machine guns to service manuals and the magic of YouTube. It’s digressive, every section fully illustrated, and compulsively readable. And like many helpful books it causes the reader—caused me—to rethink not just the world, but ourselves—myself—as well.

In an exploration of Robert Pirsig’s bestselling Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Brand highlights several ways we sabotage ourselves when it comes to solving problems for ourselves. We refuse to rethink our assumptions and we succumb to ego, anxiety, impatience, and boredom. What would it mean for us—for me—to overcome those failings and become, as Matthew Crawford puts it, “masters of our stuff”?

Having developed a maintenance mind, we’d possibly become the kind of people that can solve bigger, more vexing problems. And that’s where Brand plans to take the series next.

Where do I preorder?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends—or your mechanic.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Make sure you check out this piece about Stewart Brand’s 1968 creation, The Whole Earth Catalog.

This sounds like the kind of book I'd love. SMBSLT. (So many books, so little time. . .) I liked the applications of the three mindsets to warfare, and that made sense. I try not to "spiritualize" things too much, but I was struck by "Stewardship as obligation. The maintenance mind owns long-term outcomes as a moral responsibility, whereas the neglect mind treats failure as aberration, defers consequences, and pushes responsibility onto others." What I've seen in the worst of Protestantism, the health-and-wealth sectors as well as those who define their Christianity as a vehicle to a comfortable lifestyle, is this. When severe trials do come, they see it as an aberration, even so much as an unfair imposition they didn't deserve. After all, they did "all the right things" and then their health craters or their families disintegrate. How dare God allow this, I've heard, when He could have prevented it at least. In this, they know where the buck stops and when He allows such things, He let them down. I hope I don't sound harsh, but I'm practically quoting from a ministry leader I know.

My father designed and built his own house. His maintenance style is "whatever comes, deal with it" and for decades, he maintained the house very cheaply by his own ingenuity - he singlehandedly replaced the aging shingle roof with metal - but as age catches up with him, it becomes harder and more expensive as he has to pay workers to do things he once did for himself. Entropy does not only act on things, it also acts in people.