Unpredictable Futures: Bonhoeffer and Bots

With Poets Training AI It’s Worth Asking: What Makes Us Human?

Everyone was waiting for just one thing. World War II had interrupted the work, and now Dietrich Bonhoeffer found himself behind bars. It was 1943. The German theologian started his magnum opus, Ethics, in 1940. Busy assisting Jews and shirking as much official work as possible, however, Bonhoeffer didn’t have much time to write.

But here in Tegel Prison things changed. For a year and half he lived, as Devin Maddox and Taylor Worley say in a wonderful article for Christianity Today, “in relative comfort, allowing him the time and space to read and write prolifically for most of his imprisonment.”

So, he jumped back into Ethics, right, the partially completed, urgently needed book everyone anxiously awaited?

No.

As Maddox and Worley detail, along with piles of letters, Bonhoeffer wrote poetry, worked on a play, and started a novel. Given his passive and active resistance against the Nazi juggernaut, including joining an unsuccessful plot to assassinate Hitler, this might strike us as curious, maybe even disappointing.

“Bonhoeffer spent his final months,” they say, “creating art.”

Wasted Effort?

The reason some might judge this pursuit frivolous, they say, owes to our tendency to reduce people to what we deem their primary purpose. If you’re an activist theologian working against a maniacal and murderous regime, we expect you to keep up the routine—not drop out and start telling stories, let alone counting iambs.

Activist theologians are on the clock, after all. And as soon as the authorities could nail Bonhoeffer for his involvement in the assassination plot, time ran out. His enforced writer’s retreat was cut short, and he was shunted off to more forbidding confines, including Buchenwald and eventually Flossenbürg.

The Nazis hanged him there just before the end of the war in April 1945. And that book everyone was waiting for? He never finished it. Nor, it’s worth saying, did he finish the novel. So, was it all a waste? We did get some penetrating poetry. Here’s a bit from one of those prison poems, “Success and Failure”:

Success is full of foreboding,

failure has its sweetness.

Without distinction they appear to come,

the one or the other,

from the unknown.

Both are proud and terrible.People come from far and wide,

walk by and look,

pausing to stare,

half envious, half afraid,

at the outrage,

where the supernatural,

blessing and cursing at the same time,

entangling and disentangling,

sets forth the drama of human life.

What is success and what is failure?Time alone distinguishes.

An apt thought for a man in prison for virtues misconstrued by an unjust state as crimes. But it’s the motivation behind the lines that matters most of all. Why write poetry when more productive pursuits await?

“What appears to us as such a curious choice must have been a desperate attempt to hang on to his own humanity,” write Maddox and Worley. “In the midst of threatening death, creativity allowed him some recovery of his most authentic self. . . . Creative expression is our life-giving cry of freedom.”

The Consolation of Art

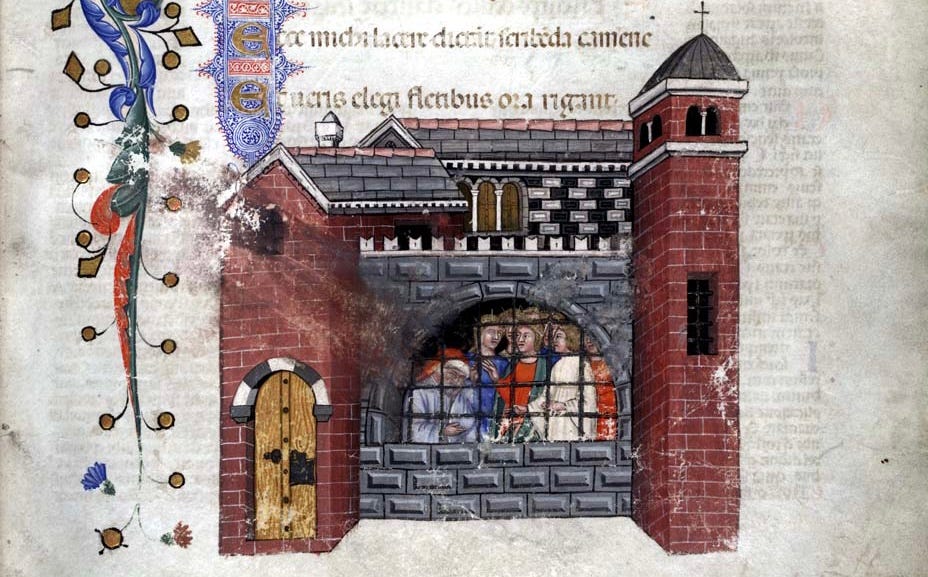

I’m reminded of another writer and (occasional) theologian imprisoned for supposed involvement in a coup. Boethius was partway through translating Aristotle’s corpus when he was accused of trying to undermine the sixth-century Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great.

Behind bars and awaiting his own execution, did Boethius resume his translation efforts? It might have changed the course of Western history if he had.

As it stands, it took the Arabic translation movement and half a millennium of additional time for the Latin West to access the Greek philosopher because Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy instead. As with Bonhoeffer, art trumped productivity. Scholasticism could wait.

Maddox and Worley provide a theological rationale for this tradeoff. As humans, we bear the image of a God who creates. Creative engagement allows us deep and needful access to what makes us human; in creating art we are returning to form.

But one needn’t hold Christian convictions to recognize art as fundamentally generative and affirming of our humanity. And what makes us human is perhaps more relevant now than ever.

Do Robots Write Poetry?

I’m unsure if we ever satisfactorily answered whether androids dream of electric sheep, but let’s complicate it with another puzzler: Do robots write poetry? As it happens, Bonhoeffer’s prison pastime intersects with a fascinating story out of Silicon Valley.

“A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as Scale AI and Appen, are recruiting poets, novelists, playwrights, or writers with a PhD or master’s degree,” reports Andrew Deck for Rest of World. “Dozens more seek general annotators with humanities degrees, or years of work experience in literary fields. . . .”

The reason? “The companies say contractors will write short stories on a given topic to feed them into AI models,” explains Deck. “They will also use these workers to provide feedback on the literary quality of their current AI-generated text.”

Poets training robots: It’s a sci-fi story come true. It also exposes something interesting about the basic divide between human creativity and its algorithmic derivatives. “Tools like ChatGPT were built to mimic human writing,” says Deck, “not to innovate on it.”

When we ask ChatGPT to write us a poem or tell us a story, it’s doing so based on all the data upon which it’s been trained, including innumerable books of poetry and other works of literature. One dataset used by Meta, Bloomberg, and others contains over 191,000 books, including novels—much to the frustration of many of their authors.

And that frustration is illuminating, maybe even essential. Where, after all, does poetry come from? Thinking of Bonhoeffer and Boethius, from a place of longing and suffering, of fraying hope and discouragement and the need for self-assertion amid humiliation and abasement.

We can train AI models to mimic the product of those emotions, but I don’t see how even the most advanced models can originate such products without experiencing a feeling as simple as frustration—let alone the higher yearnings and struggles of the heart.

The Choice to Create

I’m a fan of AI, as I’ve made clear here before. I see tremendous upside from its ongoing development as a creative partner in all sorts of human endeavors, including writing and translation, but also medicine, manufacturing, finance, energy, engineering, and more.

The whole point of technology is to emancipate human labor by enhancing human capabilities. As our tools allow us to transcend our native limitations, we are free to pursue other, higher aims—such as, for instance, art.

Critics of AI say that as technological capabilities expand we risk dehumanization. And maybe we do, though I admit I find these arguments unconvincing for now. While the future of AI is every bit as undetermined and unknowable as all other futures, there still stretches a vast gulf between man and the machine.

The examples of Bonhoeffer and Boethius teach us this as well. Knowing all the reasons for doing one thing—say, completing Ethics or translating Aristotle—we can nonetheless blow it off and write a play, or paint, garden, make music, bake bread, dance, and more. The choice to create is every bit as human as the ability to do so.

Wasted effort? “Time alone distinguishes.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Before you go, see these:

In all of this discussion of AI and its impact, there is a certain myopia, as if the technologically driven modern world has all the data on life on earth to be able to feed into AI. I was reminded of how little we actually know this week when I posted an article on learning the Wolof language, an oral tribal language that only within the last few decades has begun to have a standardized alphabet and a few grammar manuals created. As an experiment, I found an internet AI translator that claimed in could translate Wolof and entered a well known Wolof proverb. The translation generated wasn't remotely close to the actual meaning, because too little internet data on Wolof exists. There are hundreds of such languages spoken by people in mainly oral cultures with little to no access to the internet. And language is only one of many areas of human knowledge where we lack all the data, and it will take human effort and ingenuity to find all that missing data. Since we have only got as far as we have in several thousand years of recorded human history, this present civilization will probably decay as all previous civilizations have long before AI has all the data.

Furthermore, the thing about the useful applications for AI is that those applications require human knowledge to restrict the amount of information AI recieves, or the results will be inaccurate. As the reports that triggered the stock market crash in July showed, AI gets stupid when fed irrelevant data and learning from itself further confuses it. An AI medical imaging application for humans would become inaccurate by feeding it information on the anatomy of non-human mammals and reptiles. It would serve no purpose to feed the AI used decode the Herculaneum scrolls information about languages other than those in which the scrolls are written. An AI poetry generator that is fed everything from beatnik poetry to Petrarchan sonnets has to be told which type of poetry is wanted.

But there is no limit to the ways in which humans can use information. Our five senses and knowledge of what it means to be human mean that we can learn quickly to lay aside and rule out irrelevant data for any given task, but that we can also recombine apparently unrelated data in creative ways to create something new. An AI fed only poetry written before 1944 won't create beatnik poetry, but humans did.

As an author, this makes me uncomfortable. “… writers with a PhD or master’s degree,” Great, MFA writers helping to program AI writing machines. Hasn’t Big Publishing already been taken over by young, inexperienced, entitled ‘new-think’ writers as it is.

But I suppose as everyone says, ‘change is good.’ Our betters in the scientific and political realm have already inflicted National Socialism and Communism on humanity. Next it will be AI-driven paradise where everyone will sit around and eat rainbow stew and God knows what will happen.

But, on the other hand… AI is the sorcerer’s stone and if China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea have it, so must we. I can already hear, “If we don’t put more money/effort/etc. into AI, China’s AI will kick our AI’s ass.

“I see tremendous upside from [AI’s] ongoing development as a creative partner in all sorts of human endeavors,”

Yeah. Me too. But ‘partner’ implies equality. Will it stay a partnership? I doubt it. I’m inclined to say, “it’s human nature that one party will, in time, consider itself a more worthy partner than the other. But we’re not speculating about ‘human nature.’ Or… are we? Aren’t we designing that into the machine somehow? Human nature and all its flaws?

“As our tools allow us to transcend our native limitations, we are free to pursue other, higher aims—such as, for instance, art.”

Hmmm. I find myself recalling how mental hospitals in the 20th century provided ‘arts & crafts’ to fill up the patients’ time, and prisons had ‘shop’ where the prisoners could work at something so they wouldn’t go ‘crazy.’ And weren't both of these institutions places where humans were prevented from leaving?

Did I ever tell you I was paranoid? Well, I am.

Joel, this is fascinating. Thanks for sharing it!.