AI Job No. 1: Save the Humans

Bookish Diversions: Chaucer’s Vacation, Elizabeth’s Secrets, AI Translators, Ancient Book Slaves, More

¶ Vacationing with Chaucer. Everyone needs a break, and that’s always been true. But it was still a surprise to realize the only text written in the hand of Geoffrey Chaucer, father of English literature, was a hastily composed vacation request.

Writing is usually bivocational, a nice way of saying it doesn’t cover the rent and authors often require a second stream of income. In Chaucer’s case, he worked a dozen years as controller of the London Wool Quay, a tax enforcement role ensuring the king got his cut of the wool business moving up and down the Thames.

It was tough work, and the author of The Canterbury Tales needed a breather. So, how did the king’s functionary get PTO in the fourteenth century? Chaucer scribbled out a formal request.

“Chaucer may well have known in advance that his request for leave of absence would be granted,” said Richard Green, professor emeritus of the Ohio State University, “but he was still obliged to go through a formal process that required him to draft his petition in writing, get the chamberlain to confirm that the king had approved it, and then have it sent over to Chancery to receive official authorization.”

This missive didn’t rise to the level of literature. Instead, it’s the medieval equivalent of a slapdash email request: a small piece of parchment scrawled with two wavy lines of text, “short, simply worded, and carelessly written . . . both informal in tone and casual in execution.”

Importantly, however, Green argues Chaucer penned the note himself, making this otherwise insignificant time-off request his only surviving handwriting.

¶ Virgin Queen’s secrets come to light. For the last 400 years, anyone more than casually curious about the reign of Queen Elizabeth I has turned to the authoritative account by William Camden, written during her lifetime and finished after her death:

Annales: The True and Royall History of the Famous Empresse Elizabeth, Queene of England France and Ireland &c.: True Faith’s Defendresse of Diuine Renowne and Happy Memory: Wherein All Such Memorable Things as Happened During Hir Blessed Raigne, with Such Acts and Treaties as Past Betwixt Hir Ma[ies]tie and Scotland, France, Spaine, Italy, Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Russia, and the Netherlands, are Exactly Described.

Camden’s Annals for short.

Now researchers, using new imaging technology that transmits light through the original manuscript pages, are upending prior conclusions about Camden’s subject. In hundreds of instances, Camden redacted and edited his work to appear more neutral and appease his later patron, Elizabeth’s successor, King James.

Pages of Camden’s manuscript, reported the Guardian, “had been either over-written or concealed beneath pieces of paper stuck down so tightly that attempting to lift them would have ripped the pages and destroyed evidence.” The new technology allows researchers to see beneath these overlays and read the original text.

“Camden’s Annals were deliberately rewritten to present a version of Elizabeth’s reign that was more favorable to her successor,” said British Library’s Julian Harrison. He called the new insights “heart-stopping.” Revelations, summarized by Fine Books and Collections, include Camden’s dueling takes on:

Elizabeth’s rival, Philip II.

Camden’s original claimed Philip “had no imperial skills” and died riddled with parasites, deemed divine punishment.

Revised to remove those details and soften the judgment.

Rome’s excommunication of Elizabeth I.

Camden’s original claimed pope excommunicated the queen because of “spiritual warfare.”

Revised to soften inflammatory language about the episode.

Elizabeth I’s naming of her successor, King James.

Camden’s original contained no mention.

Revised to include Elizabeth naming James on her deathbed, ensuring his legitimacy.

King James’s supposed plot to assassinate Elizabeth.

Camden’s original included the wild claim.

Revised to soften the charge, saying instead that James had been “accused . . . with ill affection towards the Queen.”

Camden’s manuscript consists of ten volumes with hundreds of these sorts of revisions. “What’s going to be interesting,” said Harrison, “is how modern interpretations of Elizabeth I, such an important historical figure, are potentially going to be changed.”

¶ Tools to transcend our limitations. Both of these diverting stories have merit in their own right, and I knew I wanted to share them here the moment I read them. Then I got to thinking about an underlying theme. What unifies the stories of Chaucer’s time-off request and Camden’s portrait of Elizabeth? Both converge at the intersection of human labor and technology.

Humans are limited, hence Chaucer’s need to unplug. And tools allow us to overcome our limitations, e.g., new tools that permit us to illumine (in this case literally) our understanding of history. The very human work of making meaning and adding value in the world is limited by the scope of the work we can undertake and thus depends on the technologies we’ve developed—and continue to develop—to transcend our limitations.

The lever, the wheel, the plow, the printing press all present examples. So does AI.

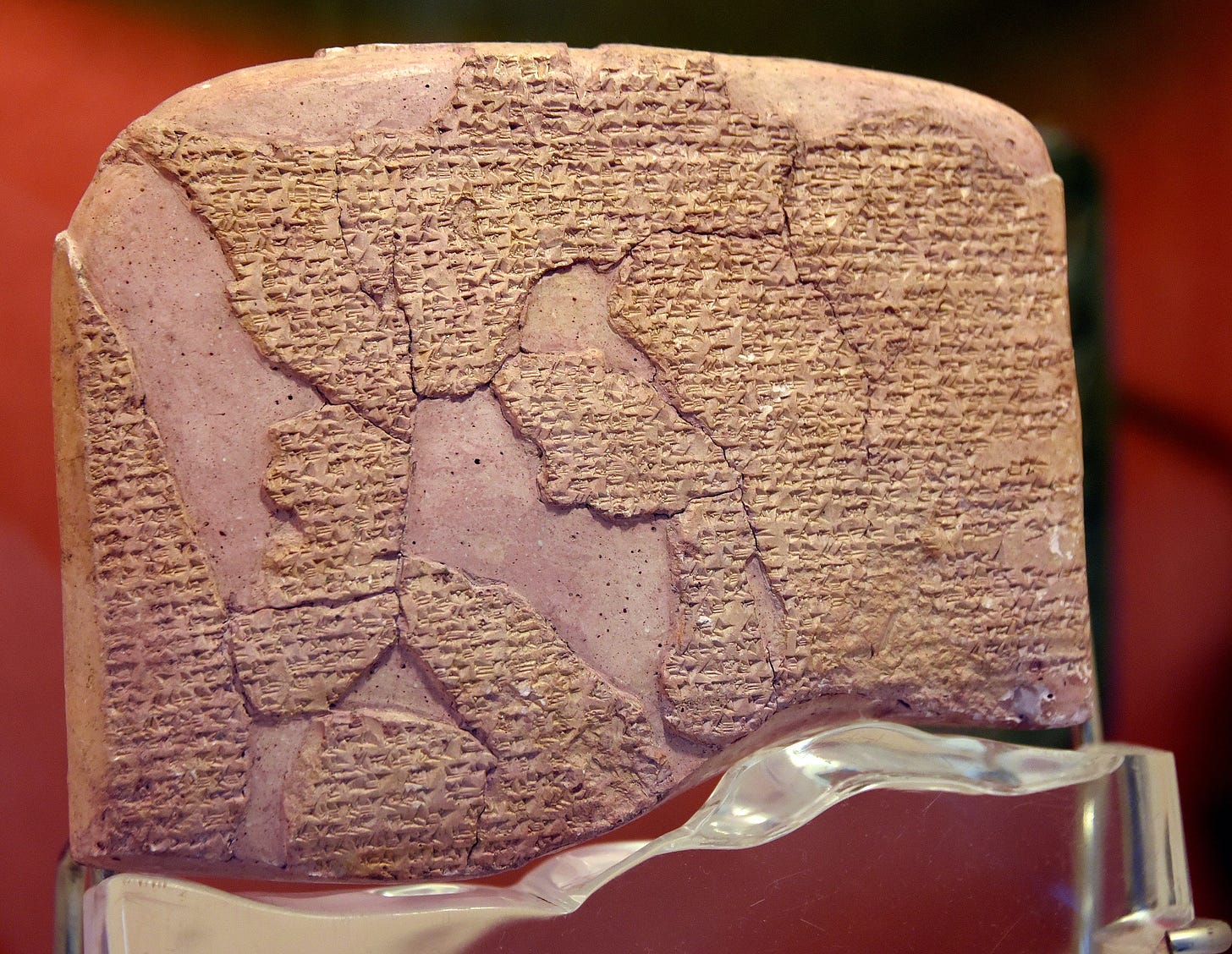

I can appreciate people’s unease about generative artificial intelligence but don’t share their worries. I’m more bullish on the potential gains. Consider the researchers who developed a neural machine translation model for translating ancient Akkadian. Says Kevin Dickinson, writing at Big Think,

Hundreds of thousands, by some accounts more than a million, Akkadian texts have been discovered and today lie in museums and universities. . . . Each one has the potential to teach us about the life, politics, and beliefs of the first civilizations, yet this knowledge remains locked behind the time and manpower necessary to translate them.

There are only so many humans who can translate Akkadian. And like Chaucer they can’t work 24/7. Those limitations hem in our potential knowledge of the ancient world. But what if you could allow AI to do the grunt work?

The model translates texts almost instantaneously and with remarkable flexibility, accounting for nuances such as genre, symbol variability, and more. It’s not flawless, far from it; the model occasionally mistranslates words and has the same so-called hallucination problems other AI models have demonstrated. But it represents a remarkable breakthrough nonetheless.

“All told,” says Dickinson,

the AI model works best when it is translating short- to medium-length sentences. It also does better with more formulaic genres, like royal decrees and administrative records, than literary genres such as myths, hymns, and prophecies. With more training on a larger dataset, the researchers . . . aim to improve its accuracy. In time, they hope their AI model can act as a virtual assistant to human scholars. The AI can provide the raw translation quickly, while the scholar can refine it with their knowledge of historic languages, cultures, and people.

That’s worth repeating: “They hope their AI model can act as a virtual assistant to human scholars.”

¶ Doing more, doing differently. Tools don’t replace humans; they (a) enable them to do more or (b) enable them to do differently. In the case of both Camden’s Annals and the Akkadian tablets, tools allow humans to do more—permitting them to see what was previously invisible or process what was previously too vast.

The “virtual assistant” language fits perfectly and tracks with where and how AI is being deployed in the workplace. As Alexandra Samuel recently noted, conversations about hybrid work now assume AI collaboration. The data-processing horsepower of AI enables workers in all sorts of industries to transcend their prior limitations, just like the Akkadian translators. And AI offers huge gains in ideation and other areas as well.

That covers doing more, but what about doing differently?

Tools don’t replace humans, but they do liberate them to pursue other endeavors and find new purposes for their unique capabilities. Human curiosity, ingenuity, resourcefulness, persistence, and optimism are too valuable to expend on activities mere machines can manage.

Technological development has always assumed as much. Hence the aforementioned lever, wheel, plow, and—yes—printing press.

¶ Upgrading the infrastructure. Recently writing about Roman slavery at Current, Nadya Williams mentioned the comedies of second-century BCE comic Plautus and Stephen Sondheim’s 1966 musical and movie, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, which trades on tropes borrowed from Plautus. “There are jokes aplenty,” writes Williams.

And yet, if we pay close attention, we may notice a startling element that is taken for granted in the Roman context. This something is present in every scene and is even more readily visible in the film version than we might notice if we were just reading Plautus’s originals today: enslaved people are everywhere, just as they were everywhere in the Roman world in Plautus’s time. And their lives, as the comedies readily and unapologetically show, were bleak.

The Romans were continuously at war during the third century BCE, a period of rapid and dramatic expansion. With each conquest, there were more people to capture and sell into slavery. Once enslaved, they became absorbed into the urban and rural landscape. Some could be freed eventually, but definitely not most.

Not a lot of vacations with this arrangement.

Slaves were plenteous in the ancient world, as much as a third of the population in Italy. The mass exploitation of unfree labor allowed the Romans significant economic advantages. Drudgery could be offloaded onto the enslaved, along with demeaning or tedious work of any kind, including reading, writing, and copying manuscripts, the only way to reproduce texts before the printing press.

Pliny the Elder kept slaves to read to him when he was bathing, being carted around the city, or reclining outdoors on summer afternoons. And while a writer such as Cicero might copy his own manuscripts, he was an outlier. What’s more, the ancients denigrated manual labor. Most who could read and write placed no value in the acts of reading or writing—any more than they did herding pigs. As a result, literary engagement and manuscript production relied on slaves or freedmen (those once enslaved but later manumitted). And as the grousing of medieval scribes in colophons and marginalia attests, copying manuscripts was a grueling chore—hard on the eyes, the hand, the back, and more.

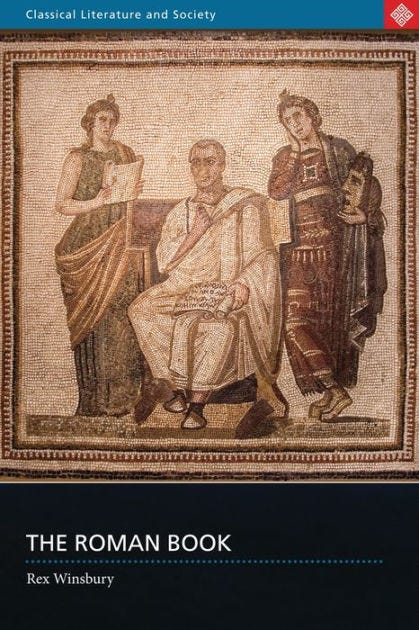

The use of slaves was so ubiquitous writer Rex Winsbury referred to them as the “infrastructure” of the Roman book trade, and the work of writing was so challenging that when Christian monastics replaced slaves as the primary copyists in the medieval period, they did so as a form of ascesis—rigorous self-denial for spiritual ends.

There were tradeoffs to this reliance of unfree labor. When the cost of brutal work can be absorbed by people other than the beneficiaries, those beneficiaries have no incentive to reduce the costs. Technological development progressed slowly in the ancient world because exploitative labor was too cheap and easy to come by.

This began to change in the medieval period, as sociologist Rodney Stark and historian Lynn White have argued. Monastic communities, desiring to free up more time for prayer and study, adopted the use of labor-saving technologies, even pioneering their development and use. The simple rubric? If an animal or tool can free a human for higher and better use, the animal or tool should be adopted. Human capabilities are too precious to waste on any activity that nonhumans could accomplish, even if only in part.

Generally speaking, a culture eager for technological development resulted from this shift. And when it came to reproducing of texts, Europeans were ready and rapid adopters of the printing press, spurring an intellectual revolution in the West. Manually copying texts imposed severe limits on the number of books that could be produced; same with reliance on parchment as the primary writing surface. Paper and the printing press changed all of that and the production of books ballooned in the fifteenth century and beyond.

To stress the scope of this change, examine the adjoining chart. In 900 years of manuscript production, from the sixth to the fifteenth centuries, European scribes produced about 10.9 million books in all. But in just 150 years of print, between 1452 and 1600 printers produced some 212 million books—a 1,846 percent increase in a fraction of the time. And, on net, humans gained these benefits while being spared more grueling work machines could do.

¶ Save the humans. Chaucer deserved time off because human’s possess their own labor (as an inalienable right of each person) and shouldn’t be worked into the ground. The same inherent human dignity that justifies and necessitates rest from our labors encourages labor-saving devices and tools—including AI.

As we enhance our capabilities through our tools, we emancipate more of what makes us human. Yes, there’s much to learn and negotiate along the way, but the spread of virtual AI assistants can save human talents and gifts for what only humans can do, allowing us to do more and do differently than we have until now.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post: