Our Libraries Tell Us Stories, if We Listen

Bibliophile Stuart Kells Discusses His Personal Collection, Publishing History, What Guides His Writing, More

My first exposure to Australian author and bibliophile Stuart Kells came through his book The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders. I saw it mentioned on Twitter in 2017 and ordered it directly from his Australian publisher, Text Publishing in Melbourne, because I didn’t want to wait for the 2018 U.S. edition published by Counterpoint.

My impatience was rewarded. It’s a delightful read and soon began racking up recognition and plaudits, including being shortlisted for the Australian Prime Minister’s literary award and the New South Wales Premier’s general history prize.

I followed that experience as soon as possible with Shakespeare’s Library, Kells’s fascinating look at scholars and crackpots intent on finding the personal library of the world’s most famous author.

Along with these titles, Kells has written more than a dozen books, several of which have been published internationally. His history of Penguin Books, Penguin and the Lane Brothers, won the Ashurst Business Literature Prize in 2015, and Kells won the Ashurst prize again in 2018 for The Big Four with his coauthor, Ian Gow.

Kells’s shorter works have also been published in Smithsonian, The Paris Review, The Guardian, Daily Beast, Lapham’s Quarterly and LitHub. He’s adjunct professor at La Trobe University’s College of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce. I wanted to talk with him about his own library, publishing history, and what guides his personal writing.

Miller: You have a lovely—and large—personal library. What was the impetus for your book collecting? And what motivates you today?

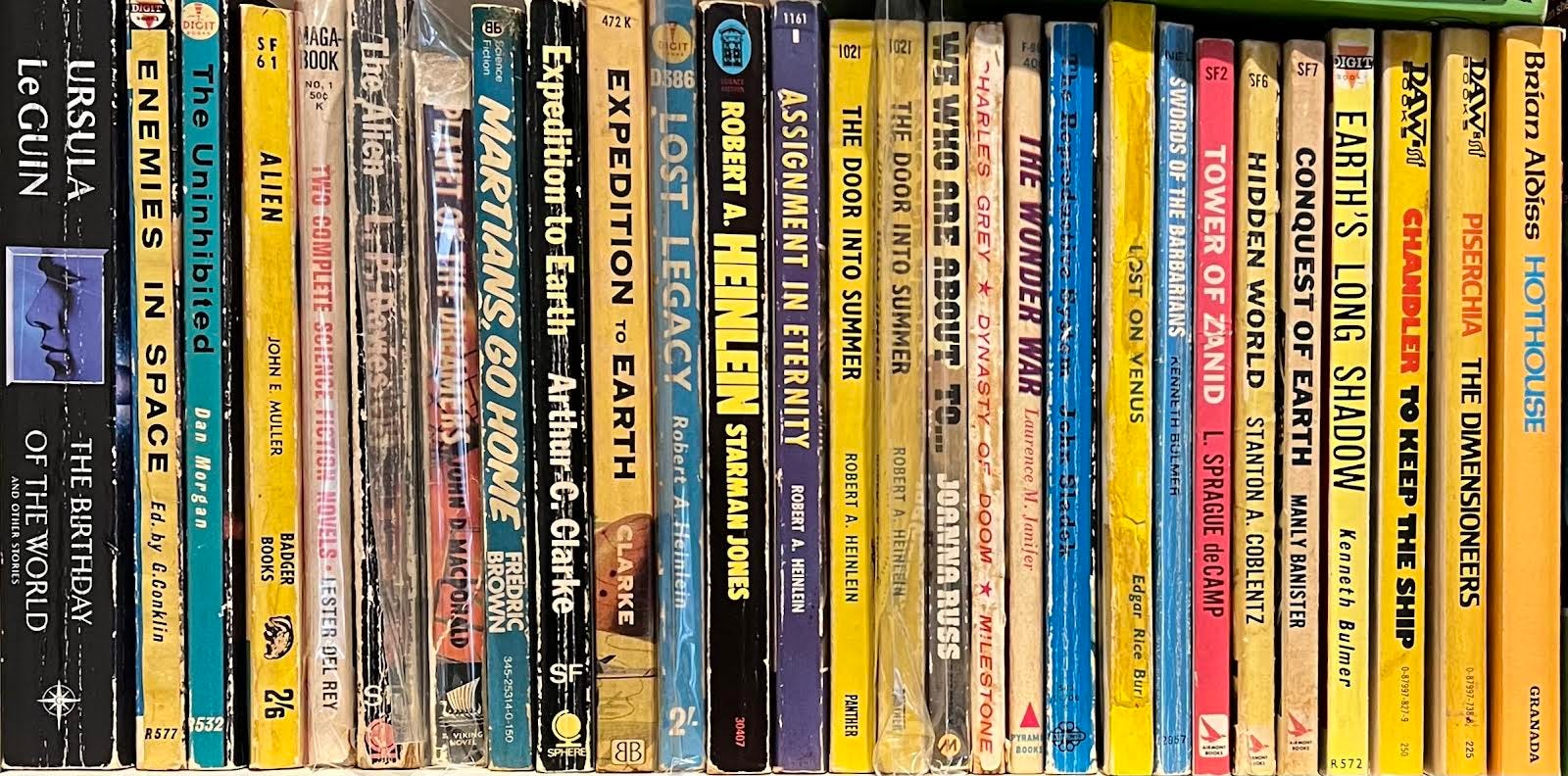

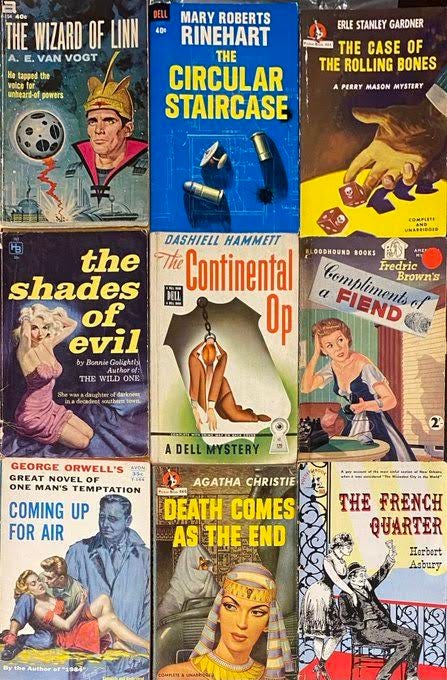

Kells: Thank you, Joel. My library is a large part of my life. I started collecting when I was in high school—mainly old and inexpensive paperbacks because that was all I could afford at that time. Midcentury paperbacks with vibrant covers and pulpy contents were portals to a different world.

Later on, I started “running” books, which means finding underpriced books and selling them to bookshops. It was enjoyable and sometimes exciting work. Every book I bought and sold was a mental puzzle and a game with a financial prize. Very satisfying to find underpriced books even at the fussiest, stuffiest “antiquarian” bookshops; no bookseller can be an expert in every area.

Today, my library is very much a working resource and an engine for my writing. It’s also a storehouse of physical media in a digital era. In the battle between physical books and ebooks, I’m very much on the side of paper and ink.

How many books are in your collection and what genres are represented? Are there any that are your favorites?

I’m not sure precisely how many books. There were times in the past when I had more books; they were stacked against living-room walls and they filled spaces under tables and beds and sofas. The size of my library expands and contracts over time, like the breathing of a sleeping monster.

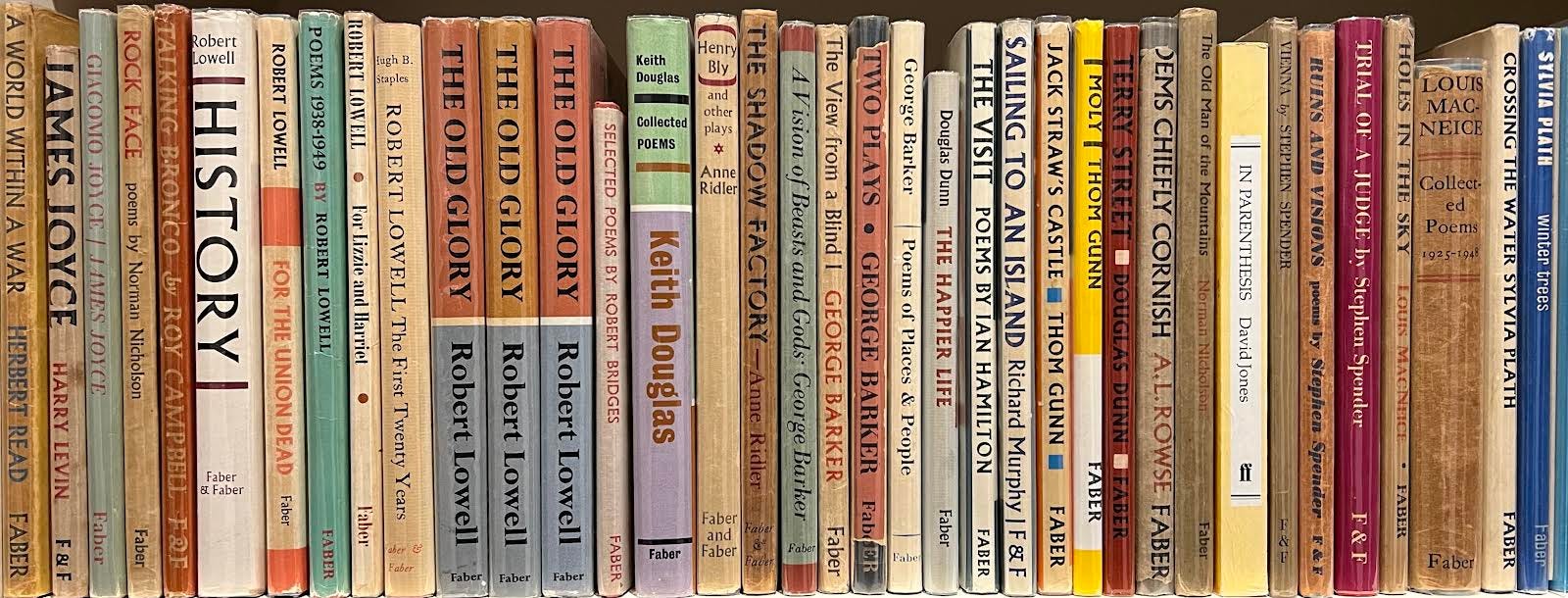

Right now I have substantial collections of “books about books,” literature, pulp fiction, ephemera, art, fashion, surfing, water, toys, Penguin books, Bloomsbury, Shakespeareana, Wiseana, Victoriana, the middle ages, modern history, Australian history, economics, and books in several other categories.

I also have smaller collections of philosophy, theology, pedagogy, psychology, institutional histories, militaria, true crime, private press books and eighteenth-century books. Plus some comics and manga. The library’s guiding principles include attraction, condition, usefulness, and serendipity.

I have a lot of favorite books. There are whole categories of books that I can’t resist when I see them for sale (for a reasonable price), such as Edward Ardizzone octavos, Faber poetry editions, Hogarth Press books, morocco bindings, and midcentury pulps from publishers such as Ace, Dell, Pocket Books and Popular Library. These come to mind immediately, but the list of favorites is long.

“The size of my library expands and contracts over time, like the breathing of a sleeping monster.”

—Stuart Kells

What is the rarest book in your collection?

As you know, there are many different sides to rarity when it comes to books. Some volumes are rare because only a small number were originally produced. My collection of Thomas Wise books is an example. Some of those were produced in print-runs as small as thirty copies (while noting that the limitation statements of the Wise books are notoriously unreliable!). My copy of John Fry’s Pieces of Ancient Poetry is another example: it is one of only six “specials” that were printed in 1814 on blue paper.

Alternatively, some volumes are rare because they have unique provenance. Two examples from my collection: a scarce book from the library of Australian colonial judge Redmond Barry (Catalogue of the Royal and Noble Authors of England, Dublin, 1759); and Kornmann’s books on love, marriage, and virginity (the 1629 edition, from the library of erotica historian G. Legman).

Some books are rare because of their condition. In 2023, sci-fi and adventure books from the 1940s and ’50s in good condition are rare survivors. The same is true of magazines such as Amazing Stories, Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories; and modern first editions that still have their dust jackets in a good state of preservation. I have examples of all of these rarities, along with others, such as “press books” that were printed in small runs using traditional methods.

Given the range of books in your library and the timeframe represented, could a story about the changes in the publishing industry emerge just by looking at them? If so, what would it be?

The books definitely tell a story. They represent different trends and fashions in publishing and book collecting. Certain types of books exemplify their era: examples include modern firsts from the twentieth century; private press books; Victorian decorative cloth bindings; midcentury “school stories” and annuals; mass-market pulps; and scholarly eighteenth-century books printed on robust paper made from cloth rags.

What are some of the things that the story tells us? The best books achieve a harmony between form and content. Older books are often more robust and well made than new books. Physical books offer aesthetic and cultural experiences that ebooks do not. Grouping similar and different books together in a library tells a story that is bigger than the sum of the parts. Private libraries are connected over the centuries in complex, fractal ways.

“Grouping similar and different books together in a library tells a story that is bigger than the sum of the parts. Private libraries are connected over the centuries in complex, fractal ways.”

—Stuart Kells

You’ve written on the history of publishing. What is one of the most astonishing facts you uncovered in your research?

My book on the three brothers who founded Penguin Books in 1935 was built on a series of revelations. My research showed that the popular idea of Allen Lane as a publishing genius who came up with the idea for Penguin in a moment of inspiration is simply and demonstrably untrue.

He wasn’t a very bookish person at all, and his success arose in part from personal ruthlessness and in part because people around him were forever clearing up his mistakes! He was a master myth maker—in a self-serving way. Subsequent generations have bought into the myths he wrought.

I’m thinking about all of your pulp novels and the opprobrium they’ve endured as a genre. It may surprise some, but that was true for all fiction at one point or another. Cervantes jokes about it in Don Quixote, and nineteenth-century lending libraries were ambivalent about novels, even against them. How do you respond to denouncing whole classes of books? What’s driving that?

You are right in saying there have always been prejudices against different types of books and different modes and forms of writing, and in hindsight the prejudices nearly always look ridiculous. I’ve written previously about how, early in the seventeenth century, the leader of the Bodleian Library in Oxford argued strongly that the library should not collect playscripts—such as the works of Shakespeare—because they were “baggage books” unworthy of collection.

One of the biggest trends and paradoxes in rare book libraries over the past century: books from the fringes of society and respectability—such as pulps, erotica, and radical, counterculture literature—are now hotly sought-after, and they complement very well the more traditional focuses of rare book libraries and librarians.

What is driving this? The concepts of art and literature are fundamentally fuzzy and unstable, and judgments about literary and cultural worth are always provisional. Also, decisions about what to preserve are nearly always political; they reflect social structures of power and, sometimes, oppression. Those structures are contingent and contested, as is the concept of a meritorious book.

You are the editor of Library Planet. What is it, and what do you enjoy most about the work there?

Library Planet is a crowd-sourced travel guide to libraries around the world. It was founded in 2018 by two Danish librarians, Christian Lauersen and Marie Engberg Eiriksson. In October last year I took over as editor, which is a delight and a privilege. I love reading and writing about libraries, and connecting with book people around the world.

As editor, I’ve continued Library Planet in the mode established by Christian and Marie, while also adding more libraries from the new world, as well as topical bibliographical pieces, such as a recent interview with Voynich manuscript expert Lisa Fagin Davis. I also plan to add profiles of private libraries to the Library Planet site.

What is your favorite part about a writing project?

I love delving into new fields and discovering new things, while making use of everything I’ve learnt and experienced. I’ve had a diverse career, and every part of my career has been useful in my writing. My approach to writing is somewhat geometrical: I like finding similar patterns and shapes in diverse fields and then pointing out the connections, and following where they lead. The biggest “sweet spot” for my writing is the intersection between the arts and commerce. That intersection is not very crowded, and it allows me to look at familiar things in new ways.

Early in my writing career, another author gave me some good advice: go after big topics. I’ve done that, for the most part, and I’ve also sought out big topics that are best written about from Australia. Examples include the Argyle diamond mine, the “Alice” financial market invention, aspects of Shakespearean heresy and Bardolatry, and (unexpectedly) the history of Penguin Books (because two members of the Penguin-founding generation of the Lane family ended up living in Australia).

I relish the challenge of finding suitable topics and turning them into books that work as pieces of writing, scholarship, and publishing.

“The concepts of art and literature are fundamentally fuzzy and unstable, and judgments about literary and cultural worth are always provisional. Also, decisions about what to preserve are nearly always political. . . .”

—Stuart Kells

Least favorite?

There are few worse feelings than when a book comes back from the printer with a typo or some other kind of glitch or error. I’ve been fortunate with my most recent books, but a lot can go wrong in publishing, and I’m always at least half terrified of typos.

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Language is not an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

Very difficult question. Having worked a little bit in publishing, and having been on the writers’ festival circuit for more than two decades, I’ve met many living authors. But if death—like language—is not an obstacle, I’d stretch the fantasy and invite some of my deceased heroes: perhaps Shakespeare, John Donne, Virginia Woolf, or Kate Jennings. Or maybe William Burroughs, Philip K. Dick, and Frederic Manning. Or Inga Clendinnen, W.G. Sebald, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. I could do this all day!

How would the conversation go? I’d report back to the authors on their impact and importance in the human project; how they’ve given us the words and tools to comprehend and communicate otherwise incomprehensible and inexpressible aspects of human experience. And I would thank them, with a toast, for their cultural and bibliographical legacies.

That might sound a bit obvious or pedestrian, but I think ultimately most authors care about their legacies in language and humanism. My library is an acknowledgment of that. It is an instrument of respect to the authors—and their editors and publishers—who marked out the tracks that many of us now walk.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Great post - thanks - reading A History of Reading - A. Manguel- imagining an boy from Argentina, living in Berlin and reading A Tree Grows in Brooklyn in translation. The mind, it boggles!!! Love the stories!

Loved the photos in this post! I would likely have "crooked neck syndrome" if I ever got to visit Kells incredible library, walking slowly head tilted sideways to read all the titles (happens to me often in used bookstores...).