A Working Writer in a Working Library

Historian Steven F. Hayward Unpacks His Library and Gives Us a Tour

In his famed essay “Unpacking My Library,” critic Walter Benjamin mentions the chaos that prevails once the boxes are open, before “the mild boredom of order” sets in. Anyone who’s set up an old library in a new space understands the point: The rediscoveries, the possibilities—it’s all electric and exciting.

So what excitement does Benjamin want to share with his readers? Not what I hoped for, alas. “Would it not be presumptuous of me if, in order to appear convincingly objective and down-to-earth, I enumerated for you the main sections or prize pieces of a library, if I presented you with their history or even their usefulness to a writer?”

Gah, not at all! To get a sense of how a working writer uses a working library: That would be great, actually.

Thankfully, Steven F. Hayward took a professorship at Pepperdine and moved to a beautiful new home overlooking the Pacific, where he recently unpacked his own library. Here was my chance! I asked him if he wouldn’t mind answering a few questions Walter Benjamin would surely dislike. The result? A delightful picture of a writer among his books.

Hayward is the Edward L. Gaylord Visiting Professor of Public Policy at Pepperdine, before which he served as a resident scholar at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies and as a fellow of Berkeley’s Law and Policy Program. He’s also a senior fellow at the Pacific Research Institute in San Francisco, which is, incidentally, where I first met him.

He’s written on public policy and economics for the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago Tribune, National Review, Reason, and dozens of other outlets. He’s also the author of several books, including the two-volume history The Age of Reagan; Greatness: Reagan, Churchill, and the Making of Extraordinary Leaders; and Churchill on Leadership, the first book of Hayward’s I ever read—way back in college.

What surprised you most about the process of unpacking your library?

One problem is that I realized I had more than one copy of a book. Another impression was “Why did I ever buy [or read] this book,” as it may have become obsolete or less relevant. (Not true for classic titles of course.) So it is teaching me to be somewhat more discriminating in what I think I will want to read, because of course like most book buyers, I have acquired more books than I’m likely to get through.

“Like most book buyers, I have acquired more books than I’m likely to get through.”

—Steven F. Hayward

What’s the size of your collection? How has it contracted or expanded over the years?

No idea. I tried counting up my books about thirty years ago, when I went over 1,000, and I’d guess I have maybe 2,500 or more by now. But I am going to shed a lot of books I used for research on books or academic projects from twenty years ago or more and am unlikely ever to need again.

How are you organizing all the books—by author, genre, chronology? What’s the scheme you’re trying to follow? Have any books frustrated the effort?

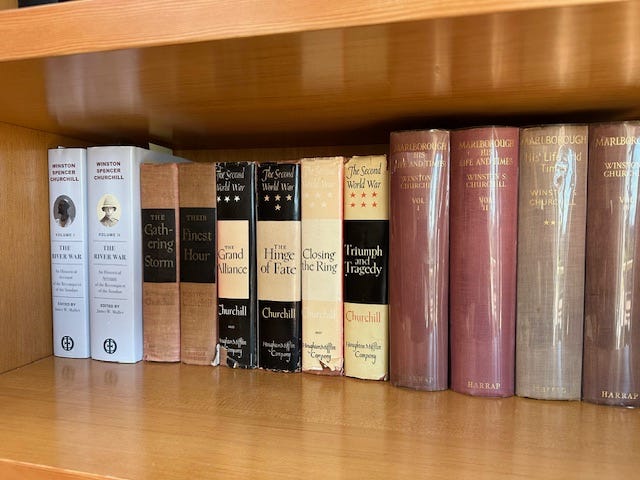

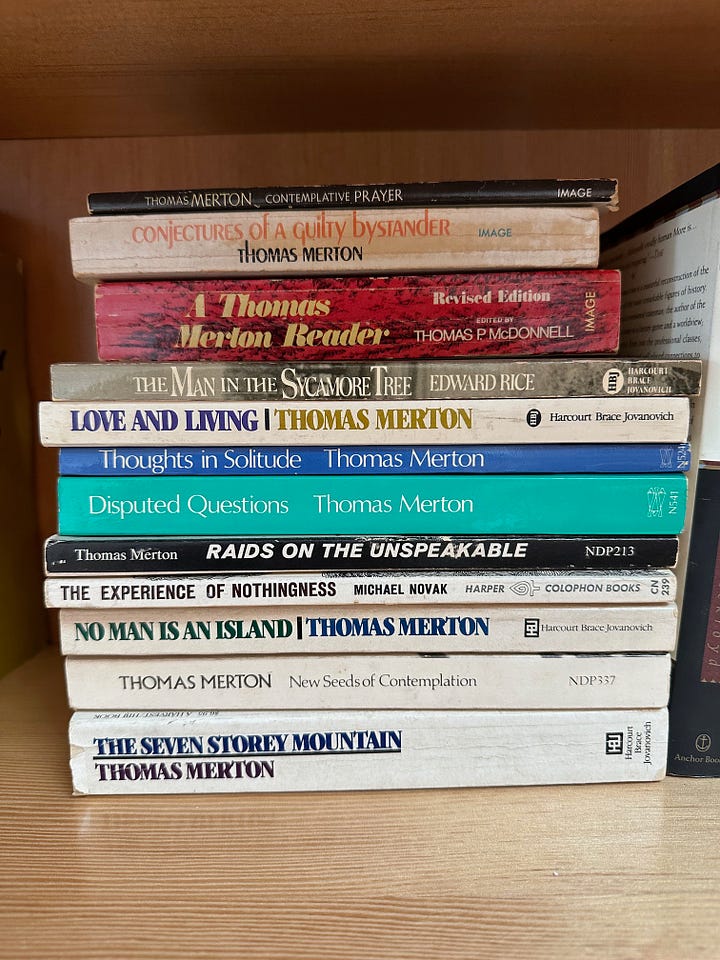

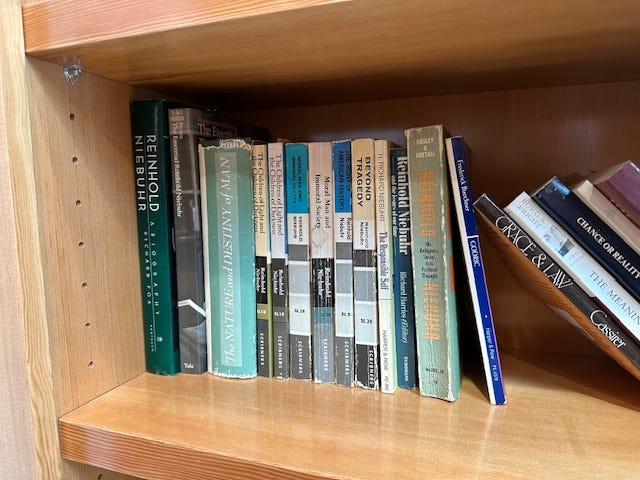

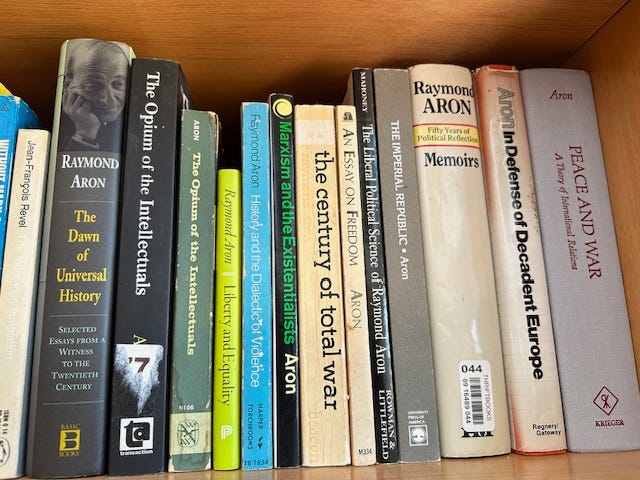

I have a totally idiosyncratic scheme, with large areas by general theme. One wall is mostly European history and politics, the opposite wall American history and politics; a third shelf is literature and criticism. I have a small upstairs study that is theology and philosophy. My academic political science and law books are all bundled in a separate building that is my home office.

But within each general category I then go by author, though this is where it gets tricky. Just where do you put Orwell? English history and politics, or literature? I choose to group him with Lionel Trilling in literature, along with Arthur Koestler, though this is not obvious. Roger Scruton has a whole shelf to himself, because he is impossible to categorize.

I’d love to hear how you use your library, both for personal and professional purposes.

For me it is a massive reference library, either to retrieve or review something I have read before and want to cite, or to answer the question, “I wonder if so-and-so has some useful thoughts on a current issue that I haven’t ever read before.” Even though the Internet now makes this kind of referencing easier, I am old fashioned and like to see it in tactile form—in part because when you go through a book instead of an Internet result, you often have a lot of serendipitous findings.

“I am old fashioned and like to see it in tactile form, in part because when you go through a book instead of an Internet result, you often have a lot of serendipitous findings.”

—Steven F. Hayward

How does the organization of the library serve those ends?

I have to remember where certain books are! That can often be my biggest problem—remembering just where a book is. The only general solution I have is simply to look over my stacks a lot and hope I’ll have a recollection when I want to find something.

When you’re deep in a project and heavily using your library, how do you keep things straight? What helps you keep the ideas you need separate from those you don’t?

First, have lots of desk and table space. I often have a small stack of books piled up for a project or article. Next most important, is making lots of notes. I’ll often make notes or even an outline of entire books, and then assemble them in three-ring binders.

Some of these books have been in storage for a decade. What was it like unboxing books after so long a separation?

Opening up old boxes was a bit like reenacting Christmas morning. Even if I knew I had the book (I usually did), it was cheering to see it again, like an old friend.

“Opening up old boxes was a bit like reenacting Christmas morning. Even if I knew I had the book (I usually did), it was cheering to see it again, like an old friend.”

—Steven F. Hayward

I wonder about how unique titles, bookmarks, marginalia, and ephemera strike you when you encounter them. Have you been transported back to other times, places, and even mental states while sorting and organizing the library?

Oh, yes. When I was younger I tended to underline and/or make marginal notes more than I should have, and now sometimes I ask, “Why did I think that passage was of special importance?” or “I wonder what I was thinking with that marginal note?”

I developed a system I still use: I will draw a vertical line in the margin for several lines or a paragraph I think is significant, and two vertical lines for material I think more significant, and full underline for the most significant. This is a truly dumb system, however; still, I can’t seem to shake the habit.

What story does your library tell about the evolution of your own thought and interests?

One of my problems is that I’ve always been interested in just about everything (I do have a couple of science shelves, but this needs more work). Over time I think I’ve been more drawn to history than I was when younger, on the view that “history is philosophy teaching by example” (attributed to Thucydides, though no one can find it in his writing).

Good biography (which is actually quite rare in my opinion) and good narrative history (Churchill, Paul Johnson, and John Lukacs are the models) always draw near to fundamental questions of human nature and human action.

“Good biography . . . and good narrative history . . . always draw near to fundamental questions of human nature and human action.”

—Steven F. Hayward

Any titles you were once fond of but which you can no longer stomach?

Not completely. As a high school student I was much taken with Francis Schaeffer, and when I read him now I recognize how superficial he is on so many things (and wrong here and there, such as on Thomas Aquinas), but I think he was essentially correct in his conclusions and general disposition, so I still hold him in high regard.

Other authors I once devoured I now find more difficult because I read more slowly and demand more clarity. Eric Voegelin is a good example. Aspects of this thought—and even a lot of his custom terms—now seem opaque to me, though forty years ago I thought I understood him clearly. In general I’ve become more exacting in what I demand from writers in terms of clarity and accessibility.

I’ll add one other perhaps controversial opinion. I wonder if I would like Lord of the Rings if I read it for the first time now. Instead I read it as a teenager, and was completely charmed, as one should be. On rereading it more recently I still delight in it because it takes me back, but I also notice some flaws in the whole scene that I didn’t in my teen years.

I’ll add that I’ve long said that if a teenager reads Lord of the Rings, they become a Russell Kirk-style, traditional conservative, but if they read Ayn Rand, they become a libertarian. I have never liked Rand’s writing style, even if I think she was right about a number of things today.

“If a teenager reads Lord of the Rings, they become a Russell Kirk-style, traditional conservative, but if they read Ayn Rand, they become a libertarian.”

—Steven F. Hayward

Do you see any real gaps in your collection? What’s missing based on current interests or future projects?

Not quite enough literature, both classic and worthy modern novelists.

Do you have any advice for anyone seeking to build a working library of their own?

I’m tempted to say “Don’t.” But not really. A practical necessity: an indulgent and understanding spouse. Also a strong back (because you’ll likely move more than one, and book boxes are heavy). I do go with the general advice C.S. Lewis had, which was something like (going from memory): “Your book budget should be one of the larger items in your household budget.” I spend more on wine now, but book acquisition is still a priority.

Final question: You can invite any three authors from your library for a lengthy meal—and you’re doing the cooking. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

Answer I always find these hypotheticals difficult because I can think of so many possible combinations. I limit myself to just two: How about Churchill, Lincoln, and De Gaulle to ponder the problems of modern political rule and action in a crisis. The other trio would be Aristotle and Aquinas (to argue over their differences) with Leo Strauss along to egg them on.

Thanks for reading. Please hit the ❤️ icon if you enjoyed the piece. And while you’re at it, spread the love and share it with a friend!

If you’re not a subscriber, take care of that now. When the next free review or essay hits your inbox, you’ll be glad you did.

Make sure you also check out my interview with bibliophile and collector Stuart Kells:

Thanks for this one, and particularly the photos.

One of my pet peeves re: articles like this one is that the pictures of the subject's library will generally show a wall of books, but seldom are the pictures focused enough to let you see what's actually on the shelves. Nice to be able to see a number of the titles (which have reminded me of other things I've meant to read... more expense...).

Thanks again.

That house is so lovely for a reader. I am glad he let you show the photos.