Take You Higher—and Then What?

The Perils of Personal Choice: Reviewing Sly Stone’s ‘Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)’

Most people misunderstand California. For one thing, it’s bigger than Los Angeles. When I moved to Tennessee twenty years ago and mentioned my prior home, everyone assumed I meant LA. But Northern and Southern California differ in significant ways.

“Northern California is like Missouri,” as my psych prof at Sierra College once said, “but with hippies.” It’s reflexively independent, even libertarian, and everything hums with latent possibility. No surprise the region birthed the Whole Earth Catalog, Silicon Valley, and the Cato Institute.

It’s also a land of immigrants—and I mean from all over the U.S., not just abroad. Thanks to the Gold Rush, Great Migration, and general allure of the region (which seems to be fading right now), California is a mashup of disparate cultures shaken free from their roots and transplanted in individualist soil.

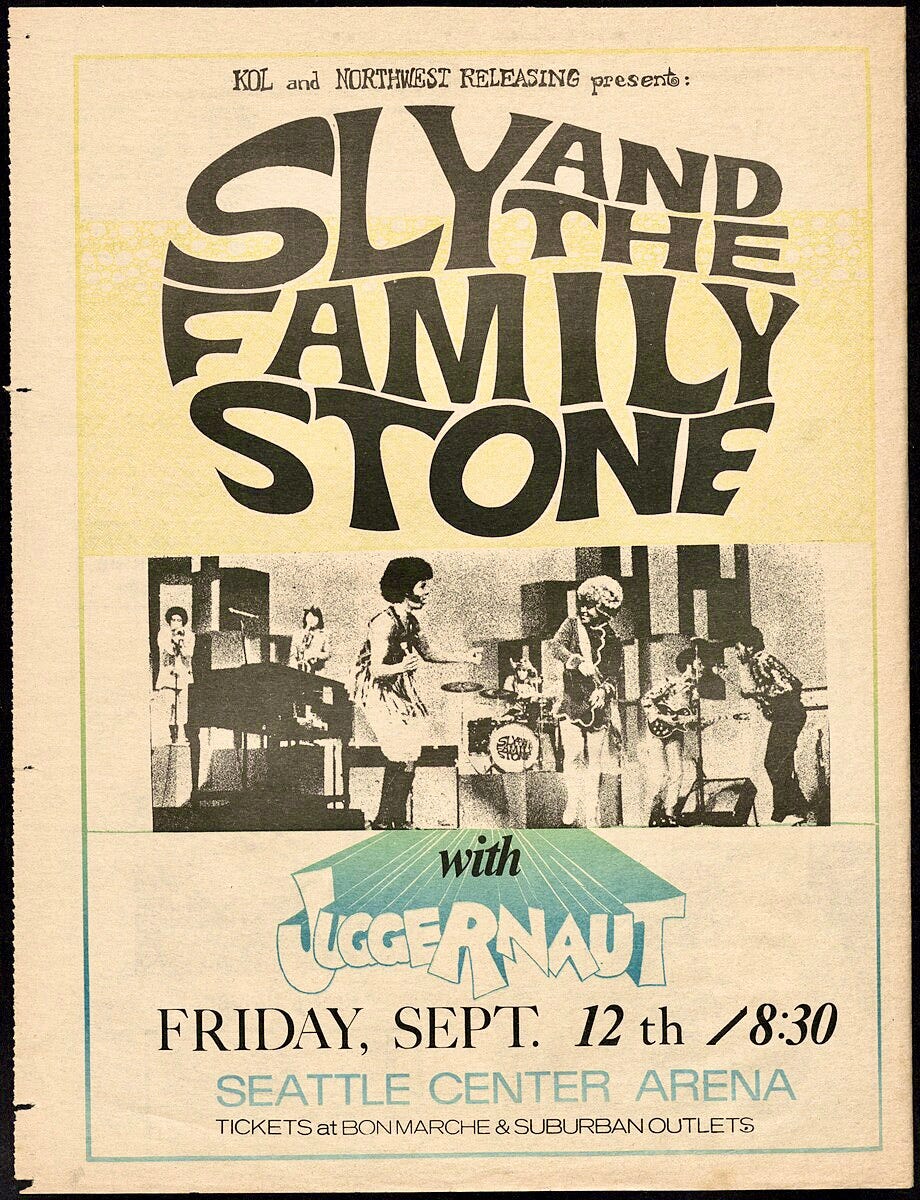

Had Sylvester Stewart stayed in Denton, Texas, where he was born, it’s impossible to imagine his transformation into Sly Stone—the principal songwriter, arranger, and frontman for Sly and the Family Stone, the R&B/funk band popular in the late sixties and early seventies.

That magic trick required moving to Vallejo on the northeast of the San Francisco Bay Area when Stone was just a child. And like any magic trick, Stone’s new memoir, Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again), shows you enough to keep you guessing.

Documenting the Source Code

Christianity fit well in the family’s luggage. Early in the book Stone randomly remembers a Bible verse, John 3.1–2, and shares it from memory. “Why that verse?” he asks on the readers’ behalf. “Can’t remember. Maybe it’ll come to me tomorrow. . . .” It’s good to know we’re in unreliable narrator territory. Not that unreliable equates to insincere—that never really feels in doubt.

Stone’s family called the Church of God in Christ their spiritual home. It was, as he says, “a Pentecostal denomination with roots in Tennessee, only a few decades old at that point but gaining steam.” While Stone eventually stepped away, his early involvement in the church is less surprising than you might think—than I certainly thought.

When I mentioned his religious upbringing to my friend

, he pointed me to Sister Rosetta Tharpe. “The gospel music of the ’40s, maybe most exemplified by Sister Rosetta Tharpe, helped make the rock ‘n’ roll and R&B blueprint,” he said. “Chuck Berry is T. Bone Walker and Rosetta Tharpe with lyrics about cars and teenagers. Jump blues plus gospel plus post-World War II economics equals Chuck.” (It wasn’t Marty McFly after all!)James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Al Green, B.B. King, and Tina Turner—not to mention Elvis, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins—were all raised Pentecostal as well. And Sister Rosetta? She also belonged to the Church of God in Christ.

There’s a through-line, and the influence goes beyond the music to Stone’s lyrics. In the song “Fun,” he paraphrases Jesus’s citation of the Golden Rule: “Sock it unto others as you would have them sock it to you.” And in “Stand!” he sings,

Stand

There’s a cross for you to bear

Things to go through if you’re going anywhereStand

For the things you know are right

It’s the truth that the truth makes them so uptight

These are R&B and counterculture anthems (“Don't you know that you are free?/Well, at least in your mind if you want to be”). But they’re also secular gospel songs with all the musical and lyrical source code for those with ears to hear. And the same is true for other numbers, such as “Everyday People” and even “Loose Booty,” which uses the names of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the Book of Daniel in a pulsating chant.

Does Stone comment on these vestigial forms? Not much and only in passing; it turns out Little Richard and Sam Cooke also started out singing gospel. But, then, there’s a lot he leaves unsaid. And as he also sang in “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again),” the song from which his memoir’s title is drawn,

Thank you for the party, but I could never stay

As I read the book my mind kept returning to that line. It exposes a thematic undercurrent about withdrawal—not only from the church but also from the stratosphere into which he launched himself and his band.

But First, the Party

The most exciting part of the book is the buildup of Stone’s career, the formation of the Family Stone, and their subsequent success. Stone’s family was musical. “There were seven of us,” he says, “and the eighth member of the family was music. . . . Music was as much a part of our home as the walls or the floor.”

Stone’s first solo was singing on stage at church as a child. He started playing drums and then guitar. Soon he knew his way around the bass and keyboard, too. Bored at school, Stone’s mind was consumed by music. He began composing, playing in bands, wowing audiences at gigs.

He studied music theory at Vallejo Junior College but quit school to work in radio, a job that cracked open the music business for him. He started writing and arranging for a small record label. He even had a single float up the local charts. It was all prelude to assembling the Family Stone—a bit of a curiosity for the day in that the eventual septet included black and white members, men and women. Stone even had room for some siblings: brother Freddie played guitar and sister Rose sang and played keys.

Epic Records released their debut A Whole New Thing in 1967, and the band immediately built on momentum. A few months later they released their single, “Dance to the Music,” the success of which ignited their upward trajectory. The album Dance to the Music followed in 1968, and so did Life. The next year, the band released Stand! and played Woodstock, exciting the crowd with “I Want to Take You Higher.”

Sly and the Family Stone was one of the biggest acts going—and then the cracks began to show. Stone would show up late to gigs or storm off stage when the equipment wasn’t just the way he wanted. Worse, the followup to Stand! was delayed and delayed again.

When There’s a Riot Goin’ On finally hit in 1971 observers might have assumed all was well. The record hit Billboard’s pop and soul charts, and the single “Family Affair” went to No. 1. The truth was, however, that the band was beginning to fray. To invoke the observation of another memoirist, Mary Karr, the Family Stone was like all families with more than one member: dysfunctional.

After Higher, Then What?

Is there a cliche more worn out than a rock star faltering because of drugs? It’s easily invoked in the case of Sly Stone. Safe to say: There was far more hippie than gospel in the mix after a while. In some ways cocaine and angel dust become the big characters in Act 2 of the Family Stone tragedy, but drugs might prove too easy an explanation.

Stone mounts no defense for himself in this period, just tells the wild stories—including one of escaping a freebase explosion with better luck than his friend, comedian Richard Pryor.

Still, the story of dissolution that emerges seems less about drugs and more about Stone’s personal unpreparedness for fast money and fame in a world of hangers-on and enablers. His home life was pure chaos, and the music began to suffer as the distractions mounted. The decline wasn’t immediate. Two more albums came in 1973 and ’74, each with hits, but nothing later would rise to the band’s prior success.

The group formally broke up in 1975 and later reformed, at least in name, with different members. But every album after ‘74 was really Stone alone with an array of backing musicians. The problem? He couldn’t even keep himself together any longer, let alone a band. Turns out a family of one can be dysfunctional, too.

That said, the problem with simplistic dissolution narratives is they leave out too much of life. Stone, for instance, spoke to hot-button racial issues from the beginning and debated in public and private on civil rights. He relates his confrontation with Muhammad Ali over the topic on national television and also shares how he resisted pressure from the Black Panthers to fire the white members of his band. Did Stone’s more openhanded perspective on racial reconciliation stem from his individualist, Californian upbringing?

Sadly, such positive moments can’t offset the darker chapters, marked by divorce, isolation, impoverishment, and artistic futility.

You Can Make It if You Try

If you charted Stone’s discography, you’d see a steep downward slope after the seventies—a long, mostly flat tail in which little happened. The memoir makes it sound as though he was busy working, writing, and recording in his mobile studio or borrowed apartments the entire time, but there’s little to show for it and nothing that rises to the level of his early power and ingenuity. “You can make it if you try,” he sang in 1969. A decade later, Stone wasn’t trying too hard anymore.

Could it have gone another way? Stone’s brother and bandmate Freddie found his way back to church. In fact, he’s now a Church of God in Christ pastor. The same freedom that permitted one path paved the other as well. The outcome could have differed for Stone, but that wasn’t the song he wrote.

Then again, Stone’s not done yet. There’s still plenty of music to play, even if these days it mostly involves teaching his grandkids. And you never know just how far Sister Rosetta can reach: In the second to last page of the narrative, Stone mentions “watching gospel choirs on YouTube, and the sermons that go with them.”

Redemption can look curiously Californian at times as well—a little different for us all.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

The story of the effects of the Pentecostal movement on popular culture has never been fully explored. But any translation of religious ideas have to take this influence into account. Add to that the emphasis on feelings and a desperate hunger for intimacy and you have the stew that birthed the Woke movement as well.

“Turns out a family of one can be dysfunctional, too” This! In some ways, I feel it can be worse - especially when Stone’s family had lived and worked together, he'd lost the familiarity of the church too.

I love how the book (and your blog) ends in hope - there really is so much more music to play. A lovely, contemplative piece, Joel. Thank you for sharing with us!