Seeing Goodness More Clearly

Shemaiah Gonzalez Talks about Fighting for Joy, Making Life Work as a Writer, More

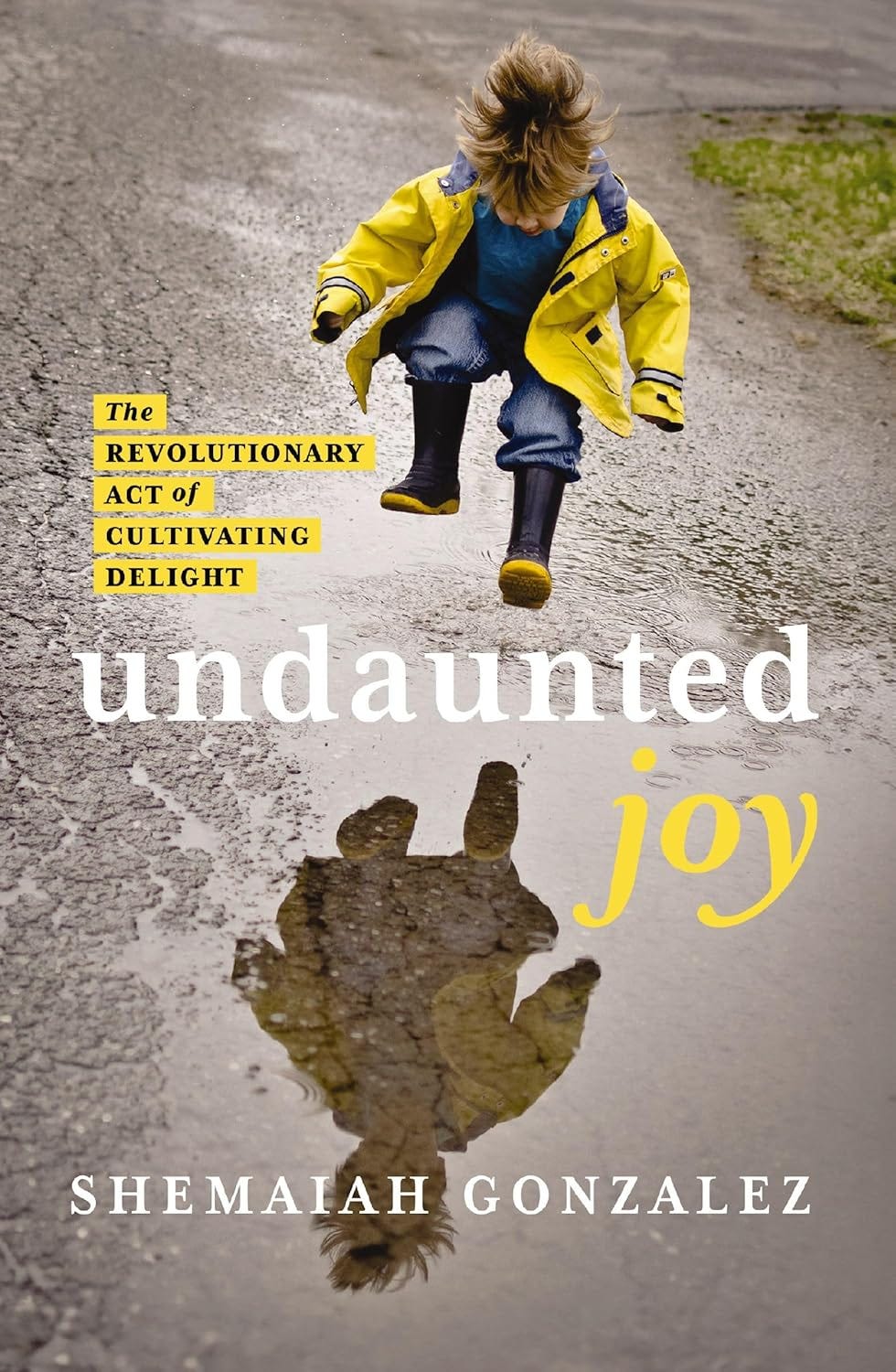

I met the writer Shemaiah Gonzalez on X (still Twitter in those days, I think) and followed her to Substack where she began writing a newsletter on joy. That project grew into a full-blown book earlier this year, Undaunted Joy: The Revolutionary Act of Cultivating Delight.

Readers of Miller’s Book Review might recall Gonzalez’s delightful essay about reading classic novels every summer with her sons. She was nominated for a 2020 Pushcart Prize for her flash nonfiction essay “Dios Mio” in Whale Road Review, and Pope Francis selected her 2018 story about her college English professor for inclusion in his book Sharing the Wisdom of Time.

Gonzalez’s essays have appeared in America Magazine, Ekstasis, The Curator, Loyola Press, and elsewhere. She earned an honorable mention in the 2021 Catholic Press Awards and third place in the 2023 Catholic Media Awards for her “God in the Ordinary” spiritual life column in Northwest Catholic. A Los Angeles native, Gonzalez lives in Seattle with her husband and two sons.

Here we talk about—naturally—joy and the challenges and rewards of life as a writer.

Your book Undaunted Joy has a bold subtitle: The Revolutionary Act of Cultivating Delight. Why do you frame joy and delight in such radical terms?

Our society seems to reward those who build bonds among negativity and victimhood. Any of us with a social media account can see how even our algorithms reward this. It’s all we see. To cultivate delight, when the culture around us is hard set against it, is revolutionary. You will not get rewarded for it in our culture, but you might just save your soul.

Many of us think of joy as an emotion that just hits us or doesn’t. But you treat it as something we can actively cultivate. What do you mean by that, and how do we begin?

Joy has not been my default. I’m a writer for goodness sake! I remember my father had the family take personality tests one evening in my childhood. I tested as a “melancholy choleric.” I was around twelve or thirteen at the time and I thought to myself, “Yep that sounds about right.” But there were some life events, that I share in the book, which jolted me out of despair.

I realized I could not live this way anymore. So, I started small. I suggest everyone start small. Life doesn’t give us a whole lot of huge joyful moments: birth, marriage, graduations, and so on. Life is not one big party. But when you start being grateful for, and taking delight in, small things, you find yourself rewiring your brain and looking through life through a new lens—until it is contagious.

“Joy has not been my default. I’m a writer for goodness sake!”

—Shemaiah Gonzalez

Why is joy so hard? It feels easily crushed by deadlines, bills, or (God help us) the news cycle. What are some practices or habits that make delight more durable in the face of ordinary life?

Joy is hard because it is countercultural. Even when you see the word tossed about in society, it is a weak, diluted joy. Joy is transcendent. It is from God. It is Him, peeking from behind the curtain or veil to reach out to us.

The book is not didactic, in any way. I simply tell stories from my life and how they help others to see the goodness in their own, but some practices that will help you see this delight range from simply turning off the news or not scrolling, learning how to be comfortable with silence, and paying attention to the things that delight you.

So much of a joyful life is giving yourself permission to follow that which is beautiful, good and true.

“So much of a joyful life is giving yourself permission to follow that which is beautiful, good and true.”

—Shemaiah Gonzalez

In the book, you suggest that joy isn’t escapist—it’s a way of engaging the world more deeply. Talk to us about the role of delight as a form of resistance or even resilience.

In Undaunted Joy, I tell various stories of others who found joy in the darkest of places: a WWI trench, a concentration camp, or the story of St. Paul writing a letter about joy during house arrest. To not let fear or anger have control over you in even these dark places certainly seems like a form of resistance. If I can read stories of that, I think I can find joy in my pretty cushy, drama-free life.

Isn’t this what we are here for? To engaging the world more deeply? To do this, we must be intentional about where we spend our attention. I say this knowing how difficult that is. I just spent the morning doomscrolling until my phone overheated and I realized I had a problem.

We have to have a clear focus. “Where our treasure is, there also lies our heart.” I want to redirect my gaze so that my mind is full of goodness when I fall asleep at night and those first waking thoughts in the morning.

The Substack world will probably be interested to know that Undaunted Joy began as a newsletter. Can you tell us that story? Describe the journey from email inbox to bookstore shelves.

Yes! It all started as a Substack. As a spiritual practice I wanted to see if I could write about where I found joy that week, even if things were hard or I was grouchy, in less than 500 words. I put it up on a Substack to see if anyone wanted to come along for the ride, and it turned out they did!

A few of the essays in the book started out as Substack posts and where then fleshed out into a deeper or sometimes sillier version in the book.

My agent and I put together a proposal and shopped it around. Many were interested, but I wanted to make sure that the voice kept its literary and inner world focus, as opposed to “365 days of joy” or something like that. Zondervan understood my vision and let me keep it, so I went with them. It was the most beautiful editing process. Editors are a gift.

You’re a working writer. How has your own pursuit of delight shaped your writing vocation—and vice versa?

I’ve been fairly limited on what I will write about. I write about faith, art, literature, storytelling, and where God is present in all of those. I do not write about politics. I am certain I would have more work and make more money if I did, but I feel it is my vocation to intentionally put out work that is pleasant.

I want to help others to see goodness more clearly. When things get difficult as a working writer, I try to remind myself of what my focus should be. Yes, I need to pay some bills but most importantly, I want to point others towards God. I do not want to comprise my soul to get more work. It is a vocation.

“I want to help others to see goodness more clearly. When things get difficult as a working writer, I try to remind myself of what my focus should be.”

—Shemaiah Gonzalez

Freelance writing can be precarious. What’s your advice for others trying to scratch out their own place in the ecology of the written word?

It is extremely precarious. For me, the balance has been to have another streams of work. I teach, am a writing coach, and do speaking events. This has helped. But I must be honest too. In the last few months, all my paths of freelance work have gone dry. Several 100-year-old publications that I wrote for have dissolved. I see many of my friends aiming for the same writing jobs. There is simply not enough work, and I do not want to be competitive.

My outlook on Christian publishing is that it must be viewed as abundant and generous. We are here to uplift voices that are good and true and beautiful. I don’t want competition to come into the equation. So for right now, I am open in freelancing—using this time to gather seeds for my own writing and uplift the voices I am grateful to see out in the world.

Who are the writers, thinkers, or even personal mentors who taught you how to notice delight?

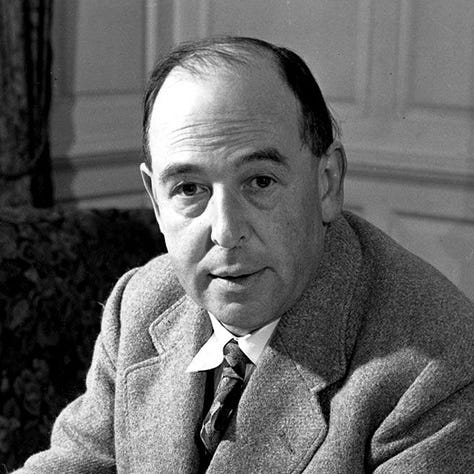

So many and I return to them whenever I get stuck. I realize that C.S. Lewis is where it all began. First in Narnia tales and then as I grew up and read his theological texts I wanted to know more.

Finding Brian Doyle was a game changer for me. I will never write like Lewis; Doyle made me understand there was space for someone like me in the writing world. He could write about anything and turn it into something profound and holy.

Poet Ted Kooser does this with his poetry too. Whether he writes of watching an elderly couple share a sandwich or his dog on a cold day, you realize life is good, you simply need to learn to see again.

Turning to literature, in your chapter on books you mention identifying with various characters. Who are some characters you find that exemplify joy and delight—or at least the struggle for it?

It is October so I am reading Anne of Green Gables again. I write about her in that chapter. I was a lonely child, both at home and at school. I was also a redhead. A teacher gave me Anne and told me I reminded her of Anne. When I read the entire book that evening, I felt as if my teacher looked into my very soul. It was disarming!

I always loved stories both in childhood and as an adult, where characters faced difficult times but did not let it deter them from the truth of their identity. They did not waver or compromise. Jane Eyre is one of my favorites. Reading Corrie Ten Boom, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, emboldened me.

And in Undaunted Joy, I take another look at Pollyanna, a character who gets a bad rap. She is not toxic positivity: she is a little girl who lost her parents, is taken in by an aunt who makes it clear she will not love her, but also refuses to be a victim. She changes the culture of the entire town with her determination, grace, and joy. Oh, and she’s eleven!

Can you walk us through your own writing practice? What rhythms or rituals help you sustain your work?

Exercise and prayer are such an important part of my writing practice. I begin each day at the gym. I listen to worship music as I stretch, I pray for my enemies while I run, and listen through the Bible as I lift weights. When I return home to write, all seems possible after that. I work on writing projects in the morning when my mind is sharper, and I read in the afternoons . . . when my mind is a little more, shall I say, relaxed.

Right now, I am between projects. I actually have nothing on the table until January. So I am gathering seeds. This is the delicious part of writing, to simply be able to follow your curiosity and delight and see where it takes you.

I feel like a kid again. I try to sit with some music, art, and words each day and see where they take me. I did this before Undaunted Joy and became obsessed with Gustav Mahler and Vincent Van Gogh. So much poetry made it into the book because of this seed-gathering time too. It’s a time when I give myself permission to slow down. This does not come naturally for me but once I find the new rhythm, I realize, it is what my soul longed for all along.

“This is the delicious part of writing, to simply be able to follow your curiosity and delight and see where it takes you.”

—Shemaiah Gonzalez

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a long meal to discuss all possible angles of joy and delight. Neither time nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and what would that conversation sound like?

This was such a fun question to think about. Because you said, language would not be an obstacle, I would want to invite father of the essay, Michel de Montaigne. I adore his meandering essays. I wish we were allowed to still write like this. He was knowledgeable and thoughtful about so many things, but also hilarious.

I would invite Charles Dickens. He knew how to work a stage and tell a story. His insight into the hearts of men was unmatched. I think he would make a fine dinner companion.

Lastly, I would invite Evelyn Waugh who wrote one of my favorite books ever, Brideshead Revisited. Of what I have read of his life, he was an absolute maverick. He loved his friends deeply. We share a Catholic faith which I would love to talk to him about more—and he’d bring the gin.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon, share it with a friend, and 💬 discuss it in the comments below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

Read about Shemaiah Gonzalez’s delightful summer bookclub with her boys:

And make sure to tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, and discover the preorder bonuses!

Thank you for the interview, Joel and Shemaiah! Here's a quotation from Waugh about sloth and joy that I came across in my research last week: "The malice of Sloth lies not merely in the neglect of duty (though that can be a symptom of it) but in the refusal of joy. It is allied to despair." From his essay on Sloth, first printed in the Sunday Times, 7 January 1962.

Thanks for this, Joel! Just ordered a few copies of Undaunted Joy for our bookshop.