Shaped—and Misshaped—by Our Parents

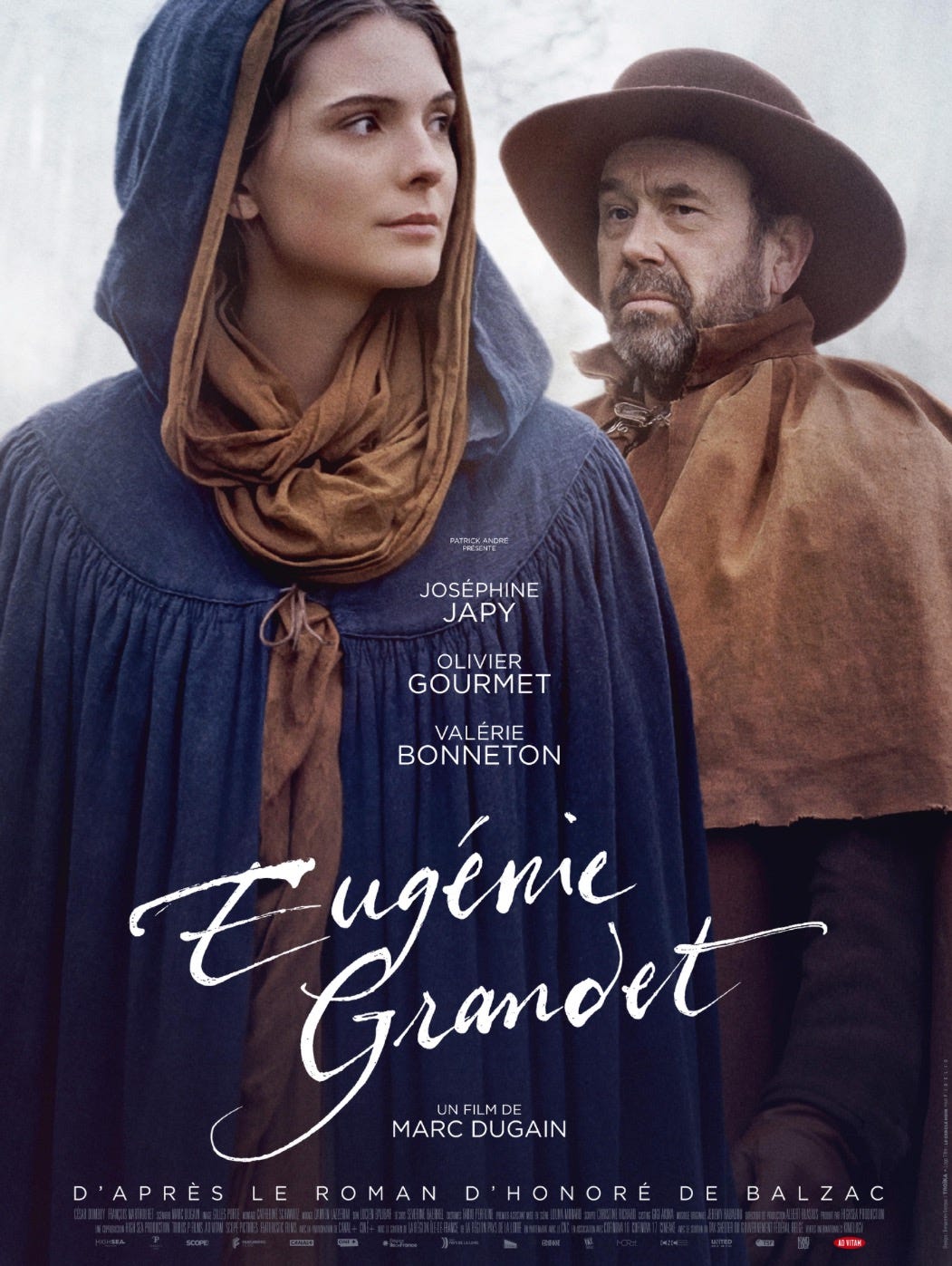

Reviewing ‘Hard Times’ by Charles Dickens and ‘Eugénie Grandet’ by Honoré de Balzac

We are shaped and misshaped by our parents. It’s impossible to avoid the thought when reading Hard Times by Charles Dickens or Eugénie Grandet by Honoré de Balzac. Both books pair doting daughters to domineering fathers, living with passive, submissive mothers. What could go wrong?

Demanding Fathers

Balzac’s Félix Grandet is a miser, comically so, devoted more to gold than his wife and daughter Eugénie, though he shows them affection and concern so long as it doesn’t conflict with his purse. He governs his home with a firm hand and tight pockets. Unable to light fires to keep warm or buy candles for extra light, for instance, his family suffers deprivation despite the wealth accumulating in Félix’s study—a haven to which he regularly retreats to count his coins. “Nobody in that house full of gold ever saw a sou lying about,” says Balzac. Félix would rather walk around broken stairs than fix them to save the money.

Dickens’s Thomas Gradgrind, the headmaster of a school, is committed to a regimen of realism and discipline. For Gradgrind the world is a syllogism, all its details sensibly reduced to rows and columns in tables of digestible data. “Now, what I want is Facts,” he blurts out in the first sentence of the novel. “Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts. . . .”

But—you object, at least I suppose you would—children will be children. Not if Mr. Gradgrind has anything to say about it! No, sir. When his own children, Louisa and her younger brother Tom, sneak off to a circus, Gradgrind is deeply disappointed.

“In the name of wonder, idleness, and folly!” he exclaims before questioning the pair of prodigals. “You!” he finally says to Louisa. “Thomas and you, to whom the circle of the sciences is open; Thomas and you, who may be said to be replete with facts; Thomas and you, who have been trained to mathematical exactness; Thomas and you, here! . . . In this degraded position! I am amazed.”

Imagination, fancy, play—these carry no importance in Gradgrind’s scheme; in fact, they undermine it and must be tamped down and scraped out.

Devoted Daughters

Both Eugénie and Louisa are compliant and devoted to their fathers—willing to ignore their decrees when strictly necessary but otherwise submissive to their expectations and demands. When we find them, both are also of marrying age, which brings them into bitter paternal conflict, Eugénie early on and Louisa later.

Suitors regularly assail the Grandet estate, as families plump their eligible sons in hopes Eugénie might take a shining to one. She doesn’t. Though Eugénie is young, sweet, and modestly attractive, the men hovering around like a Greek chorus share her father’s prime motive; they want to marry into the family’s wealth, and Félix is happy to watch them all desperately jockey for their piece.

All, that is, but Charles. The son of Félix’s bankrupt and suicide brother, Charles comes to live with the Grandets. Wanting nothing to do with his brother’s financial collapse, Félix plans to ship young Charles off to India to make his own fortune the, er, honest way. But while that plan comes together, Eugénie falls passionately—and unfortunately—in love with her cousin.

The two trade promises, and Eugénie even gives Charles all the gold her father has gifted her over the years to help speed his journey back home to her waiting heart. When her father discovers this betrayal (as he sees it), he banishes Eugénie to her room and cuts off all communication with her. He feels he has been robbed. It takes the death of Eugénie’s mother for the two to reconcile, and even then there’s nothing healthy about it.

Louisa’s deference to her father leads her to accept Gradgrind’s recommendation of a suitor—the significantly older Mr. Bounderby—described by Dickens as

a rich man: banker, merchant, manufacturer, and what not. A big, loud man, with a stare, and a metallic laugh. A man made out of a coarse material, which seemed to have been stretched to make so much of him. A man with a great puffed head and forehead, swelled veins in his temples, and such a strained skin to his face that it seemed to hold his eyes open, and lift his eyebrows up. A man with a pervading appearance on him of being inflated like a balloon, and ready to start. A man who could never sufficiently vaunt himself a self-made man. A man who was always proclaiming, through that brassy speaking-trumpet of a voice of his, his old ignorance and his old poverty. . . . He had not much hair. One might have fancied he had talked it off; and that what was left, all standing up in disorder, was in that condition from being constantly blown about by his windy boastfulness.

Louisa, unable to mount any reasonable objection to the match—romance, love, and fancy having no part of the equation—agrees. Misery predictably ensues.

Acquiescence and Resignation

Both Balzac and Dickens flavor their stories with enough levity and humor to prevent their tales from feeling like tragedies, though Eugénie Grandet veers heavily that direction and Hard Times narrowly avoids the fate.

After the death of her mother, Eugénie acquiesces to her father’s stern ways and, though she adapts them to her gentler and more generous disposition, she reduces herself and stunts her heart. Charles reappears having made his fortunes in the slave trade only to find his uncle has done nothing to help dispose of his father’s mountainous debts. Worse, by then he’s dealt himself out of Eugénie’s love and has little to show for it.

Félix ends his life in a pathetic, comic scene where he thrills as the priest administers last rites, not because his salvation draws near, but because the glint of the crucifix excites his greedy heart: “When the priest put the crucifix of silver-gilt to his lips, that he might kiss the Christ, he made a frightful gesture, as if to seize it. . . .”

Right before he dies, Eugénie asks for a blessing. Instead, Félix tells her to steward his fortune. “You will render me an account yonder!” he tells her and dies.

Finally free, Eugénie nonetheless behaves as though this instruction were binding. She never succumbs to her father’s fatal temptation, but she leads a small and disappointing life in consequence of it. Yes, she indulges occasional extravagances such as paying of Charles’s debts and funding various charitable projects, but she rules her life with the kind of frugality and austerity that would have pleased her father—at the cost of her own aspirations and potential.

Though she maintains something of her own shape, Eugénie dwells in her father’s shadow long after his ghost has flown. Not Louisa. She fights back.

Rejection and Repentance

Someone so self-involved as Bounderby could never love Louisa as she deserves. She quickly realizes this, just as she also realizes the poverty of her father’s worldview—something with which she wrestled since childhood. When another man comes vying for her affection, Louisa finds herself drawn to him and nothing in her inherited philosophy suited to resist him. Remarkably, she does push off his advances and instead throws herself at her father with a desperate accusation.

“Father,” she says, “you have trained me from my cradle?” He answers yes and she continues:

I curse the hour in which I was born to such a destiny. . . . How could you give me life, and take from me all the inappreciable things that raise it from the state of conscious death? Where are the graces of my soul? Where are the sentiments of my heart? What have you done, O father, what have you done, with the garden that should have bloomed once, in this great wilderness here! . . . With a hunger and thirst upon me, father, which have never been for a moment appeased; with an ardent impulse towards some region where rules, and figures, and definitions were not quite absolute; I have grown up, battling every inch of my way. . . . In this strife I have almost repulsed and crushed my better angel into a demon.

Amazingly, Gradgrind hears his daughter and softens his heart. Better to say her entreaty breaks it in a thousand pieces—not just his heart but also his entire way of being in the world. When Louisa finally collapses at the end of her outburst, she falls to the ground. “And he laid her down there,” says the narrator, “and saw the pride of his heart and the triumph of his system, lying, an insensible heap, at his feet.” Unlike Félix, Gradgrind repents—and so dramatically recolors the final third of the book.

Focusing her on the distorting role of parents in the lives of their children, I’ve largely ignored other aspects of these two novels—though there is much to please the reader in them both. The Grandet family maid, Nanon, proves a delightful and amusing character. Sissy Jupe and the circus performers—to say nothing of the blowhard Bounderby—welcome their own spotlight in Hard Times. And Louisa’s brother, Tom, similarly betrayed by his father’s terrible system, succumbs to his own stupidity and provides an added layer of drama to the story—a backdrop to test Gradgrind’s repentance.

As we are all either parents or children, and often both, Hard Times and Eugénie Grandet provide compelling narratives to test our own.

Thanks for reading and shaping the community here at Miller’s Book Review 📚. If you enjoyed this review, please hit the ❤️ icon and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

While you’re here, check these out:

"Gradgrind" is the most outrageously Dickensiest name I can even imagine. But knowing Dickens, I'm sure he has a dozen even Dickensier names buried in his books somewhere. He can't keep getting away with it!

Dickens and Balzac lived at roughly the same time, and hold the same sort of venerated position in their countries' literature. And aspiring novelists would do well to read both of them to learn how to write novels.

They were opposites in other ways, though- Dickens did his writing as a day job, whereas Balzac was a night owl. Balzac was far more of a realist than Dickens and conceived his whole oeuvre as a united work (creating an example for, among others, Zola), while Dickens used comic exaggeration to soften the harder edges of his drama (he was a theatre fan and sometimes acted in productions himself). But, ultimately, they were concerned with making their characters believeable as real people, and, there, they succeeded.