Read Along: Compare, Contrast (Luke 16–John 13)

We’re Reading the Gospels in September. Here’s the Place to Share What We’re Discovering

One of the easiest things to notice when reading the gospels back to back—as we’ve been doing in our September gospel project—is how much they share in common. At the same time, it’s just as easy to see how much they don’t. Each gospel has its own distinguishing features, highlighting the evangelists’ unique perspectives.

This naturally invites a compare-and-contrast way of reading. Take, for example, the question of Jesus’s visits to Jerusalem.

Jerusalem or Bust

In Matthew, he seems to go only once—at the end of his life. Same for Mark. But Luke tells us that Jesus’s family traveled to Jerusalem every year for Passover (2.41) and records three of Jesus’s visits: as an infant, as a boy of twelve, and as an adult during the triumphal entry that Christians commemorate on Palm Sunday; two of those trips were for Passover.

John, however, reports several additional visits, not just for Passover but for other festivals as well:

Passover (chapter 2)

An unspecified feast (chapter 5)

Feast of Booths/Tabernacles (chapter 7)

Feast of Dedication/Hanukkah (chapter 10)

Passover (chapter 12)

The implications are considerable. All four gospels, for instance, depict Jesus cleansing the Temple—tossing tables and chasing out the moneychangers. In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, this takes place at the end of his life, sparking a direct confrontation with the Temple bureaucrats and setting the stage for his arrest and crucifixion.

Curiously, however, John places the cleansing during the first of Jesus’s Passover visits in his gospel (chapter 2). Did such a fiery scene really happen twice? John gives no hint of it happening later. Yet it’s just as hard to imagine it happening once, early on, only to simmer for years despite Jesus’s repeated returns to Jerusalem; wouldn’t the Temple authorities have done something about him then? Or is John deliberately relocating the event to make a distinct point, one unique to his telling?

This is only one of dozens of examples where the gospels diverge, often with significant interpretive consequences. What does it mean, for another example, that Matthew and Luke both include genealogies of Jesus but place them in different locations of their account and present them in different ways?

Such questions preoccupied ancient readers of the gospels as much as they do us. Among them, Eusebius of Caesarea emerges for his distinctive approach to these and related conundrums.

Eusebius Tosses Tables of His Own

As bishop of Caesarea, Eusebius inherited one of the greatest Christian libraries of the fourth century, stocked by his book-crazed predecessors Origen and Pamphilus. One of the books in this library was Origen’s own Hexpla, a copy of the Hebrew scriptures in six parallel columns splayed across the open pages of a codex: Hebrew, Hebrew transliterated into Greek characters, and four separate Greek translations, each with their own style.

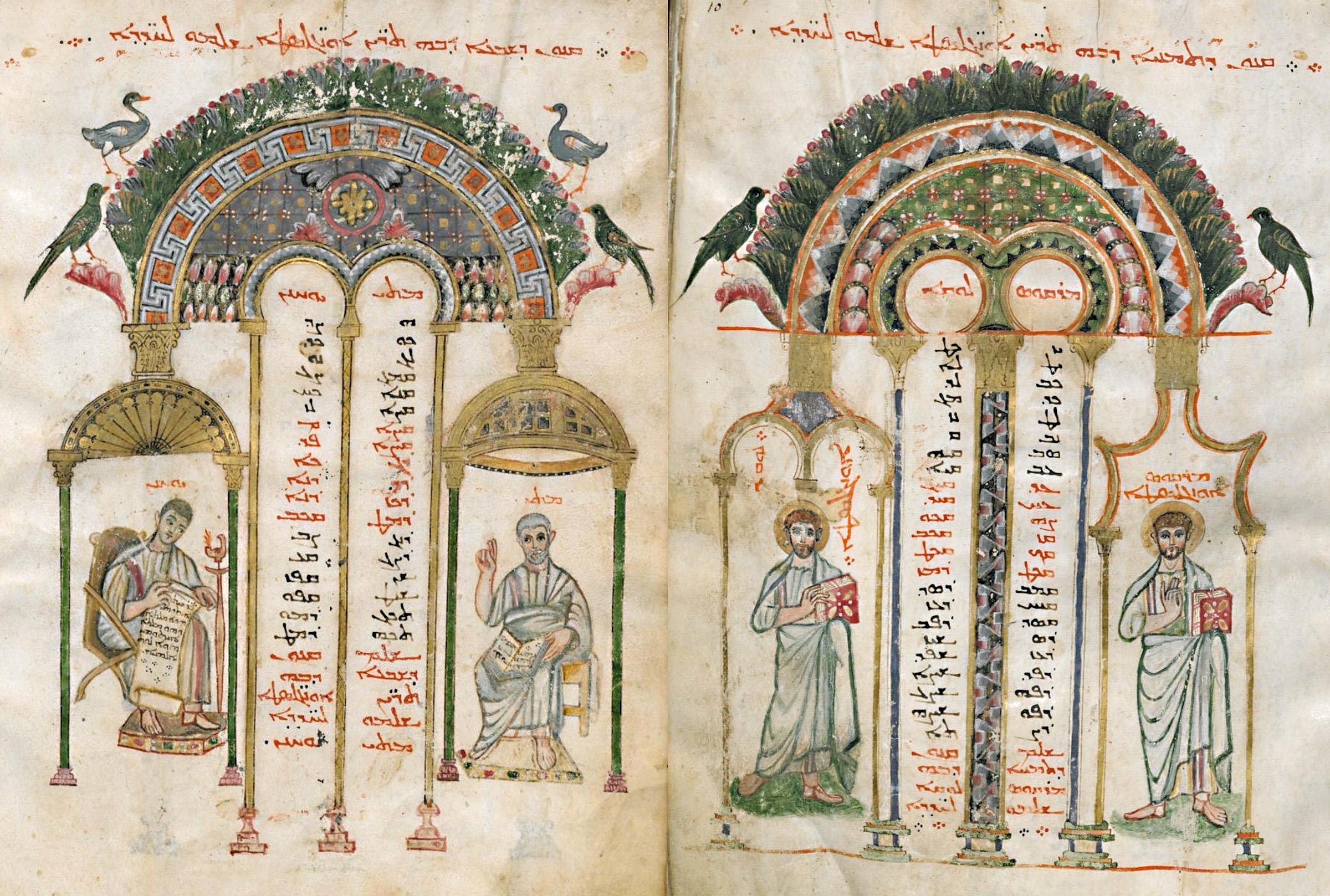

The result? Readers could read down through the passage and across to see the different treatment of the same bits: scripture as spreadsheet.

While tables had been used to display astronomical data and other such information, Origen’s Hexpla was one of the very first books—possibly the very first book—to utilize tables for literary analysis. But the best innovations usually spawn new ones, and Eusebius realized that this same kind of tabular formatting could help him make better sense of the similarities and dissimilarities of the gospels.

Long before the medieval divisions of the scriptures into chapters and verses, Eusebius divvied up the gospels, arriving at 1,162 sections in all: 355 from Matthew, 232 from Mark, 343 from Luke, and 232 from John. He then numbered the individual bits and pieces and plotted them in ten separate tables to track convergences and divergences across all four gospels.

The first of these tables, Eusebius explained,

contains numbers in which the four, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, have said similar things. The second, in which the three, Matthew, Mark, Luke [have said similar things]. The third, in which the three, Matthew, Luke, John [have said similar things]. The fourth, in which the three, Matthew, Mark, John [have said similar things). The fifth, in which the two, Matthew, Luke [have said similar things]. The sixth, in which the two, Matthew, Mark [have said similar things]. The seventh, in which the two, Matthew, John [have said similar things]. The eighth, in which the two, Luke, Mark [have said similar things]. The ninth, in which the two, Luke, John (have said similar things]. The tenth, in which each of them wrote uniquely concerning certain things.

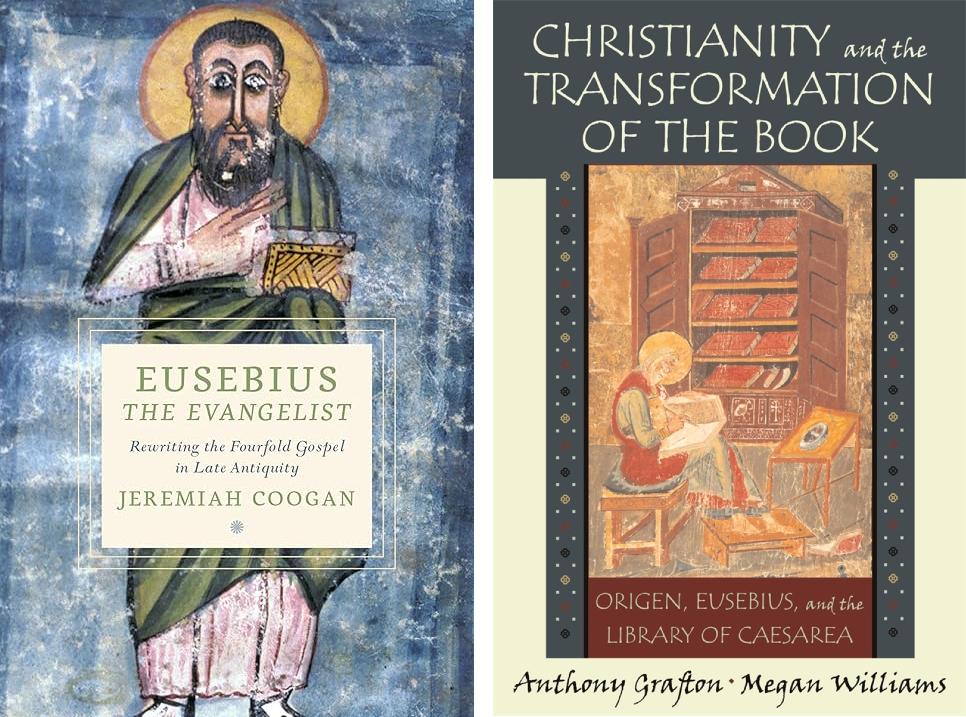

Readers could then, while marinating in a particular passage, bounce to the relevant table and see how the other evangelists treated the same story—or if they did at all. More importantly, they could compare, contrast, and reflect on what similarities or dissimilarities might mean. “One can think with a table,” says Jeremiah Coogan in Eusebius the Evangelist.

Given how familiar we are with tabular reference material today, this might fail to impress. Pity. The truth is no one had really seen anything like these Eusebian canon tables before. “The tabular structure of the Eusebian apparatus affords systematic comparison in unprecedented ways,” says Coogan (my emphasis). The cross-referenced tables were, as Anthony Grafton and Megan Williams put it in Christianity and the Transformation of the Book, “the world’s first hot links.” Eusebius’s tables proved revolutionary and helped set the trajectory of gospel study for at least a millennium.

And what about the differences themselves? Eusebius regarded them as evidence of the evangelists’ fidelity. “They were,” he said, “compelled by love of truth to speak in their own way.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

If you want to read along with the September gospel project, here’s the schedule we’re following. We’re almost done! Feel free to adjust it and make it work for you.

Week 1

Sept 3: Matthew 1–3

Sept 4: Matthew 4–6

Sept 5: Matthew 7–9

Sept 6: Matthew 10–12

Sept 7: Matthew 13–15Week 2

Sept 8: Matthew 16–18

Sept 9: Matthew 19–21

Sept 10: Matthew 22–24

Sept 11: Matthew 25–28

Sept 12: Mark 1–3

Sept 13: Mark 4–6

Sept 14: Mark 7–9Week 3

Sept 15: Mark 10–12

Sept 16: Mark 13–16

Sept 17: Luke 1–3

Sept 18: Luke 4–6

Sept 19: Luke 7–9

Sept 20: Luke 10–12

Sept 21: Luke 13–15Week 4

Sept 22: Luke 16–18

Sept 23: Luke 19–21

Sept 24: Luke 22–24

Sept 25: John 1–4

Sept 26: John 5–7

Sept 27: John 8–10

Sept 28: John 11–13Week 5

Sept 29: John 14–17

Sept 30: John 18–21

I’ll be posting a read-along thread every Monday so we can all share what we’re finding as we read. Next week, we’ll cover the rest of Luke and almost half of John. Make sure you leave any thoughts about Luke 16–John 13 below.

Thanks for initiating this reading experience, and for sharing your very astute editorial perspective, Joel. A thoroughly enjoyable and enlightening read. I think I like Luke's telling of the gospel best. He seems so interested in people and obviously considered women's lives important which is pretty remarkable for the cultural and historical setting of the text.

BTW, a friend of mine refers to Jesus' overturning of the tables in the Temple as his "temple tantrum."

My ability to read on schedule was interrupted by eye surgery on Sept. 23. I had got a few chapters ahead, but will have to finish when things get clearer again. After seeing Joel's cartoon about Jesus teaching in 'parabolas,' I started looking for other conic sections. Jesus also spoke in 'hyperbolas' (You strain out a gnat and swallow a camel). I believe Jesus' defense of Mary's anointing in John 12 includes an 'elliptical' sentence. But seriously, today's readers might grasp the figures of speech more easily than Jesus' contemporaries, who seemed stuck on the literalness of the parables.