Questioning the Greatness of ‘Gatsby’

Is ‘The Great Gatsby’ Fitzgerald’s Masterpiece or, as One Critic Says, ‘Aesthetically Overrated, Psychologically Vacant, and Morally Complacent’?

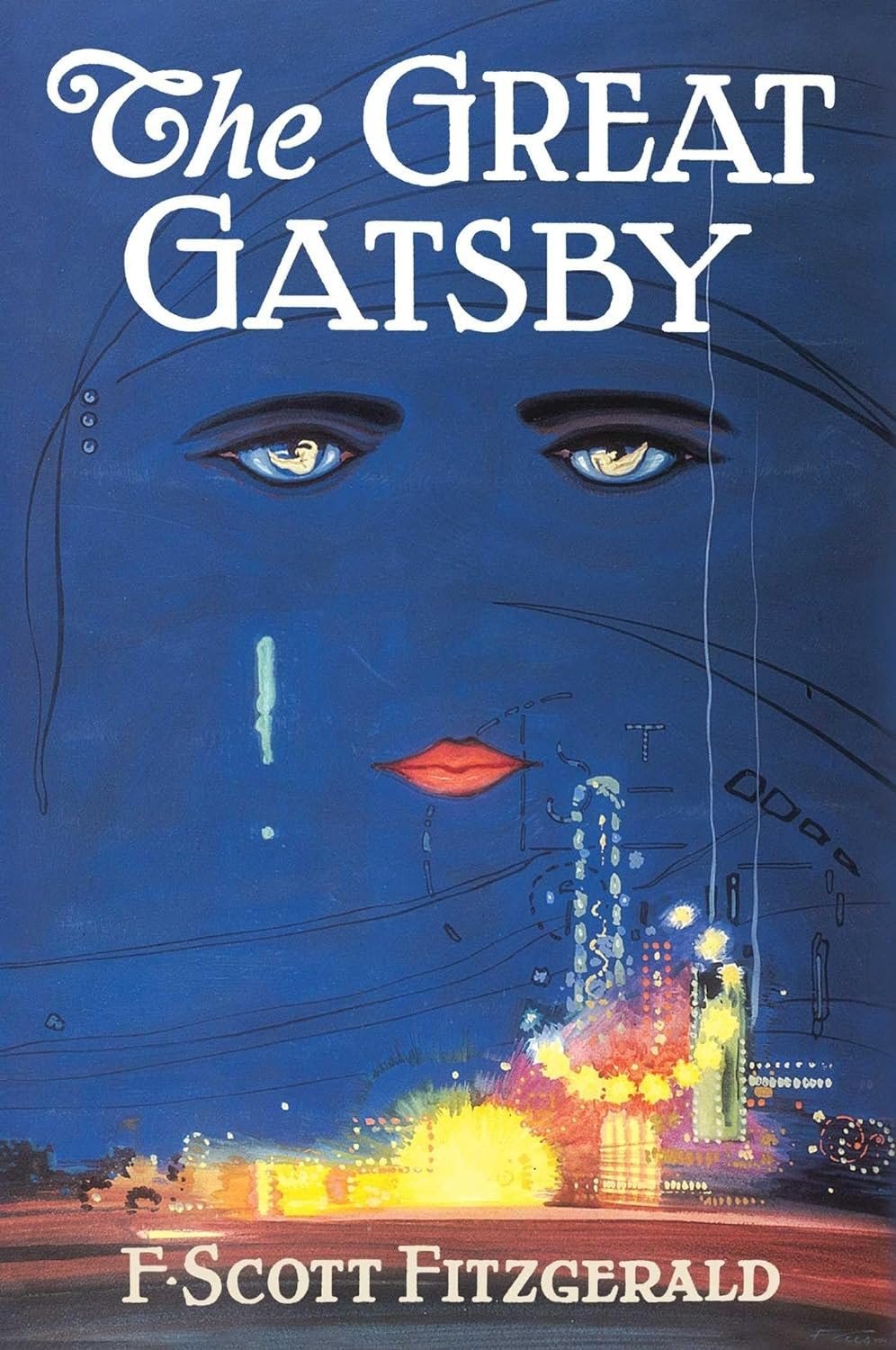

In April 2025, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s immortal novel The Great Gatsby turned 100. What do we make of it? I read it twice last year. I didn’t much enjoy it the first time through but thought I should give it another go. On the second pass, it somehow worked its reputed magic. I still think fondly of that rereading experience.

Coupled with its fascinating backstory, including its Lazarus-like return from the literary nether realm, Gatsby earns its praise. You can find that story here in my review and in another essay on books that fade from public consciousness. But now I want to focus on what others say, starting with Fitzgerald’s foes.

Haters Gonna Hate

Many readers, including critics, can’t find enough plaudits to pile atop Fitzgerald’s novel. Not Kathryn Schulz. “I am in thoroughgoing disagreement with all of this,” she says. “I find Gatsby aesthetically overrated, psychologically vacant, and morally complacent; I think we kid ourselves about the lessons it contains.”

Gatsby hits Schulz as shallow, even childish. “The Great Gatsby is less involved with human emotion than any book of comparable fame I can think of,” she says. Gatsby, Nick, Daisy, and the rest “function here only as types, walking through the pages of the book like kids in a school play who wear sashes telling the audience what they represent: OLD MONEY, THE AMERICAN DREAM, ORGANIZED CRIME.” The central romance? Fitzgerald “constructs [it] out of one part nostalgia, four parts narrative expedience, and zero parts anything else—love, sex, desire, any kind of palpable connection.”

And that’s only the beginning of her indictment. Schulz flags Fitzgerald’s chauvinism, his simplistic view to wealth and class, his humorlessness. She even attacks Gatsby’s famous final line. “I roll my eyes,” she says, and you can almost hear her groan when she does so. Nor is Schulz alone.

Novelist Blake Butler savages the book. Since its publication, he says, “Fitzgerald’s prose seems to have grown bloated, decorously written yet so bland.” The plot is thin, the characters flat (Nick is “human wallpaper”). “I can actually feel myself getting dumber and more mindless as I read it,” says Butler, “almost like suffocating.” Gatsby, he says, has left us with “psychic damage, both literarily and as a culture.” If you read the rest, you’ll need something to wipe up the blood.

Never a gentle critic, H.L. Mencken panned Gatsby when it released. The story was “no more than a glorified anecdote, and not too probable at that,” he said, and excluding Gatsby the characters were “mere marionettes—often astonishingly lifelike, but nevertheless not quite alive.”

Even Bob Dylan, as Daniel Honan points out, takes a swipe at the book’s supposed ability to illuminate the world:

You’ve read through all

of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books

You’re very well read,

it’s well known

But the addressee of “Ballad of a Thin Man,” the mysterious Mr. Jones, hasn’t picked up anything useful in Gatsby. It’s too shallow to reveal anything meaningful about life.

Because something’s happening here

and you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?

Still, Dylan and the rest of the haters must be wrong, no, at least in part?

Another View

One of the reasons Gatsby has endured—besides some extraordinary good luck—is its ability to speak to every generation that picks it up, whether GI’s hunkered in tents between battles in WWII or high-school students grateful one of their assigned readings is so short. Whatever our context, when we peer inside the covers we find a reflection of our world, even ourselves.

Gatsby explains us. Ross Douthat says as much here, specifically how Gatsby reconciles two competing impulses within the American attitude, our idealism and our materialism, especially as they play out amid our struggle to grab what we want in a world of constraints.

There are upsides and downsides to both, and the book lends itself to cultural critique from either direction. Right now most of those critiques are decidedly negative. Constance Grady, for instance, sees the specter of Elon Musk and DOGE in the famous line about careless people: “They smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness . . . and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” And Sarah Churchwell says Gatsby anticipates the rise of President Trump.

Perhaps. That is, in part, because the book can anticipate anything fundamentally American. Gatsby interprets something so essential about the American character it remains permanently evocative.

“While the specific terms of the equation are always changing, it’s easy to see echoes of Gatsby’s basic conflict between established sources of economic and cultural power and upstarts in virtually all aspects of American society,” says Reason editor Nick Gillespie. “Gatsby is the great American novel of the ways in which free markets (even, and perhaps especially, black markets) overturn established order and recreate the world through what Joseph Schumpeter called ‘creative destruction.’”

The language of Gatsby is languid, but the drama it conveys pulses with same energy that powers our individual striving and our cultural dynamism. As a result, the novel has the ability to both evolve along side us and explain our experiences as we go.

A World Wide Open

The slender story bears many interpretations precisely because it’s so slight. What the critics deride as thin in the narrative leaves room for the reader to more imaginatively inhabit the characters and events with their own intuitions and aspirations.

What if, for instance, Gatsby were black? Fitzgerald never actually says anything about Gatsby’s race; we just presume—reasonably enough—that he’s white. But what if he weren’t? What if he were black passing for white, a man on the outs, edging his way in?

High-school teacher Alonzo Vereen found such a reading opened up the story for him and his students. The students in his class—“all children of color living in an impoverished rural community in South Florida, many of them first-generation Americans whose parents had come from Haiti, Cuba, Mexico, or Guatemala”— struggled with the story, its time, place, language. It felt too distant, too unrelatable. But pointing out the racially indeterminate nature of Gatsby offered a way in. “Gatsby’s American identity is so ambiguous that the students could layer on top of it any ethnic or racial identity they brought to the novel. When they did, the text was freshly lit.”

Fitting. In a sense we’re all first-generation Americans, trying to figure out what it means to live in a country that sees personal renewal and the fresh start as a fundamental part of its makeup, that’s constantly changing as creative destruction moves the furniture of our lives.

Gatsby is, of course, a tragedy—but the urge to reengage it, to console us when we lose, to inspire us as we strive, points to a hope that might have eluded its author but which is as relevant now as it was a century ago. Arguably more so.

Thanks for reading! Please hit the ❤️ below and share this post with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

While you’re here, don’t miss…

Actually, Jay Gatsby is a Jew passing as a Christian (his real name being Jacob Gatz). But that was dangerous as a black passing for white in those days.

Fitzgerald's novels all tend to emphasize mood and atmosphere over plot and characters. But his short stories, a field in which he was extremely prolific, are a bit more controlled and allow plot and characters to come to the fore (he had less time and room to move here); they also demonstrate the skills that would end up with him going to Hollywood to write scripts- a movie-like capture of events. Even when he was writing a wild and weird fantasy like "The Diamond As Big As The Ritz", he gave it an undertone of believable reality.

I’m commenting without even reading the article. Take this as a comment on just the headline. I’ll read the article and follow up. Maybe I will regret the comment. Anyway, here goes:

“Aesthetically overrated, psychologically vacant, and morally complacent”.

But what we are talking about is a great American novel that defines the roaring twenties. Gatsby isn’t perfection, it is a time capsule. The above quote, if it defines Gatsby, does so only because it also defines the twenties themselves.

“Aesthetically overrated, psychologically vacant, and morally complacent”.

Yes! Could there be any better summary of the 1920s?

Let’s dive in to the article and find out.