Bookish Diversions: The Puzzle of Publishing

Dueling Takes on the Industry, How the Numbers Really Work, Learning the Trade, Enormous Book Advances, Interview with Yours Truly, More

¶ Dueling takes on the publishing industry. Publishing is a closed book for most. As a result, anything that shines a light on the current state of the trade can prove irresistible. Hence the viral sensation of

’s recent essay “No One Buys Books.” For her piece Griffin scoured the antitrust trial revelations emerging from the thwarted purchase of Simon & Schuster by Penguin Random House, a sale blocked in 2022 by Biden’s Justice Department.The lead line at Arts & Letters Daily summarizes the near universal reception of Griffin’s eyeopening report: “Thanks to a recent antitrust trial, we have a clear look at the business of books. What it reveals isn’t pretty.” One of the juicier bits: “The DOJ’s lawyer collected data on 58,000 titles published in a year and discovered that 90 percent of them sold fewer than 2,000 copies and 50 percent sold less than a dozen copies.”

But not so fast, says author

.¶ A dozen . . . or a billion. People do buy books, says Michel in the aptly titled “Yes, People Do Buy Books.” In fact, based on conservative estimates extrapolated from BookScan sales data, we buy more than a billion books a year. BookScan compiles print sales from recognized book retailers; it’s somewhat incomplete—excluding some stores, plus ebooks and audiobooks—but it’s the best info available. I used it every day when I acquired books at Thomas Nelson.

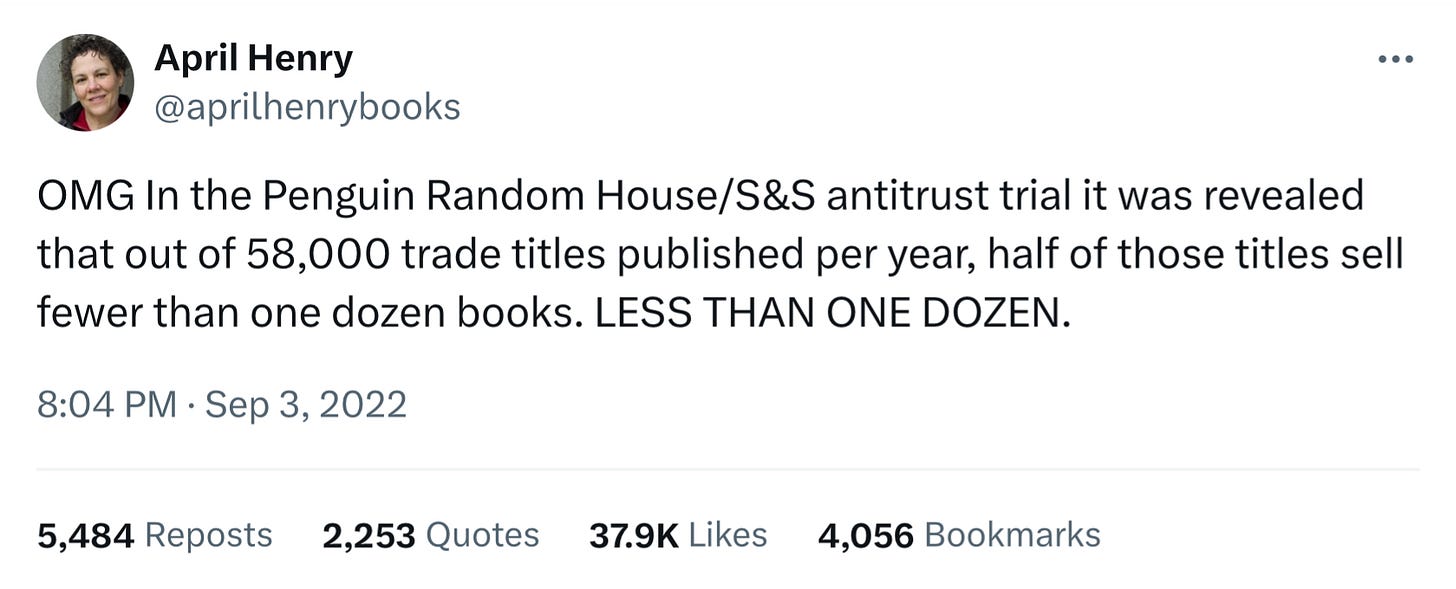

But, you might object, the billion figure is in toto. What happens if we break down the total and look at, say, that stat about half of books selling fewer than a dozen copies a year? Arguments in the PRH/S&S case produced a lot of talk about book sales at the time. As you can see by the number of shares and likes on the tweet below, that stat made an impression on shocked observers at the time.

Turns out the number—or at least the conclusions we’ve drawn from it—is off. Michel actually poked a hole in it two years ago. The issue, he says, depends on what we’re counting as a “book,” as “published,” and as “sold.” It’s squishier than you might guess, and Michel explains how misunderstanding leads our assumptions astray.

What’s more, Kristen McLean, BookScan’s lead industry analyst, crunched the numbers herself and shared her findings in the comments on Michel’s post. She found less than 15 percent—not half—sold fewer than twelve copies. Pulling sales data for nearly 46,000 unique frontlist (new) titles from the Big Five publishing companies (PRH, S&S, HarperCollins, Hachette, and Macmillan), along with several others (Scholastic, Disney, Abrams, Sourcebooks, and Wiley), McLean looked at the last year’s worth of sales. Her findings:

0.4% or 163 books sold 100,000 copies or more

0.7% or 320 books sold between 50,000–99,999 copies

2.2% or 1,015 books sold between 20,000–49,999 copies

3.4% or 1,572 books sold between 10,000–19,999 copies

5.5% or 2,518 books sold between 5,000–9,999 copies

21.6% or 9,863 books sold between 1,000–4,999 copies

51.4% or 23,419 sold between 12–999 copies

14.7% or 6,701 books sold under 12 copies

Those are sobering figures, but hardly dire news—especially when you recall that the numbers represent only frontlist titles over a twelve-month period, not the total number that books sell over their lives. Those numbers are significant. Backlist sales account for about 70 percent of publisher revenues, according to McLean.

¶ How the math really works. What most of these sorts of breakdowns can’t capture is how publishers actually think about the books they acquire. When acquiring a book, publishers model its financial potential. That model helps determines whether a proposed acquisition represents a worthwhile opportunity.

Every publishing house is a bit different but here are the basics, more or less:

Price of the book discounted for wholesale. Retailers purchase books from publishers for roughly half of the cover price.

Forecasted units sold over a twelve-month period. Multiply No. 1 by No. 2 and you’ve got the expected gross revenue generated by the book in a year.

Returns, calculated by percentage of units sold. Retailers won’t keep inventory that doesn’t sell. Subtract this from gross revenue and you’ve got the net revenue.

Cost of product. We’ll leave off other overhead and limit this to just print, package, and design. It’s probably about 10 percent of the cover price. Subtract this from everything above and you’ve got the gross margin.

Sales and marketing. This includes retail placement, ads of whatever kind, publicity, and so on. This is less than you might think. Let’s call it 10 percent of the cover. Subtract this from everything above and you’ve got the contribution margin.

Author royalties. The author gets paid off either the cover price or wholesale price (retail vs. net royalty rate). The rate could be, say, 10 percent of the cover price (retail rate) or 20 percent of wholesale (net rate).

Now let’s imagine this playing out with an imaginary memoir, Lilly Hartley’s Thinking with Cats.

The cover price on the book is $25 for which retailers will pay $12.50.

The various sales channels expect they’ll sell 10,000 copies across their various accounts. Gross revenue: $125,000.

Let’s say 9,000 units find a home, but accounts send back 1,000 units; that comes off the top. Net revenue: $112,500. But of course, there’s more coming off.

It costs the publisher $2.50 per unit to produce the book. That’s $25,000, which comes off the $112,500, leaving a gross margin of $87,500.

It takes money to make money, and sales and marketing will take about $25,000, which also comes off the $112,500, leaving a contribution margin of $62,500.

Meanwhile, Lilly Hartley has already been paid. She got an advance of $20,000, which the publisher recouped within the first year. With nine thousand units sold at net royalty of 20 percent, she’s earned $22,500.

That means the publisher needs to cover the rest of its bills—taxes, salaries, debt expense, rent, HR, lawyers, and so on—with the remaining $40,000.

¶ Budgets and portfolios. A few notes on the above, besides the fact that Lilly Hartley isn’t surviving on her book. For starters, neither is her publisher. If they sign it, Hartley’s memoir exists within a portfolio of properties from which the publisher expects to make a certain amount each year.

How much? The total is usually whatever the publisher made last year, plus a growth rate—maybe 3, 4, 5 percent. That’s the budgeted revenue target. Within a large publisher the total gets broken down across the various imprints. Let’s say an imprint needs to contribute $10 million in net revenue to the total. Then, let’s say McLean’s 70 percent figure is accurate for this particular imprint’s backlist. That means the imprint must produce $3 million in frontlist revenue.

The imprint would need twenty-seven books with Hartley’s same financial potential to make its number. But not all books are created equal. Some have more potential, some less. There’s also a difference between potential and actual sales; some books perform better than planned, others—maybe most others—worse. The success of the imprint depends on how good its bets are. There are multiple points of potential risk, none more risky than the advance.

¶ What makes a book a success?

, an author I’ve read and enjoyed for years, asks and answers that question at her Substack. Largely, it has to do with publisher expectations, communicated in the size of an advance. That advance—royalties paid in advance of actual earnings—is entirely speculative. Griffin compares publishing to venture capital; it’s an apt comparison. “Publishing is,” as McLean says, “very much a gambler’s game. . . .”Publishers use BookScan data to inform those expectations and help determine the scope of the advance based on prior sales by the author or sales of comparable books. (This is where, as Melanie Walsh points out, the incompleteness of BookScan data might prove relevant.)

In our fictional case, Hartley got a $20,000 advance. But let’s say the acquisitions editor had a fourth martini at lunch, the entire financial team was vacationing in Cabo San Lucas, and he paid her $50,000. The publisher would have to cover its overhead with just $10,000; that wouldn’t do. But it could be worse.

Imagine the various sales channel reps were particular taken with cats that season because another publisher had a runaway bestseller with felines in the title and they overshot their projections. Instead of 10,000 units, accounts took just 8,000. And despite the publisher spending the full marketing budget, customers didn’t respond. Returns were brutal; only 5,000 copies actually cleared the cash registers; 3,000 were returned.

Now there’s blood on the ground up to your ankles. With a net revenue of just $62,500, the contribution margin is now only $12,500. Of course, Hartley’s royalty goes down. But—damn that fourth martini!—the advance doesn’t. It’s already been paid. If the editor extended a $50,000 advance, the publisher is out $37,500.

¶ Here’s hoping! The references to venture capital and gambling remind me of this quote from publisher William Jovanovich from his book Now, Barabbas:

Of publishers it may be said that like the English as a race they are incapable of philosophy. They deal in particulars and adhere easily to Sydney Smith’s dictum that one should take short views, hope for the best, and trust God.

¶ Learning the trade. I first read Jovanovich more than fifteen years ago when I was promoted to publisher of an imprint at Thomas Nelson. I’d been a senior editor and then associate publisher for some time before that. I had no formal training—everything I learned was on the job and from various mentors, some of whom were dead.

I read the books of famous publishers and editors hoping to gain some insights into the nature of my job. Two of my favorites were Jovanovich and Maxwell Perkins, who edited authors such as Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe. I learned helpful lessons about acquisitions, marketing, the risks of publishing current events, and more.1 (That last one was especially helpful since my imprint published mostly current events.)

¶ Enormous book advances. What about those huge advances we sometimes hear about? Our fictional Hartley’s original advance was fairly modest. But I acquired books sometimes at ten times that amount and more, sometimes much more. Advances are speculative and based on both the rate and potential sales. When things are sane, that is.

Using our same model above, if the projected sales were 50,000 units Hartley’s potential royalties would be $125,000. An editor could easily justify an advance of $50,000 or $75,000, maybe even the full $125,000. And depending on the circumstances, they might go higher—a lot higher. When an acquisition becomes competitive, publishers bid up the price of the advance. We’re well past martinis at this point; we’re huffing the deal.

What might have begun as a respectable offer of $100,000 in advance could end up at twice that, two and half times that, three times that! The publisher will start by asking sales to goose up their numbers to justify it, but eventually the deal hovers high enough above the surface of the spreadsheet that actual numbers no longer apply. Dangerous statements like “What’s your gut tell you?” are uttered before fateful emails are sent.

¶ Bad news, good news. If you’re interested in how publishing works and sometimes doesn’t, I strongly recommend reading both Elle Griffin’s “No One Buys Books” and Lincoln Michel’s gentle rebuttal, “Yes, People Do Buy Books.” I find this telling, though. However helpful or hopeful Michel’s piece, it’s received just a quarter of the likes Griffin’s has. Bad news travels faster and further than moderately good news, I suppose.

¶ Book culture. I recently appeared on Alan Cornett’s delightful podcast, Cultural Debris. You may recall I interviewed Alan here back in October. For his show, Alan wanted to talk a bit about all things bookish. We discussed culling a library, the merits of audiobooks, reading multiple books at once, and more—including how to think about publishing a book. Is it best to go with a traditional house, self-publish, or try another format than a book? I hope you check it out.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Perkins even shaped my regard for the physical properties of books, for which I advocated at Nelson and which still guides me now. In 1943 he wrote of one well produced volume, “A man who loves books would buy it for its physical qualities alone.” As a book lover, I got that. However, there were few views in publishing less popular in 2007 when I first read those words and, coincidentally, the same year the Kindle hit the market. Regrettably, it was also the same time publishers started referring to themselves as “content providers.”

Perkins kept me sane. I had several conversations with colleagues who were convinced ebooks, fragmented IP, even games were the future of publishing. Perkins gave me the language and the conviction to speak otherwise: “We publish books for people who love books,” I would say. “If we forget that, there is no future.” I was following Perkins. And based on the way it seems to have shaken out, I’d say he won the argument.

Definitely agree that a book lover buys books for physical qualities. I have a very slim book budget, but I will search high and low for just the right edition for a favourite book. First editions are generally out of my price league, but I have sometimes waitex years to find just the right copy.

That brings me to a point about people buying or not books. The publishers don't see revenue from this aspect, so it never gets counted in their records, but it does contribute to the overall economy. It also helps ensure that worthwhile books are not lost by the passage of time, when publishers have moved on to the next big thing. I would not be surprised if used booksales account for a very large percentage of the actual total number of books sold.

"The best way to make a small fortune in book publishing is to start with a large fortune." The most rewarding part of publishing is not the money (although going broke would be no fun) but the experience of fighting to publish a book that had been overlooked by other publisihers and then find that World Magazine said that from its perspective that book was one of the top 100 books published in the 20th Century. I'm thinking of "Idols for Destruction" by Herb Schlossberg, first published by Thomas Nelson. Maybe we do this because of ideas and relationships.