The Long, Bright Shadow of Russell Kirk

Alan Cornett on Kirk’s Penchant for Halloween and Ghost Stories, Plus Other Bookish Diversions

Many will know Alan Cornett as the host of the Cultural Debris Podcast, a show about, as he says, the “flotsam that the culture at large may not value, but some of us in the row boat still do.” Some will also know him as the cofounder of Cultural Debris Excursions, which leads small group trips to Europe and beyond.

Given that Cornett hails from the Appalachian mountains of eastern Kentucky, it’s perhaps not surprising his interests lean toward bourbon, books, basketball, bluegrass, and Wendell Berry.

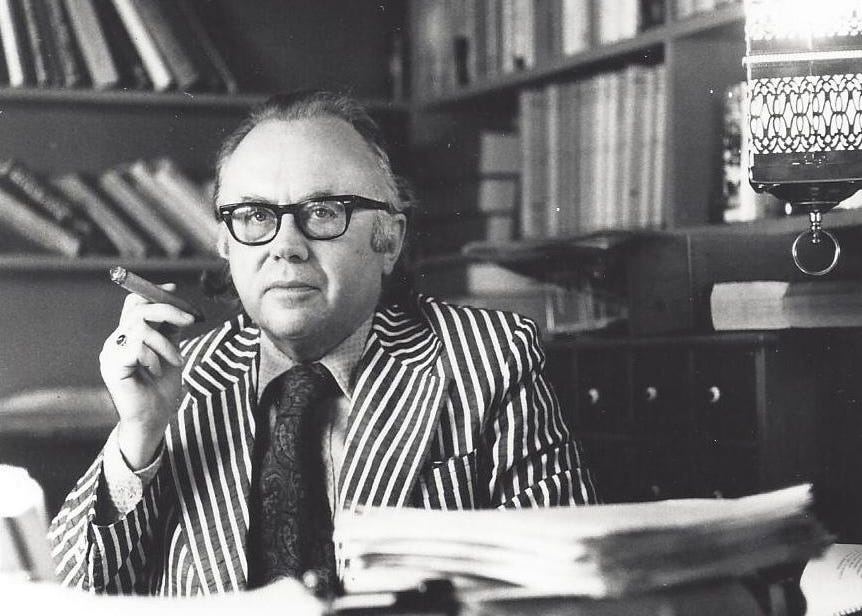

What some may not know is that he was once the personal assistant to Russell Kirk, the so-called father of American Conservatism who, among his many political and philosophical works, penned gothic thrillers and ghost stories and cherished Halloween above other holidays. We talk about that and more in the conversation below.

Some time ago you named October Russell Kirk Month—Kirktober. Who was Russell Kirk and why October?

Russell Kirk was the father of American Conservatism. His classic book The Conservative Mind was a launching point for the post-WWII American conservative movement. He was a founding writer for National Review, founded the magazines Modern Age and The University Bookman, and wrote over thirty books.

October 19 is Dr. Kirk’s birthday, and Halloween was his favorite holiday. I first had the inspiration for Kirk Night on his birthday from the annual observation of Burns Night. Then I decided to dub the entire month Russell Kirk Month.

That Kirk loved Halloween frankly surprises me, though I did know he had a thing for ghost stories and and wrote many. What can you tell us about this side of him?

Dr. Kirk’s ancestors were spiritualists who conducted seances and such. The old house (that burned down in the 1970s on Ash Wednesday) was also haunted by several ghosts, some of which Dr. Kirk himself saw—as well as some of his daughters when they were young. He was a firm believer in the supernatural.

He began writing ghost stories when he was a doctoral student at St. Andrews in Scotland as a means of supporting himself. His story “There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding” won a Hugo Award for best short fiction. He gave up his family’s spiritualism but held to his belief in the supernatural.

You were his personal secretary for some time. I’m always fascinated by the stories of people who facilitate the work of others. What was that like?

Assistant is probably a better term, but duties ranged from retrieving and sorting mail to answering standard correspondence to building fires in the library on cold mornings. My job was to do whatever needed doing to relieve Dr. Kirk (and his wife Annette) from everyday tasks.

His assistants were usually young and between graduate studies, so the Kirks took our intellectual formation seriously. We would have in-house seminar discussions about our own readings and projects, plus you had the priceless opportunity simply to absorb wisdom from Dr. Kirk himself from daily interaction.

What did you learn about him, about the world through him? And what did you learn that might surprise the average person most of all?

Through Dr. Kirk I learned about the real meaning of culture as a lived out religion and the dangers of ideological thinking. Unspoken but apparent was also an appreciation of the good life, which wasn’t a life of extravagance or power, but rather of intellectual leisure combined with family, friends, and active piety. Certainly, the seeds planted during this time bore fruit in my eventual conversion to Catholicism.

A lot of people would be surprised at how funny Dr. Kirk was. He was always ready with a dry quip. He had a great sense of humor.

“He was always ready with a dry quip. He had a great sense of humor.”

—Alan Cornett on Russell Kirk

What contribution could Kirk’s conservatism make to America today? And how would you sell that to someone with (a) more progressive leanings or (b) a more classically liberal/libertarian bent?

A lot of what passes for conservatism today is simplistic sloganeering or merely performative. Dr. Kirk’s conservatism was one that emphasized prudence and rejected ideological thinking. Answers in this world aren’t simple and neat, and there is no Great Solution to our ills in a fallen world.

To the progressive and libertarian both, Dr. Kirk would point to the impossibility of the perfectibility of man and the rejection of history as “progress,” that society must fundamentally have order in order to flourish. Dr. Kirk’s conservatism wasn’t based on political partisanship, but was rather a cast of mind and way of thinking.

If readers are going to give Kirk a try, what’s the most obvious first book they should read? What about the least obvious? What underrated title of his awaits rediscovery?

One of his early books Prospects for Conservatives gives an accessible overview to his vision of conservatism. Politics of Prudence, a later collection of Heritage Foundation talks, is also a nice entry point as it is topical and the essays are more easily digestible. A slim later volume that is often overlooked is America’s British Culture.

His best selling book, selling more copies than all his other books combined, was his novel Old House of Fear. It’s a lot of fun, perfect for Kirktober.

You’re also a big fan of Wendell Berry. If I’m honest, I’ve struggled with Berry and the whole agrarian vision. What message does Berry offer the world needs most of all—and, echoes of the above, how do you sell it?

Russell Kirk was an admirer of Berry, and favorably reviewed Berry’s early major book The Unsettling of America. Like Kirk, who called himself a “Northern Agrarian,” Berry rejects the abstract in favor of the immediate and concrete, the local: hearth and home. Don’t get hung up on Berry as a farmer. He isn’t making a call for everyone to farm.

Berry stands in the traditional Jeffersonian stream that seeks a thriving independence for the yeoman farmer and the shopkeeper alike. He’s advocating for community rather than living our lives in detached atomization, which our virtual world has only exacerbated.

For Berry, read some of his Sabbath poems and his fiction as entry points. The novel Jayber Crow is probably his masterpiece and I recommend it to everyone. A lot of the readers here would probably appreciate his book Standing by Words.

“I can’t think of anything more enjoyable than to spend a rainy day in a large new-to-me used bookstore with nowhere else to be.”

—Alan Cornett

You have a well documented love for barrister bookcases. Tell us about that and your love for book culture more broadly.

A local acquaintance called me a “barrister bookcase enthusiast” recently, which I thought was funny. When I was an undergraduate I started frequenting used bookstores, especially Black Swan Books in Lexington. There were multiple barristers there, and it was probably the first time I’d ever seen one.

A few years later after grad school I worked at Black Swan off and on, and my wife and I would also sometimes house sit for the owner, Michael. He had old barristers throughout his home. I remember helping Michael move some barristers he had purchased and him giving me advice on how much to pay for them.

My first barrister was purchased piece by piece from Levenger back when they sold them. Although new, they were built to the old classic barrister standards. I ended up with a five-stack, then they ceased production. My first vintage purchase was a three-stack that was living a purgatorial existence housing a Beanie Baby collection. In the past few years I’ve purchased . . . more.

The standard was made by Globe-Wernicke, but others like Macey made them as well. Keep your eyes open and you can find deals. Only buy true stackable barristers, not modern connected pale copies.

I’ve had a thirty-plus years affinity for all things bookish, whether it’s typography, paper making, fine editions, letterpress, first editions—I’m always drawn like a moth to flame. I can’t think of anything more enjoyable than to spend a rainy day in a large new-to-me used bookstore with nowhere else to be.

One thing I’ve come to appreciate about your presence online is your way of turning the odd interest or touchpoint into a larger happening. This comes out in the Italian tours sponsored by your podcast, Cultural Debris. It’s also part of what drives your attempt to translate Iceland’s Christmas Jólabókaflóðið tradition to Twitter in an American context. What is that, and how does it work?

Do I have odd interests? (Likely guilty!) I have to credit my friend—and now partner—Tom Ruby for the idea of Cultural Debris Excursions. But the idea was a good fit for the podcast and for me personally. We’re traveling to Spain and Italy in 2024 if anyone wants to go. We’d love to have you.

Jólabókaflóðið goes back to my love of books, and it seemed like a great way to connect my Twitter mutuals who might not know one another around books. The past several years I’ve coordinated a Twitter based book exchange with fifteen to twenty people who respond. Each person sends a book to another person I assign and then they receive a book from someone else. I usually end up sending books to several people who I think may need something. I pick up good books in thrift stores all along just for giving away.

I suppose I have a natural tendency to want to pull people together like that. I do have a vision of a large Kirk Night banquet, for example. Small dinners have already happened, we’ll eventually go big! I also want to start a local pub night and have thought about doing a black-tie winter dinner as an excuse to wear my dinner jacket.

What’s behind the name Cultural Debris?

Cultural Debris is a term I shamelessly lifted from Russell Kirk. He wrote an early short essay with that name and I’ve always liked it. I think he liked it, too, because he included it in the Viking Portable Conservative Reader that he edited.

I’ve always enjoyed searching through used bookstores (see above), antique shops, and thrift stores. I’m looking for treasure but you never know what it will be. The last thing you’ll ever find is what you’re actually looking for, but that’s the fun. I love old things—especially neglected things—and seeing their real value and giving them new life.

“I love old things—especially neglected things—and seeing their real value and giving them new life.”

—Alan Cornett

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

I’ll start with St. John Henry Newman who is my patron saint and also is featured prominently in Dr. Kirk’s The Conservative Mind. G.K. Chesterton would bring a great deal of joviality to the evening. For my third choice I’m going with Jane Austen, who I suspect would be a great conversationalist. I would mostly be quiet in the presence of such giants, but I do hope there would be a lot of laughter. I’m going to cheat and offer an alternate dinner of three with Flannery O’Connor, Pope Benedict XVI, and Shakespeare.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post:

I never heard of Dr. Kirk before. Now I have another author to read.

My younger self knew even less than I do now, but some tidbits I was smart enough to preserve included a few odd copies of The University Bookman my old man had hanging around. Thanks for this…& Happy Kirktober!