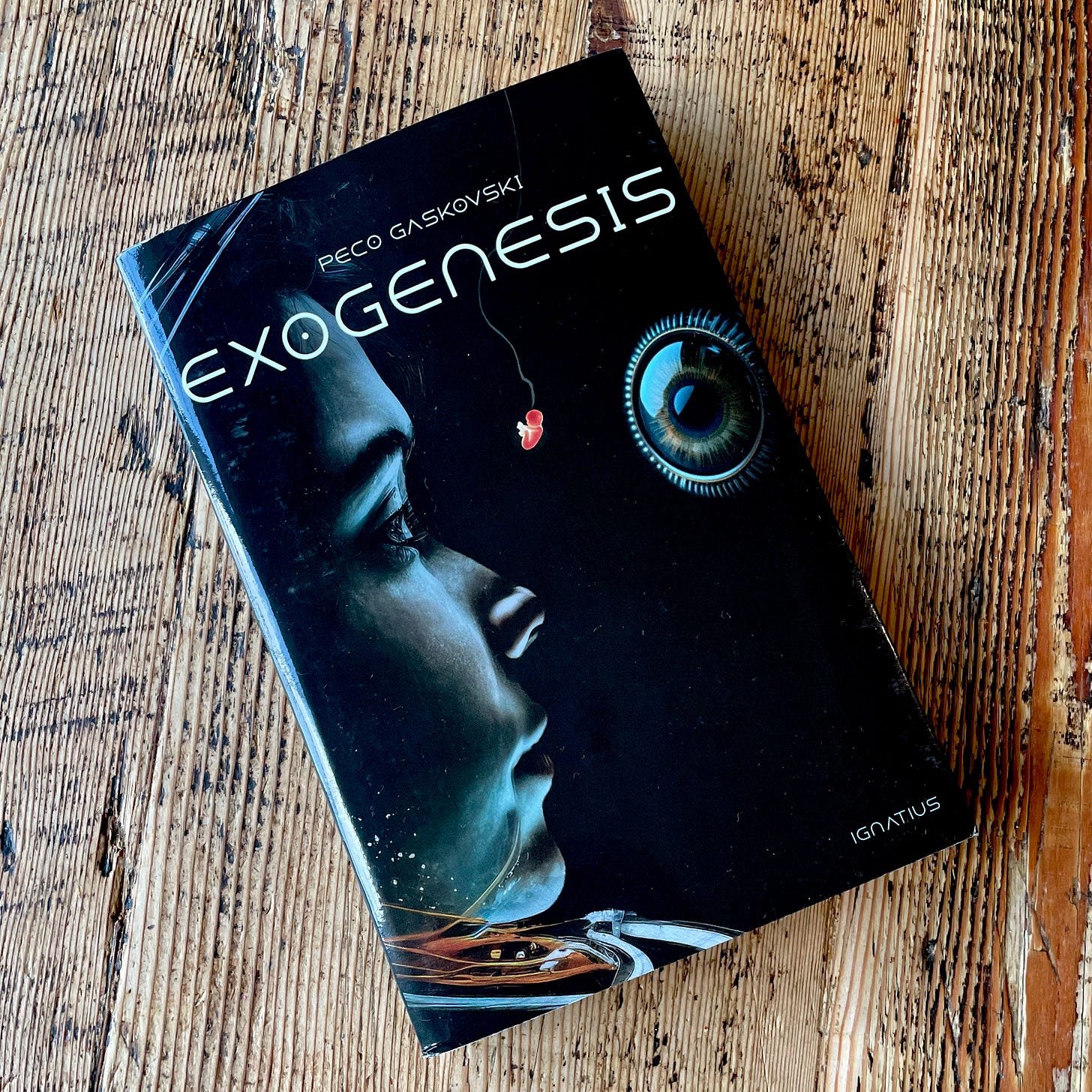

‘Who We Are Depends on Who’s Watching Us’

A Provocative Question: Reviewing Peco Gaskovski’s Sci-Fi Thriller, ‘Exogenesis’

How would your life unfold living under constant surveillance? Not openly sinister scrutiny. No, I’m talking about benevolent oversight, where social infractions and violations cost you points but where prosocial behavior boosted your account and elevated your class along with your score. The Eyes are watching.

Ubiquitous surveillance and social scoring are only two of the developments Peco Gaskovski imagines in his sci-fi thriller, Exogenesis. There’s another in the title. A few hundred years from today the citizens of Lantua City, a thousand-mile metropolis stretching from the eastern seaboard to Chicago, no longer have children the usual way. Instead, couples’ sperm and eggs are fertilized and up to three hundred embryos are gestated in “biopouches.” The prospects of each are then subject to sophisticated analysis, and the lucky couple selects their child based on predetermined traits and potentialities.

The genetic lottery of traditional “body birthing” is deemed backward and regressive, and couples are largely limited to one child. The quota serves as a response to an earlier demographic crisis, one implicated in the larger catastrophe from which Lantuan society rose in reaction.

Not everyone goes along with this regime. Gaian feminists protest the birthing policy. Like the Mother Earthers who intentionally live in the Territories, beyond Lantuan borders, the Gaians insist on the moral superiority of natural childbirth. Their fellow Lantuans regard them as extremists. The most extreme, however, are large communities of self-exiled Benedites, religious refuseniks in the Territories.

Lantuans rely on the Benedites to source their nonsynthetic food supply and to serve as buffer between them and the Zhang Chinese colonies further north. But like any strategic asset, the Benedites must be managed. Lantua actively limits Benedite fertility through a mass sterilization program enforced by the PMD—Population Management Department. Without intervention, Benedite populations would swamp their Lantuan neighbors. Only one child per family is allowed breeding status; the rest are “protocoled,” rendered infertile.

Counselor Maelin Kivela, who maintains a PMD team in the Territories, runs the program, while working to lower Benedite numbers by other means as well. Kivela convinces as many Benedites as possible to quit their communities, to defect, offering them inducements to join Lantuan society. Many take her up on the offer, though not all. Some violently resist.

Benedite insurgents, having acquired technology to scatter the PMD team’s protective drones, attack Kivela’s convoy after one fateful protocoling excursion. She survives unharmed, but several of her men are killed before reinforcements rescue the group and take one singularly important prisoner, Patrik Witsun.

Kivela’s life fractures upon return. She and her partner are mid-process choosing a child, one of 296 promising embryos vying for selection. They won’t raise the child on their own. Lantuan parents aren’t actually parents, only guardians; their children are farmed out to caregivers who do most of the raising. Still, it feels like an impossible choice for Kivela. Dogged by a recurring dream, she possesses a secret she must suppress. No luck, thanks to an unwelcome visitor from Kivela’s past and the captive Witsun, who Kivela is enlisted to interrogate.

Insurgent threats against Kivela mount, and she is subject to increased protection in the form of a personal police drone—an Eye—that follows her everywhere. The suffocating surveillance prompts one of the novel’s many trenchant observations about humanity: “The goal of the system, as everybody knew, was to track or restrict not ordinary human behavior but only dangerous or prohibited behavior.” But what counts as dangerous or prohibited in a society structured solely for the security of the state, that regulates everything from how children are born to the beliefs in your head?

“Who we are,” says a pivotal figure in Kivela’s story,

depends on who is watching us. . . . It used to be, long ago, that a child was watched and therefore known by his mother, his father, by the gods or the spirits that oversaw life, by all those who mattered to the child, mattered because the child’s purpose and existence depended on them. Now we give our children to caregivers. . . . The caregivers do not watch over our children with the sacrificial commitment of a mother or father, or of a god. So who watches over them? Who watches over all of us? Who watches with lifelong vigilance and concern for who we are and what we do, every moment of the day? The Eyes. The Eyes are everywhere, judging every word. Every action. . . . The Eyes watch and reward and punish. And the worst of it, Maelin, is this: the Eyes on the outside become the eyes on the inside, and the eyes on the inside become our true judges. Our moral conscience. The ones we seek to please. Our God.

Human freedom depends on choice, but Lantuan society is engineered to determine some choices and bar others. Kivela supports it all, a satisfied citizen racking up her social points and moving up the ladder—that is, until her recurring dream and the identity of the prisoner Witsun merge in a crisis that forces Kivela to make choices disallowed by her city, including one so momentous it shakes the foundation of the entire civilization.

Who’s watching? For whom are we acting, performing, choosing, deciding, loving, hating? Exogenesis places that question centuries into the future. It also prompts us to answer today.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related fiction:

Fascinating. At first I expected the title quote to refer to moral behavior, as in we change how we behave based on who is around. I imagine that’s not wholly incorrect, but the fuller quote gives a different perspective more about identity. We are shaped by those who see us, know us, and care about us. And if there is no one in that category... Much to ponder there, it seems.

Sounds interesting, I will certainly add it to my to-read list!