Under the Influence: Why You Want What You Want

The Real Power of Suggestion. Reviewing ‘Wanting’ by Luke Burgis

Why do we want what we want? We think we want things for their inherent value. But value is socially constructed to one degree or another. So the real answer is that we want what we want because other people say we should.

You can’t make it through the day without encountering examples: influencer culture, driveway jealousy, lifestyle publications, Facebook stalking, humblebragging, “I’ll have what she’s having.” Not to mention: adverts, product placement, trade shows, and all the other projectors of desirability we encounter on the regular.

Ever since the first person knapped a spearpoint and showed it to his friend, we’ve been wanting what our neighbors suggest, either directly or indirectly.

The Dynamics of Desire

We live amid communities of desire. The values we prize, the jobs we covet, the relationships we pursue, the competitions we join, the stuff we buy, the junk we discard are all influenced by the circles in which we move. No escaping it. It’s how we, as social animals, are wired.

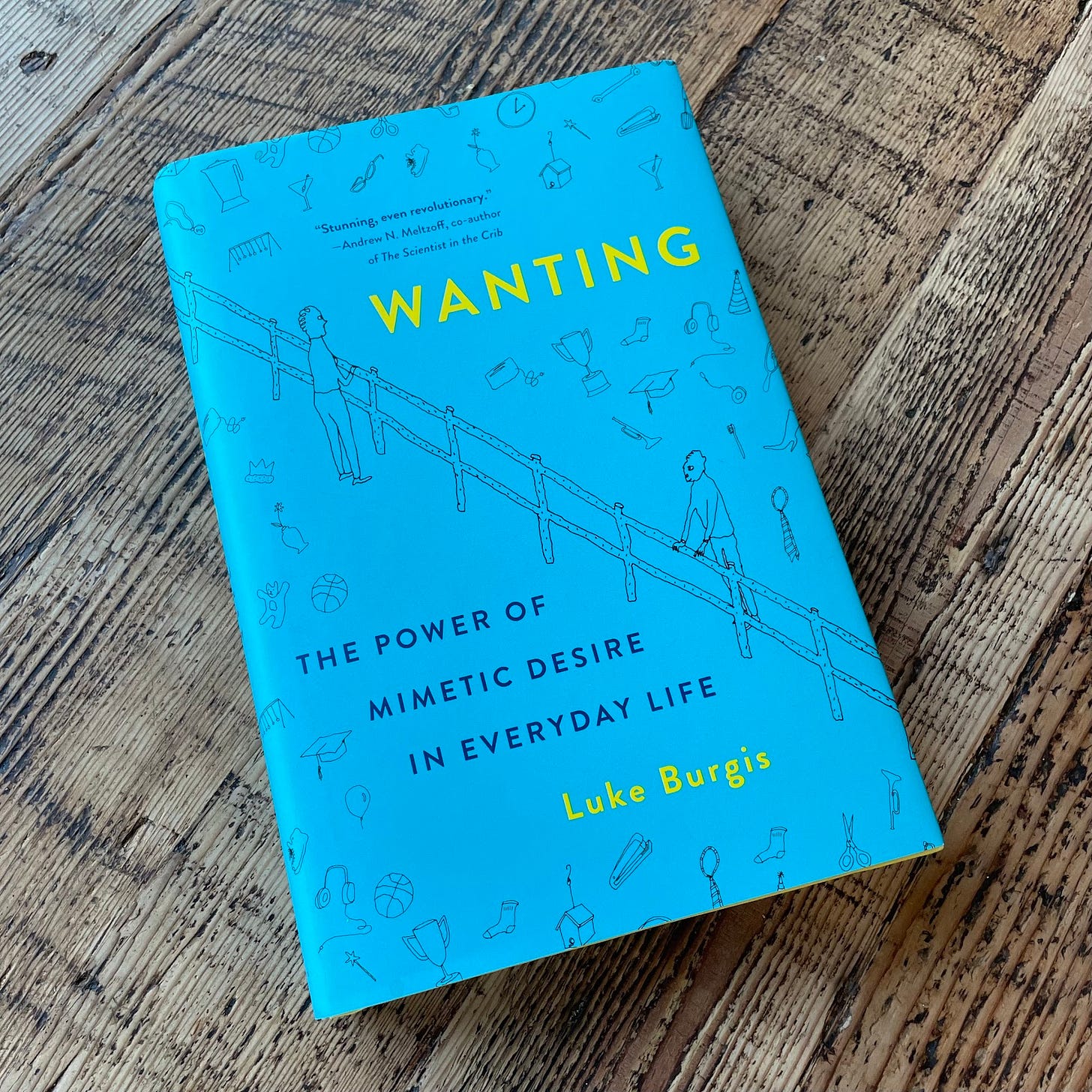

In his book Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, entrepreneur and academic Luke Burgis explores this subject from multiple angles along with the many ramifications for daily life.

Mimetic comes from the same Greek source as mimic. When it comes to desire, we’re all copycats. People, says Burgis, “believe that there is a straight line between them and the things they want. That’s a lie. The truth is that the line is always curved.” Our desires are mediated by models.

Failing to recognize the mediation, we also fail to recognize how those models influence our desires. And the results aren’t always pretty. “There are always models of desire,” says Burgis. “If you don’t know yours, they are probably wreaking havoc in your life.”

I can think of several examples in my own experience, many of which are embarrassing enough I’ll just keep them to myself, thank you very much. But I see it crop up most wastefully in rivalries.

This goes back to a distinction Burgis makes between two basic kinds of models: celebrities and peers. Celebrities of all kinds project values and desires that we emulate. But they are on a different plane than the rest of us and so do not provoke rivalry.

Peers are different. Because we exist on the same plane as our peers, it’s easy for desires to turn competitive—even when the parties are totally unaware it’s happening, maybe especially then. But it’s important to recognize when it’s happening because, as Burgis says, “Mimetic rivalries don’t end well unless one of the two parties involved renounce the rivalry.”

Managing Mimesis

To help readers disengage from the push-pull of mimetic desire, Burgis recommends a raft of tactics. I’ll list a several here:

“Name your models.” Become aware of who and what is influencing you at work, home, online, church, wherever.

“Create boundaries with unhealthy models.” If certain people spur negative impulses, put some distance between you and them.

“Find sources of wisdom that withstand mimesis.” If it’s trendy, it’s bendy. Ground yourself in sturdier authorities that don’t shift with the moment.

“Establish and communicate a clear hierarchy of values.” Values aren’t equal. Ranking your values in importance will help you defend what you prize and deal with what you don’t.

“Put desires to the test.” Given all the difficult choices we face, imagine which decisions will give you peace not in the moment but later down the road.

“Look for the coexistence of opposites.” Note models that seem to successfully balance contradictory characteristics—e.g., humility and confidence. Instances like these disrupt our existing models and can point us to transcendent truths.

“Map out the systems of desire in your world.” Follow the incentives and look for patterns. There’s inertia to desire, and you’re more likely to escape the pull if you know where it leads.

“If you understand the systems of desire that color the choices of the people around you,” says Burgis of that last item, “you’re more likely to see emergent possibilities by daring to look in different directions.” The inertia of desire is key, according to Burgis because, as he says, “Desire is path-dependent.” One thing leads to another. “The choices we make today affect the things we’ll want tomorrow.”

Thick v. Thin Desires

Another helpful antimimetic strategy Burgis offers is to cultivate what he calls thick desires. Thin desires are unreflectively accepted, highly mimetic, and consequently fleeting. Thick desires, on the other hand, tend to be lasting because they come from a deeper place within us.

The tactics mentioned above can help us separate thick from thin. So can looking at our lives and examining what we find fulfilling. Fulfillment is an angled mirror that reveals motivation. It’s not unmediated desire, but highlights desire truer to who we are than what tumbles down our Insta feed after a mindless scroll.

And it’s powerful. Thick desire is the foundation for lasting relationships, meaningful careers, even societal contribution. After all, as Burgis says, “The greatest developments in history are the result of someone wanting something that did not yet exist—and helping others to want more than they thought was wantable.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

This is helpful. Thank you.

Thanks for your review. I think it might be important in a review of this book, to say something about how it is based on the work of René Girard.