Bookish Diversions: Lifetime Reader

6 Decades of Books, Nobody’s Reading—Even Though They Want to, Do Men Read Novels? More

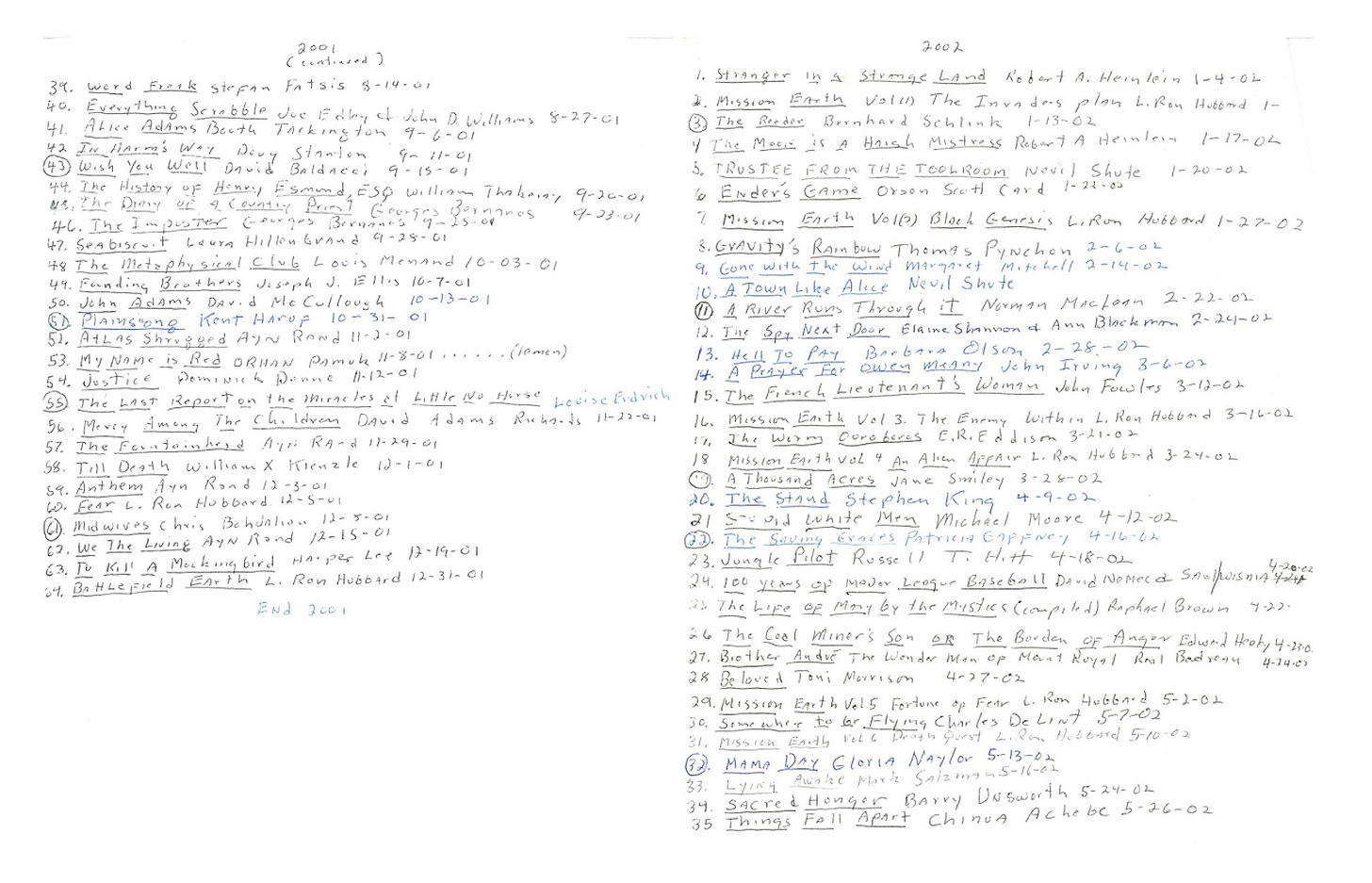

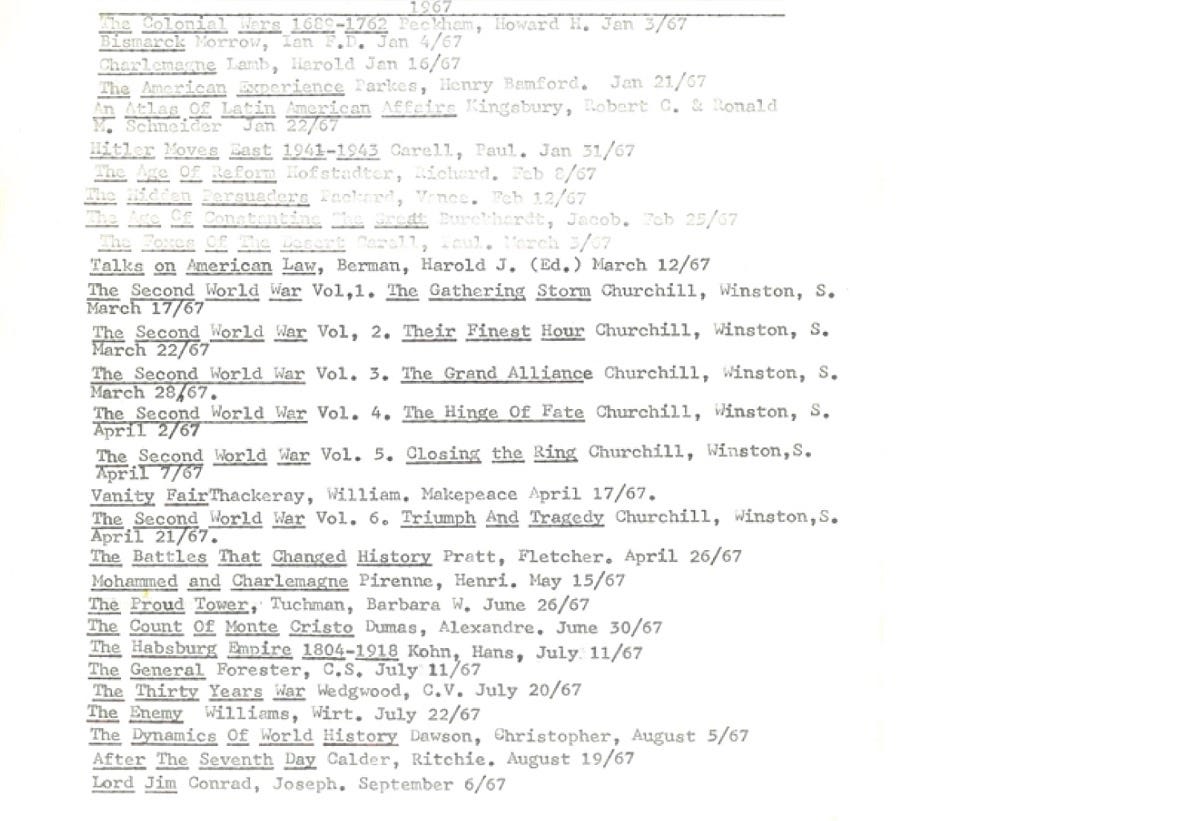

¶ A lifetime of reading. When Dan Pelzer passed away earlier this month in Columbus, Ohio, the 92-year-old left behind a treasure: a 109-page log listing thousands of books he’d read since 1962.

That was the year he found himself in Nepal as a Peace Corps volunteer. During his off hours he worked his way stacks of paperbacks collected in a small library there. Pelzer kept up the habit when he returned home.

Money was tight. “Financially, I was two steps ahead of the sheriff in those days,” he said. So he took a second job and borrowed books from the Columbus Metropolitan Library. Pelzer kept his library card current and checked out most of the books on the list.

His family thought about sharing his list at the funeral, but it was too long to print. Instead, they posted scans of the pages online at What Dan Read. And bless them for it, because now we can all read what Pelzer was up to for the last 60 years. It’s a fascinating artifact of a life lived with books; you can spend hours just browsing through the years.

In Nepal Pelzer read Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis, Owen Wister’s The Virginian, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Moby Dick, and The Hound of the Baskervilles. But he also read Rats, Lice and History by Hans Zinsser, The Wonder That Was India by A.L. Basham, Nicholas Hotton III’s Dinosaurs, and The Inquisition of the Middle Ages by Henry Charles Lea. He read James Fenimore Cooper, the Brontë sisters, J.D. Salinger, Gogol and Turgenev, Graham Greene, and lots of C.S. Forester—not to mention C.S. Lewis, Milton Friedman, Tocqueville, the Dali Lama, and H.G. Wells.

It would be easy to assume he couldn’t be choosy, given what was available in his little Nepalese library. But his interests appear just as diverse and wide-ranging once he landed back in the states. He found James Joyces’s Ulysses “pure torture,” but he wasn’t afraid of anything—tackling classics, Greek tragedies, modern fiction, history, sociology, theology, philosophy, biblical studies, criminal justice, and more. He supposedly finished every book he started.

Most of the entries include the date he finished each book. In 1967, for instance, he read Winston Churchill’s complete Second World War series, interrupted by Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, along with biographies of Bismarck and Charlemagne, Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders, The Count of Monte Cristo, a bit more C.S. Forester, Lord Jim by Joseph Conrad, and Ritchie Calder’s After the Seventh Day: The World Man Created.

Some years he clocked more than 80 books, but in a few he struggled to make much progress at all. What was going on in 1973? He read just seven, including A Canticle for Leibowitz. And in 1974 he read just two, among which was All the President’s Men by Woodward and Bernstein. By 1976 he was ramping up again. He read 28 volumes that year, including four by James Michener—three back to back—and two by C.S. Lewis.

Pelzer’s Catholic faith comes through, but so does his interest in other traditions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and other world religions. St. Paul and His Letters sits right next to The Way of Zen by Alan Watts.

There’s very little detail in the log—just titles, authors, and dates. But the cumulative effect is entrancing. In total it contains 3,599 books, though his family pegs the complete number at over 5,000. The last book he read? David Copperfield.

One of Pelzer’s tricks for reading? Make the most of the time you have. When money was tight, Pelzer found extra work as a security guard. In between taking care of his responsibilities, he’d pull out a book; after clearing all the patrons from the bar at the local Marriott, for instance, he’d dip into James Michener. “All of the sudden,” he recalled, “I would be in the South Pacific.”

Memory eternal.

And the rest of us? We’re a mess.

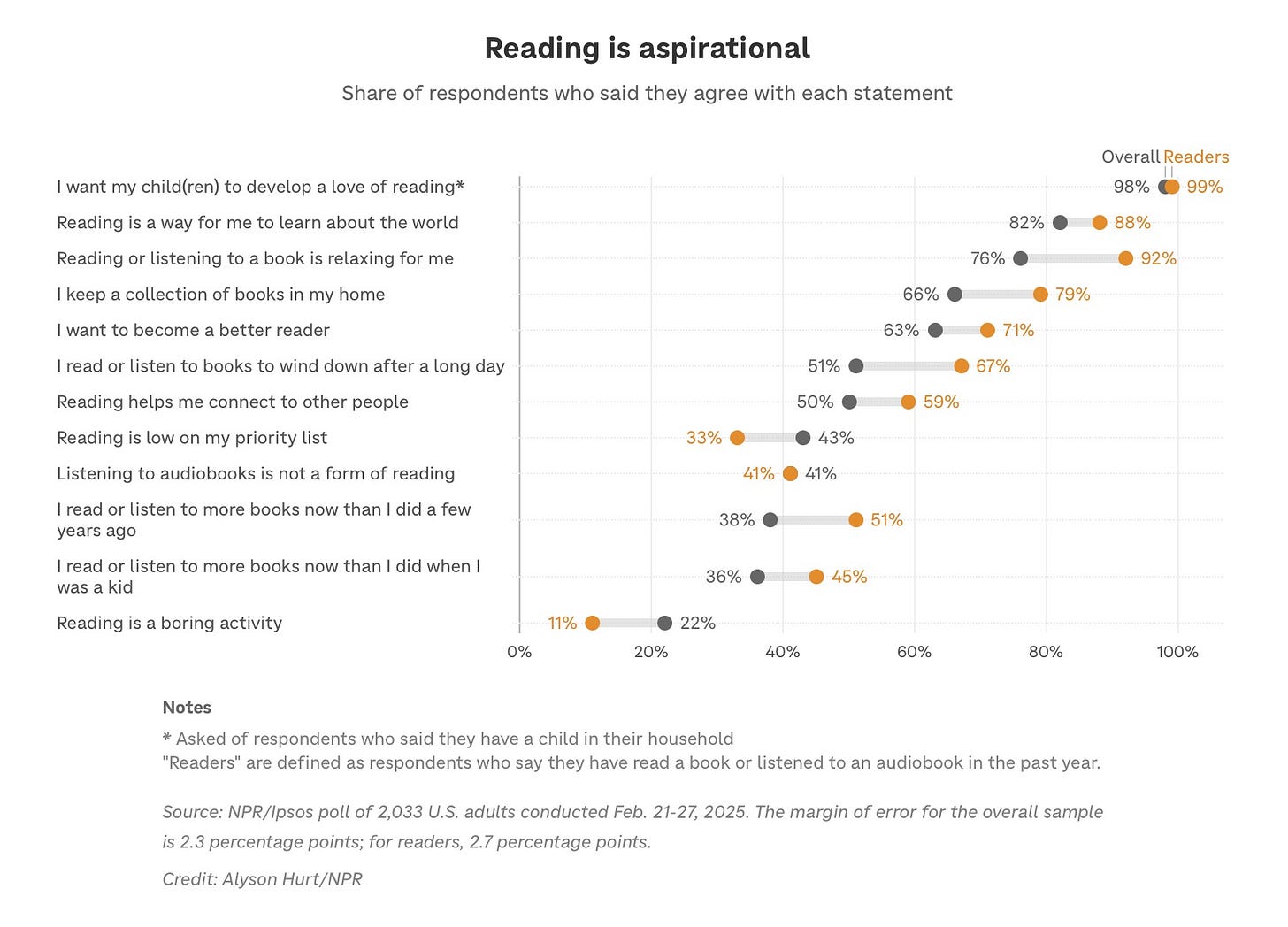

¶ Everyone wants to read, but nobody does. Well, not nobody. But we’ve all seen the statistics, and they’re abysmal. Interestingly, however, we’re sending mixed signals. An overwhelming majority of Americans, according to an NPR/Ipsos survey, say

they want their kids to love reading (98%);

spending time in a book is a good way to learn about the world (82%);

they themselves find reading relaxing (76%); and

they want to become better readers (63%).

And yet! “Despite holding these positive opinions about reading,” say pollsters, “43% of Americans agree that reading is low on their priorities list.” Whatever we make of all the aspirational talk, barely half of Americans (51%) reported reading a book in the last month. This is the Augustinian Paradox applied to reading: “Lord, give me bibliophilia, but not yet!”

¶ What’s to blame? Why aren’t people reading? It would be easy to blame phones, video games, or television. But the NPR/Ipsos survey wasn’t that cut and dried. “Respondents who classify themselves as readers are also more likely than non-readers to consume other forms of media,” writes NPR’s Alyson Hurt.

So it’s not necessarily a direct competition between, say, reading and scrolling on your phone. When asked about the “reasons you don’t read more,” “other life activities” was the most common answer, which could mean anything from doing chores to sleeping to hanging out with friends. . . . When asked what they’d do with one extra hour of leisure time, the top of the list is spending time with family [that’s a plus, right?—JJM]. Below that is a tied race between watching TV, reading and exercising.

But, of course, it does come down to available hours, and time-use data shows that most of us tend to default to television when leisure time is available—regardless of what we might tell a pollster.

In 2016, the typical American spent more than twelve times as long watching TV as reading. Between 2003 and 2016 the time Americans devoted to leisure reading slipped from roughly 22 minutes a day to just 17 minutes, while TV rose from 3.28 hours to 3.45 hours per day. That data is a bit old, but I can’t imagine the trends have edged away from television and toward books in the meantime.

Anecdotally, most of the people I know talk about the TV shows they’re watching, not the books they reading. And I don’t fault them. I’ve seen some of those shows and they’re fantastic. Even if 76 percent of us find reading relaxing, we might still opt for Netflix or Hulu because it’s also relaxing and the quality of TV is actually quite good these days. Throw the advanced state of gaming into the mix, and Dostoevsky has an uphill climb.

¶ But we do know men stopped reading, right? Despite the bright, blazing beacon of Dan Pelzer, men do tend to read less than women. Out of the 51 percent of Americans who said they read a book in the last month, women did so at a higher rate than men (56% vs. 45%), according to NPR/Ipsos.

And now we plunge into a perennial handwringing exercise about the loss of male readers, especially when it comes to fiction. A typically cited stat claims that women account for 80 percent of the fiction market, men just 20 percent. Writing for Vox, Constance Grady shows this is likely bunk.

Still, more legitimate numbers are somewhat discouraging. As of 2022, fiction readers comprise just 38 percent of adults, according to the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts with 47 percent of women reading novels and short stories but only 28 percent of men. Worryingly, these numbers represent a downward trend for both women and men.

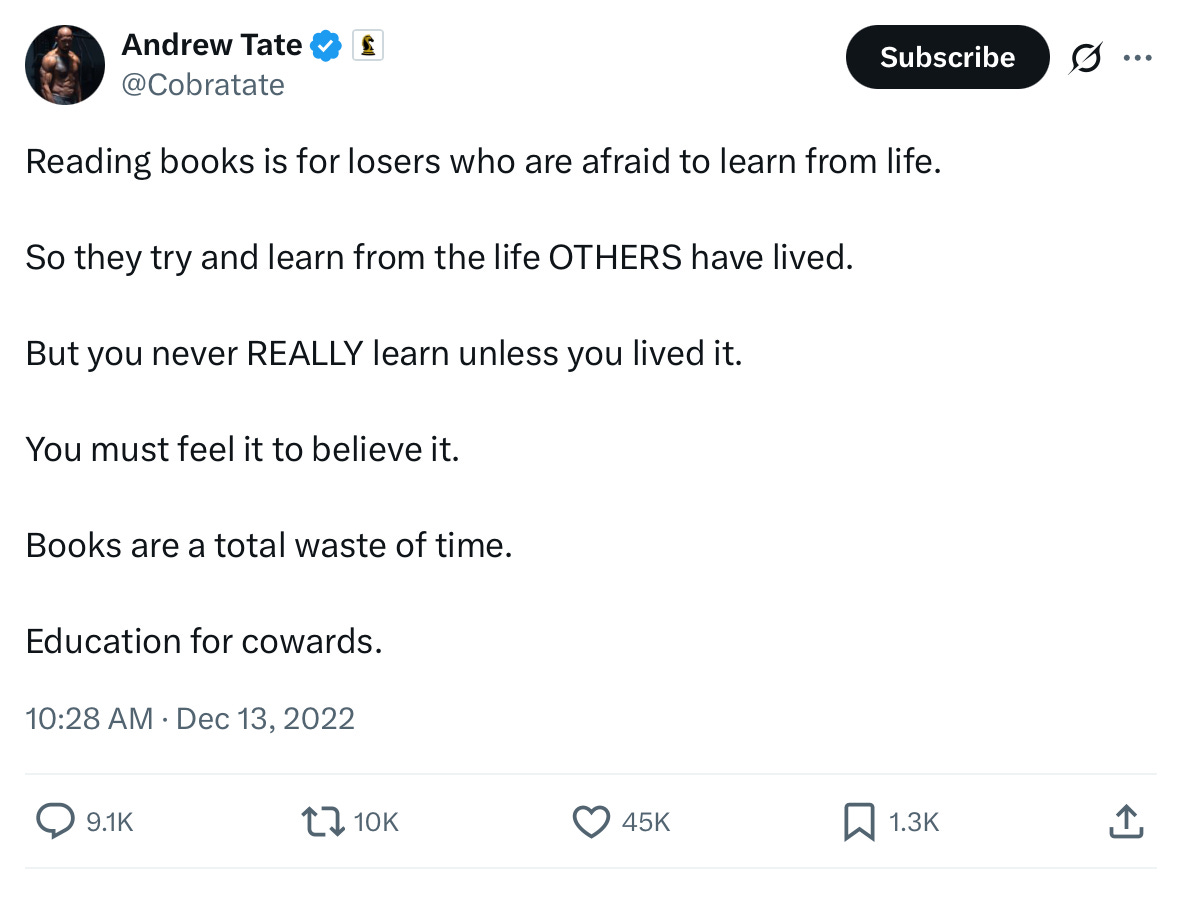

Speaking for the XY side of our chromosomal divide, manfluencers like Andy Tate aren’t doing our sex any favors.

Isn’t he just precious? And then, of course, there’s the equally adorable Sam Bankman-Fried. “I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading,” said SBF, not long before accepting holiday accommodations at Stony Lonesome, “but I actually do believe something pretty close to that.” Obviously worked for him!

There’s plenty of thoughtful writing on the question. I appreciate Ed Cummings’ take, as well as that of Johanna Thomas-Corr. And then there’s the always-optimistic Henry Oliver:

There is still plenty of good writing, plenty of literary energy, but it is not always in the same places it used to be, and the literary establishment isn’t always well aligned to its audience. We are living through a significant disruption. Instead of responding with despair, we need to adapt. This is fully achievable.

¶ The thrill of reading. Dan Pelzer knew: Reading is amazing, astonishing! Open a book and you jump into the mind of another human.

Joan Didion, God love her, got this roughly backwards. She equated writing with a form of violence. “It’s hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it,” she told the Paris Review in 1971, “trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way.”

Novelist Jeremy Gordon takes the opposite view, that reading represents a form of autonomy. He’s in control, not the other way around. “Literature,” he says,

allows me to occupy a place that is totally for myself, and unaccountable to other people’s expectations. The author Percival Everett is fond of noting that he considers reading to be a subversive act. “No one can control what minds do when reading; it is entirely private,” he once said. This, to me, is the best argument for why a man should read, and why he should seek new mental frontiers beyond the accumulation of information. Reality is linear, but reading skips backwards and forward, allowing me to consider the world from a removed vantage point. Instead of feeling squeezed by my earthly existence and my own bodily limits, I leap into other minds and perspectives. . . . I am reminded that everyone is unexceptional and everyone is exceptional. Facts can sometimes tell us this about humanity, but fiction does this best of all.

Reading is not a passive experience in which the writer hijacks the mind of the reader. It’s an adventure the reader determines, whatever path the author has charted. If we give any credence to Didion’s sentiment, we can only go halfway—the author may try to assert his or her vision, but the reader is the one with the final say. Every page is participatory, a high-stakes negotiation, potentially a thrill ride, “unaccountable to other people’s expectations.” What man wouldn’t like that?

¶ Turning the tide. Some of our problem goes back to the very disparity highlighted by the NPR/Ipsos survey. We feel as though reading is good for us, but we don’t bother actually doing it. Why? In part, we’re selling the wrong thing! Reading isn’t fundamentally about learning or relaxing or developing empathy or whatever else. It’s about having an experience unlike any other, and one easily optimized by the reader for the reader by simply following their whims.

“My feeling is that less eat-your-greens hectoring and more playfulness in literature would do us all a lot of good,” says Thomas-Corr. “Instead of making contemporary fiction yet another arena for virtue-signaling, sanctimony and bad-faith assumptions about the contents of each others’ souls, let’s make room for genuine mischief and mess, experimentation and individuality.” Amen. And turning the tide comes down to simply sharing what we love and why we love it, as so many wonderful writers here on Substack do on a daily basis.

“Each of us has the power to show that reading does matter,” says Meghan Cox Gurdon.

We can do it by reading—and being seen reading—with dedication, bravado and a bit of countercultural aggression. Be the person on the train who pulls out a paperback rather than a phone. Be the parent in the pediatrician’s waiting room who reads a story rather than letting your child zone out on a tablet. Be the spouse who chooses a novel after dinner over the television. Be the teacher who transfixes the class with a live reading rather than a canned video. Revive the old social norms by setting them yourself.

If you need any inspiration, just do it for Dan.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend. Or an enemy. I don’t discriminate!

And! More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

Man. That quote from Andrew Tate is ridiculous! I really do worry about the modern loss of literacy. It is one of my greatest concerns for the future of humanity. If you don't read, it's hard to gain critical thinking skills and baseline knowledge. You will be tossed back and forth by the waves of popular opinion, viral videos and memes, and whatever most people seem to be doing. And sadly, at different periods of history, "whatever most people seem to be doing" may include acts of violence, fear mongering, or just being generally ignorant. I don't mean to be a doom spreader, but it really is easy to not be an idiot—just read more books—and most people seem unwilling to do that.

It's ironic that we live in an era when practically every great classic is available for free as an eBook, yet reading is down.

I think our constant use of smartphones has messed up our ability to focus for lengthy amounts of time. Every summer when the school year ends, I have to retrain myself to sit and read without feeling a need to check my email, newsfeeds, etc.