Let Us Now Praise Humble Bookmarks

Bookish Diversions: Accessing Ideas, St. Augustine’s Placeholder, Personal Favorites, Library Leftovers, More

¶ Finding ideas. In his book Stubborn Attachments, economist Tyler Cowen mentions the contribution of ideas to increasing returns. “Once an idea has been generated,” he says, “it can be used many times by many different people at very low marginal cost. The first idea spreads, begets subsequent ideas, and so growth increases.”

But how do you access those ideas? My citing Cowen indirectly offers one answer. I read Stubborn Attachments five years ago and remembered this idea about ideas. Talk about repurposing at low marginal cost: I bookmarked the page in 2018 and found the quote just now in 2023. It took me seven seconds. People have relied on similar maneuvers for ages.

¶ St. Augustine’s placeholder. In a pivotal scene of his Confessions, Augustine retreats to a garden. Distraught, he clutches a book as he goes. Thinking to comfort him, Augustine’s friend Alypius follows him outdoors. The pair find a place to sit far from the house they’re sharing, but Augustine is inconsolable. Not wanting Alypius to see his tears, he wanders off once more, leaving his friend and his book on a bench. Finally collapsing in the shade of a nearby fig tree, Augustine sobs.

At that moment the singsong voice of a child wafts over the garden wall. “Take and read,” he hears. “Take and read.” He first assumes it’s the playful call and response of a game. But then he remembers his book! He takes it as a sign. Running back, he grabs the volume, opens it at random, and falls upon a passage that immediately salves his troubled spirit.

Many of us have had similar moments, and no doubt most of us dwell upon this portion of the story. But there’s more. When Augustine finishes, he says, “I placed my finger or some other marker in the book and closed it.” It’s a small but revealing detail. What Augustine first finds by chance he and his friend Alypius can now access by intention.

Cowen hosts a wonderful podcast, Conversations with Tyler, in which he often asks guests whether a person, place, thing, or idea is overrated or underrated. Bookmarks are decidedly underrated. Do we think about them at all? And yet our lives and literary pursuits would be much diminished without them.

¶ Bounty from the river. A book is a river of ideas, and no matter how attentive or engaged our reading we’ll never encounter the same river again. We require means to catch their insights and benefits before they dart past us like elusive trout. One method: writing in our books—an idea that unsettles some but which makes my life and work possible. I explain why here and invite any and all to adopt the practice even if you’re antsy about inking your pages.

Bookmarking is another method. These two work well together, but I want to focus on the simple practice of dropping an item between the leaves to hold your place. If a book is a river teeming with ideas, a bookmark is a net for catching them.

Almost anything will work: cover flaps, Post-It Notes, parking tickets, business cards (one of their few ongoing uses), 3x5 index cards, airplane boarding passes, electricity bills, torn strips of paper, lunch napkins, money, store receipts, quilted squares of bathroom tissue (you can admit it; you’re among friends), and of course the branded bookmarks little shops sometimes give out (about which more in a moment). If it’ll hold your place, it’s a candidate for inclusion; slip it inside and thank yourself later.

Like Google tracking backlinks, your trail of bookmarks can testify to how valuable you find the book. The more markers, the greater the reliance on, or interest in, the ideas bound inside. And that trail has reconstitutive power. Says novelist Eugene Vodolazkin,

Scholarly work . . . never moves in a straight line. . . . Any research is like the motion of a dog following a scent. The motion is chaotic (outwardly) and sometimes reminiscent of spinning in place, but it is the only possible path to a result.

Likewise, the bookmark trail is sometimes the only possible path to retrace your steps. Returning to the image of a river, your bookmarks can flag where the best fishing might be in the future.

¶ Show and tell. I’ve pulled two examples off my shelves to illustrate.

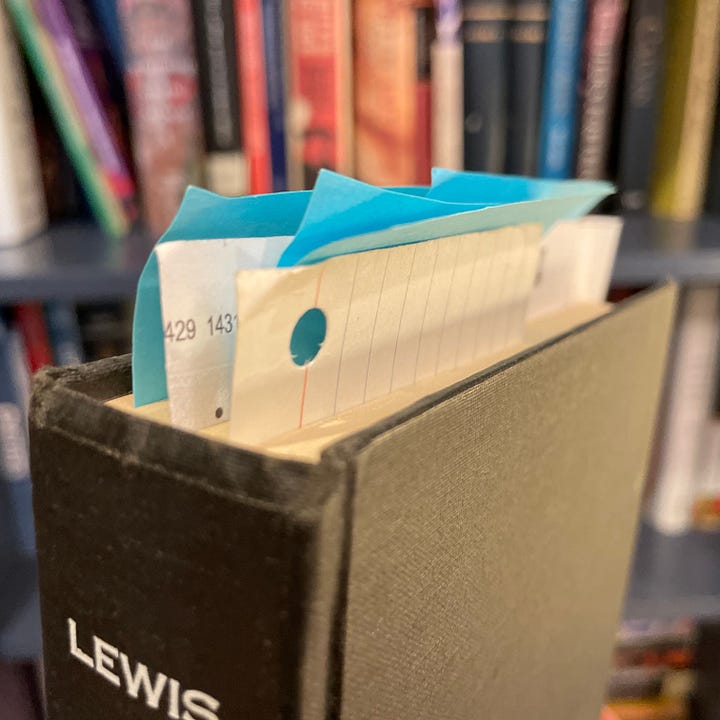

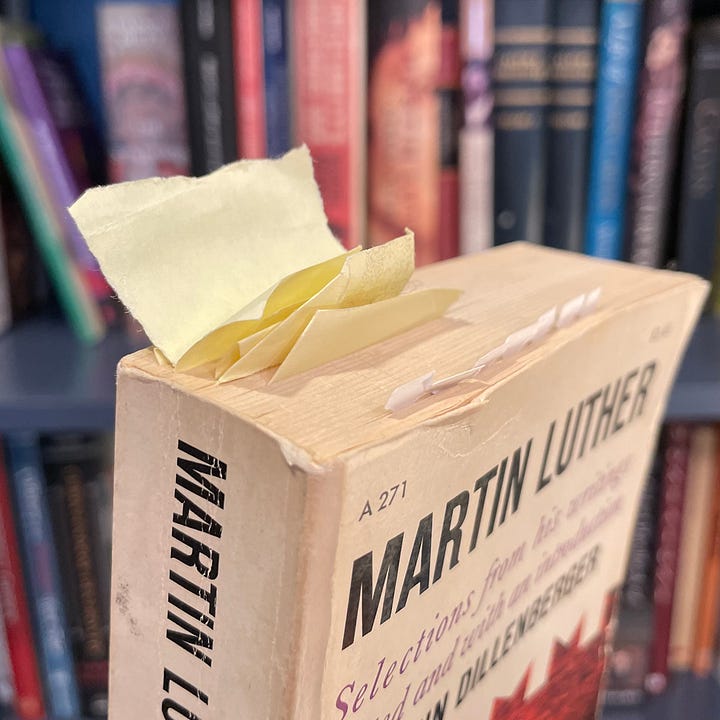

The first is a copy of C. S. Lewis’s God in the Dock. I count seven bookmarks, mostly blue Post-It Notes along with a page from a decade-old bill and hole-punched index card. Next is a little collection of Martin Luther’s writings. I’ve got eight passages marked there, all with bits of yellow Post-Its except one torn page from a memo pad.

My personal record for marked pages? Probably my copy of György Buzsáki‘s The Brain from Inside Out, the top of which bristled with fifty or sixty pink and blue Post-Its before I finally removed them.

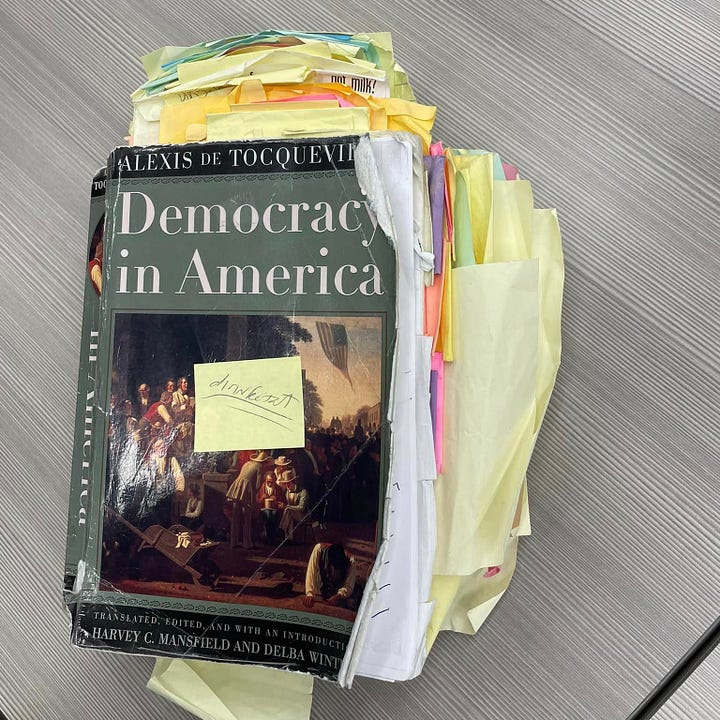

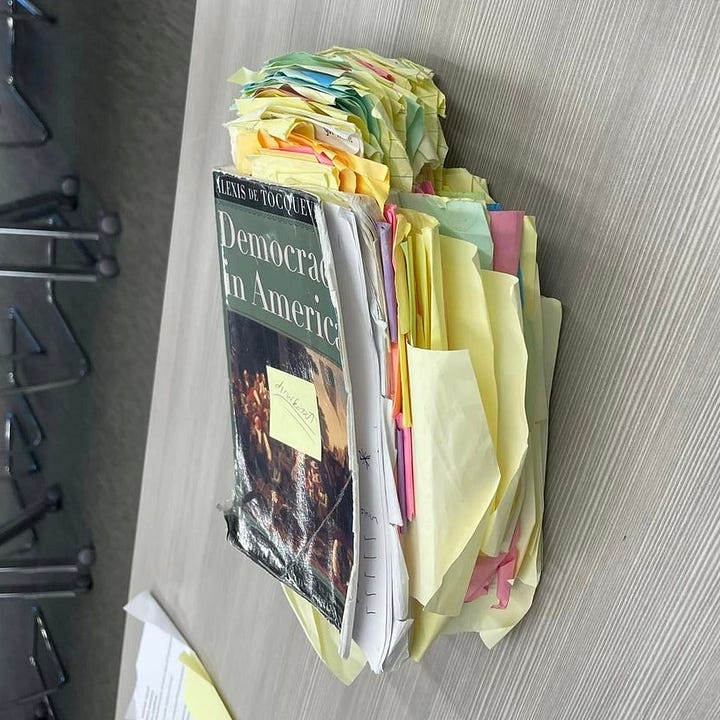

Nothing I’ve ever experienced, however, compares with Ken Masugi’s copy of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, photos of which were snapped by Steve Hayward, a friend who graciously allowed me to share this marvel. To my point that nearly anything will work for a bookmark, there are Post-Its of all sizes and colors; there’s at least one quire of Xerox paper scribbled with notes tucked in at the start; and if you look closely in the upper right of the book you’ll notice one slip of paper asking, “Got Milk?”

Safe to say Tocqueville matters to Masugi; his bookmarks reflect a near-religious engagement with the text.

¶ Personal favorites. Bookmarks with particular provenance can also from a trail of our actual travels. Retailers sometimes toss little slips of branded card stock in our book or bag as a bit of marketing, investing pennies in the present with the hope of more dollars in the future. A few pulled at random from books in my library take me from Medford, Oregon, to Nashville, Tennessee, and remind me of frequent sojourns to St. Louis, Missouri; Hudson, Ohio; and the beaches of the Florida Panhandle.

When I encounter one of these horcruxes, I recapture a fragment of my spent life. I recall particular books purchased at specific locations and all their attendant memories. I remember, thanks to the bookmark the clerk dropped in my bag, buying a copy of Christopher Hitchens’s No One Left to Lie To at Village Books one hot summer day. And the Sundog marker conjures a million memories, including a little biography of Isaac Newton purchased on my honeymoon almost fifteen years ago.

Naturally, we can get somewhat sentimental with such placeholders. The two pictured below remind my of my eldest daughter. One is a slip of paper on which she wrote a magical recipe for an imaginary potion when she was little. “Grind a tail of a Phonix [sic] and some unicorn spittle,” she directed to, I imagine, potentially dramatic ends.

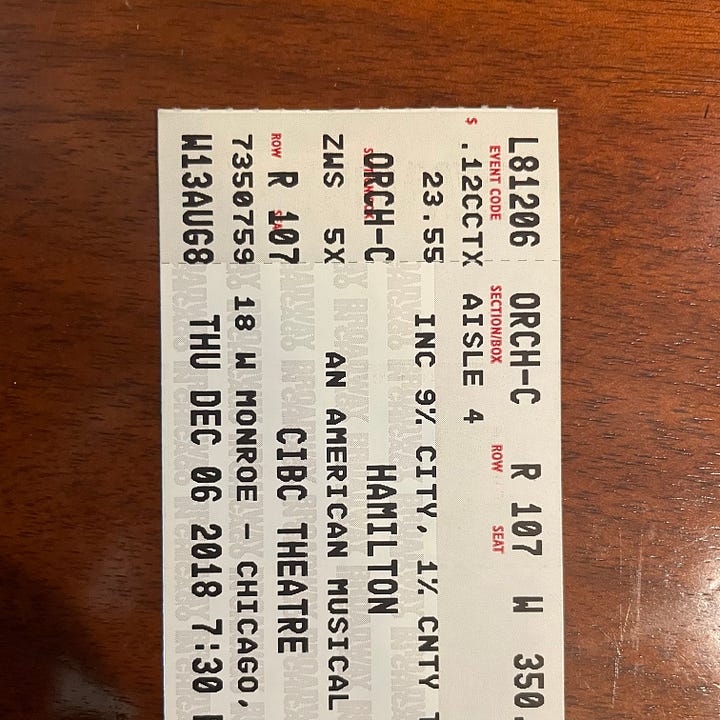

And then there’s a ticket to Hamilton, part of a birthday gift to the same daughter many years later. Upon returning home from the show, I tucked mine into a biography of Thomas Jefferson with an impish grin.

Another favorite I’ve mentioned (and pictured) elsewhere is a small photo of a hippopotamus marking the poem “The Hippopotamus” in an edition of T. S. Eliot’s poetry once owned by my late grandfather. The poem and the photo have shared each other’s company for decades and decades now.

¶ Things left behind. I cull my library on a regular basis. Before I part with a book, I usually rifle through it and remove any papers I’ve left inside, though I’m sure I’ve let some scraps slip by.1 I’m unsure why I clean up after myself because I always love acquiring books with bits of ephemera left by prior owners. Sometimes interesting notes, receipts, and—naturally—branded bookstore bookmarks hide inside.

Occasionally, the leftovers are more substantial.

Now and then I’ll tuck print review of a book I’m reading into the book itself. These are often articles I’ve read online and printed for later reference; where better to keep them than the book under scrutiny? Go back far enough and I would have torn those reviews from magazines. I recall, for instance, reading a review of Robert Dahl‘s How Democratic Is the American Constitution? while I was reading the book in 2001; I gave it a rip and placed it in the back of my copy. I did the same with a review of The Gospel of Judas in 2006.

Recently I repurchased a used copy of Christopher Hitchens’s 2000 essay collection, Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere. I misplaced my copy a few years back and wanted to thumb through it again. Tucked inside was a copy of the Economist’s 2001 joint review of the book and another essay collection, one by Hitchens’s friend, Martin Amis.

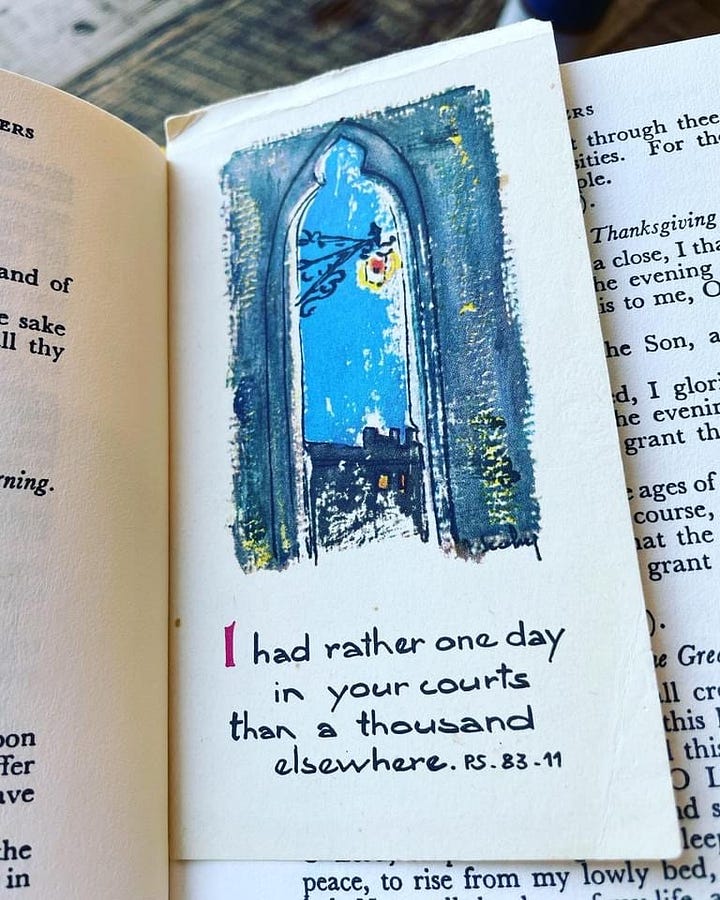

Displayed below are two sides of a bookmark from a used book I repurposed as a marker in my go-to prayer book, A Manual of Eastern Orthodox Prayers. The front features an image of a window from the perspective of someone looking outside on an evening sky, captioned with a popular verse from Psalm 83: “I had rather one day in your courts than thousand elsewhere.”

On the reverse, the prior owner had penciled in neat cursive letters a verse from the Gospel of Mark, Jesus’s warning about salt losing its flavor.

Items left behind can connect us in meaningful ways to their prior owners. When author Cath Crowley’s father died, grieving prevented her from spending time with his bequeathed books. “He and I had always communicated through books,” she said. “He would send me the book that he had just finished reading and I would read it and that’s how we would talk—we would have that conversation about the book.”

Eventually, however, she braved the feelings and cracked open some of his old volumes. “I found things written in the margin, tobacco from his pipe caught in the creases, and bits of my mum’s wool he’d used as bookmarks,” she said. “They became really precious things to me, and they did actually help me once the grief had moved past a particular point.”

Of course, not all items hold that kind of value.

¶ No excuse for that. The Oakland Public Library maintains a website featuring the items found in returned books. Along with the standard stuff—letters, photos, notes, and lists—patrons press all sorts of stuff between their pages, a crochet hook, sugar packet, Lady of Guadalupe card, beer coaster, and plenty more.

The publisher Tin House queried librarians about curiosities recovered from returned books. Among the more surprising items? Divorce papers and paychecks were interesting but nothing compared to the food. Novelist Clair Fuller reported on some the items mentioned, including: cooked shrimp, pickle slices, french fries, bologna, a Pop-Tart, a taco, even raw bacon. “I can’t even begin to think up a scenario for raw bacon,” she confessed.

¶ Final example. For the title of this piece I pinched a line from the Book of Sirach, chapter 44, verse 1: “Let us now praise famous men.” I was reading that bit not long ago and relocated the reference lickety-split with the golden ribbon provided by the publisher and bound at the top.

Returning to Cowen’s opening observation: “Once an idea has been generated, it can be used many times by many different people at very low marginal cost.” Indeed, especially if you bookmark it.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I usually don’t do this with notations. But here’s a wild tip for those anxious about writing in your books who would prefer to part with only pristine pages. Use Pilot’s erasable Frixion ink and you can make all your marginalia vanish with the application of a little heat. When I do feel the need to erase, I simply warm a spatula on my gas stove and touch the blade’s conductive surface the page. Voila! It never happened.

I recently visited a fine used book store in Norristown, PA. On a wall above the shelves they had assembled a collage of inserts found in the donated books (tickets, receipts, photographs, coupons, notes, ...). What a wonderful treasure! The name of the store: Recycle Read Repeat.

I was raised to treat books almost as holy. To write in them would have been sacrilege. The first time I did it, I almost expected to be struck by lightening. But I also delight in what readers have scribbled in the margins and tucked inside the pages when I find them. Sometimes I'm inclined to write a brief review or point out my favourite parts for the next reader. E-books may take up less space but they lack the potential for dialogue with the writer or other readers.