What the Humanities Can Offer Us (and AI, Too)

Hollis Robbins talks ChatGPT, African American Lit, Low-Ego Collaboration, and Her Best Productivity Hack

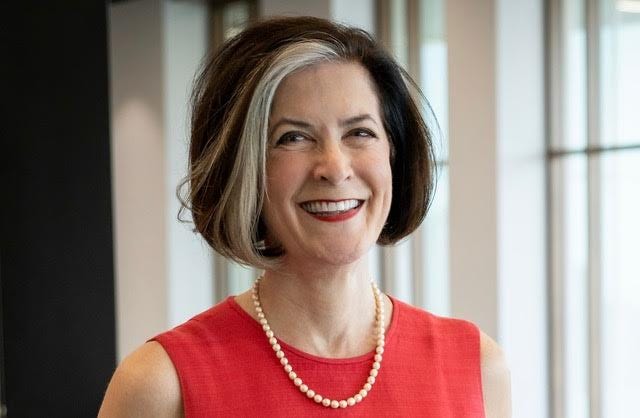

Award-winning educator Hollis Robbins is Dean of Humanities at the University of Utah. A scholar with deep expertise in nineteenth-century African American history and literature, she’s the co-editor of several important volumes, including Penguin’s Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers and Norton’s Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She’s also author of Forms of Contention, an exciting look at how Black writers adopted and adapted the humble sonnet to contend for their own personhood, dignity, freedom, even civil rights. I reviewed it here.

I first encountered Robbins through an episode of Conversations with Tyler and have enjoyed her work ever since, including her always-interesting Twitter feed. In this conversation, we talk about why people in the humanities might—contrary to expectations—be more accepting of AI tools such as ChatGPT than others, how she ended up studying Black history and literature, and her one best productivity hack.

Miller: You’ve been a vocal supporter of the humanities—their ongoing relevance, even their marketability. And you take that stand amid countless others mourning their demise. What’s the source of your optimism? What do you know that the naysayers don’t?

Robbins: I will be optimistic about the humanities until the day people stop reading books or going to the movies. People like stories! People like stories about human beings more than anything. Even science fiction is almost always about human beings encountering alien cultures.

We’re fascinated with ourselves. And as the technology advances, everything comes back to how new inventions are used by humans and affect humans. For example, scholars and writers in humanities disciplines have been grappling with concepts of artificial consciousness and mechanical humans for centuries, if not millennia.

New advances, such as ChatGPT, have suddenly made engaging with artificial voices a daily occurrence for millions. That’s what’s new for humanists—not the actual engagement with artificial voices. Chatting with fictional beings is familiar to us. And so we have jumped at the chance to try out these new technologies and to watch how non-humanists are awed, mystified, sometimes terrified.

You recently tweeted, “The best poetry has always been about the unpredictable next word,” which directly differentiates the way people and AI seem to work—or at least what produces delight for a reader and listener. Answering as a writer and educator, what are some ways of thinking about AI you find particularly helpful?

Humans have pondered artificial intelligences for millennia. Humanists begin with a recognition that the ethical and social implications of engaging with platforms like Bing or Bard or Claude or ChatGPT are both old and new.

One of the major issues I’m speaking out about now is whether chatbots should pretend to be human—should use the “I” to answer questions, as if it’s an actual voice. I tweeted a few months ago in response to concerns about having emotional reactions to AI that most professors have experience dealing with this in the classroom, teaching fiction.

Some people have strong emotional responses to fictional characters, as if they were real. But not everyone. Disturbing events in fictional texts often trigger real life emotions. But not for everyone. Humanists bring this experience to AI conversations. As I also tweeted recently, why are we worrying about AI explaining how to rob a bank when there are movies galore that already portray such antisocial behavior?

I think much of the concern about human reaction to AI chatbots would be mitigated without anthropomorphizing the LLM’s interface. But I doubt this will happen. The “I” draws users in, and sometimes they swoon.

“Chatbots will always be old fashioned. AI will always lag behind human verbal invention. AI will never rap in any respectable way. AI will never fully absorb culture, especially youth culture.”

—Hollis Robbins

Regarding language, I think it will become clear that chatbots will always be old fashioned. AI will always lag behind human verbal invention. AI will never rap in any respectable way. AI will never fully absorb culture, especially youth culture. It will always lag. I’ve also written that specific and local cultural knowledge will become more valuable in the AI era. Nobody yet knows what cultural competence will be in the AI era.

I was delighted to share your book Forms of Contention here. Describe a bit about your interest in African American literature and its effect on you.

I was delighted you liked it and thank you! I was not expecting that my scholarly career would be on Black literature. When I began my doctoral studies at Princeton in the late 1990s, I was reading deeply into canonical British and American works by Austen, Wordsworth, Dickens, Hardy, Melville, and Hawthorne, wondering how the development of new state bureaucracies and bureaucratic structures found their way into literary plots. And in fact they did, and I wrote a pretty good dissertation about it that I’ve never published.

But reading an unpublished nineteenth century novel by an enslaved Black writer, Hannah Crafts, discovered by Henry Louis Gates Jr. in 2002, I was startled by how much her close reading of Dickens mattered to writing her own novel. Nobody else was studying this.

So my expertise is how writers such as Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Harriet Wilson, Frances Harper, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charles Chesnutt, and many others worked with and built upon British and American works to create something entirely new.

My book on the African American sonnet tradition is an outgrowth and tying together of all of my scholarship: you might think of the tightly structured fourteen-line sonnet, bound by rules and conventions, as a little poetic bureaucracy that Black writers enjoyed playing with, needling, and complaining about as much as anyone.

Regarding your collaboration with Henry Louis Gates Jr., it seems an ever-increasing amount of academic—and even popular—work is collaborative today. How can scholars and other writers work well with others?

Skip Gates is one of the most kind, brilliant, and generous scholars I’ve been fortunate to work with. When I reached out to tell him that the writer of the manuscript novel he’d found, the one by Hannah Crafts, was using Dickens to tell her story—which had been noticed by none of the scholars of African American literature to whom he had shown the manuscript—he understood immediately how important an outsider perspective would be to identifying her. At the time there was no trace of her.

Another scholar I began working with, Gregg Hecimovich—also relatively new to African American scholarship at the time—picked up some of the loose threads, and ten years later, as a result of some extraordinary archival work, identified the novel as indeed written by a brilliant enslaved woman who escaped to tell a fictional version of her story. His book, The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts, is coming out this fall.

The key to collaborative work is not to have a huge ego and to be enthusiastic when others see things you didn’t see or say things better than you would have said them.

“The key to collaborative work is not to have a huge ego and to be enthusiastic when others see things you didn’t see or say things better than you would have said them.”

—Hollis Robbins

What does it look like to work well with readers and others who encounter your work: the friendly, the hostile, all-comers?

Skip Gates has regularly faced a certain amount of hostility—much of it jealousy—because he has built for himself an academic career that is a combination of extraordinary scholarship, collaboration, entrepreneurship, and fundraising to build the premiere center for Black scholarship, The Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard.

He’s also a documentary filmmaker on the side, right now mostly working on his hit show, Finding Your Roots. Many people wonder how he has the energy to do it all! I’ve collaborated with Skip on several books. I generally do a first draft. He totally rewrites it and makes it 100 percent better. I then do a third, he does a fourth. We’re both fact checking meticulously. And at some point we call it a day and share the credit. It’s a wonderful process.

You also studied with the legendary Richard Macksey at Johns Hopkins. What was it like working with him? And how did he ever find anything in that astonishing 51,000-volume personal library of his?

Dick Macksey was the kindest and most promiscuously widely read person I have been fortunate to know. I’ve known plenty of kind, widely read individuals! But there was something so very unexpected about Dick’s allusions.

He could compare Borges to a moment in Shakespeare and lurch to Dr. Seuss and a German comic strip to Sappho to something his cat must have been thinking about the formulation of French verbs. You never knew where the conversation would end up.

Honestly about his books, though, once after finding something shockingly rare, some eighteenth-century volume signed by the author just sitting on a table (it might have been Rousseau, it might have been Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy), I put the details out of my mind immediately. I was so worried I’d be tempted to pocket something, like a signed note by W. B. Yeats or a thank-you note from Rene Girard. So I seriously can’t tell you what I’ve seen!

You seem to have your finger on several pulses at once, unless at some level they’re all the same: nineteenth- and twentieth-century American literature, pop culture, and technological advances, such as ChatGPT. Your Twitter feed aggregates it all. How do you integrate all these disparate interests? Is there a unified theory of Hollis Robbins’s mind?

The unified theory of my own being in the world is that I am most comfortable at a critical distance from things. I am wary of overt partisanship. I’ve never marched in a parade or held a sign. I rue the rise of the surveillance state, I’m anti-war, and I don’t understand the left’s recent love for the FBI.

I was raised by atheist libertarians in very rural New Hampshire, outside the traditional fabric of civic life. My sister and brothers and I didn’t belong to a church or synagogue or club or any other social or political organization outside of school clubs.

While I volunteered on many presidential primary campaigns growing up, I didn’t attach myself emotionally to any candidate, and I don’t think I became an official member of anything until I joined a Reconstructionist congregation so my children could go to Hebrew school. I wasn’t going to raise my offspring the way I was raised—always outside, always a little suspicious of required allegiance.

Long ago I came across a line that Emerson wrote in a letter to Thomas Carlyle in 1839, complaining that the great New Hampshire senator Daniel Webster had corrupted his intellectual honesty by partisanship: “He has drunk this rum of Party too so long, that his strong head is soaked, sometimes even like the soft sponges.”

Seeing so many intelligent people in New Hampshire go crazy every four years during primary season, I vowed to stay away from that rum. I didn’t read Obama’s campaign biographies when I saw everyone swooning. The benefit is not being swept away by the next thing and keeping an independent mind. The cost is perpetual outsiderness.

Finally, as a busy educator and writer, what’s your one best productivity hack?

Save time by not watching TV news! I was lucky enough to work in TV news in college and just after, first as a pre-interviewer for a PBS interview show, back in the early 1980s, doing initial interviews with scheduled guests—typing up all the answers to give to the talent so they’d know the shape of the answers before the “real” interview—and later as a researcher for ABC News in the London bureau, and then as an overnight newswriter for WCVB, the ABC News affiliate in Boston.

“What you see on TV news is a tiny fraction of what you could find out by other means. . . . Turn it off!”

—Hollis Robbins

I’ve known for four decades that what you see on TV news is a tiny fraction of what you could find out by other means. So except for election night and live breaking news I never watch TV news. It’s the most inefficient way to learn anything about anything. Everyone is drinking and selling the strong rum of party and their heads are soft sponges with perfect shiny hair. Turn it off!

Instead I follow people on Twitter with something to say, people with with as disparate perspectives as Balaji Srinivasan, Ibram Kendi, Alice from Queens, Matt Stoller, Samira Sawlani, Global Times (Chinese State Media), the World Socialist Web Site, Liam Bright, Sohrab Ahmari, you, Taylor Lorenz, Zaynep Tufekci, Diabetic of Enlightenment, Guster, and MC Hammer.

I’m blocked by Cass Sunstein, it seems, because of my opposition to nudges. Whatever. The point is that reading interesting views—like yours!—is a much better use of my time and quieter!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Fascinating conversation, thanks Joel. (“Turn it off” is right; I quit TV news going on four years ago and stopped following most partisan pundits as well. The air is much clearer and fresher now.)

Such a fun interview! And this sentence, wow! - "The unified theory of my own being in the world is that I am most comfortable at a critical distance from things."