One Tongue to Another: Found in Translation

Bookish Diversions: Orwell in Zimbabwe and Eastern Europe, AI Limitations, Translation Challenges, Rediscovering Seneca

¶ Orwell’s trip to Africa. A group of authors in Zimbabwe has teamed up to translate George Orwell’s Animal Farm in Shona, the African country’s dominate language. What motivated the effort, which culminated with a June publication after eight years of work?

“Animal Farm has long been one of my favorite novels,” said team lead Petina Gappah when first announcing the project. She was barely a teen at boarding school when Gappah picked up Orwell’s dystopian “fairy story” in which the animals stage a barnyard coup and overthrow the abusive farmer, Mr. Jones. The story left a mark.

“The animals’ revolution against man was so pure, so noble, and so right,” she said.

Then for that revolution to be betrayed in such a callous manner by their own comrades was just so wrong and so unjust. My 13-year-old self found the end of the novel almost unbearable. I finished it and burst into tears.

Despite the cultural divide, the book connected. And Gappah, now a successful lawyer and novelist, wanted to push it further.

Over a decade ago a Zimbabwean newspaper serialized the book for an eager audience. “It was a smashing success,” said Gappah. But that release was in English. Until now the book has never appeared in any of Zimbabwe’s indigenous tongues. With its translation into Shona complete, Gappah and her team also plan to publish editions in Ndebele and Tonga.

What explains the interest? “Translating Animal Farm into Shona makes perfect sense,” said Oxford University’s Tinashe Mushakavanhu. “Historically, Shona novelists have used animal imagery to conjure up worlds of tradition and custom, and also to examine human foibles.” With such cultural precedents, Orwell always stood a good chance of connecting. That’s especially true when considering the foibles under scrutiny.

The same year Gappah read Animal Farm her class studied Soviet Russia. “I came to understand that Animal Farm was an allegory for that tainted revolution,” she said. “Over the years, I have come to see that this touchstone novel is about all manner of revolutions, including the one in my own country.”

Events in Zimbabwe have eerily echoed elements of the story with fallen strongman Robert Mugabe mirroring Orwell’s porcine antagonist Napoleon, the arrogant pig who seizes control of the farm following the insurrection and becomes everything the terrible Mr. Jones represented—only worse. “Like the pigs in Animal Farm,” said Gappah, “Zimbabwe’s leaders have hijacked a revolution rooted in righteous outrage, not only for personal gain but also to remain in power with no accountability to the suffering people who put them in power.”

The title chosen for the translation plays off the original but amplifies the link to Zimbabwe’s revolution and creates a powerful interpretive lens for the book. “The title, Chimurenga Chemhuka, is poignant and a direct reference to Zimbabwe’s liberation war,” explains Mushakavanhu. “Chemhuka (animal) Chimurenga (revolution) . . . connect[s] the book to the country’s larger struggles for independence, commonly known as Chimurenga.”

¶ Animals behind the Iron Curtain. Since its original publication in 1945, Animal Farm has spoken to people living in the aftermath of revolution. While it’s now been published in over seventy languages, the most recent including both Shona and Scots(!), the first translations were actually Eastern European, meant to travel behind the Iron Curtain.

Gappah was right: Animal Farm was about the Soviet revolution as much as it was about all revolutions, and readers in Eastern Europe resonated with it every bit as much as she did—for the same reason.

Two weeks after the book’s release, a Russian scholar named Gleb Struve wrote Orwell to express his delight for the book and his desire to translate it. Russians, said Struve, “could read the truth about their country only when outside it.” Orwell was game. After all, as Orwell said a couple years later, “One of the most important problems at this moment is to find a way of speaking to the Russian people over the heads of their rulers.”

Despite an earlier-mover advantage, the first foreign language in which Animal Farm appeared was not Russian. That distinction goes to another Iron Curtain nation, Poland. The Polish edition arrived in 1947. Ukrainian followed that same year. Russian came in 1950, Lithuanian in 1952, Serbian in 1955.

Orwell wasn’t greedy about effort. “If translations into the Slav languages were made,” he wrote, “I shouldn’t want any money out of them myself.” Explaining to subjugated peoples how their dreams for liberation went awry was part of the cause—probably the biggest part—and Orwell’s innocuous little “fairy story” was slender as a dagger and sharp as the truth; all it needed was fresh expression in other tongues.

But, then, what took so long? While motivation was high, translation into those Slavic languages took years. And, as mentioned, the move into Shona took eight from inception to publication! Why the wait?

¶ The very human work of translation. You could take this article, drop it into one of many translation apps, and get a passable, automatic rendition in the language of your choice. But it wouldn’t be excellent. In fact, it would likely possess a number of renderings that would hit a native reader as a bit wonky.

Last week I mentioned a new AI model scholars can use to instantly translate ancient Akkadian cuneiform tablets. Even though the system is remarkably accurate it doesn’t work on its own. Rather, as one writer explained, “The AI can provide the raw translation quickly, while the scholar can refine it with their knowledge of historic languages, cultures, and people.” A knowledgeable human is still necessary to complete the process and ensure a quality passage from one tongue to another.

“Languages do not relate to one another in straightforward, one-to-one equivalences, not even the most cognate ones,” says Translators Association co-chair Rebecca DeWald, “so they cannot simply be plotted in a table of x in this language equals y in the other.”

Serious translation is a series of judgment calls. All the variables that make speech rich and expressive in one language are potential landmines in another: syntax, style, verb tense, vocabulary, tone, mood, metaphor, and more. What works in one world falls flat in another. It’s up to the translator to bridge the chasm between cultures. Who knew, for instance, that Hebrew has multiple ways of rendering a simple garden delight, the fig? Says Joanna Chen,

In Hebrew, the words are meticulous: the verb le’erot, for example, which refers to the act of plucking figs from a tree, is grounded in the word for light, orr, since figs must be picked as early in the day as possible.

Deciding on the relevance of such nuance is one thing, deciding how to render it yet another.

“Each language is a world unto itself and has been at least since the destruction of the Tower of Babel,” writes Tess Lewis in the Hudson Review. As a result, “Every translation is founded on an interpretation.”

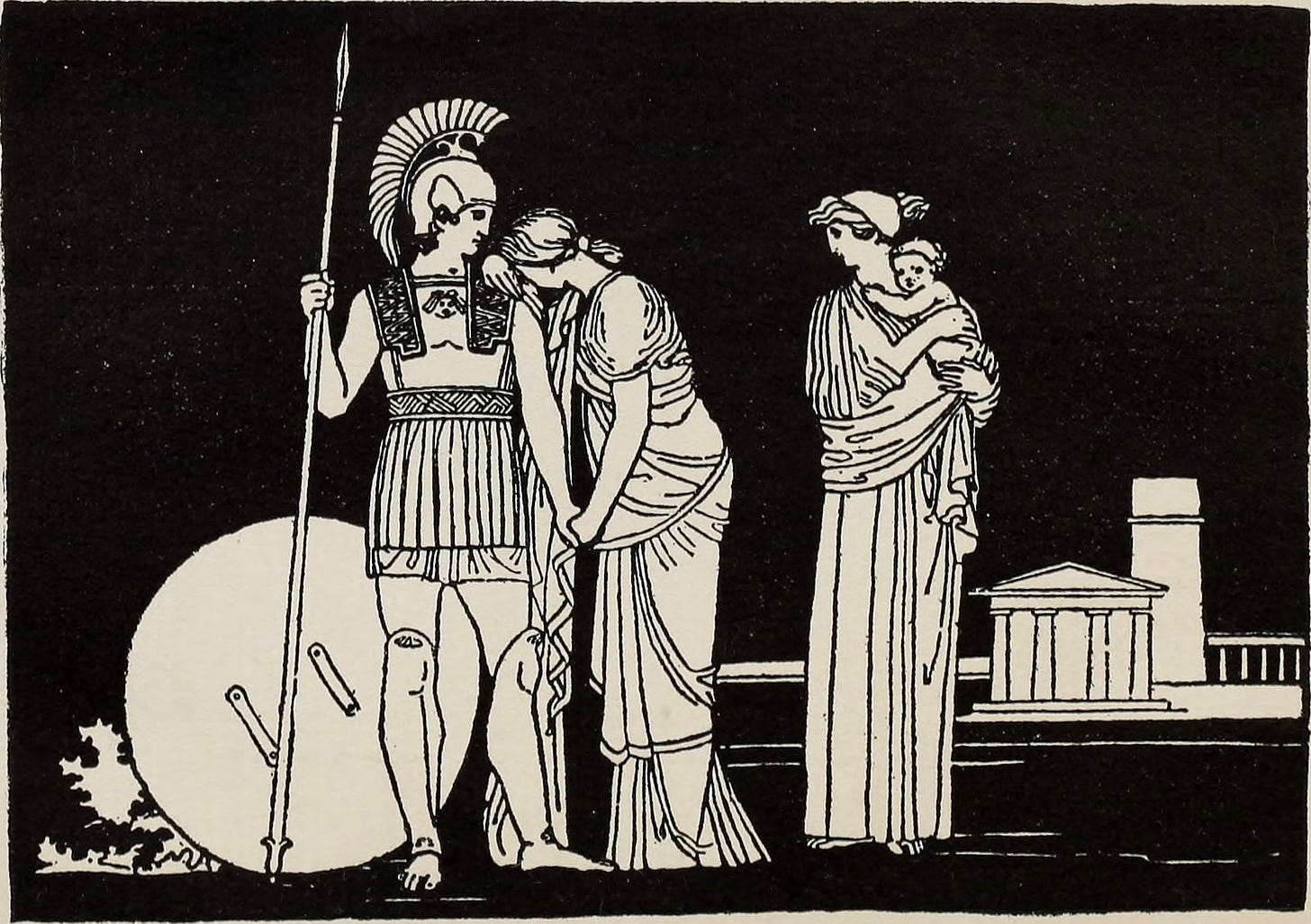

Classicist Emily Wilson, noting a hundred different English translations of Homer’s Iliad, offers several comparisons of just one passage to demonstrate how diverse those judgement calls can be. Here are four versions of the scene in which Hector hands his child to his wife Andromache before heading out to war, starting with Alexander Pope (1715):

He spoke, and fondly gazing on her charms,

Restored the pleasing burden to her arms;

Soft on her fragrant breast the babe she laid,

Hush’d to repose, and with a smile survey’d.

The troubled pleasure soon chastised by fear,

She mingled with a smile a tender tear.

The soften’d chief with kind compassion view’d,

And dried the falling drops, and thus pursued:

”Andromache! my soul’s far better part,

Why with untimely sorrows heaves thy heart?

Samuel Butler (1898):

With this he laid the child again in the arms of his wife, who took him to her own soft bosom, smiling through her tears. As her husband watched her his heart yearned towards her and he caressed her fondly, saying, “My own wife, do not take these things too bitterly to heart.”

Robert Fagels (1990):

. . . So Hector prayed

and placed his son in the arms of his loving wife.

Andromache pressed the child to her scented breast,

smiling through her tears. Her husband noticed,

and filled with pity now, Hector stroked her gently,

trying to reassure her, repeating her name: “Andromache,

dear one, why so desperate? Why so much grief for me?

Finally, here’s Wilson’s own version (2023):

. . . With these words,

he gave his son to his beloved wife.

She let him snuggle in her perfumed dress,

and tearfully she smiled. Her husband noticed

and pitied her. He took her by the hand

and said to her,

“Strange woman! Come on now,

you must not be too sad on my account.

Not only to do the various versions function differently in terms of approach and style (rhyming couplets, prose, free verse, and unrhymed metrical verse), but as Wilson points out, the meanings of the renditions vary as well; for instance, is Hector reassuring or scolding his wife? Looking at slightly longer versions of this one passage, Wilson teases out several interpretive variances. “Each of these translations—along with dozens more—suggests a different understanding of the central themes of courage, marriage, fate and death,” she says.

Every translator faces these sorts of issues on every page—in every sentence. And the perils extend well beyond rendering ancient literary works. It’s just as true for translating children’s literature and genre fiction.

Literary translator Sophie Hughes has a wonderful interactive essay at the New York Times that illustrates this challenge. Here’s an original bit from a Mexican murder mystery:

La verdad, la verdad, la verdad es que él no vio nada, por su madre que en paz descanse, por lo más sagrado que él no vio nada. . . .

Here’s how Google Translate renders it:

The truth, the truth, the truth is that he did not see anything, for his mother may she rest in peace, for the most sacred thing that he did not see anything. . . .

The AI version does convey the sense, but not well. In fact, it even misleads somewhat. It lacks verve, drive, and most importantly the character’s desperation, which is an essential part of the passage. Here’s where Hughes landed:

Honest, honest, honest to God, he didn’t see a thing, on his mother’s soul, may she rest in peace, he didn’t see a thing. . . .

The best thing about Hughes’s essay? She takes us into her thought process in this and another passage and shares several alternate versions, along with the various linguistic, aesthetic, and literary factors that led her to choose one final version over the others. It’s a mini-masterclass in how translators think and the problems they’re trying to solve.

The task reminds me of editorial work, which involves helping writers say what they want in way that serves the message, rather than impedes it. Former New Yorker editor and translator Ann Goldstein notes the similarities. “I do think that proofreading, copy-editing, editing, they have to do with an attention to detail, and of course translation is all about attention to detail,” she says. “It’s attention to particular words, to sentences, and how words work in a sentence. It’s about getting everything as right as you can, or what you think of as right, from the way the word is spelled . . . to the way it’s used.”

“To translate is to remake,” says Oxford professor Matthew Reynolds, quoted by Mushakavanhu, “not only in a new language with its different nuances and ways of putting words together, but in a new culture where readers are likely to be attracted by different themes.”

Gappah and her team faced these same challenges with Animal Farm. “Though Chimurenga Chemhuka is mainly in standard Shona,” explains Mushakavanhu, “its characters speak a medley of different Shona dialects—such as chiKaranga, chiZezuru, chiManyika—plus a smattering of contemporary slang. . . . The use of dialects activates the book in a comical way that also leaves it open to different interpretations and connections.”

¶ Rediscovering Seneca. If Gappah’s eight years to finishing Animal Farm seem long, consider the twenty years it took poet Dana Gioia, brother of

, to bring us Seneca’s tragedy, The Madness of Hercules.

Seneca’s letters have received plenty of contemporary attention thanks to the popular resurgence of Stoicism. But his plays, now two thousand years old, have been largely ignored. And yet, as Gioia says, this tragedy speaks to our time:

Seneca’s play is unfortunately prophetic in the way it describes how we, as a society, sacrifice what is most fragile and precious in our pursuit of utopian control over our own bodies and minds, and those of people around us.

Like Animal Farm, The Madness of Hercules sounds unnervingly relevant. And also like Animal Farm’s unique ability to speak to beyond the land and even time of its birth, The Madness of Hercules is available to us today thanks to the singular—often overlooked—labor of translation.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

We speak about "my reading" or "his reading" of a text. Each reading of a text is also a translation of it into the reader's personal worldview. The writer too will see his subject differently on different days. We live in a commentariat! As Mary Oliver says, "The world offers itself to our imagination . . ."

The series that Princeton University Press does on ancient classics is terrific. There is one on Seneca titled How to Keep Your Cool. Beautiful hardbacks with quality paper and inexpensive. Seneca is currently $13.19. All volumes are translated and introduced by top-notch scholars. Wonderfully accessible language.

https://www.amazon.com/How-Keep-Your-Cool-Management/dp/0691181950