All by Ourselves: Redeeming Loneliness

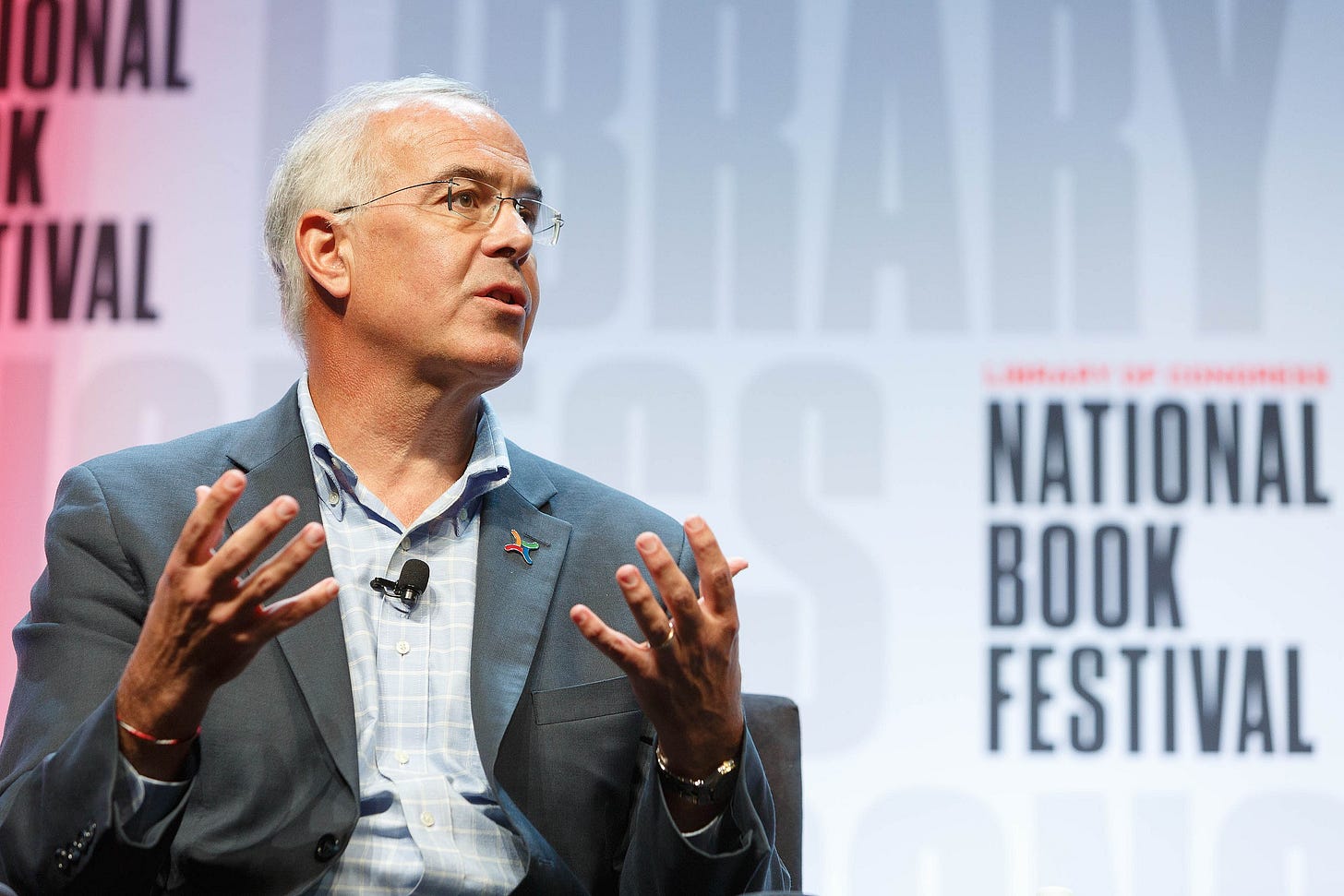

Reviewing ‘This Exquisite Loneliness’ by Richard Deming and ‘How to Know a Person’ by David Brooks

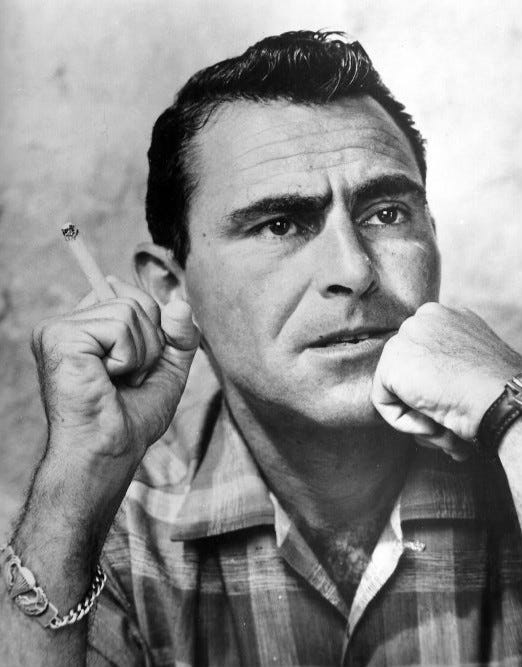

When author Richard Deming’s wife was away for several months, he decided to—what else?—watch the entire original run of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling’s wildly popular science-fiction television show that aired on CBS from 1959 through 1964. Watching one episode a night, he noticed loneliness emerging as a recurring theme of the show.

“That’s a very basic need,” said Serling through one of his characters in the inaugural episode, “man’s hunger for companionship. The barrier of loneliness, that’s one thing we haven’t licked yet.”

Subsequent episodes revisited the theme. My personal favorite? In the eighth, “Time Enough at Last,” the bookish Henry Bemis faces too many interruptions to read and is mocked for his thwarted hobby. Then, as the lucky sole survivor of a nuclear explosion, he finds himself finally, blissfully alone with his books—until he breaks his glasses. Bemis desires solitude but instead gets a desolate loneliness.

As Deming details in his study of social isolation, This Exquisite Loneliness, Serling’s artistic explorations of alienation sprang from his personal experience.

“It wasn’t uncommon for Serling to find himself caught somewhere between groups,” he says. Not only did Serling experience antisemitism countless times, once being barred from a college fraternity because he was Jewish, he was also excluded from a Jewish fraternity because he sometimes dated gentiles. “He always felt like an outsider,” says Deming.

Compounding these formative experiences, Serling endured the traumas of WWII—at one point helping to bury his decapitated friend. He returned from the war shaken and scarred. And his immense success as a television screenwriter in the 1950s amplified rather than ameliorated his sense of loneliness.

In using that feeling as both an impetus and a resource for his art Serling was, ironically, not alone. Deming explores loneliness through the stories of writers and others who dealt with alienation personally and in their art: actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, novelist Zora Neale Hurston, critic Walter Benjamin, psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, photographer Walter Evans, and others.

Deming’s book comes at an opportune time. We regularly hear we’re living amid an epidemic of loneliness. Concerns go back at least as far as 2017 and were exacerbated through the COVID lockdowns of 2020–22. Today about a quarter of the world’s population reports feeling very or fairly lonely, according to a new Gallup survey, with younger people feeling loneliest of all.

Because of documented physical and mental health complications correlated with loneliness, public officials are drawing attention to social isolation. U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has begun a campus tour to stress the importance of connectedness, and New York just appointed daytime TV sex therapist Dr. Ruth Westheimer as the state’s loneliness ambassador.

On the surface, it’s odd we’re complaining of more loneliness than in prior times. After all, we’re more connected than ever thanks to our smart phones and various Web 2.0 tools. But no, not really. Says Deming,

Why does loneliness remain so persistent, despite the ever-proliferating number of social medial platforms? . . . Technology and social media aren’t the cause of loneliness—in fact, they can create a respite or a means of connection for those who are alone—but they can create alternatives to social interaction that slowly starve us. It’s like trying to subsist on cake and soda alone.

I’m not keen on blaming our tools. I can still recall what a boon and balm the Internet was in its early days for isolated individuals looking for the likeminded beyond their local circles. Journalist Jon Katz chronicled one pair of hackers finally enabled to reach escape velocity. He reported their story in his 2000 book, Geeks: How Two Lost Boys Rode the Internet Out of Idaho. Two of my most significant friendships were formed just this way in the late nineties.

Of course, this sort of demographic mixing still goes on today; it’s just so utterly ubiquitous it’s now unremarkable. Familiarity doesn’t breed contempt so much as inattention and neglect. We focus on only the bad, and insist people prove the good from scratch as if their own lives didn’t already testify to the upside.

Still, there is something to it—especially if we fold in the collapse or alteration of social institutions such as church, civic organizations, and work. Our tools operate in the contexts of human relationships. As people increasingly drop out of worship and civic communities and conduct their work primarily online from their already-isolated homes, it’s no surprise loneliness ticks upward, no matter how hyperconnected we seem to be.

But there’s also reason to look beyond technology and even institutions. In How to Know a Person, New York Times columnist David Brooks explores our modern deficits in social skills and moral character—including his own.

Brooks, always self-deprecating, doesn’t pose as superior to his readers. Rather, he uses his own failures as object lessons.

The only real leg up he has over most of us? As a professional journalist he’s got decades of practice asking people questions about themselves. This, as it turns out, is an essential skill. Because most of a person’s reality is trapped inside a few pounds of brain tissue, our most reliable method of gaining access is asking questions—though there are limits to even the best inquisitor.

Brooks mentions interviewing an elderly community leader at a restaurant and finding her stern and forbidding. Then a neighbor, someone they both knew, entered the restaurant greeted her with an enthusiastic, near-violent hug. All her rigidity melted away in a moment. She didn’t feel known or seen by Brooks, but she did by her neighbor.

What keeps us from these sorts of deep bonds? Brooks highlights several ways we diminish others rather than see them for who they are:

We might size people up too quickly and form a hasty judgment.

We might allow our own ego or anxiety to obstruct the relationship.

We might assume people who think differently than us aren’t really thinking—in other words, there’s our way or the way of ignorance, even moral defect.

We might also view people as unchanging and discount the possibility of their growth and development; that is, we freeze-frame people and lock in our personal judgments.

All such behaviors tend to diminish others, and it’s easy to fall into any one of them.

On the other hand, says Brooks, we can demonstrate behaviors that enhance our ability to know others: tenderness, receptivity, active curiosity, affection, generosity, and adopting a holistic attitude. I find this last one especially important and increasingly scarce in our current world.

“A great way to mis-see people,” he says, “is to see only a piece of them.” We latch hold of a negative trait and use that to characterize the entire person. Brooks mentions the case of Pablo Picasso, who some regard as a misogynistic and problematic figure. Brooks quotes Picasso’s biographer John Richardson,

Whatever you say about him—you say that he’s a mean bastard—he was also an angelic, compassionate, tender, sweet man. The reverse is always true. You say he was stingy. He was also incredibly generous. You say that he was very bohemian, but also he had a sort of uptight bourgeois side. I mean, he was a mass of antitheses.

“As are we all,” Brooks concludes. Don’t tell the social media mobs. Or do. Because that’s one fundamental reason we feel alienated and isolated from each other.

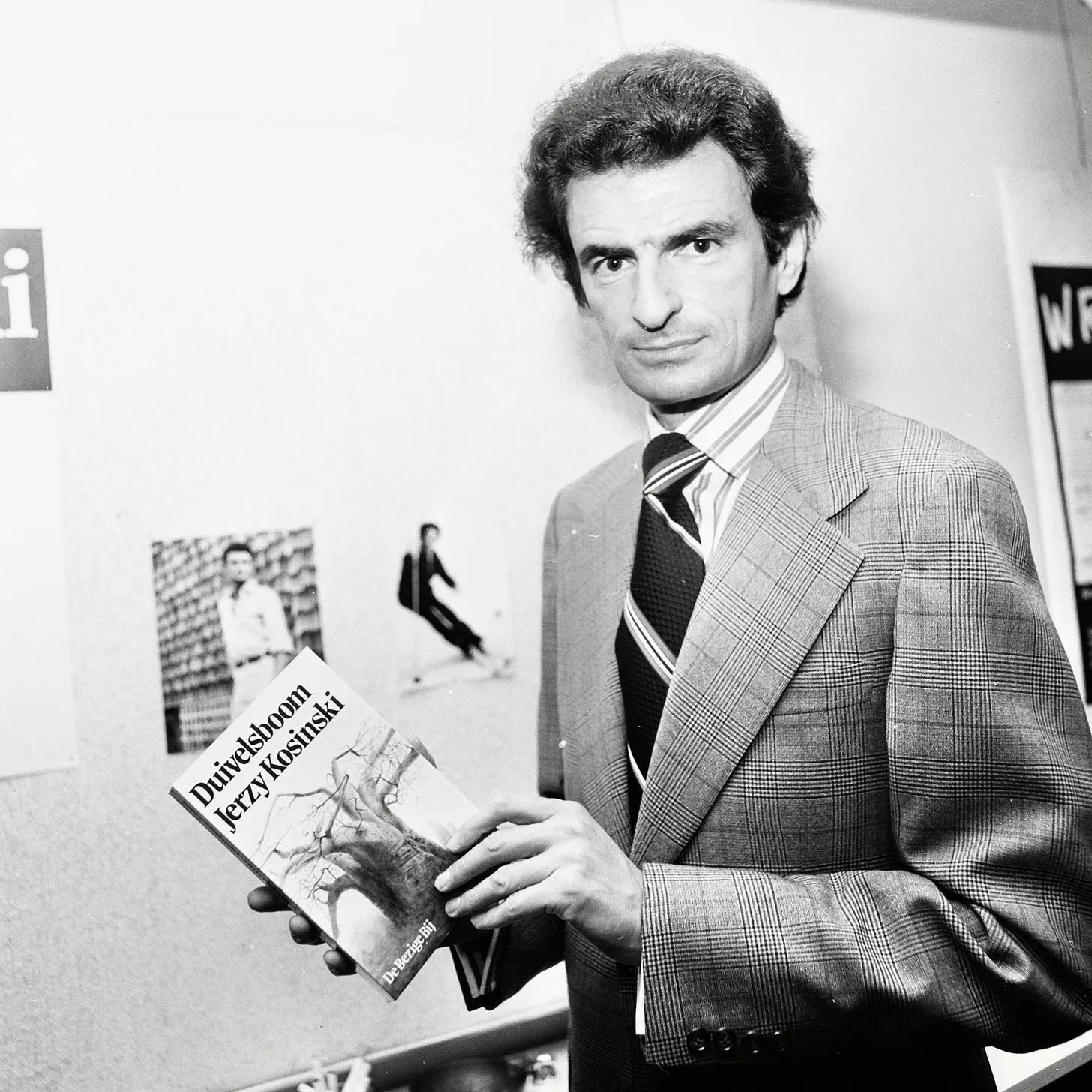

“Americans are no longer the same,” said author Jerzy Kosinski when accepting the National Book Award in 1969. “They wrest freedom from each other. They clearly delineate their places in society. They are angry, violent and abusive. They have become political. And the system responds in turn and invades their freedom.”

This tendency has only amplified across social media with the consequent tradeoff that people self-isolate, self-censor, and shrink back from engagement for fear of attack. The saddest thing you could ever say about a society: “They have become political.”

It’s impossible to see and be seen if we reduce people to whatever cancelable offense we can find. Instead, Brooks calls us to a form of social bravery, to step out of ourselves and make ourselves vulnerable enough to know others and by known by others.

Some of this, as he says, is simply accompanying people, being present in their lives. But some of it comes down to intentionally developing social skills, such as how to manage yourself in a conversation. Doesn’t that come naturally? Not based on some of the conversations I’ve had. Brooks details what it takes to generate the right sort of back-and-forth in the moment.

He also explores the challenge of accompanying people through their struggles, including depression and even suicide. There are several areas where Deming and Brooks overlap, and this is one. Brooks’s best friend took his own life, something he painfully but tenderly recounts, and Deming examines the extreme cost of loneliness in the cases of people such as Philip Seymour Hoffman and Walter Benjamin. For those of us who’ve lived through a friend ending it, Deming and Brooks both offer needed perspective.

Despite how it might seem, there’s something hopeful—even redemptive—in the simple fact of loneliness. “Serling created a universe [The Twilight Zone] whose very surface reveals the loneliness that is part of its atomic code,” says Deming. “Why does he do this? So that we might recognize a commonly shared anguish, and through that discover that the essence of what holds humanity together is the wish to overcome that isolation.”

As Serling himself explained,

Human beings must involve themselves in the anguish of other human beings. This, I submit to you, is not a political thesis at all. It is simply an expression of what I would hope might be ultimately a simple humanity for humanity’s sake.

Deming dwells on this aspect of loneliness throughout the final pages of his book. The sheer mutuality of social pain enables us to meet others in their own suffering because we can so acutely recognize it in ourselves. This leads Deming to conclude loneliness can be “a creative force,” something that not only prompts us to reach outside ourselves but which informs our reaching. It can be for all of us, as it was for Serling, an impetus and a resource.

“We are spurred to know others,” he says, “driven to deeper relationships, because we are not enough for ourselves.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post:

Joel, thanks for this wonderful review. As an introvert and cerebral individual, I have a love hate relationship with loneliness, the internet, etc... There are definitely times I prefer to be alone but the internet has also provide forums (such as this one) where people of shared interests can congregate. I have not read either of these but adding them to my list.

"Familiarity doesn’t breed contempt so much as inattention and neglect. We focus on only the bad, and insist people prove the good from scratch as if their own lives didn’t already testify to the upside."

There's a lot of wisdom in that statement. I'm going to try to keep it in mind as go about my day today.