What Would You Trade for Power and Wealth?

Reviewing Helen DeWitt’s ‘The English Understand Wool’ and César Aira’s ‘The Famous Magician’

“Why,” asks writer and translator Gini Alhadeff, “can’t a grown-up have a really good-looking book with a story she or he could read in about an hour and a half from start to finish?”

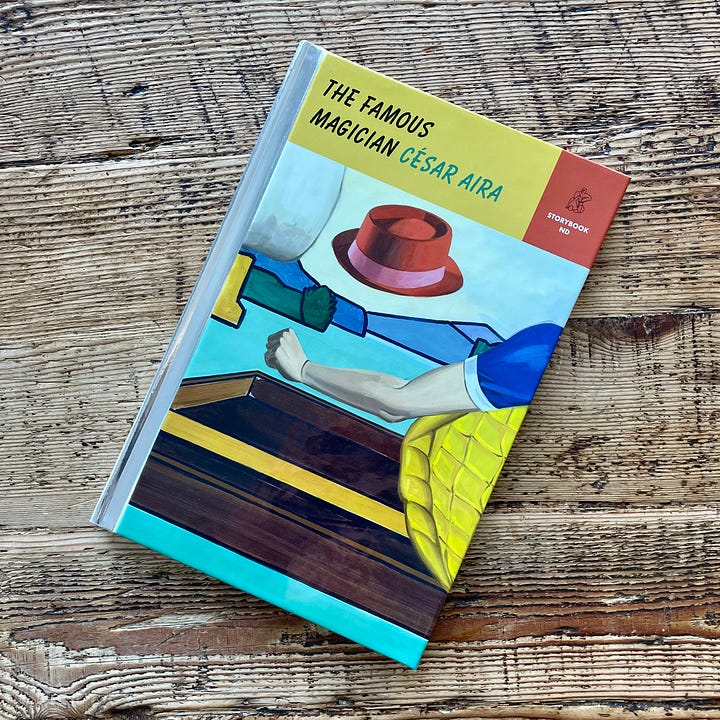

To ensure they can, Alhadeff started the Storybook imprint at New Directions, described as a “series of slim hardcover fiction books” that “aims to deliver the pleasure one felt as a child reading a marvelous book from cover to cover in an afternoon.”

Let’s test it.

I recently picked up two books in the series, César Aira‘s The Famous Magician and Helen DeWitt’s The English Understand Wool. The second came recommended from a longtime friend and publishing colleague. Both concern aspects of the literary life, the first fantastical and strange, the second scandalously down to earth.

A Girl on Her Own

In Helen DeWitt’s tale, a young woman, Marguerite, is raised amid extravagant wealth. Her parents live in Marrakech in a villa with servants, but she spends weeks every year traveling to Paris, Grenada, Venice, and elsewhere as her family pursues various aspects of the good life—as defined by those both hyper rich and hyper cultured.

It’s on one of those sojourns to London as a seventeen-year-old that Marguerite’s life upends. It turns out she lives within an elaborately constructed lie, and once the deception is uncovered her remarkable character comes fully to life in surprising and even hilarious ways.

Unsurprisingly, the revelation of Marguerite’s plight attracts the attention of cultural gatekeepers who know a good story when they hear it. As the perceived victim of an audacious and newsworthy con job, Marguerite suddenly finds herself in demand—which is convenient because she also finds herself out of money.

How will she navigate the opportunity?

Despite the fraudulent foundations of her personal values, Marguerite commits herself above all to avoiding anything mauvais ton—in bad taste. That means a movie of her life is straight out. But a book is different, she reasons: “A book, a text, this is something one can control.”

But can one? Her agent, lawyer, publisher, and editor think so. They have one view of Marguerite and her story. Their role is to help her right the wrong done her by sharing her truth. But what if her version doesn’t align with theirs? As Marguerite navigates the publishing process, DeWitt turns her victim status on its head and shows how the supposed protectors of the supposedly powerless can manipulate and connive for their own ends.

Poor, naive Marguerite is, however, far too clever for that. To explain how she prevails gives away the story, and I cannot deny you the impish delight of her ultimate victory. Suffice it to say that while the English understand wool, Marguerite understands people—and business deals.

Meanwhile, the hero of César Aira‘s The Famous Magician, named after the author, does not.

What’s Better than Magic?

In Aira’s first-person narrative, which functions like a fairy tale, the hero, an author suffering from writer’s block, wanders through a local book fair when he’s accosted by a disreputable dealer named Ovando. César would rather avoid the man, but Ovando corners him with an offer: Would he agree to never write nor even read again in exchange for virtually limitless magical powers?

Unbelievable. But Ovando offers a few proofs of his own powers and César finds himself intrigued. At first he can’t see his way there. “Giving up writing and reading, abandoning my work and my books, would leave me without any consolation. It would be like giving up life itself,” he says.

But then: “What was Literature, what had it been for me if not the protean power of transformation, which I now had the means to transpose to the plane of reality? . . . I wouldn’t be abandoning Literature so much as transcending it.”

Such a momentous change necessitates deliberation, preferably with outside counsel, so César talks with a friend and then his publisher. They attempt to dissuade him from the deal, marshaling several lines of argument. It all comes down to the book’s fundamental question: Is total, unilateral power superior to the partial, provisional power of words on a page?

Both produce changes in the world, but the latter must respect the limits of nature and even the wills of others; counterintuitively, there’s both freedom and creativity within those bounds. The former can be exercised regardless of those limits, which—also counterintuitively—reduces it to something mechanistic and mean.

“They were trying to show me Literature was superior to Magic,” says César. But he’s not so sure. Ovando has given César a deadline to decide. How will he choose? I’ll let you discover his answer to the question for yourself while I return to Alhadeff’s from up top.

Return on Investment

Despite their diminutive size—Aira’s novella is just 60 pages, DeWitt’s 69—these little books turn on a single, large question: What would you trade for power and wealth? Marguerite is faced with trading her integrity and sense of self. For César, it’s whether he’ll forgo the source of real magic, conjuring worlds and moving minds through words, for a false magic that amounts at best to manipulation.

Of course, the terms of such trades are rarely so clear when we strike the deal. But whether we scale it up or down, we’re all faced with versions of the question every day. For the meager investment of an hour or so, we can contemplate the question for ourselves or just relish how Marguerite and César navigate the conundrum.

“Why can’t a grown-up have a really good-looking book with a story she or he could read in about an hour and a half from start to finish?” No reason at all. I recently took both books on a trip from Nashville to New Orleans. I finished DeWitt between takeoff and landing and got a dozen pages into Aira as well, finishing later that evening.

Such enjoyment for a small investment of time: That’s a trade I’d make any day.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

So I'm trying to cut back, and then I read this entry and find descriptions of two books (yeah, short ones, but still...) by writers whose work I have not read before. Two books that sound like fun. If I read them and enjoy them, I'll start poking around looking for their other books, and so much for cutting back.

Ever notice that sometimes if you read a book blog you're kinda like an almost-but-not-quite-recovering alcoholic hanging out in a bar?

This year I've made the 'decision' (because I hate the idea of resolutions), that I'm going to devote more time to creating art, to experimenting, and exploring. The unfortunate consequence is that, with responsibilities and a day-job, there's only so many hours in the day. To do more of anything, means to do less of something else. My reading has taken the brunt of this change of pace. These kind of short reads might be just the thing I didn't know I needed.