‘Love Triumphs over Violence—Eventually’

Cynthia L. Haven on René Girard, Joy Davidman’s Curious Path to C.S. Lewis, Poets in Exile, More

Cynthia L. Haven, a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar, is a literary ambassador and cultural interpreter known for amplifying the work of émigré voices such as philosopher René Girard and poets Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky, both Nobel laureates.

Through her biography, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard (2018), interviews with the scholar in Conversations with René Girard: Prophet of Envy (2020), and collection of Girard’s writing, All Desire is a Desire for Being: Essential Writings (2023/2024), Haven has helped popularize Girard’s concept of mimetic desire and its implications for politics, art, religion, and more.

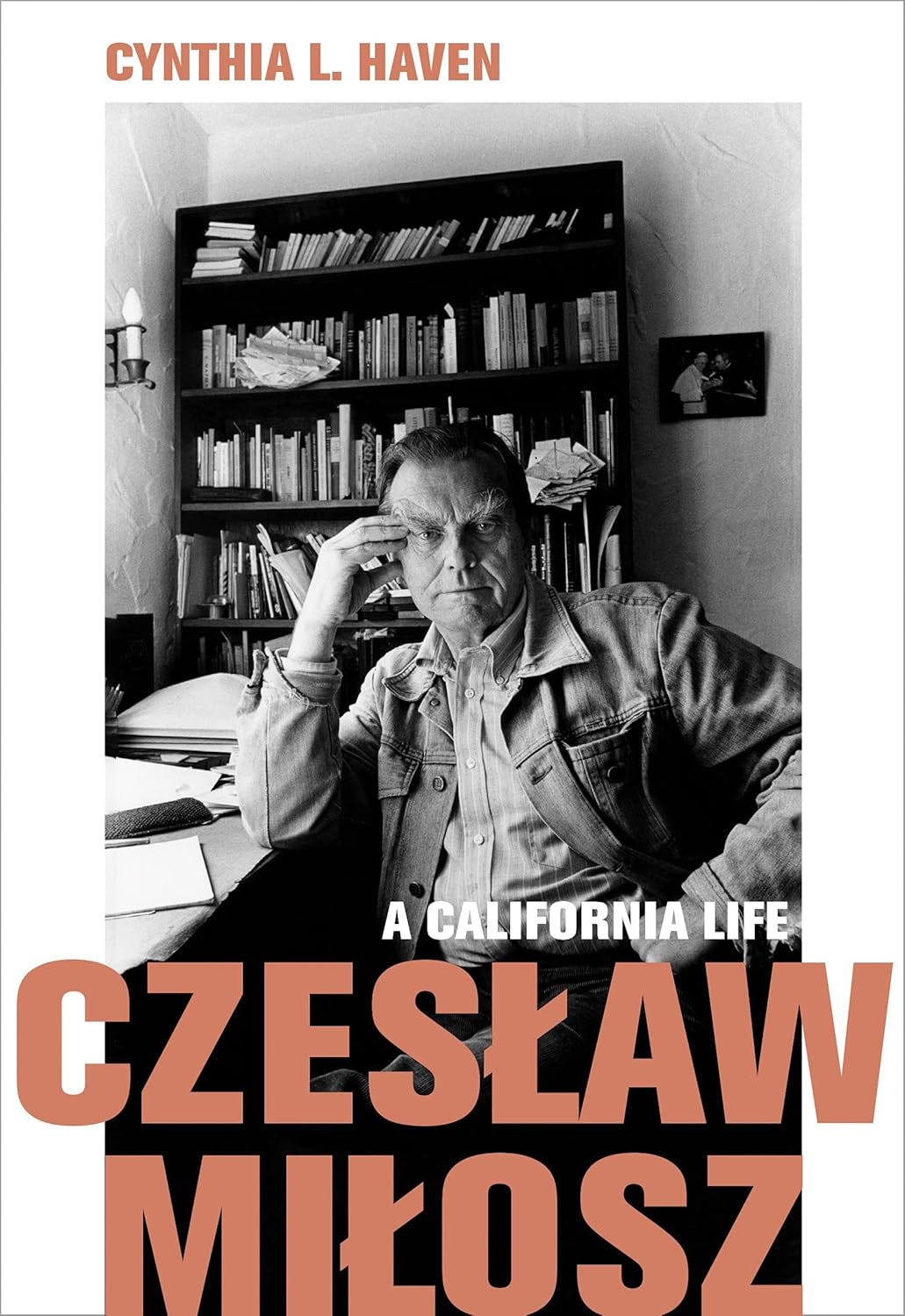

Her profile of a poet in exile, Czesław Miłosz: A California Life (2021), and two previous books, An Invisible Rope: Portraits of Czesław Miłosz (2011) and Czesław Miłosz: Conversations (2006), deepened the world’s appreciation for Miłosz’s life and legacy—and the same can be said for her work on Joseph Brodsky: The Man Who Brought Brodsky into English: Conversations with George L. Kline (2021) and Joseph Brodsky: Conversations (2003).

As those publication dates reveal, Haven practically animates the word prolific, but that captures only part of the picture. As a visiting writer and scholar at Stanford’s Division of Literatures, Languages, and Cultures and a Milena Jesenská Journalism Fellow with the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen in Vienna, Haven has written widely for both English language and international publications, including: The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Times Book Review, The Wall Street Journal, The Virginia Quarterly Review, The San Francisco Chronicle, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Le Monde, La Repubblica, Die Welt, and many others. She also hosts the Book Haven blog and manages the Another Look book club, both at Stanford.

In this conversation, we talk about her relationship with Girard, his ongoing relevance, C.S. Lewis’s wife Joy Davidman, Miłosz and Brodsky, and more.

René Girard is having a moment, thanks in part to you and your work. Who was Girard and why does he matter?

René Girard was a French theorist and longtime Stanford professor, born on Christmas Day, 1923, in Avignon. He died in 2015 at 91, in his Palo Alto, California, home. He was one of the forty immortels of the prestigious Académie Française, where he was dubbed “the new Darwin of the human sciences.”

Why does he matter? He matters because he is one of the few truly great thinkers we have had in our times. His many books take us from our earliest human origins to the end of the world, from the remotest villages of the Africa and Indonesia to the tech empires of Silicon Valley. But mostly he brings us back to ourselves—to our longings, our covetousness, our vendettas, our hopes for a comeuppance against the terrible other, the one we hate and long to topple and displace.

His mind roamed widely across the fields of literature, anthropology, religions, current events, as he explored and fleshed out the distinct phases of his work—mimesis, violence, scapegoating, sacrifice. Too often, journalists, academics, and other readers marshal one segment of his work to support the discussion at hand, while failing to consider the magnificent structure of his entre oeuvre. His explorations show the substance of his intellectual, emotional, and spiritual involvement with twentieth-century history, and his personal effort to come to grips with it.

What are some common misconceptions about Girard’s theories?

Weirdly, people sometimes think René is excusing or advocating violence, rather than unpacking it. They sometimes see him as an ominous figure, obsessively focused on the darkest aspects of humanity. But he was good natured and easy to laughter. Not a dour man at all.

Of course, he is not endorsing violence and scapegoating (or sacrifice), although he said both were the ways archaic communities resolved conflict—and too often, the way we try to resolve conflict today. René Girard is not recommending violence. He is observing and describing it.

Another misconception: The takeaway from his theories is not that we should avoid mimesis or human imitation at all costs. We can’t. We’re chasing our own tails if we try. Imitation is how we learn; it’s how we manage to negotiate in a world of others. We will inevitably imitate something. But we can exercise intentionality and awareness about what we choose to imitate. We don’t have to be tossed about by what the mass media offers us, or by what our peer group tells us.

“We will inevitably imitate something. But we can exercise intentionality and awareness about what we choose to imitate. We don’t have to be tossed about by what the mass media offers us, or by what our peer group tells us.”

—Cynthia L. Haven

Give us one story about Girard that makes you smile just to think of it.

I was amused and puzzled at the way he scoffed when I once mentioned Victor Hugo in conversation. My impression was that he didn’t like the grand sweeping books of the nineteenth century. But certainly that wasn’t always the case. He cites Balzac and, in Deceit, Desire and the Novel, devotes a chapter or so to Stendhal—a great nineteenth-century novelist and author of big door-stopping novels. He also writes about Flaubert. Fyodor Dostoevsky was the subject of his book Resurrection from the Underground. Moreover, Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed, was a 700-page staple of his childhood.

Why he scoffed at Victor Hugo, I’ll probably never know.

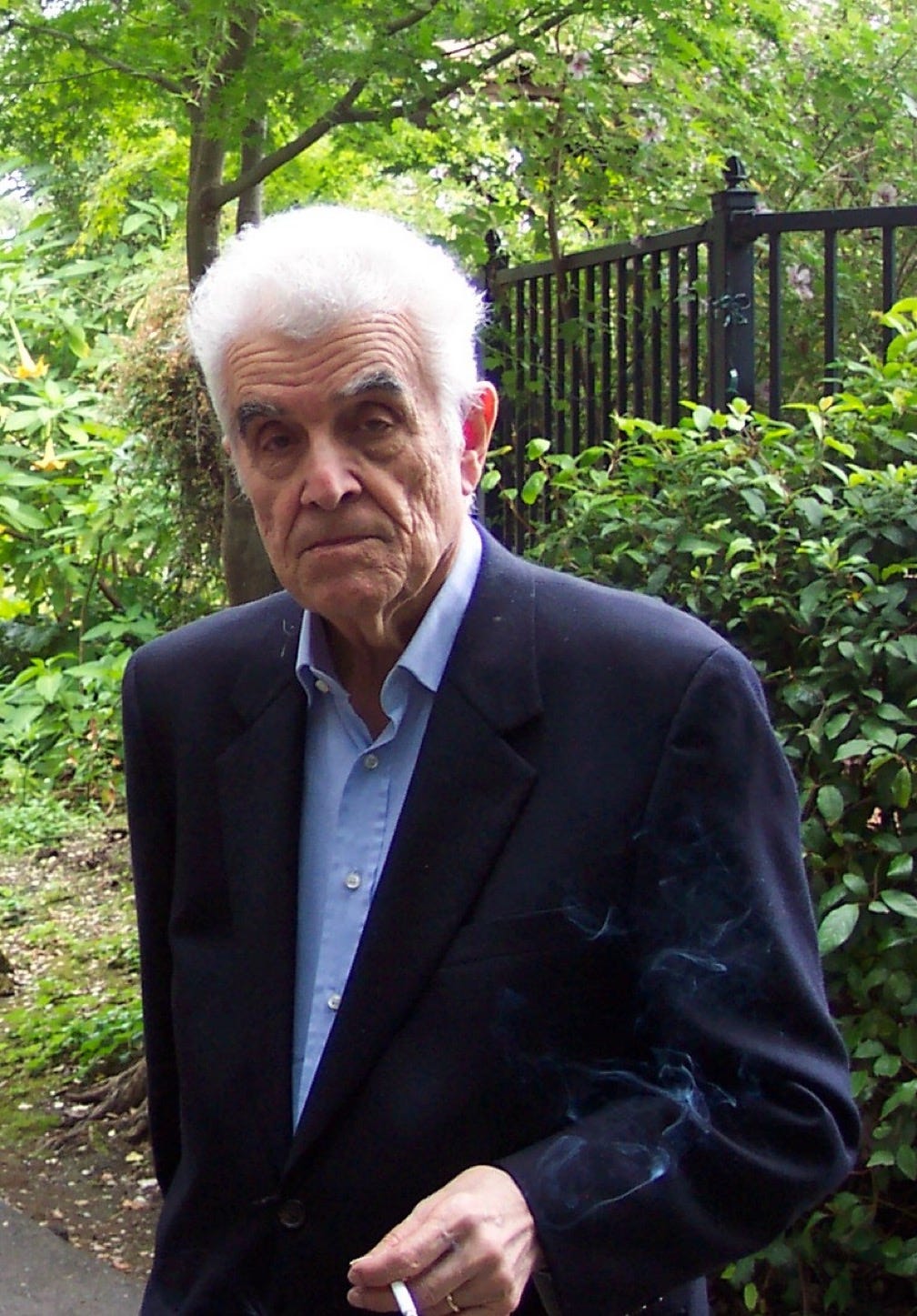

How did you meet?

I knew him long before I knew him. I’d seen him on the Stanford campus decades ago, at the post office or at the bookstore. A large, totemic head with dark, deep-set eyes and shock of thick, wavy, salt-and-pepper hair. I seem to remember a brown leather briefcase, of the professorial kind that disappeared circa 1970, with buckles and straps and usually brimming with papers, letters, and folders. I found out decades later who he was, and began writing about him. We became friends.

Mostly, I remember his charm and our long, leisurely, often unremarkable conversations—unremarkable, except that he was there, with his sagacity, good humor, his kindness and insight. It turned out to be one of the most important and foundational friendships of my life.

What was one quality you encountered in person that comes through most in his books?

Oddly, gentleness—though it often doesn’t come through in his books! He was fierce and articulate in defending his ideas, but wise, provocative, playful, and even impish in conversation. It was a warm, witty, and unequal friendship; his deep courtesy kept the inequality from ruffling the conversation.

“What shall we talk about today?” he would ask when I visited. The white couch in living room. The rose-colored velvet Louis Quinze chair that had belonged to his father, Joseph Girard, who had been the curator of the Palais des Papes. This was the setting of our tête-a-têtes.

What is Girard’s most under-appreciated contribution to philosophy and literature?

It’s tempting to say Achever Clausewitz, his final 2009 book, called Battling to the End in English. It was my introduction to his work, the book that was going to press when I met him. Not everyone likes it; it’s an end-of-life book written as his health was failing. Yet it has a special place in my life and thought.

The alpha and the omega: His work began with imitation and concluded with terrorism, jihad, global warming, and nuclear warfare. His passages on Imitatio Christi, “the imitation of Christ in order to avoid the imitation of men,” are from another world. So are his reflections on the madness of Hölderlin.

Ultimately, it’s not a question of which of his books you read, or how inventive you can be in interpreting his words, but whether you can practice what he preaches. There’s little point in poring over the theory if you still covet your neighbor’s plug-in hybrid or hate your boss in the next office cubicle. Do you still have “enemies”? You can give a great lecture on Girardian theory and still go home and kick the cat.

“There’s little point in poring over the theory if you still covet your neighbor’s plug-in hybrid or hate your boss in the next office cubicle. Do you still have ‘enemies’? You can give a great lecture on Girardian theory and still go home and kick the cat.”

—Cynthia L. Haven

The way to break the cycle of violent imitation is a process of imitating Christ’s renunciation of violence. Turn the other cheek, love one’s enemies and pray for those who persecute you, even unto death. Love triumphs over violence—eventually. But it may not be the peaceful transition some imagine. “Since they do not see that human community is dominated by violence, people do not understand that the very one of them who is untainted by any violence and has no form of complicity with violence is bound to become the victim. But we must see that there is no possible compromise between killing and being killed.” Our blindness is not innocent; humankind has a huge stake in violence and “people fail to understand that they are indebted to violence for the degree of peace that they enjoy.”

It’s important that Girard points a way out. Imitating something greater than yourself, beyond the circles of rivalry. Otherwise, you are pulled back into the world of imitating your neighbor, wanting what your neighbor wants—or is.

You’ve done some interesting work on C.S. Lewis’s wife, the American Joy Davidman. How did she end up in England, soon to marry Lewis?

It was hardly “soon.” Their correspondence began in 1950, and they didn’t meet until 1952—several years and a lot of travel before they married in 1956. Most people would consider six years a long courtship.

William Nicholson’s 1989 play Shadowlands intimates she had a master plan to bag the bachelor C.S. Lewis from the outset. That is doubtful. They began as penpals, but there was an urgency behind the scenes. She and her husband William Gresham had been prominent members of the Communist Party. Gresham was an abusive and alcoholic husband as well, a different kind of urgency.

Davidman had been a strident associate editor of New Masses and active in the pro-communist League of American Writers. She had also had an unsuccessful stint in Hollywood as a scriptwriter. The couple was prominent enough that it wouldn’t be hard to imagine both being summoned to testify before Sen. Joe McCarthy. At the time of her first flight to England in 1952, Congress was issuing subpoenas to another volatile husband-and-wife writer team with Hollywood links: Dashiell Hammett and Lillian Hellman.

The red scare gets a bad name, and it should, but people don’t remember how terrifying it was to see half of Europe swallowed by a totalitarian ideology, right after the Allies had trounced Nazism. It must have felt like the whole world was cracking up, psychologically, politically, morally. Well, Czesław Miłosz’s 1953 Captive Mind tells that story.

Davidman’s efforts to stay in Britain were likely driven by the House Un-American Activities Committee. When I read Davidman’s story and checked the dates, it was obvious. I wrote about it in The San Francisco Chronicle in 2006. I was surprised to find that no one seems to have made this connection.

Incidentally, I experienced some of this fear close to home. My Hungarian immigrant grandparents had been party members in the 1930s. My sister and I were taken aside as children and warned by our mother that we were never to reveal that to anyone. That’s how scary it was, even decades after the hearings. Well, everyone is dead now. Communism is dead, too. I think we’re safe.

“People don’t remember how terrifying it was to see half of Europe swallowed by a totalitarian ideology, right after the Allies had trounced Nazism. It must have felt like the whole world was cracking up, psychologically, politically, morally.”

—Cynthia L. Haven

Today Davidman’s legacy is intertwined with Lewis, but she had a notable literary career before their meeting. What are some highlights?

She received the most prestigious award a budding poet can receive—the Yale Younger Poets Series Award—for her 1938 poetry collection, Letter to a Comrade. Sylvia Plath would have killed for that honor.

A year later, she was named joint recipient—with Robert Frost—of the $1,000 Loines Memorial Fund. She wrote two novels. Her final work, Smoke on the Mountain, is a vivid, provocative interpretation of the Ten Commandments. It’s still in print, I think. Somewhere in my mountains of stored books I have that volume.

She inspired what some critics see as Lewis’s greatest work, Till We Have Faces, as well as being its dedicatee (as he was hers in Smoke). One can make a plausible case that she is the model for its tough and invincible heroine, Orual.

Who were Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky? What’s their relevance today?

Two Nobel poets. Two friends. Both will turn your world upside down. Truly original thinkers, rooted in times and circumstances that have disappeared. Miłosz from the pre-World War I empires of Central Europe, Brodsky from the now-defunct Soviet Union and Stalinism. I had the privilege to know both.

They are endless. That is their relevance. I don’t see any way that they are “dated” although intellectual fashions come and go. We will never get to the bottom of them. That’s what makes them so much fun.

What’s one work from each that belongs on our nightstand?

I’m going to say something controversial.

Joseph Brodsky, Selected Poems with Penguin Modern Classics way back in 1973. It is the book that made his reputation in the West, after his 1972 expulsion from the USSR. It was my first encounter with him—long ago at the University of Michigan. There’s a purity and pain in these early poems. A blast of cold Russian air in a time of navel-gazing poems about the self, about your divorce, your feelings, your childhood injustices. He broke that model wide open with poetry that (gasp!) rhymed. In the intense musicality of his poems—not always evident to Western ears—we could hear the faint whisperings from a faraway world behind the Iron Curtain, perceivable even through the scrim of translation. The stakes were always high for him.

For Miłosz, I would have to say The Collected because I want all the poems, including his Last Poems which will someday be absorbed into an expanded Collected—along with poems written during his postwar diplomatic stints in New York and Washington D.C., Poet in the New World: Poems, 1946–1953. It has just been translated by Robert Hass and David Frick. It will be out in February with HarperCollins.

I give the prize to Bells in Winter, 1978. It was the stunning jewel that made Milosz’s reputation in the West. It is the book that earned him a Nobel.

His learning is a vast adventure. I love his probing into heresies: apokatastasis, Manichaeism, gnosticism. He was teaching himself Hebrew in his later years to translate the Bible into Polish. In his eighties, he began to teach himself Lithuanian, the language of his birthplace. “Why?” he was asked. He replied: “Because I think it might be the language of heaven.”

With poets you always have to privilege the poetry. But it’s important to note that Miłosz’s evergreen bestseller, never out of print, is 1953’s Captive Mind. Many would also argue that Brodsky’s prose and essays opened more doors than his poems, which are difficult to translate. His essay collection Less than One created a wider readership for both prose and poetry, but it can be hard for some to hit these thick volumes cold. So I also recommend for newcomers the edited volumes of Q&A interviews I have published:

Don’t skip the Nobel speeches, either (here and here)! As for René, Achever Clausewitz will always have a special place in my heart and mind. I was reading it as I got to know him. That said, Deceit, Desire, and the Novel deals with literature, and that is my first love, as well as my disciplinary field of interest.

“He began to teach himself Lithuanian, the language of his birthplace. ‘Why?’ he was asked. He replied: ‘Because I think it might be the language of heaven.’”

—Cynthia L. Haven

Can you describe a book that fundamentally changed your perspective on life?

I have to pick just one? I’ll be edgy and say Hugo’s Les Miserables, which I read as a kid. The great-hearted novels of the nineteenth century gave moral and humanitarian bearings to a solitary and malleable child. “An education of the heart,” to use Susan Sontag’s words. I think of Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities and, inevitably, A Christmas Carol. The Brontës, too. Much later, The Brothers Karamazov and others. Austen and Jane Eyre.

I do read more contemporary novels as well! Most recently, Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation. A stunning book by an Algerian author, one of the unfortunate writers who lives with a fatwa over his head. I manage a Stanford book club called Another Look—said to be the largest in the world with 3,480 members. We feature a wide range of writers of all kinds. We’ll be featuring Daoud on November 13.

What’s your favorite part of a writing project?

The snappy answer? Finishing it. Or perhaps publishing it. Letting it go. The relief. It’s done. That’s a bit glib, of course. I love digging around, the research, solving puzzles, making discoveries, making connections. It’s heaven when the synapses begin to crackle and snap. You can almost hear them.

Least favorite?

After the initial enthusiasm has passed, the long slog when you begin to wonder, “Why did I start this?” “How on earth am I going to pull this together?” “Why didn’t I go into investment banking or cybersecurity?” The nagging feeling that you’ll never be done and it never will be any good. The constant, relentless—for me—iterations. The paper: Whole forests have been felled for my rough drafts. I weep for the trees.

“I love digging around, the research, solving puzzles, making discoveries, making connections. It’s heaven when the synapses begin to crackle and snap. You can almost hear them.”

—Cynthia L. Haven

What’s one feature of today’s literary culture that peeves you the most?

Its disappearance. The loss of book sections, bookstores, and long coffee-shop conversations about new arrivals in the days before Amazon. The smell of real paper in an old book. Audiobooks and ebooks are second-best in many ways.

But I’m a creature of the present, and so I’m big user of Amazon, too—even though I miss some of the bookstores that were my haunts. The disappearance of Printer’s Ink in Palo Alto, which had a store clerk named River and a friendly brown tabby whose name I can’t recall. Or Chimera in Palo Alto—the old, multistory pine-green house that was a bookstore. Denise Levertov gave a reading to save it when it was on the verge of closing.

You could read books on the shabby couches of Chimera—not usually allowed in bookstores. Of course, you wound up buying the books in the end just so you could read in the privacy of your home, and the staff knew it. That was the strategy!

The problem is that one is often reduced to the choice to being a reader or writer. My writing commitments take all day, every day. I would love a separate life as a full-time reader where, to borrow from Auden, “my double sits writing and does not look up.” Except I want my double to be reading instead!

“I would love a separate life as a full-time reader where, to borrow from Auden, ‘my double sits writing and does not look up.’ Except I want my double to be reading instead!”

—Cynthia L. Haven

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Milton. It goes as well as you would imagine. Or this: an ink-stained wooden table in Luxembourg where Simone Weil, Albert Camus, and Miłosz once gathered under Madame Weil’s roof. I’m still exploring that circle, which was a theme in my “Miłosz Lecture” at the Kraków literary festival last summer. I’m not sure I’d be up to the conversation, but I’d be happy to be a silent fly on the wall.

Here’s another possibility: John Coetzee. Not a talkative guy, however. I admire his provocative stance on animals, which goes way beyond vegetarianism. I happen to share it.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying Miller’s Book Review 📚 please spread the love and share it with a friend!

And if you’re not a subscriber, sign up for regular, free reviews, essays, and more.

Milosz was a poet in residence for a year in my department when I was a graduate student. I was very lucky. And I had a random encounter with Seamus Heaney when we shared a cab to the airport!

Oh, well done! One of the best interviews I’ve read this week, and one to hold onto!