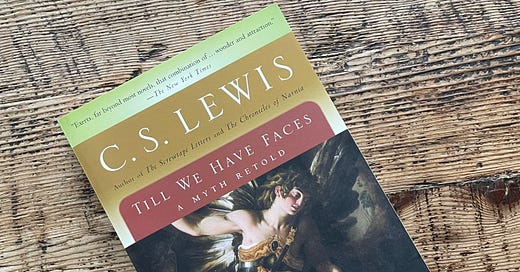

Myth Take: C.S. Lewis’s ‘Till We Have Faces’

Sometimes the Questions We Pose Present the Answers We Seek

The aged queen has stewed in her resentment long enough. As she nears her death, she determines to vent her case against the gods. What can they do about it? “I am old now,” she says, “and have not much to fear. . . . I have no husband nor child, nor hardly a friend, through whom they can hurt me.”

That wasn’t always so. Orual, queen of Glome, once had her beloved counselor, a Greek slave named the Fox, her trusted captain Bardia, and above all her step-sister, the princess Psyche. But the princess was taken from her—taken by the gods—and that robbery forms the crux of Orual’s grievance. To prosecute her case, the queen decides to recount her life’s story, particularly as it pertains to her lost sister.

A Myth Retold

In the spring of 1955, C.S. Lewis struggled with what to write next. He’d come off a long productive stretch during which he’d written and published his Narnia stories, finished his Herculean English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, released his memoir, Surprised by Joy, and even gave the final shape to his most enduring classic, Mere Christianity. His biographer, Alan Jacobs, estimates Lewis generated as many as 700,000 words(!) in this period.

But now the old don was dry. And that’s when joy surprised him again, this time in the shape of Joy Davidman, who would soon become his wife but who first served as his creative and critical counterpart.

The myth of Cupid and Psyche had long interested Lewis. In the standard version of the tale, the mortal Psyche finds herself blissfully wed to the god Cupid, living in a resplendent palace, though under a mysterious condition: Cupid only comes at night and forbids Psyche to look upon him.

Poisoned by meanness and jealousy, Psyche’s two sisters visit her palace and seize upon the strange proviso. The pair sow doubt in Psyche’s mind, urging her to violate the ban, ostensibly to see if this god is who he claims or rather a monster. Following their advice, Psyche lights an oil lamp, inadvertently wakes her husband, and experiences the consequences of his disappointment.

Lewis found the story intriguing but unsatisfying. The tale warranted a different point of view. Thankfully, Joy materialized and one March evening over drinks helped the creatively parched professor tease it out.

The Myth Transformed

As she wrote in a letter to her ex-husband, Bill Gresham,

One night [Lewis] was lamenting that he couldn’t get a good idea for a book. We kicked a few ideas around till one came to life. Then we had another whiskey each and bounced it back and forth between us.

Inspired, Lewis got immediately to work and penned the first chapter of what became Till We Have Faces. It took him just a day. “I read it and made some criticisms,” said Joy; “he did it over and went on with the next.” Within five weeks Lewis was three quarters of the way through the first draft, Joy helping him all along the way. “What I’d give for that energy!” she said.

For his principal innovation, Lewis re-centered the narrative in the perspective of Psyche’s step-sister and stand-in mother, Orual, the eventual queen. He also provided a new setting—a barbarian kingdom somewhere on the periphery of the Greek world—and filled it with an array of supporting characters, none more menacing than the faceless goddess Ungit, the local version of Venus, mother of Cupid, and her temple functionaries.

While the world Lewis weaves feels authentically pre-secular, pre-Christian, and its culture utterly other and foreign, his first-person narration through Orual renders this world not only convincing but also relatable. As Orual tells her story, we sympathize with the apparent injustices she describes when:

Ungit’s priests claim Psyche is to blame for the misfortunes of the kingdom;

the priests take Psyche and abandon her on the mountain as a sacrifice to Ungit and her son;

Orual returns to the site to bury her bones but instead finds Psyche alive, though apparently living under a delusion;

Psyche praises her divine new palace and its trappings, but Orual is denied more than a fleeting glimpse;

Orual is reduced to manipulating Psyche into violating her husband’s unreasonable ban on seeing him, convincing her to stash a dagger and lamp in an earthen jar by their bedside;

as a consequence, Psyche is driven away from her marriage bed and forced to endure a series of impossible trials;

worst of all, the aged Orual encounters a shrine dedicated to Psyche, newly elevated to the status of a goddess, hears a priest recite her sacred story, and finds herself slandered in the telling.

No wonder the queen finally levels her accusation; it’s astonishing she bottled it up so long. But while Orual believes Psyche was living in a delusion after her abandonment on the mountain, her own vision is likewise impaired.

Through a series of visions, Orual discovers her complicity in her own complaint. Nor are these revelations simply a reversal of her indictment. Orual finds her personal trials in the years following Psyche’s banishment doubled as a mysterious participation in her sister’s travails. As the god tells her, “You also are Psyche.” Expressing her grievance turns out to provide its own response. Grace, as usual, goes to the undeserving. “Joy silenced me,” says Orual.

Through it all Lewis weaves a spellbinding account of love and jealousy, hope and doubt, faith and betrayal, and he does so through the strongest character in any of his novels. How’d he do it? Joy revitalized his voice.

Behind the Tale

To transform the nature and import of the original myth Lewis went, as he said in his author’s note, behind the original tale. But in a different sense of the word Joy did the same, working behind Lewis.

“Her part in the book, and there is so much that she can almost be called its joint author, put him very much in her debt,” said Lewis’s student, friend, and biographer George Sayer. Joint authorship might overstate it, but Joy’s role proved indispensable.

“I don’t kid myself in these matters,” she said. “Whatever my talents as an independent writer, my real gift is as a sort of editor-collaborator. . . . Though I can’t write one-tenth as well as Jack [Lewis], I can tell him how to write more like himself! He . . . says he finds my advice indispensable.”

Said Sayer, “She stimulated and helped him to such an extent that he began to feel that he could hardly write without her.”

I’ve now read Till We Have Faces more times than I can exactly recall—at least five times, maybe six, maybe seven. If the actuarial tables are correct, I’ve got several more ahead of me—a delightful prospect. It’s an old companion that still surprises me with every visit. Lewis considered it his best book. It is.

Naturally, he dedicated it to Joy.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

The part that has stayed with me the most from my recent reading is when Orual speaks with Bardia's wife after his death. It challenges Orual's view of herself to the core; and yet the actual connection between the two women is fleeting. They unite and then immediately become hostile again. I'm still mulling this over.

I think one of the things that most struck me in this last reading is how closely Oural’s final conclusion mirrors Job. She is in a way, convicted by her own lament, but the fact that she’s allowed to make it, is as she says, it’s own answer. It speaks so clearly to the power of our attempts at honesty being a way of revealing how many things we hide from ourselves. And yet, the honesty is valuable even as we realize how little we know. The “till we have faces” has always made me think of the passage in 1 Corinthians — our dim understanding being limited until, like Ourual we find we have faces that Someone can bear to look on.