What’s My Point? Consider the Pencil

The Evolution of an Underrated Tool, Plus Its Famous Users: Thoreau, Morrison, Dahl, Steinbeck, More

For years now I’ve used a FriXion erasable pen from Pilot for all my non-digital writing. But recently I found myself stranded without my pen and was forced to use—of all things—a No. 2 pencil, as if I were back in grade school. I loved it!

I enjoyed the slight scratchy sensation of pushing and dragging the sharpened graphite across the page, leaving a slender trail in the shape of whatever letters I chose. People have been reliant on this humble tool since the early modern era, refining it through the centuries and fussing over finding the ideal version.

What goes into a pencil? And what makes it so special?

Get the Lead Out

Though we sometimes call the narrow cylinder at the core of a pencil “lead,” it’s not. Graphite does have metallic properties; it can, for instance, conduct electricity. But graphite is composed of pure carbon, same as diamonds. The differing molecular structure of all those carbon atoms allows one to look good on a ring finger and the other to leave legible marks on surfaces, such as . . . sheep.

The English often receive credit for discovering graphite. Supposedly, a tree fell over in the Cumbrian Lake District in the middle sixteenth century and its upturned roots revealed an underlying mineral deposit that resembled coal. It also resembled lead, which provided the name plumbago from the Latin word for the ore.1

Plumbago proved a linguistic dead end. Though the term persisted in Anglophone use well into the nineteenth century, in 1789 the German scientist Abraham Gottlob Werner coined the more apt term graphite from the Greek for “to write,” graphein, We’ve since dropped the Latinate term, but we’ve retained its import and still misleadingly talk about “pencil lead” to this day.2

While the Lake District discovery did lead to the founding of an important graphite mine, the popular story is also wrong: English use predates the sixteenth century. Monks at the nearby Abbey of Furness used pieces of graphite to mark their sheep, as did local farmers. Monkish use matters because Henry VIII demolished the monastery in 1537 as part of the English Reformation, a generation before the supposed Lake District find. And use can be documented both earlier and further afield.

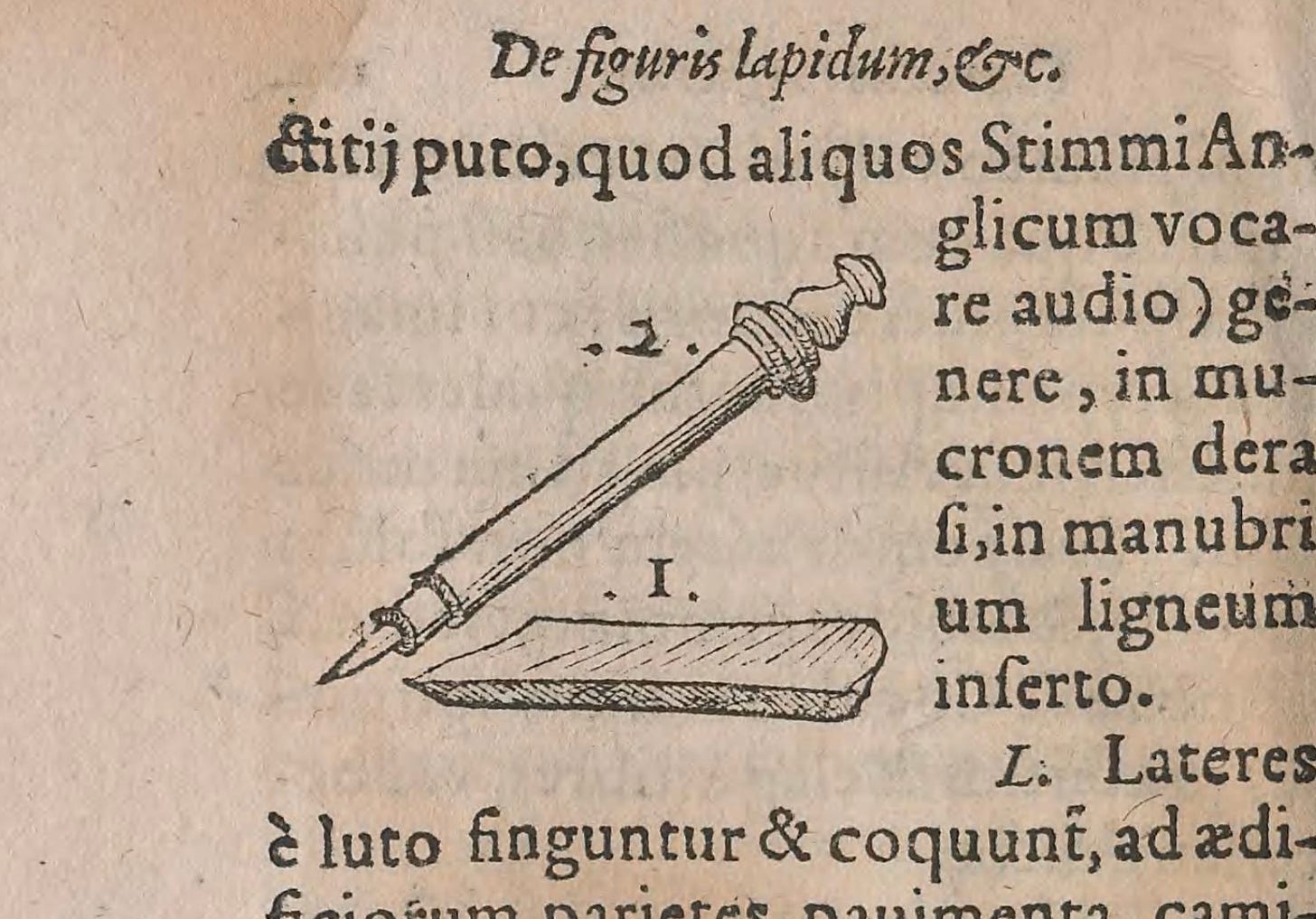

Ancient Egyptians were familiar with graphite, as were the Celts, and the Aztecs mined it for writing purposes. So did the Bavarians. In fact, use in Europe goes back at about a hundred and fifty years before the Cumbrian cache was discovered. Tellingly, the earliest image of a pencil was published around the same time, which indicates predating use.

The woodcut appears in naturalist Conrad Gessner’s 1565 book, On Fossil Objects (full Latin title: De Rerum Fossilium Lapidum et Gemmarum Maxime, Figuris et Similitudinibus Liber).3 The image reveals a knobbed stylus with replaceable graphite tip. At the time, the English were apparently still wrapping pieces of graphite in sleeves of sheepskin or string to keep their hands clean while writing.

Gessner’s pencil wasn’t the only innovation of the period. Around the same time an Italian couple, Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti, bore out sticks of juniper and slid long, slender rods of graphite into the hollow, creating something visually similar to modern pencils. Eventually, people realized multiple grooves could be cut into planks of wood and the graphite rods positioned and then sandwiched inside. Once glued, the individual pencils could be cut from the blocks and shaped as desired—still how pencils are made today.

But an additional development was required to bring us fully into the modern era. All these pencils so far relied on solid pieces of pure graphite. It turns out, however, pure graphite makes an inferior product. It took a war to realize the problem and find something better.

Modern Pencils

The French imported their graphite from England, a convenience that became a crisis when the two nations went to war at the end of the eighteenth century. Luckily, the French had Nicolas-Jacques Conté, a painter, hot-air balloonists, scientist, and inventor.

Conté found he could grind graphite to powder, mix it with clay, and fire it in a kiln to make pencil cores with less actual graphite than used in a pure core. Not only did this ceramic method dramatically mitigate the import challenge, it also enabled Conté to create a superior product. How so?

Pure graphite came in whatever hardness or softness nature supplied when shaping deposits of the mineral eons ago. But Conté discovered, as University of London professor Alan E. Cole says, “the hardness or softness of the final pencil ‘lead’ can be determined by adjusting the relative fractions of clay and graphite in the roasting mixture.”

More graphite yielded a softer pencil, more clay a harder one. Manufacturers could develop recipes for various grades, and thus specialty, “polygrade” pencils were born. The new method also allowed manufacturers to make—not to be overlooked or underrated—cylindrical cores instead of the rectangular ones that predominated as a result of previously cutting blocks of pure graphite down into sheets, strips, and rods.

While Conté’s innovation came first, another pencil maker a continent away independently landed on the very same solution. American graphite deposits were inferior to British supplies.4 U.S. pencil makers compensated by making composite cores, grinding up their graphite and mixing it with other ingredients. Unfortunately, they used all the wrong stuff.

They, says Duke University engineering professor Henry Petroski, “mix[ed] their inadequately purified and ground graphite with such substances as glue, bayberry wax, and spermaceti, a waxy solid obtained from the oil of the sperm whale.” The resultant pencils were, as Ralph Waldo Emerson’s son Edward griped, “greasy, gritty, brittle, [and] inefficient.” Not good.

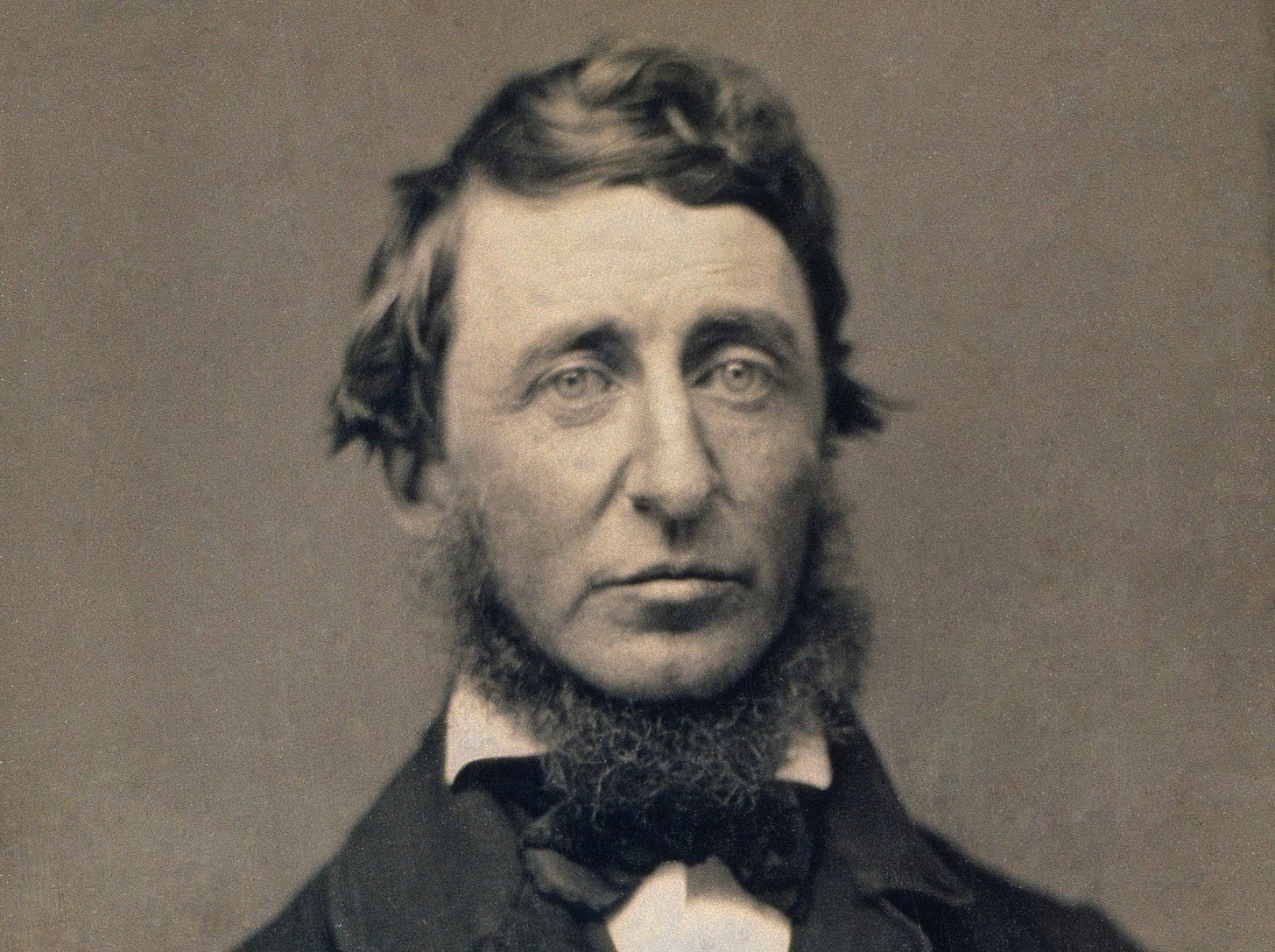

Thankfully, Henry David Thoreau—yes, that Henry David Thoreau—had an idea.

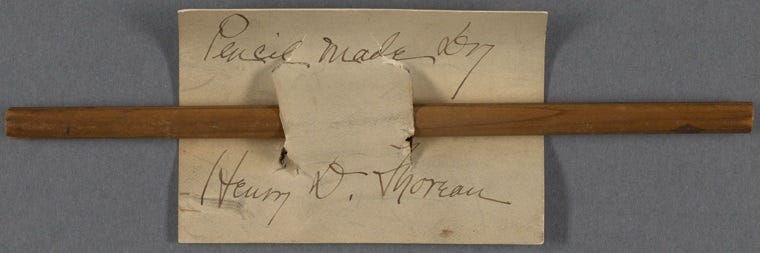

What’s not clear? How Thoreau arrived at his idea. He had two principal insights: (1) pencil makers’ graphite was ground too coarse, and (2) clay would make a better binder than anything that came out of a whale. What is clear? How Thoreau acted on these insights. Conveniently enough, his father owned a pencil factory.

The younger Thoreau developed a mill that would thoroughly grind graphite, and he improved the means for purifying the mineral. Once up and running, his new process yielded award-winning pencils widely reputed to be the best in America.

As Thoreau tinkered with the new method, he found as Conté had, that the ratio of clay to graphite enabled harder or softer, as well as lighter or darker, writing cores. The Thoreaus came up with the grading scale, moving softest to hardest from No. 1 through No. 4. No. 2 pencils—the ones we still primarily use in schools today—were the ideal hardness for a durable core with little smudge.5

Petroski notes that Thoreau made innovations in his process for several years after the initial work. But eventually he quit for Walden pond, and the family stopped making pencils altogether. Instead, they supplied companies who wanted their refined graphite for the new and growing electrotyping business.

You can see how pencils are made today here and here, the first in a fully automated Western facility, the second in a smaller, more rustic factory in Japan.

What’s remarkable is that the manufacture of pencils is, on the one hand, so basic and rudimentary. Yet, on the other, it’s so complex and refined, requiring inputs and skills so diverse, that no one person can actually make one. In his classic essay, “I, Pencil,” Leonard Read famously used the lowly instrument as a case study and explanation of the intricacies and interdependencies of modern, market economies.

Favored Tool: Morrison, Dahl, Steinbeck

Thoreau liked to go on hours-long walks and write on the path. Pencils were the perfect writing tool and writers—whether mobile or stationary—have relied on them for notes, first drafts, manuscript corrections, and more.

When Paris Review interviewers asked editor and novelist Toni Morrison about the physical aspect of her writing process, she referred to her use of pencils. What about a word processor? “Oh, I do that also,” she clarified, “but that is much later when everything is put together. I type that into a computer and then I begin to revise. But everything I write for the first time is written with a pencil. . . . I’m not picky, but my preference is for yellow legal pads and a nice number two pencil.”

Some writers ritualize their use. Children’s author Road Dahl would work in his “writing hut” behind his house “at the top of garden.” Each session lasted about four hours. Before he would begin? He’d sharpen six pencils—“I always use six pencils, and they always have to be sharpened”—and brush the eraser filings off his makeshift lap desk from the last day’s work. When he wanted to procrastinate, he sharpened his pencils twice, once with an electric sharpener and a second time with a pocket knife.

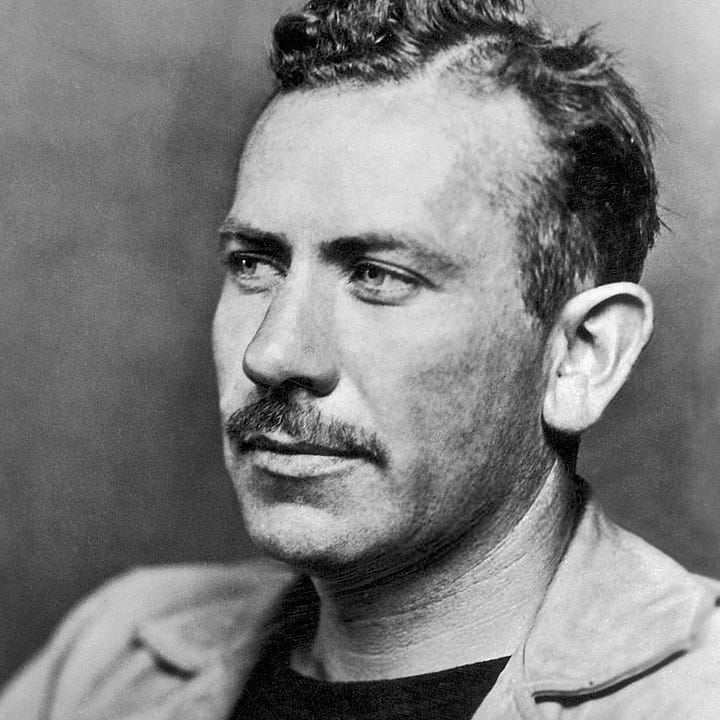

Like Morrison, Dahl preferred yellow legal pads and matching yellow No. 2 pencils—Ticonderogas. John Steinbeck also loved yellow legal pads and was similarly particular about his chosen writing implements. He compared his pencils to “an umbilical connection” between him and the words. He couldn’t function without them; with them, he could endure most anything.

In between wives, in 1949, Steinbeck wrote,

Gwyn has all my books and all the money and the house and the pictures. . . . I have one little room and a tiny kitchen and a bed and a card table and that is all I need with yellow pads and boxes of pencils. This she cannot nor ever will understand. But my new girl understands and likes it and so there we are.

Presumably, this unnamed new girl was Elaine Scott, soon to be Elaine Steinbeck. “He was passionate about pencils,” she would later say as his widow, writing with Robert Wallsten in their collection of Steinbeck’s letters, “about the way they felt between his fingers, about their weight and pressure. He boasted of calluses from holding them.”

The pair quotes Steinbeck on his daily writing ritual. “I sharpen all the pencils in the morning,” he said, “and it takes one more sharpening for a day’s work. That’s twenty-four sharp points.” I take that to mean he started with a dozen, but I’ve also read that he started with twenty-four. Still, the numbers vary wildly, even humorously. Some examples with my emphasis added:

1952: “I like the feeling of the pencil. The second finger of my right hand has a great grooved callus on it into which the pencil fits. And I have an electric pencil sharpener. I use it about 200 times a day.” If he only sharpened his twelve pencil once during the day, we’ve got a large inconsistency here. And sure enough . . .

1951: “The electric pencil sharpener may seem a needless expense and yet I have never had anything that I used more and was more help to me. To sharpen the number of pencils I use every day, I don’t know how many but at least sixty, by a hand sharpener would not only take too long but would tire my hand out.” Sharpening sixty pencils before starting? Sounds like double-Dahl level procrastination. “I like to sharpen them all at once,” he clarified, “and then I never have to do it again that day.” Interestingly, this represents a change in his writing habits, one that seems to have stuck.

1967: “Journalism . . . gives me the crazy desire to go out to my little house on the point, to sharpen fifty pencils, and put out a yellow pad.”6

One reason Steinbeck used so many pencils? He never liked short ones. Once he sharpened them far down enough that the metal ferrule touched his hand, he got rid of them. “I detest short pencils,” he said.

Meanwhile, inventor Thomas Edison actually favored short, fat pencils—about three inches long, so they would fit conveniently in his vest pocket. He had them custom made by the Eagle Pencil Company and purchased them in lots of a thousand. This sort of fussy selectivity, evidenced by Steinbeck and Edison, though not remotely limited to them, represents a feature, not a bug, of pencil culture.

The Ideal Pencil?

This long evolution of the pencil reflects the human desire to optimize our tools. From writing with lumps of raw graphite on sheep and slender sticks of the stuff on sheets of parchment to creating composite cores with gradations of hardness and opacity designed for ever-more specialized uses, we’re not satisfied until we have the ideal instrument.

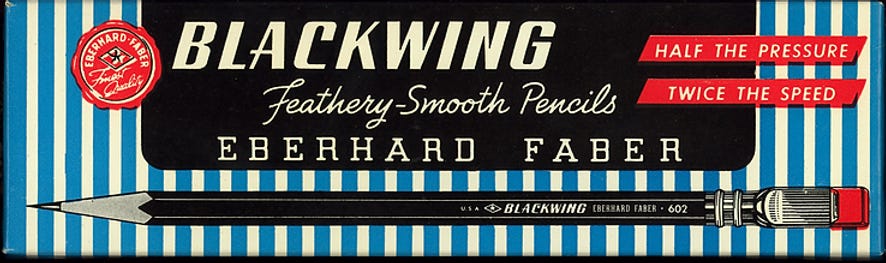

Of course, what counts as ideal is both use and user dependent. Morrison and Dahl loved their No. 2s. Steinbeck’s tastes varied; according to Carter Davis Johnson’s essay on Steinbeck’s pencil fetish, he preferred the Eberhard Mongol, Blaisdell Calculator, and, most famous of all, the Blackwing 602—which has since attained cult status, given its favored use by Vladimir Nabokov, Truman Capote, Stephen Sondheim, Quincy Jones, cartoonist Chuck Jones, and others.

After my enjoyable return to Pencilverse, I decided to purchase a couple dozen for my daily use. I also knew that was a slippery slope. There are a million options and a million opinions. “A pencil that is all right some days is no good another day,” said Steinbeck. Factoring the relative hardness and darkness, the source of the graphite (some people swear by Japanese), the shape of the wooden barrel, the finish, the ferrule, the cost, and never mind the chorus of voices from devotees to their particular makes and models—it’s a nearly paralyzing set of considerations.

Here’s where I’ve landed for now. Some days I use Musgrave Pencil Co.’s Pencil King in regal purple with a No. 1 lead; other days I use Musgrave’s No. 2 Tennessee Red, which is made from lovely eastern red cedar and varnished to reveal its distinct grain. Musgrave pencils are local to me, made in nearby Shelbyville, Tennessee, aka Pencil City, where they’ve been cranking out pencils since 1916.

Why shift between No. 1 and No. 2 pencils? As Steinbeck would say, some days are soft-lead days, others hard. The difference is I’m filing out my Full Focus Planner, not writing East of Eden, which incidentally took him about 300 pencils to finish.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

This is also why “plumbers” (who once worked with lead pipe) and “plumb lines” (from which hang lead weights) bear their peculiar names.

Medieval scribes did use actual lead to outline manuscript pages before applying ink and other pigments. Renaissance artists used silver for the same reason. While this metalpoint writing and drawing left a faint line on the page similar to graphite, it couldn’t be erased.

This is, by the way, the same Gessner who loved book indexes.

Apropos of almost nothing, U.S. President Franklin Pierce once owned a graphite mine.

The Thoreau grading system remains popular in the U.S. but is far from universal and lacks the nuance some users require, e.g., artists. Sometimes you’ll see pencils labeled HB, 2H, 9B, and so on. What do these mean and how do they compare? As Doug Martin explains, H refers to the lead’s relative hardness, and B (for black) to its relative opacity and softness. These exist on a range with 9H as hardest and 9B the darkest/softest. Here’s the full scale:

9H, 8H, 6H, 5H, 4H, 3H, 2H, H, F, HB, B, 2B, 3B, 4B, 5B, 6B, 7B, 8B, 9B

The Thoreau scale maps to the middle of the range. Working from softest to hardest, No. 1 corresponds to B, No. 2 to HB, No. 2½ to F, No. 3 to H, and No. 4 to 2H.

What about Blackwing, which uses its own classification? Working from softest to hardest, according to the Paper Mouse, Matte corresponds to 4B; Pearl is somewhere between 3B and 2B; the famous 602 is somewhere between B or HB (or No. 1 and 2 in the Thoreau system); and the Natural is between HB and H (No. 2 and 3).

Which do I like most? You’ll have to bounce back up to the main text to find the answer.

Compare Steinbeck to the thrifty Hemingway. As he wrote in A Moveable Feast about writing in a cafe, “The blue-backed notebooks, the two pencils and the pencil sharpener (a pocket knife was too wasteful), the marble-topped tables, the smell of cafe cremes, the smell of early morning sweeping out and mopping and luck were all you needed” (emphasis added). Apparently, Thornton Wilder once mentioned that Hemingway started each day with twenty pencils. Hemingway objected, “I don’t think I ever owned twenty pencils at one time. Wearing down seven number-two pencils is a good day’s work.”

Joel, you are a true renaissance man. Only you would add this off-topic post to your book reviews—and still keep my rapt attention. Pencils find themselves in my hands simply for woodworking, and they must stay short or get snagged on a thousand things as they protrude from my tool belt.

More than I ever wanted to know about pencils, yet once I'd peeked, I had to interrupt my own writing to read it all. AND make a comment!

I can't use a pencil myself. As one of the left-handed tribe, my moving hand smudges what I write and interrupts the fun. I use a cheap 1mm ball point, made in China, five for $4 Cdn at the Dollar Store. They're black, bold and dependable and I've grown fond of them. I have them scattered about and always available and I can give them away like a rich man if someone needs a pen.