Books: Indispensable When You’re Indisposed

The One Place You Really Need a Good Book—And Several to Try for Yourself

It’s no small mercy that one of life’s most elevated undertakings can occur during one of its most humbling. Yes, I refer to reading in the john. Stop blushing. You know you do it. Everyone does—especially if you’re a parent. I only wonder if we’re maximizing the experience.

Social media or a hastily snatched magazine are unworthy of such occasions. We require greater intentionality. As we all know, short and—ahem—digestible texts are usually best. Given that, some books are preferable to others in redeeming the time.

“Look for a boozy poet of the dark archway who,” says Roman poet Martial, “writes verses with rough charcoal or crumbling chalk which folks read when they s---” (Epigrams 12.61). Other translators try softening it, e.g., “poems which people read as they ease themselves.” But who are we kidding? The operative word here is cacantes. The other euphemism here is “dark archway” or “dark den.” Martial says nigri fornicis, which comes out more like “dingy brothel.”

Martial’s meaning is clear: There’s a kind of literature meant to be read in the bathroom and it’s naturally bad, written by bad people. But, my dear Martial, au contraire! The possibilities for great bathroom reading transcend the sewer into which all things tend. And with that dizzyingly hopeful thought in mind, here’s a handful of eminently suitable suggestions.

Montaigne’s Essays

Montaigne lived in the sixteenth century, but he could be your nextdoor neighbor—that is, if your next-door neighbor were wiser, funnier, better-read, and more self-deprecating. There is no human emotion Montaigne fails to touch or treat in his Essays, and he writes about almost every subject imaginable, including the one under consideration. “Both kings and philosophers defecate,” he says, “and ladies too.”

Within the span of a few dozen pages, he covers everything from war horses to ancient customs, prayer, aging, and (appropriately) smells. He addresses parental affection, will power, thumbs, changing your mind, names, sleep, sumptuary laws, cannibals, inconsistency, fear, sadness, solitude, friendship, even how we laugh and cry at the same things.

Montaigne tries warning off potential readers in the preface, saying it would be “unreasonable to spend your leisure” on the book. But it’s one of the few things about which he was entirely wrong. For his vast scope and deep insight, it’s both safe and fitting to say that Montaigne is one of the most fully human writers to ever take up the pen. And his wide reach means you’ll never be bored. No bathroom is complete without a copy of the Essays.

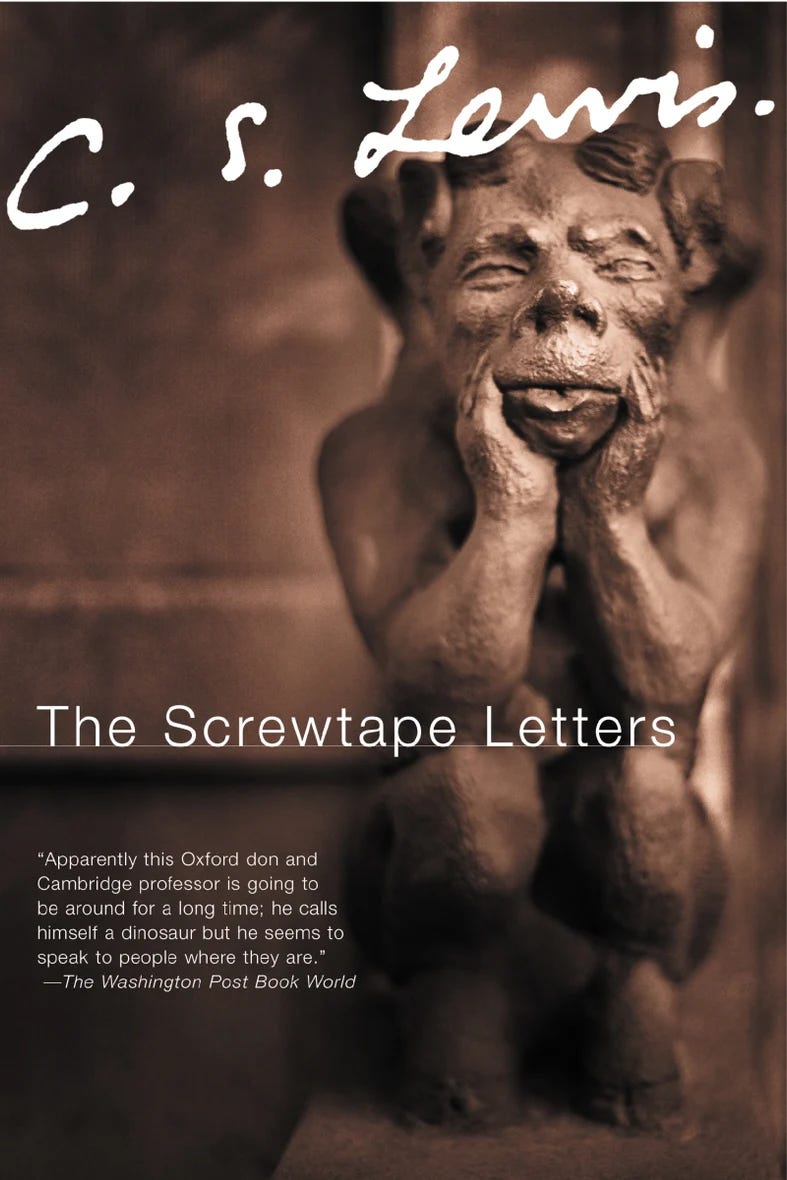

C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters

Even without the suggestive, squatting posture of the gargoyle on the cover of this particular edition, contemplating the advice of senior demon Screwtape to his nephew Wormwood while in the confines of the small room is eminently sensible.

Screwtape is one of those books that rewards many readings and can be picked up at any place and satisfy just about any mood. Lewis is sly, funny, perceptive, and on-point throughout. The discussions about the physicality of prayer or the dips and highs of living are, for instance, revelatory at the first reading and great reminders ever thereafter.

The Hebrew Psalms

If this one scandalizes you, you’re in great company. I once heard Fr. Tom Hopko mention a story about a monk who recited the psalter while on the toilet. His brothers, overhearing him, were horrified and dragged the offender before the abbot. To their chagrin, however, the elder vindicated the monk’s practice and his recitations continued.

It seems that qualms about prayer and the privy are the currency of the devil. Martin Luther tells the story of a monk who said his morning prayers while in the latrine. The devil appeared and scolded him. “What climbs up is for God,” answered the monk, “and what falls down is for you.” Bernard of Clairvaux had a similar exchange when the devil needled him about reciting psalms while relieving himself. “That which comes out of my mouth, I offer to God,” said the saint; “but that which I eject out of my belly, eat it!”

In these three cases, the prayerful have their material memorized. I’ve learned snippets and snatches of the psalms but require text for anything more. Thankfully, there are many wonderful psalters out there. Pictured above is the Holy Psalter from Saint Ignatius Orthodox Press. I also like the New Coverdale Psalter from Anglican Liturgy Press and the little leather-bound ESV psalter from Crossway.

Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary

Here’s another way to give the devil his due. Possibly the original spoof dictionary, Bierce started what became The Devil’s Dictionary in 1881 with definitions filed in a weekly paper. By 1911 it was a full-blown and riotous tome, made all the better by the posthumously published Enlarged Devil’s Dictionary in 1967 (my favorite edition).

I came across it when visiting a friend of one of my aunt’s. Upon my mentioning H.L. Mencken and P.J. O’Rourke, he retrieved a copy of Bierce and said in so many words, “You ain’t seen nothing yet.” There’s something amusing on every page. Here’s Bierce’s definition of cabbage: “A familiar kitchen-garden vegetable about as large and wise as a man’s head.” And belladonna: “In Italian a beautiful lady; in English a deadly poison. A striking example of the essential identity of the two tongues.”

John Gross’s Oxford Book of Essays

Besides being edited by a man with the right surname for the job, The Oxford Book of Essays rewards even the most casual of thumbings. With over a hundred essays by over a hundred authors, it’s hard to leave disappointed.

Gross’s wide-ranging collection features everyone from Francis Bacon to H.L. Mencken, Jonathan Swift, G.K. Chesterton, William Hazlitt, Mark Twain, John Henry Newman, and George Santayana. Perhaps best of all, you can find Ambrose Bierce’s hilarious and Facebook-timely essay, “Disintroductions.”

Humor me:

The devil is a citizen of every country, but only in our own are we in constant peril of an introduction to him. That is democracy. All men are equal; the devil is a man; therefore, the devil is equal. If that is not a good and sufficient syllogism I should be pleased to know what is the matter with it.

To write in riddles when one is not prophesying is too much trouble; what I am affirming is the horror of the characteristic American custom of promiscuous, unsought and unauthorized introductions.

You incautiously meet your friend Smith in the street; if you had been prudent you would have remained indoors. Your helplessness makes you desperate and you plunge into conversation with him, knowing entirely well the disaster that is in cold storage for you.

The expected occurs: another man comes along and is promptly halted by Smith and you are introduced! Now, you have not given to the Smith the right to enlarge your circle of acquaintance and select the addition himself; why did he do this thing? The person whom he has condemned you to shake hands with may be an admirable person, though there is a strong numerical presumption against it; but for all that the Smith knows he may be your bitterest enemy. The Smith has never thought of that. Or you may have evidence (independent of the fact of the introduction) that he is some kind of thief—there are one thousand and fifty kinds of thieves. But the Smith has never thought of that. In short, the Smith has never thought. In a Smithocracy all men, as aforesaid, being equal, all are equally agreeable to one another.

That is a logical extension of the Declaration of American Independence. If it is erroneous the assumption that a man will be pleasing to me because he is pleasing to another is erroneous too, and to introduce me to one that I have not asked nor consented to know is an invasion of my rights—a denial and limitation of my liberty to a voice in my own affairs. It is like determining what kind of clothing I shall wear, what books I shall read, or what my dinner shall be. . . . It is to be wished that some great social force, say a billionaire, would set up a system of disintroductions.

Can we get Elon on that next?

Finley Peter Dunne’s Mr. Dooley on Ivrything and Ivrybody

As you might guess from the language in the title, Mr. Dooley doesn’t speak the King’s English. Or the Queen’s English. Or anybody’s but his own. Dunne wrote the Mr. Dooley books a little more than a hundred years ago to feature the ramblings of an Irish—what else?—bartender named—what else?—Mr. Dooley. He’s also known as the philosopher; think Montaigne but with Bushmills.

Mr. Dooley holds forth on the news of his day (some of it is very dated, though still amusing) and subjects of timeless curiosity. A smattering of topics include books, anarchists, family reunions, keeping lent, history, swearing, vice, gratitude, and political reform movements—for example,

A man that’d expict to thrain lobsters to fly in a year is called a loonytic; but a man that thinks men can be tur-rned into angels be an iliction is called a rayformer an’ remains at large.

Honorable Mentions

Each of these books lends itself to moments of discovery and serendipity. And these by no means exhaust the possibilities—nowhere close. Scanning my shelves just now, I’ve pulled down a few others worth your attention, starting with two by the above-mentioned H.L. Mencken, both the delightful compilation, A Mencken Chrestomathy, and posthumous collection of Chicago Tribune essays, The Bathtub Hoax. Amusement awaits all who dabble within.

Then, in keeping with the undercurrent of devilry in these mentions, there’s The Untamed Tongue: A Dissenting Dictionary by psychiatric renegade Thomas Szasz—the cover of which fittingly features William Blake’s illustration of St. Michael binding Satan.

Along with these, I recommend two modern collections of aphorisms: Excellent Advice for Living by Kevin Kelly (reviewed here) and The Bed of Procrustes by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Both prompt useful thinking with every few lines. For that matter, so do the essays of George Orwell; it’s hard to go wrong with the big Everyman edition.

And finally, there’s no way to cap such a list without mentioning Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, particularly the complete collection of her crônicas, published in English under the title Too Much of Life. Is there a more lavatory-friendly literary genre than the crônica—essentially short, random, personal essays published in Brazilian newspapers on whatever happens to strike the writer’s fancy? Lispector wrote hers between 1967 and 1973 and treats every subject imaginable.

“I’ve been spending a lot of time with myself recently and was surprised to discover that being me is bearable, sometimes even pleasant,” she wrote in 1972. “Well, not always.”

I do hope to say more about Lispector’s collection in the future. It is enough to mention here that if Montaigne were Brazilian and female, he might have approached her genius. They certainly would have loved each other’s company. You will too. It’s hard to think of a more edifying way to pass, er, the time.

Thanks for reading and shaping the community here at Miller’s Book Review 📚. If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

If memory serves, most Orthodox publishers take a dim view of hauling the Psalter into the shitter.

The bathroom, toilet, and by any other name - it's actually a sacred place to cleanse body and soul, crying on the floor or under the shower, smoking in secret (maybe not any more?), making private calls, getting away from the family arguments or a violent partner, a place you can be raw and truthful and swear at life and people who are making it difficult for you. We should have bookshelves and libraries waiting for us, welcoming us. Thanks for the post and the recommendations.