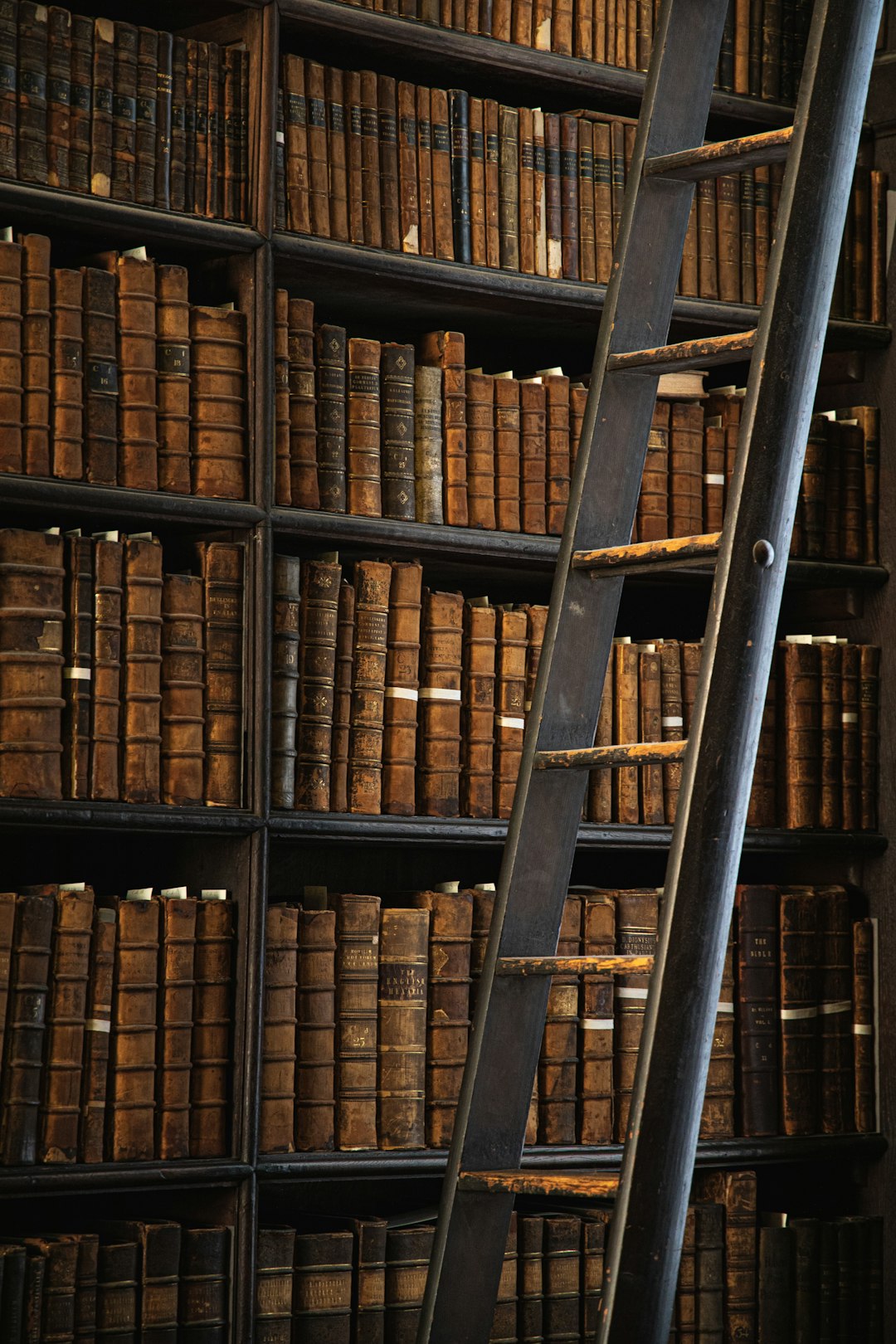

Bookish Diversions: Why Read Old Books?

Michael Dirda, C. S. Lewis, the Relevance of Homer, John Donne, Clearing Chaucer’s Name, More

¶ Old books or new? Looking over my reading from the past year, I noticed a large percentage of newer books, titles published within the last couple of years. There’s nothing wrong with this. In fact, Washington Post book critic Michael Dirda cites Jean-Paul Sartre’s opinion in What Is Literature? to argue that writers—and readers—ought to be concerned with what’s happening now.

But it’s ironic to mention a book published in 1947 when arguing we should focus on the present, no? Dirda is having some fun here.

While noting the value of modern books, Dirda recommends adding old books to the mix. He offers several reasons. “The foundations of learning, I quickly realized, were nearly all located in the past,” he writes of his own education. “Time had done its winnowing, and what remained were the works and ideas that shaped human civilization.” These old books exert creative power, forming strands of the ideational DNA used by modern authors to spin new yarns. “In the arts, especially,” he says, “education consists of seeing how deeply the past informs the present.”

Sometimes we might be offended by what we find thumbing through the classics. Dirda notes the casual prejudice and bigotry one might encounter in old books. “No matter,” he says. “Read them anyway. Recognizing bigotry and racism doesn’t mean you condone them. What matters is acquiring knowledge, broadening mental horizons, viewing the world through eyes other than your own.”

Old books offer us the perspective of a different vantage point, one removed from our own moment. We can correct what we find in them, and they can sometimes correct what they find in us. C. S. Lewis wrote about that feature of old literature when introducing a new translation of Athanasius’s On the Incarnation, originally written in the fourth century. “Every age has its own outlook,” he says.

It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books. All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook—even those, like myself, who seem most opposed to it. Nothing strikes me more when I read the controversies of past ages than the fact that both sides were usually assuming without question a good deal which we should now absolutely deny. They thought that they were as completely opposed as two sides could be, but in fact they were all the time secretly united—united with each other and against earlier and later ages—by a great mass of common assumptions.1

We can detour here to another book by Lewis, The Discarded Image, where he underscores this tendency in late classical culture among pagans and Christians. “They were in some ways far more like each other than was like a modern man,” he says. They “had the same education, read the same poets, learned the same rhetoric.” Sharing the same culture and formation, ancient pagans and Christians tended to share much of the same worldview. Lewis notes it’s sometimes difficult to tell if an ancient author of this or that book was pagan or Christian so close were their perspectives.2

And the same is roughly true today. We are shaped in a world of Western, liberal values influenced by deep undercurrents of Christian thought and practice. Whatever our disagreements with our neighbors, we share more than we realize and are usually blind to the commonalities.

Ideas circulate in certain times and places. Ages and decades, though not sealed off, can nonetheless act like echo chambers in which certain views and philosophies reverberate more loudly than others. We fix on them and find ourselves living in response to them whatever we think or assume about them. Books can either reinforce the bubble—or pierce it.

By focusing on prevailing messages to the exclusion of others, we become blind to—and forgetful of—other perspectives. Excluding old books can reinforce this dynamic. “None of us can fully escape this blindness,” says Lewis, “but we shall certainly increase it, and weaken our guard against it, if we read only modern books. Where they are true they will give us truths which we half knew already. Where they are false they will aggravate the error with which we are already dangerously ill.”

On the other hand, interspersing modern reading with classics can expose us to ideas that run counter to the prevailing culture, sometimes helpfully so. As such, Lewis suggests keeping “the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds. . . .” How? “By reading old books.”

Of course, old does not equate to good, right, or true. People were just as prone to faults and foibles in the past as we are today. But, as Lewis says, authors of prior ages were prone to different errors than our own and also unlikely to affirm us in ours. In a sense, it comes down to crowdsourcing: “Two heads are better than one,” says Lewis, “not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction.”3

It’s the very distance from our own times and perspectives, along with their particular blinders and biases, that make old books valuable. We don’t have to fear the follies and failings of old books; we’ll spot them easily enough. The value comes when the expose faults in us.

But, as Dirda goes on to explain, there’s more value to be had from old books than perspective and corrective. They can also be fun and refreshing, especially in heavy or difficult seasons. “The great books are great because they speak to us, generation after generation,” he says.

They are things of beauty, joys forever—most of the time. . . . The books of the past, besides adding to our understanding, offer something we also need: repose, refreshment and renewal. They help us keep going through dark times, they lift our spirits, they comfort us.

I’ve decided to counterbalance my inadvertent focus on newer books this coming year by reading more classic fiction. You can find out about that here and recommend books you think I should add to my 2023 classic fiction list. Check out the comments; readers have already suggested some real winners. What are your recommendations?

¶ Judging the past

There is only one standard by which any epoch can be fairly judged: in view of its own peculiar circumstances, to what extent did it allow for the development of human dignity?

—Romano Guardini4

¶ Why read Homer? Andrew Kern argues the Iliad and Odyssey, when read together, provide a theater for personal reflection and self-evaluation. Homer “moves the audience toward awareness of their own thoughts and motives,” he says. The two epics “provide space for audience members, both then and now, to wrestle with what is good, meaningful, and beautiful in the varying circumstances of life.”

¶ #MeToo #Nevermind. The legacy of Geoffrey Chaucer, author of The Canterbury Tales, drifted under a dark cloud about 150 years ago. In 1873 a scrap of legal paperwork emerged suggesting he’d raped a baker’s daughter named Cecily Chaumpaigne. Now, however, two scholars have exonerated the poet, showing the case has not only been misunderstood, but that Chaucer and Chaumpaigne were actually both defendants in a labor dispute. It’s a wild story and one that reminds us the value that scholarship offers.

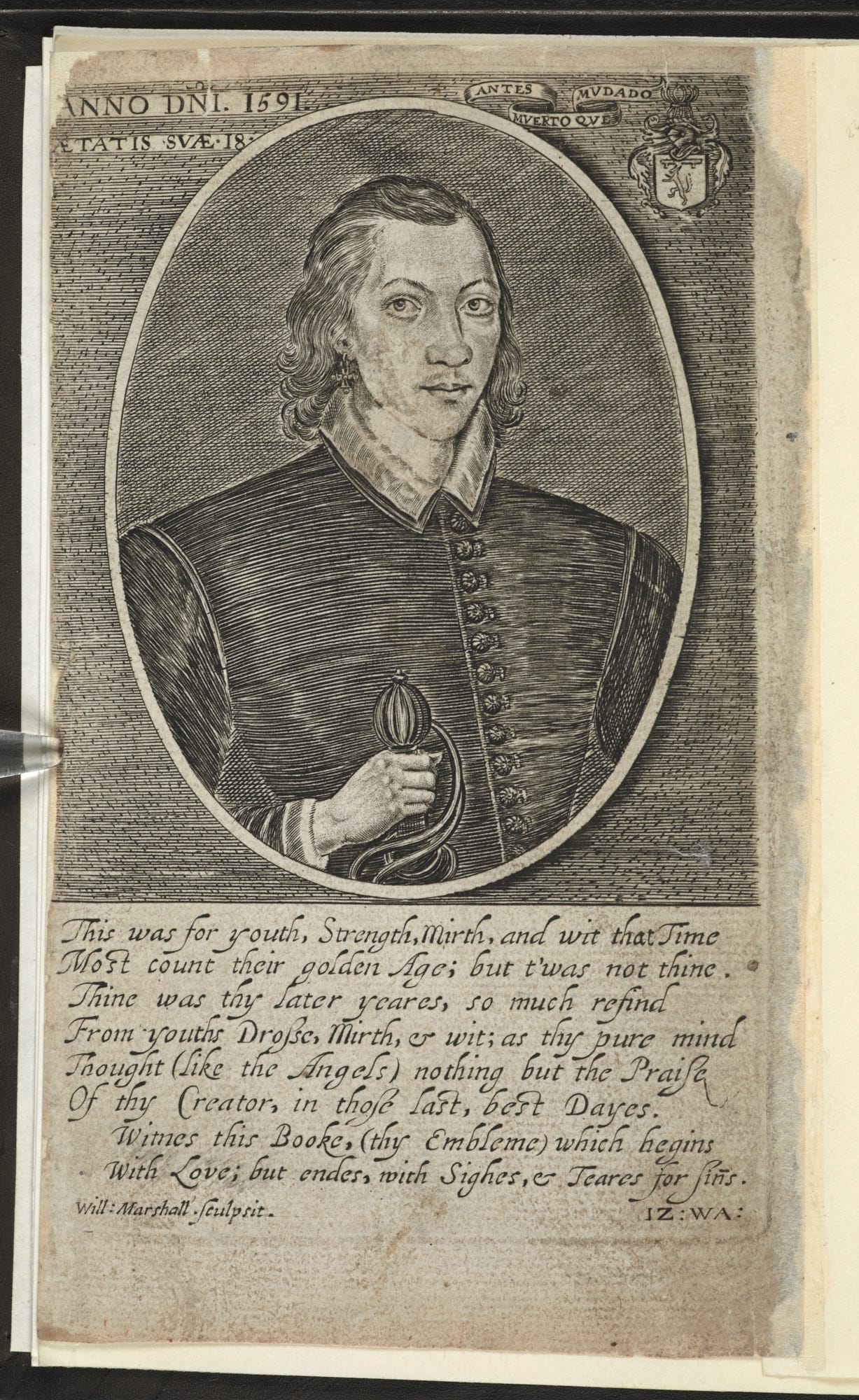

¶ John Donne was never done. Writing at

, James Broughel highlights a new biography of the mercurial poet and eventual preacher. “Donne was a complicated figure. Today he might be best known as the author of the words ‘no man is an island unto himself,’ or the expression ‘for whom the bell tolls,’” says Broughel, but Donne was also the subject of scandal and a trickster, restless, and never quite finished evolving as a person.

Modern Library has a beautiful and handy edition of Donne’s poetry and prose, a treasury of ideas and expressions that never ceases to surprise.

¶ Modern minds in collision. The present is the product of the past, and our current conception of the self stems in part from a cluster of intellectuals knocking around a German university town in the late 18th and early 19th centuries: “The philosophy of these first Romantics was and remains knotty; but in their emphasis on freedom and the self, they ushered in a new world of feeling and thought.”

¶ What about intimidating classics? I sometimes joke that I’ve started reading The Brothers Karamazov more times than some people quit smoking. It’s one of those books I’ve felt I ought to read but just can’t seem to turn past the hundredth page. This takes me back to Dirda’s essay. Yes, reading the classics is important but, he asks,

Does that mean you should devote your evenings to arguing with Plato, working your way through Dante and learning how to live from Montaigne? Being an idealist, I think you should, though certain classics—Samuel Johnson’s moral essays, George Eliot’s “Middlemarch”—are best appreciated in middle age, when they will pierce you to the marrow. Still, literature’s Himalayan peaks can be daunting. As the Victorian classicist Benjamin Jowett once said, “We have sought truth, and sometimes perhaps found it. But have we had any fun?” In reading as in life, fun does matter.

So, yes, struggle with the challenging books. But find some classics that are fun. Engaging with classic literature has some inherent difficulties; the distance posed by culture, language, and literary form can be tough to bridge. These difficulties are not insurmountable, however, and sometimes they exist in our expectations alone. Dostoevsky may have stumped me, but I actually find Montaigne hilarious at times and always interesting. Once you get started you discover some paths easier to walk than you first assumed; those intimidating Himalayan peaks reduce to gentle hills.

¶ Used, abused, and loved. Sometimes the more we love a book the more raggedy it gets. “As I look at my bookcase these days, I come to the conclusion that the more damaged books are those I’ve read the most,” says Carina Pereira, “those I’ve spent more time with, those which have travelled with me back and forth even when I lacked time to read. Those battered copies now give me comfort rather than distress me.”

¶ Also, a reminder: If you want to suggest any classic novels for my reading list in 2023, leave your recommendations here. I’ll be sharing my reviews in just one place—right here.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe.

C. S. Lewis, God in the Dock (Eerdmans, 1972), 202.

C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image (Cambridge University Press, 1962), 45–46.

Lewis, God in the Dock, 202.

Romano Guardini, The End of the Modern World (ISI Books, 1998), 22–23.

I thought “Man, this link better go to Dominion.”

My wife is getting a Masters Degree in classical education and it’s a blast to see that all ideas are as old as time. Nothing new under the sun is a pretty old thought. I feel like we live in a NOW obsessed culture to our thought detriment.

Excellent! I’m keeping this to share with others about the value of a challenging read in this age of short attention span. I try to alternate something new with a classic.

We are over published in our times! It’s hard to find the gems. Thanks for being a voice of wise guidance.