Bookish Diversions: All the Presidents’ Books

Washington’s Radicals and Rogues, Kennedy’s Cuba Advisor, Tricky Dick, Obama’s Lists, Trump’s Favs, More

¶ Presidential libraries. Like pinkeye, toe fungus, and herpes, politics is something I do my darnedest to avoid. “Democracy is the theory,” said H.L. Mencken, “that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” Point taken, concussion sustained.

But it seems impossible to separate an interest in books from at least an occasional nod toward America’s diverse cast of presidents. It goes back to the beginning.

¶ George Washington, reader. We’re inclined to think of founders like John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison as particularly bookish. The lives and legends of the second, third, and fourth U.S. presidents provide plenty of reasons to think so.

Jefferson found himself under mountains of debt amassing his personal library and had to sell the whole lot, thousands of volumes, to Congress to quiet his creditors—a sale that laid the foundation for the Library of Congress. For his part, Madison signed the bill that authorized the purchase. In my upcoming book, The Idea Machine (out this November!), I devote an entire chapter to Jefferson and Madison’s mutually beneficial book craze, using their letters and papers to show how they built and employed their own libraries.

But it wasn’t just those luminaries. When George Washington returned like Cincinnatus to the plow, he also returned to a decently stocked personal library at Mount Vernon. Kevin J. Hayes explores Washington’s love and use of books in his study, George Washington: A Life in Books. His affection for books began in childhood when his mother Mary read to her children such riveting classics as Matthew Hale’s Contemplations Moral and Divine but the appeal lasted through the rest of his life.

Hayes points to, for instance, the books on agriculture Washington acquired as a planter—including rare volumes, such as Duhamel du Monceau’s Practical Treatise on Husbandry, dotted with Washington’s notes and marginalia, helping him to apply the advice to his own practice.

Washington’s collection ranged far beyond the farmyard, however. He held copies of John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon’s radical Whig works, The Independent Whig and Cato’s Letters. He possessed Tobias Smollett’s multivolume Complete History of England, Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin’s History of the Bucaniers of America, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and a broken set of Alexander Pope’s Poetical Works, including his “Essay on Man,” plus standbys like Homer and Aesop and less reputable fare, such as Theophilus Lucas’s Memoirs of the Lives, Intrigues, and Comical Adventures of the Most Famous Gamesters and Celebrated Sharpers. So, basically radicals and rogues, interspersed with the old reliables—exactly what you’d hope America’s first president would enjoy of an evening.

¶ Policy by the pages. One doesn’t have to look long or earnestly for references to the role books and authors play in the lives of politicians. Just browse any magazine about public affairs and the references sneak up on you, as with this tidbit from a James Parker piece on Ian Fleming:

Fame as the creator of James Bond, in combination with his old elite connections, would project Fleming back into the center of events. Senator John F. Kennedy, a huge fan, sought his counsel about Cuba.

Explains a lot.1

Back in 2011, Tevi Troy examined the literary legacies of presidents in the pages of the Washington Post. He looked at the bookish habits of founding presidents, such as Jefferson and Adams, but he also flipped the calendar to the present, including such notable chief executive readers as Teddy Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Jack Kennedy, all the way down to Barack Obama.

Partisans will bicker over the result, but Kennedy soon graduated from spy thrillers. In the White House, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. suggested weightier books for the president to read, and Michael Harrington’s The Other America galvanized Kennedy’s decision to create federal programs to combat poverty. Kennedy’s speechwriter and adviser Ted Sorenson read Dwight McDonald’s lengthy review in the New Yorker and began hyping the book. Copies of The Other America started buzzing around the office, along with its possible policy implications.

Moved by Harrington’s work—and possibly to defray liberal ill will over his tax cuts—Kennedy pushed his team to examine the issue. But with the president gunned down in Dealey Plaza just days later, the eventual War on Poverty fell to his successor, Lyndon Johnson (himself motivated by yet another book, The Rich Nations and the Poor Nations by economist Barbara Ward).

Books regularly steer their readers into contentious and complicated waters, as President Nixon discovered—arguably too late.

¶ “I am not a book!” Nixon may not have a reputation as a reader; he’s famous for other reasons. But he was a dedicated bookworm. “I am not educated,” he told his staff during his farewell address in 1974, “but I do read books.” Lots of them, as it happens.

Citing the presidents memoirs, Troy mentions that Nixon “read Tolstoy extensively in his youth and even called himself as a ‘Tolstoyan,’” though some might regard him more like a character from Dostoevsky. We rarely live up to our aspirations, and sometimes, of course, we inadvertently live down to them.

Some years ago, journalist Andrew Ferguson undertook the fascinating project of reading through Nixon’s marginalia, annotations left in the books he owned. Historians have probed every nook and cranny of Nixon’s life for fodder, but Ferguson realized they’d ignored one trove of possible insight. “From what I could tell,” he says,

no one had yet mined this remarkably varied collection, more than 2,000 books filling roughly 160 boxes stored in a vault beneath the presidential museum. Taken together, they reflect the broad range of Nixon’s intellectual curiosity—an underappreciated quality of his highly active mind.

Sure enough, Ferguson found a heavily inked biography of Tolstoy in the collection, along with other surprises. Nixon underlined as he read. “Marking up books was . . . a way of slowing himself down and attending to what he read,” says Ferguson. “He was not a notably fast reader, by his own account, but his powers of concentration and memorization were considerable. Going at a book physically was a way of absorbing it mentally.”

Books whose marks reveal extensive engagement include a Charles de Gaulle treatise on statesmanship (not surprising) and “a deep dive into the historiography of Japanese art” (more surprising). “Several fat volumes of The Story of Civilization, Will and Ariel Durant’s mid-century monument to middlebrow history, display evidence of attentive reading and rereading,” reports Ferguson.

Unlike John Adams, who bickered with his books in the margins—for instance, filling his copy of Mary Wollstonecraft‘s An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution with 10,000 words of his own—Nixon didn’t argue with authors. Instead, says, Ferguson,

he restricted his marginalia almost exclusively to underlining sentences or making other subverbal marks on the page—boxes and brackets and circles. You get the idea that he knew what he wanted from a book and went searching for it, and when he found what he wanted, he pinned it to the page with his pen (seldom, from what I’ve seen, a pencil).

Why one mark and not another? No one can say. “A line, a check mark, a circle—why Nixon deployed one notation and not another for any given passage is a question as unanswerable as ‘Why didn’t he burn the tapes?’”

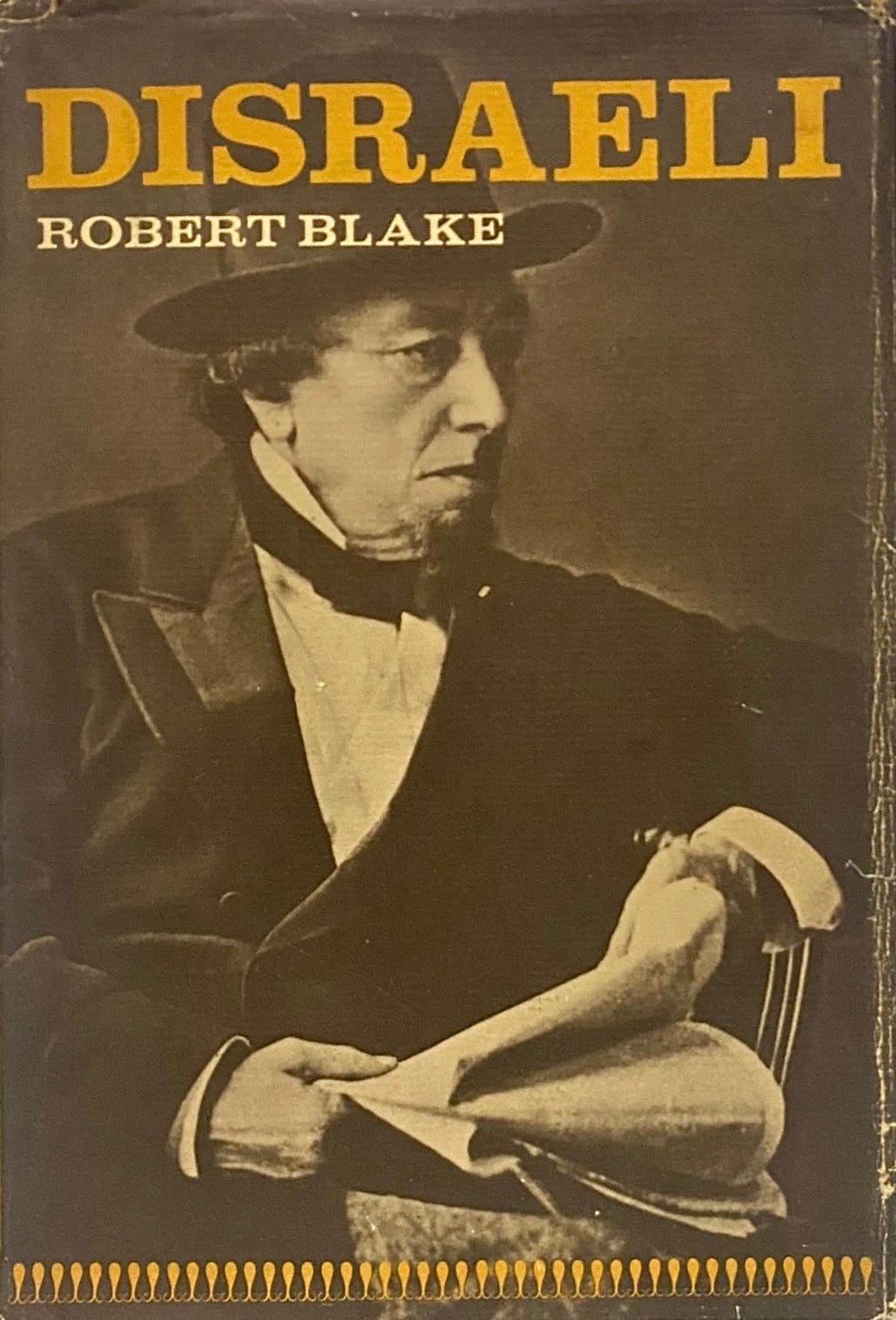

Like all of us perhaps, Nixon tended to look for himself in his reading. One particular example from Ferguson’s adventures in the boxes stands out. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a future U.S. senator and Nixon’s top domestic policy advisor, gave his boss a copy of Robert Blake’s 1966 biography Disraeli about one of Britain’s most remembered prime ministers from the Victorian era, Benjamin Disraeli.

Nixon devoured it and deeply identified with its subject, labeling himself a “Disraeli conservative.” It’s easy to see why, as Ferguson’s reading of the president’s marginalia attests. While Nixon publicly claimed the label for policy reasons, the deeper reason seems more personal.

Disraeli’s contemporaries viewed him as an outsider. Nixon felt that in his bones. When Blake’s biography discusses the disdain of Disraeli’s peers, Nixon’s pen went to work, bracketing and underling entire passages. “Men of genius operating in a parliamentary democracy,” wrote Blake, “inspired a great deal of dislike and no small degree of distrust among the bustling mediocrities who form the majority of mankind.”

Nixon both bracketed and underlined that bit. Says Ferguson,

The antagonism of the elites was not the determining fact of Disraeli’s career, but both biographer and subject perceived its profound effects, and so did the man reading about it 90 years after Disraeli’s death. As president, Nixon felt himself similarly situated: the political leader of an imperial nation, highly skilled, aching for greatness, yet in permanent estrangement from the most powerful figures of the politics and culture that surrounded him, nearly all of whom he judged, as Disraeli had, “bustling mediocrities.”

Nixon acted on what he read as well, going so far as to sack his entire cabinet after his rousing 1972 reelection because he feared his staff would grow complacent and ineffective. Disraeli warned of “exhausted volcanoes” and his biographer noted the danger of an “energetic administration“ beset by “accidents, scandals and blunders.” Nixon underlined it all and asked the whole lot to resign.

Books can remedy our character defects; they can also amplify them. “A book is like a mirror,” said German scientist and satirist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. “If a donkey looks in, you can’t expect an apostle to look out.” In trying to avoid “accidents, scandals and blunders,” Nixon wandered into them like a figure from Greek myth.

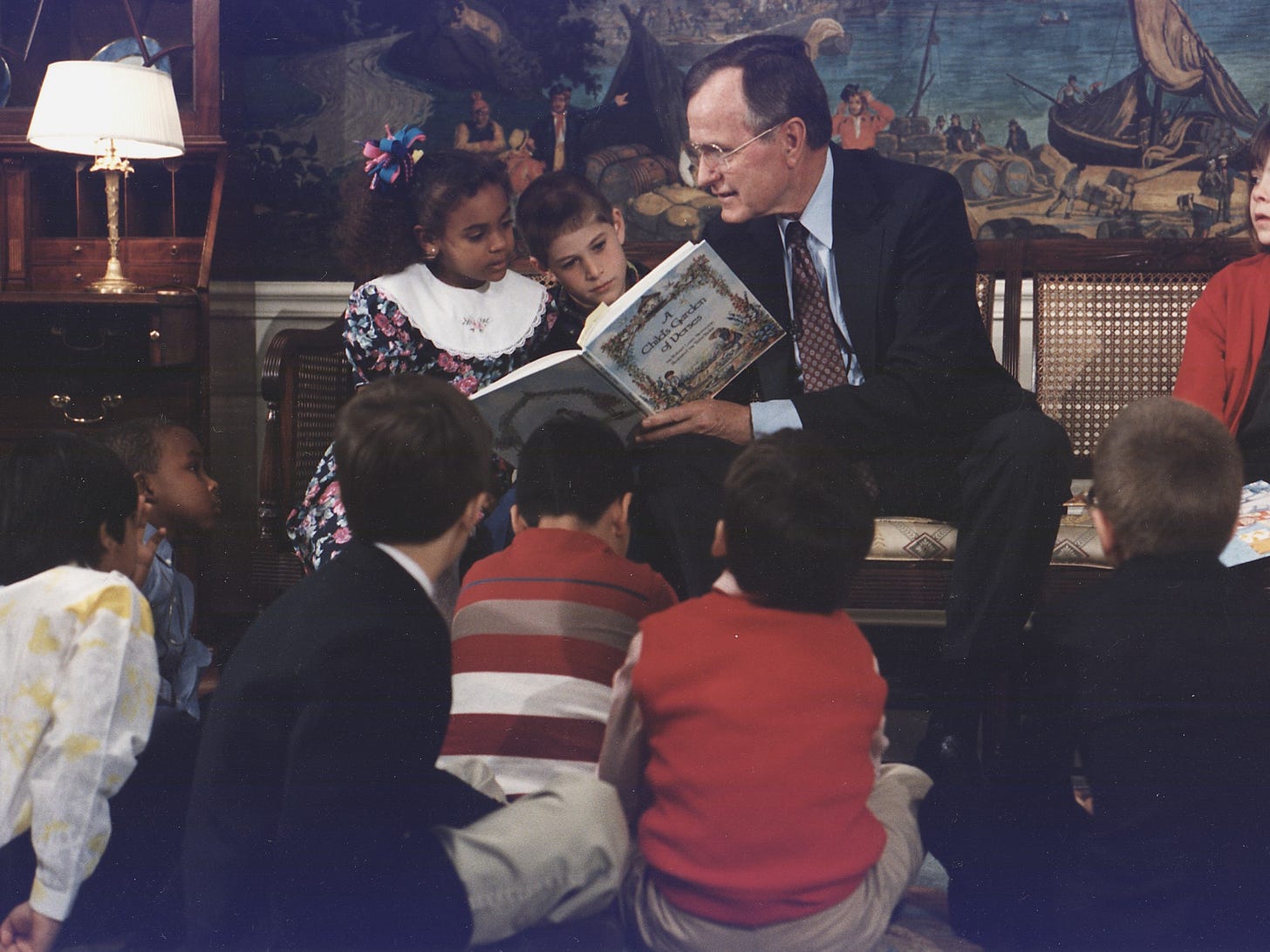

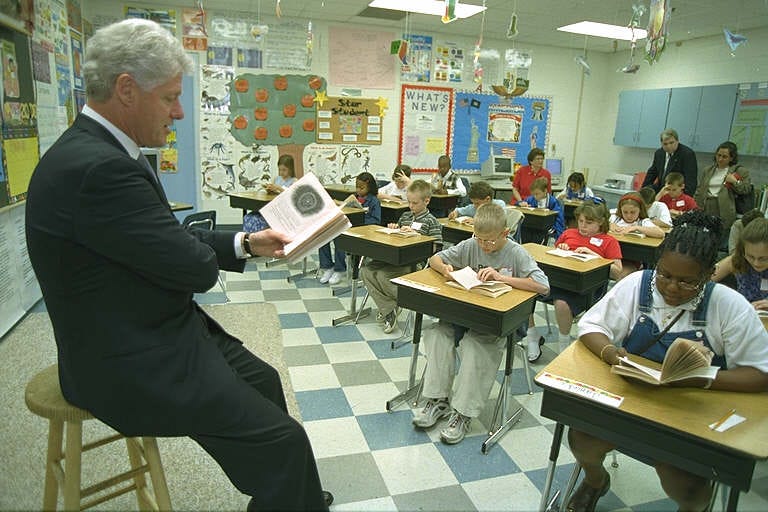

¶ Advocates for literacy. For better or worse (often worse), presidents are figureheads whose moves and moods influence the nation. As such, our chief executives have been roped into playing the role of reading advocate to the country’s children.

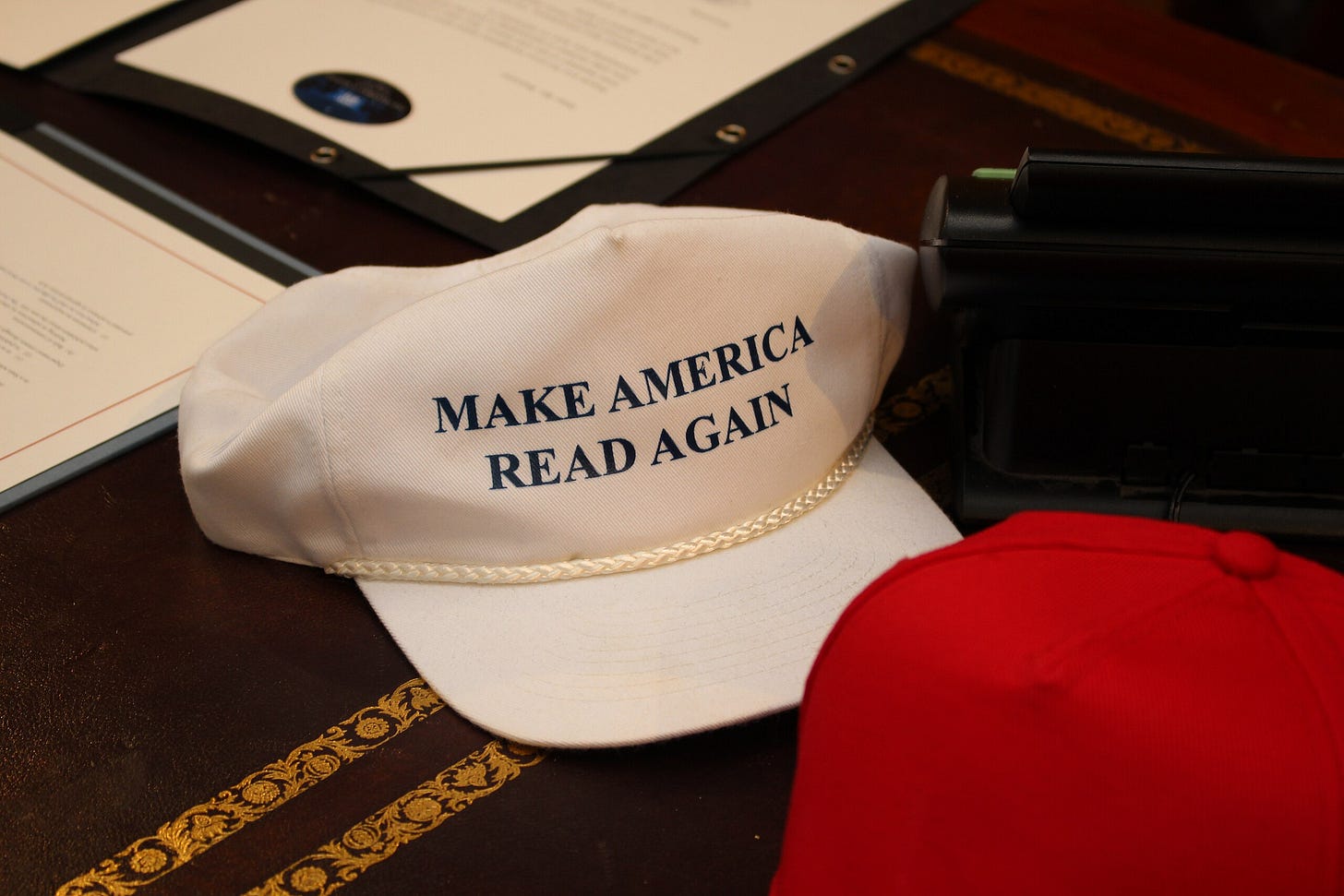

President Barack Obama leaned into the role. He made much of reading before taking office, made recommended reading lists during his time in office, and has kept it up in his post-presidency. Though less readerly than many others, President Trump also has a list of favorite books and indirectly gave us a wonderful hat.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

It’s worth mentioning that Kennedy’s rumored mistress, actress Marilyn Monroe, was a serious reader, and his widow, Jackie Onassis, went on to become a celebrated literary editor, as detailed in a couple of books about the latter part of her life.

In the early 2000s, I wrote a New York Times economics column in rotation with three other columnists, including the Princeton economist Alan Krueger. One of his columns opened with a story that prompted another economist friend of mine to comment that Krueger was always lucky:

"Not long ago, I asked my research assistant, Melissa Clark, to track down a passage from ''The Wealth of Nations'' by Adam Smith. Although I expected her to consult the modern edition, she instead requested the original 1776 edition from Princeton's Rare Book Library. The librarian accidentally gave her the fifth edition, published in 1789, and therein she discovered a remarkable signature: George Washington."

https://www.nytimes.com/2001/08/16/business/economic-scene-the-many-faces-of-adam-smith-rediscovering-the-wealth-of-nations.html?unlocked_article_code=1.d08.JZTs.l9owfM6tUM9q&smid=url-share

I have a similar aversion to politics and I loved this post! It's always fun peeking into other people's reading lists. And as always, your writing is so enjoyable to read.