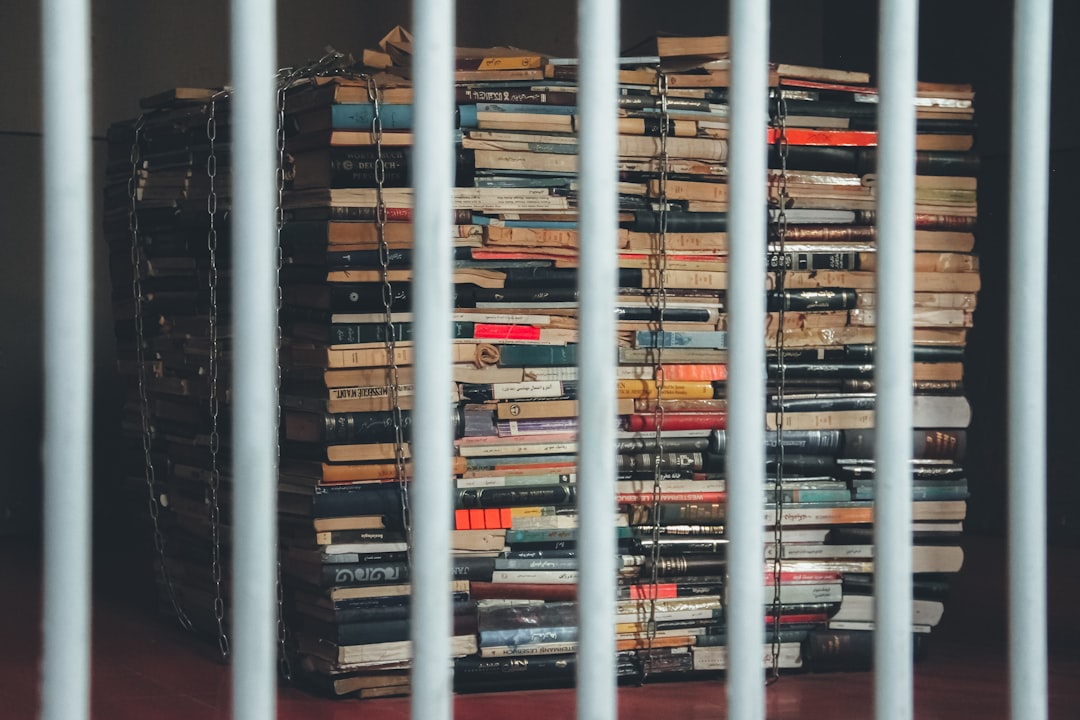

Bookish Diversions: Reading in Jail

Books Behind Bars, Blackout Poetry, Smuggling Books, Seditious Chinese Children’s Books, Gutenberg Updated, More

¶ Books behind bars. As a teenager Reginald Dwayne Betts carjacked someone, got arrested, confessed, and was sentenced to prison. “The first morning I woke up in a cell,” he remembered in a piece for the New York Times, “I was 16 years old and had braces and colorful bands covering my teeth. My voice cracked when I spoke. I was 5-foot-5 and barely weighed more than a sack of potatoes.” Despite his youth, he quickly adapted to prison life. “Before my 18th birthday, I’d scuffle in prison cells, be counseled to stab a man (I declined) and get tossed into solitary confinement five times.”

What kept him from being swallowed whole? “The memory that endures is the moment a prisoner whose name I’ve never known slid Dudley Randall’s ‘The Black Poets’ under my cell door in the hole.” As he said in an interview with the Paris Review,

Books fundamentally changed my life, and I got books in prison in all kind of ways—some legit, some not legit. I sold people tobacco at exorbitant rates for a couple of years. I’m talking about a $6 bag of tobacco I would sell for $130, which is not a nice thing to do. That s— funded my poetic education, you know?

Betts joins a long line of convicts whose lives have been bettered—in some cases transformed—by books. Now over forty and free, Betts works as a lawyer, prison-reform advocate, poet, and social entrepreneur. And he’s trying to help more people behind bars connect with the literature that might open their eyes and redirect their trajectories. “Books become essential when you want to imagine a new life for yourself,” says the website of Freedom Reads, the inspiring organization Betts founded to get books into correction facilities.

He’s had a remarkable impact so far, placing more than seventy-seven thousand books in prisons across forty different states.

¶ Case the joint. Where do these books go when they arrive? Most prisons are not equipped to display the books they’re gifted and so Betts’ team has designed special bookcases to display the collections. Size, shape, materials, the ability to house books on both sides of the installation—all factors were considered. Talking with Russ Roberts on EconTalk recently, Betts explained all that went into the design; it’s a fascinating digression and warrants a listen.

¶ Free form. Prison had a direct impact on the design of Betts’ most recent coauthored book of poetry, Redaction (poems by Betts and illustrations by artist Titus Kaphar). It had to be softcover, for instance, because prisons don’t permit hardcover books. But the overall design, which features unique inks, paper stocks, and production methods is unique enough to warrant attention from Fast Company for its innovative approach. If you’re into book design, I bet you’ll find it fascinating.

¶ Blackout. The art and poems in the book began as an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. Betts used blackout poetry, in which a page of text has lines selectively blacked out to fashion a poem from the leftover text still visible. It’s essentially using redaction to change one message into another—hence the title of the book. Here’s Betts explaining the process and his reason for using this approach:

I’m trying to find ways to connect my identity as a lawyer with my identity as a poet. I’m on the board of the Civil Rights Corps, which deals with money bail. They are specifically trying to challenge the fact that many states incarcerate people and leave them incarcerated just because they can’t pay their bail or because they owe fines for traffic tickets or things like that, citations.

But nobody can understand these court documents. I mean, you get sixty to seventy pages. It’s like reading a novella, and you don’t want to really read a novella that’s talking about things like jurisdiction. But what I thought about was this poetry-ness, and if we can find the poetry. Instead of thinking that redaction is a tool to get rid of and hide what is most sensitive, what if we thought about it as a tool to remove the superfluous? What if I tried to find the rhythm, the poetry, the character, the story, the person? If I allowed the document to actually be a voice of the person writing it? That’s what I attempted to do.

For me, this says a couple of things. It represents the attempt of the state to physically remove you, but then it also represents the attempt of people to reassert their existence. Those two things get to exist as one. In the same way that these two things are happening, there’s this fight against erasure. I think that’s what the poems end up mimicking. Even though the portraits on the cover represent that erasure, they also represent the existence of something underneath. It’s pushing back against that.

Here’s more of Betts and Kaphar talking about the project. And here’s a history of blackout poetry you might find helpful. Along with that, try this video from multimedia artist and writer Austin Kleon: “How to Make a Newspaper Blackout Poem.”

¶ Book smugglers. In the nineteenth century, Russia ruled the little nation of Lithuania. After a failed rebellion, the larger state tried several repressive measures to quell future attempts at autonomy. One method? They banned the production of books in the Lithuanian language printed in Roman characters; the Russians wanted the Lithuanians to begin only using books published in Cyrillic characters and printed by the Russian government. Reasonably enough, the Lithuanians took this as an attempt to wipe out their culture. Their response? Print books out of the country and smuggle them back in. From Atlas Obscura:

Thus appeared the first of the knygnešiai—or book-carriers. . . . Initially, the knygnešiai worked alone. They carried books in sacks or covered wagons, delivering them to stations set up throughout Lithuania. They performed most of their operations at night, when the fewest guards were stationed along the border. Winter months—especially during blizzards—were popular crossing times.

Lithuanians went to great lengths to conceal their illegal books. The Forty Years of Darkness by Juozas Vaišnora reports of female smugglers who dressed as beggars and hid books in sacks of cheese, eggs, or bread. Some even strapped tool belts to their waists and pretended to be craftsmen, disguising newspapers under their thick clothes.

Bishop Motiejus Valančius . . . organized the first large-scale attempt to smuggle books across the Lithuanian border. In a bid to publish more prayer books, he sent money to neighboring Prussia to construct a printing press there. Beginning in 1867, he tasked a number of priests with bringing the books back into Lithuania and distributing them to locals.

The book smugglers succeeded and are remembered to this day with a special commemoration every March.

¶ Seditious children’s books. Authorities in Hong Kong recently arrested two men for possessing copies of children’s books deemed “seditious.” As reported in the Guardian, a Chinese-language paper said the publications were sent from Britain to Hong Kong and included several copies of illustrated children’s books in a series that portrayed Hongkongers during the 2019 unrest as sheep trying to defend their village from wolves, an apparent reference to the mainland Chinese authorities.” Can’t have that now, can we?

¶ Losing proposition: fighting erasure with erasure. I’ve criticized Russia for—among its many inexcusable aggressions—targeting Ukrainian cultural sites, especially libraries. (See the article below.) But Ukraine has followed suit, purging 19 million Russian and Ukrainian-language, Soviet-era books from its libraries. Removing books from circulation doesn’t change history, and makes it harder for people to understand their present.

¶ Digital book smugglers. Ideas Beyond Borders represents one modern-day version of the Lithuanian book smugglers. They translate articles and books of science, free speech, and women’s rights for regions in which those pursuits are undervalued and even verboten. They’ve distributed 75,000 ebooks so far, and their efforts have single-handedly doubled the size of Wikipedia Arabic. They have a fantastic Substack,

, and here’s a worthwhile interview with founders Faisal Saeed Al Mutar and Melissa Chen.¶ Gutenberg, updated. Ideas Beyond Borders depends on ebook technology. The origins of ebooks go back to the earliest days of the Internet and the first glimmer of Project Gutenberg. Here’s a short but fascinating history of the effort to digitally disseminate public-domain texts.

¶ Betts on it. Coming back to Dwayne Betts, I encourage you to listen or watch the EconTalk episode from January.

¶ If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. Thanks!

¶ Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading.

Speaking of the Lithuanian book smugglers, there's an excellent middle grade historical fiction novel about them by Jennifer Nielsen called "Words on Fire."

Powerful stuff. Thank you. You would enjoy Redeeming Justice by Jarrett Adams as well.