Book Borrowing, Book Stealing: What’s the Difference?

The Morals of George Orwell’s Library Math: Do the Books We’ve Borrowed and Lent Even out in the End?

Pushkin is to Russian literature what Shakespeare is to English, and first editions of his books have been disappearing across Europe. A sophisticated group of forgers and thieves have been consulting rare copies in libraries and replacing the originals with intricately produced fakes.

“Since 2022, more than 170 books valued at more than $2.6 million . . . have vanished,” reports the New York Times. State and university libraries in Germany, France, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland have all suffered losses. “The University of Warsaw library was hardest hit, with 78 books gone.”

But sometimes book theft is less egregious, less obvious. For instance, what about that novel you borrowed from me nine years ago and is still somewhere on your shelves? And don’t I still owe you that essay collection, the one by what’s-his-name?

Orwell’s Book Math

Addressing the cost of books compared to other expenses and pastimes, George Orwell once tallied the titles on his shelves. Counting “only those books which I have acquired voluntarily, or else would have acquired voluntarily, and which I intend to keep,” he arrived at 442 in all.

Most of those, 251, Orwell had purchased himself. Another large slice, 143, he received as complementary copies for reviews, presumably from publishers or authors. And the rest? He divided the stragglers into three smaller categories:

“Given to me or bought with book tokens”: 33

“Borrowed and not returned”: 10

“Temporarily on loan”: 5

Why include borrowed books in the total of books he owned? “Book-giving, book-borrowing and book-stealing more or less even out,” Orwell explained, a claim detailed with nearly unimpeachable logic: “I possess books that do not strictly speaking belong to me, but many other people also have books of mine: so that the books I have not paid for can be taken as balancing others which I have paid for but no longer possess.”

Orwell’s effort to tally the cost of his books is recounted in his essay, “Books vs. Cigarettes.” I thought of the piece while rifling through some of my books and spotting a volume I borrowed about a decade ago(!) and never returned, a copy of St. John Climacus’s The Ladder of Divine Ascent.

Written in seventh-century Sinai, The Ladder offers spiritual instruction for monks on subjects ranging from prayer and passions to despondency and discerning thoughts.

I could probably justify keeping it. There are few bits inside on the benefits of detachment and non-possessiveness. Wouldn’t keeping the book mean I was helping the owner? Consider the spiritual burden I was alleviating! Of course, that observation cuts both ways. Wasn’t she doing me a favor by taking it back?

When I realized I still had the book I texted the owner and let her know. “No problem,” she answered. “I haven’t missed it . . . yet.” I then moved it to my bedside to read a few more pages before sending it on its rightful way.

Other unowned books are trickier.

Borrowed, Not Returned

Ages ago my employer loaned me a book for a project. I kept it long after. In fact, I kept it long after I lost touch with my boss. I ended up giving the book away because every glimpse of it reminded me the book wasn’t mine. I felt terrible.

I felt even worse when a guy loaned me a book he thought I’d love. Not only did I fail to enjoy the book, I also failed to return it before he died! You can’t take it with you when you go, of course, but it’s even harder when it’s with the last person you loaned it to.

Then there are the books I’ve loaned but never received back. They live like lost prodigals in a far country, up to who knows what shenanigans. I missed a copy of Alan Jacobs’s Original Sin enough that I finally bought another. I felt funny asking the borrower about it and figured it was easier to replace the copy. And _____, if you’re reading this, no worries.

Nowadays when I loan books, I don’t: I just give them away. I have no expectation of their return. It saves me from the stress of thinking about it and gives me a little joy in the gift. Everybody wins.

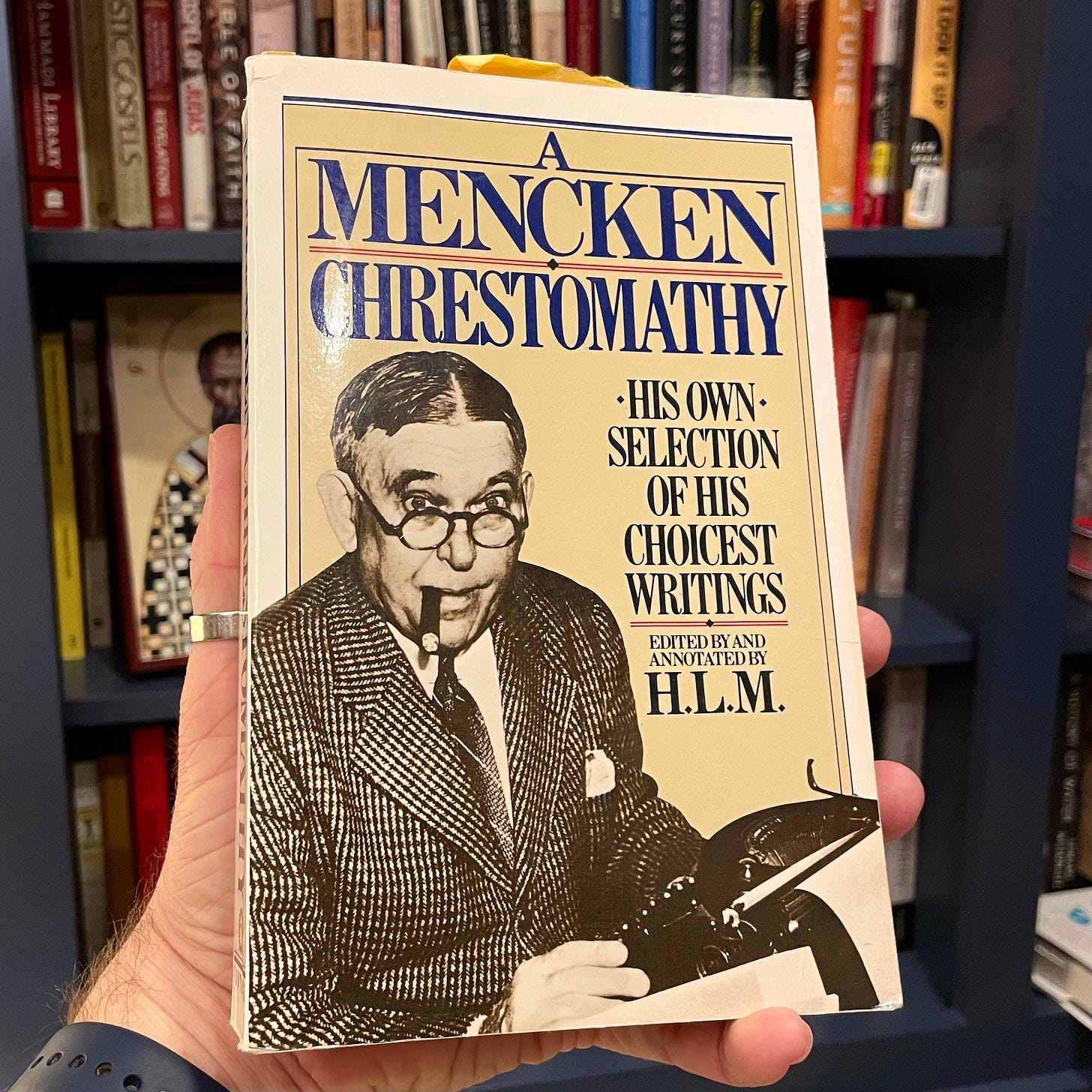

Of course, some books do make it back. I once loaned my Mencken Chrestomathy to a colleague at work; it was a relatively cheap Vintage paperback but the only copy I possessed. She had it forever. She even moved away. Then one day an unbidden email rode an electron rollercoaster to my inbox, and there it sat, inquiring about my mailing address. It was from my long-lost borrower!

I’d already purchased another copy—an older, superior clothbound edition—but the dancing that commenced when my prodigal returned in the post several days later was something for the ages (or at least a fifteen-second Instagram reel). That said, I’m not blinded by such hopes.

Boomerangs return, books do not. Which takes me back to Orwell’s “borrowed and not returned” category, along with his subsequent justification that he’s loaned enough never returned to balance the cosmic scales. He seemed perfectly fine with it. Others, not so much.

‘Let Him Be Struck with Palsy’

Books failing to find their way home represents a longstanding concern. Consider this warning posted in the library of San Pedro monastery in Barcelona:

For him that stealeth a Book from this Library, let it change to a Serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with Palsy, and all his Members blasted. Let him languish in Pain, crying aloud for Mercy, and let there be no surcease to his Agony till he sink to Dissolution. Let Book-worms gnaw his Entrails in token of the Worm that dieth not, and when at last he goeth to his final Punishment let the Flames of Hell consume him for ever and aye.

Too strict, or just right?

Along with warning potential thieves, advising lenders has sometimes prevented lost books. Back in 1852, a writer for Notes & Queries offered a lengthy literary listicle. Item No. 2? “Never lend a book without some acknowledgment from the borrower. . . .” Otherwise, how will you get it back? The presumption seems to be the borrower will hold onto the volume until Jesus returns in the flesh and personally implores the recipient to fork it over. But we know better, right?

At the turn of the twentieth century Book Reporter asked its readers, “Have you ever borrowed a book from someone and purposely not returned it?” Out of thirty-eight published responses, I counted:

Twenty-four nos, including twenty-one hard nos—that is, emphatic rejections. “No, never,” answered one representative respondent. “I would never do that. It does not belong to me.”

Thirteen yeses, including three unapologetic and nine yeses with rationales. An example: “I borrowed the Father Brown Omnibus in about 1982 and I still have it and still read it. I have never mentioned to the owner that I have it and I hope she has forgotten who has it or perhaps she is too polite to ask for it back.”

One uncertain response: “I’m not sure if it was a ‘borrow’ or ‘give’ but the Pelican Brief by John Grisham is still on my shelves, and I believe she has my audio of The Testament also by Grisham. Hmm, did we switch?”

Several of the responses, including the Father Brown and Grisham admissions would seem to validate Orwell’s point. But most people nonetheless felt moral certainty, either positively or negatively, about holding onto books that weren’t theirs. The vast majority of responses, after all, were either emphatic rejections of keeping borrowed books or rationales for doing so. Only three respondents unapologetically admitted keeping books that belonged to others.

Some do view theft as a legitimate means to expand one’s library. “There are three ways of procuring books,” said Rev. Dr. Hugh Black of Union Theological Seminary in a 1907 lecture at Cornell about books and reading. “The first is to buy them, the second is to borrow them, and the third is to steal them. It is better to buy them than to borrow them, it is better to borrow them than to steal them, but it is better to steal them than to read them in a library.”

How could that be? “To really love a book, we have to own it,” Black explained, “it has to be ours, to be a part of us, a part of our minds and thoughts.”

Was it a defense of theft, or an orator’s trick to drive home the importance of fully possessing—internalizing—the books we read? I tend to think the latter. But that’s where the trick turns tricky indeed because if we have internalized the message of a borrowed book, aren’t we less likely to return it? Doesn’t it feel like ours at that point?

50 Shades of Gray

Orwell separated books unreturned from others on temporary loan; does an unreturned book constitute theft, or merely a form of permanent loan? Returning books we’ve borrowed can feel weird, even embarrassing. And not just because we feel as though we’re now letting go of something core to our self-understanding.

Simply waiting too long can bring on a measure of humiliation. It’s almost best to keep the book and, like the Book Reporter respondent above, simply hope the lender forgets to ask about it. Ever done that? I have. Admittedly, it didn’t leave me feeling any better.

Still, the morally ambiguous middle ground is appealing. It avoids outright theft—after all, we’d return it if they asked—while also avoiding the embarrassment of turning up with a book long after the accompanying generosity has long expired. Hence the reason Orwell has some books “borrowed and not returned” and others “temporarily on loan.” The first group he plans on keeping until Armageddon; the second he plans to presently return—unless, of course, he dawdles and they slide into the oblivion of the other category.

Perhaps these are simply the gray areas of our cultural norms around borrowing books, neither exactly moral nor immoral but easily slipping one way or the other based on memory, intent, convenience, and similar considerations. Just pause and look at your own library. How do you feel about what you see—or don’t?

I recently surveyed my entire library and am relatively certain I don’t possess any that belong to others at this point. Where the pangs of guilt stab me these days? Review copies. In his 1899 farce Her Majesty the King, Irish poet James Jeffery Roche said, “Some men borrow books; some men steal books; and others beg presentation copies from the author.”1 Such books amounted to a third of Orwell’s collection.

It’s a fraught transaction. I receive review copies from time to time from publishers, publicists, and authors. Sometimes I request them directly. A few times I’ve received the book, read it—or enough of it—and decided against writing a review. Why?

I disliked the book for one reason or another and didn’t want to write a negative review. I enjoy reading a scorcher but hate writing them. But then, there I am: in receipt of a freebie I now intend on passing along instead of putting to the purpose for which it was given. It nags me every time. Should it? Or am I doing the author a favor by letting it slip by? What happens if I don’t give it away? Does my guilt accumulate the longer I let it sit on my desk?

Now for you: Did you look over your library just now? Do some quick math for me. How many books do you currently possess on loan? How many books have you loaned you’ve never seen since? Leave your answer—and any other thoughts about book borrowing and book stealing—in the comments. And if you have any helpful tips on those stolen Pushkins, please pass them along to the inquisitive folks at Europol.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Roche attributes the line to one “Ben Haround” but seems to have made him up.

When I was in high school, my parents loaned a Frank Peretti book to another family. My mom wanted that book back badly. A couple of years passed. “I don’t think they have any intention of giving that book back,” my mother finally said. As fate would have it, I had a sleepover planned at said family’s house. My mom instructed me to scour their bookshelves and bring our Peretti book back home. I did as I was told. Sure enough, there it was: “This Present Darkness,” comfortably situated among their other books, like it belonged there! I pulled it out carefully, checked the front cover. Our family name was inscribed in the front, a reminder of this book's true owner. I slipped the book into my backpack and — sting operation complete — triumphantly produced the volume upon my return home. I was given a hero's welcome.

You had the guilt creeping up in me as I read along. Yes, there are some borrowed books on my shelves (The Essential C.S. Lewis and a Dorothy Sayers mystery - from a church library which no one ever uses or keeps track of...) and some other non-fiction volumes from generous friends. However, in my defense, I liberally let people borrow from our shelves and quite frequently never lay eyes on the books again (still trying to track down A Landscape of Dragons by Michael O'Brien!). Once I was walking along a street in Switzerland and found four copies of "For the Children's Sake" by Susan Scheaffer set out in a box labelled "free". This has been wonderful as it is one of the first books I recommend to new homeschoolers and I have been able to simply pass them out, saying "no need to return this to me; you can keep it or pass it on" :)