The Bible Is Weirder than We Usually Realize

A Textual Romp Through One of the World’s Better Known Classics

I grew up, perhaps like many of you, in a house with several Bibles. Both my parents had their favored editions—plus there were various versions and translations, some in stodgy English, some in trendy English, some with study notes, some with chain references, some with red letters, some in paper covers, some in leather; they even had an Amplified Bible, which was popular for about twelve minutes back in the day. But for all the variety, the core thing—the text itself—was pretty standard.

It wasn’t always like that, and the typical formats in which we encounter the Bible—those are all fairly modern. But there was very little “standard” about the premodern Bible. It would actually be pretty hard to talk about the Bible the way we mean that today.

I was reminded of this after a delightful conversation last week with Trevin Wax. We were talking about study Bibles, and I recalled one set to release in 2027 from Oxford University Press, The Ancient Christian Study Bible: The Bible of the First Millennium AD, edited by Eugen J. Pentiuc and Paul M. Blowers.

Different Strokes

If you read the press release announcing the project, you’ll notice what I mean:

The ACSB will use as textual bases the Septuagint text (Vaticanus Codex) for the Old Testament, and the Byzantine Textform (Patriarchal Text, Constantinople, 1904) for the New Testament.

We’ve careened off the standard path already. Today the underlying Old Testament text in most Bibles is the Masoretic text, the oldest copies of which only go back about a thousand years. But for those first thousand years?

There was a proto-Masoretic text of some sort—probably better to say of several sorts—but Christians didn’t much use it (or them). In the Greek-speaking East, Christians used the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures known as the Septuagint, which we’ll explore further in a moment. In the Latin West, they used a Latin translation of the Septuagint called the Old Latin and then, thanks to Jerome, the Vulgate, which translated a Hebrew text and some Greek and Aramaic bits into Latin.1 In the Syriac-speaking East, they used the Peshitta, which was translated from Hebrew and Greek. And of course, there are others as well, including the Geʽez translation used by the Ethiopian churches.

But these are just labels. Under the hood everything is considerably messier than you might guess. Just take the Peshitta (still used, by the way, in the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Assyrian Church, Syriac Catholic Church, and others, including many of the St. Thomas Christians of Kerala, India, and the Assyrian Pentecostal Church).

Like Jerome’s Vulgate, the Peshitta Old Testament was mostly translated from the Hebrew, though tweaked to mirror the Septuagint. The New Testament was translated from the Greek, but neither the Old Testament nor the New included all the biblical books. The Peshitta Old Testament followed the Palestinian Jewish canon and excluded several books favored by Hellenistic Jews and later Christians, such as Tobit, Judith, and the Maccabean books. And the Peshitta New Testament boasted several other oddities; for instance, Paul’s letters actually come after the Catholic epistles. So the Letter of James follows Acts, not Romans.2 Further, several of the Catholic epistles—2 Peter, 2–3 John, Jude—and Revelation never made it in. These were later translated but have minimal purchase in the liturgical life of these churches even today.

Revelation became popular in the West but never in the East. And so it’s not just the Syriac Church that downplays its use. The entire Greek/Byzantine and subsequent Russian Orthodox traditions downplay it also. You can stand in an Eastern Orthodox Church your entire life and never hear Revelation read aloud; it’s not part of the lectionary. It’s considered canonical and suitable for private devotion, but it’s never read in church. St. Ignatius Orthodox Press publishes a standalone Holy Apostle—a volume that contains Acts and the rest of the epistles. Revelation is included as an appendix.

Of course, it’s different for the Coptic Orthodox. Alexandrian Christians approved of Revelation. Bishop Athanasius included it in his famous 39th Festal Letter that outlined the New Testament canon most Christians follow today, making the year 367 CE the first time the standard 27 books were all enumerated in one list; the author of Revelation had been dead for nearly three centuries at that point. Even then, the Copts only read it liturgically once a year—during Holy Week.

Back to The Ancient Christian Study Bible and its use of the Septuagint.

What’s Your Source?

Diasporic Jews took up Greek and translated the Hebrew Scriptures into their new language. As Jaroslav Pelikan noted in Whose Bible Is It? this is fundamentally how the Bible became world literature. There’s a legend about how this was done, but there’s little historical evidence of the legend. Instead, it seems the books were translated ad hoc, as needed. And there are many versions even of these. The ACSB is using the Vaticanus Codex as its base, but there are two other textual witnesses, Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus, not to mention later Greek translations by Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion. The ACSB promises to highlight these differences in its textual notes.

The ACSB New Testament also reveals some historical notables. Most modern English Bibles—say, the New Revised Standard Version, English Standard Version, New International Version—translate from what’s called the Critical or Eclectic Text. Scholars have assembled this text by collating the earliest Greek manuscripts to reconstruct what the original New Testament likely said. The main idea? Older manuscripts are closer to the original, and careful comparison can help “correct” later editorial changes and copying mistakes.

But the Critical Text isn’t the only option for translators. The Majority Text employs the most common readings found in thousands of later Greek/Byzantine manuscripts. The main idea here? A consensus from the manuscripts used and copied most widely, validated by sheer volume and preserved through tradition over time, probably offers the best option. Very few Bibles, however, actually use the Majority Text.

More popular, at least in terms of sales, is the Textus Receptus, first compiled by Erasmus from later Greek/Byzantine manuscripts. It’s the basis for the King James Bible and the New King James Version. This leads to an amusing observation: Protestant fundamentalists who insist on using only the King James are championing an English version of a Greek Orthodox Bible first edited by a Roman Catholic monk. Providence plays its jokes.

But, as mentioned in the press release quoted above, the ACSB New Testament is actually based on none of these. It translates the Patriarchal Text, also called the Antoniades Text, first published in 1904 by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. Like the Majority Text, it’s a product of the Byzantine manuscript tradition, but instead of basing its value on the earliest dated manuscripts or the largest number of copies circulating in the medieval Byzantine world, the governing assumption is that liturgical continuity and ecclesial authority vouchsafe the text—emphasizing ongoing community use over academic reconstruction.

All of these traditions are in substantial agreement—that is, about 85 percent of the time. But that means there are still quite a few variances.

Changing It Up

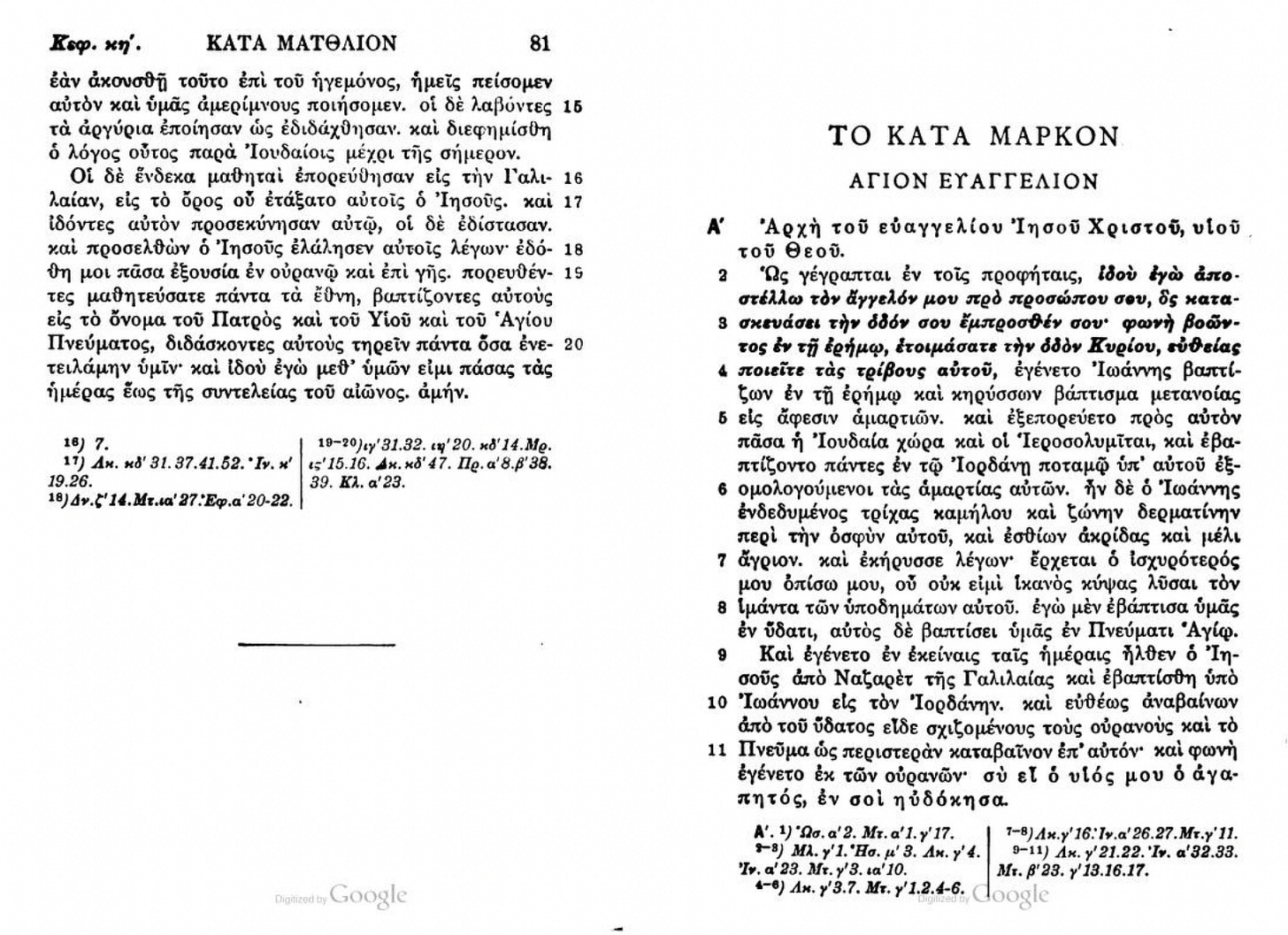

Here’s one to chew on, a few different versions of Mark 1.2–3:

As it is written in the prophet Isaiah, “See I am sending my messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way; the voice of one crying out in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.’” (NRSV, Critical Text)

As it is written in Isaiah the prophet, “Behold, I am sending my messenger before you, who will make ready your way, a voice calling in the wilderness, ‘Prepare the way of the Lord and make his paths straight.’” (Antioch Bible English Translation, Peshitta)

As it is written in the prophets, Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, which shall prepare thy way before thee. The voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths straight. (King James Bible, Textus Receptus)

As it is written in the prophets: “Behold, I send my messenger before your face,

who will prepare your way—the voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.’” (Antoniades/Patriarchal Text, translated pretty ably by ChatGPT)

There’s one glaring difference between the first two versions and the second two. The Critical Text and the Peshitta both reference Isaiah by name, but the Textus Receptus and Antoniades do not. They both simply say, “the prophets.” The reason? The earliest Greek manuscripts contain an error. The second part of the quote does indeed come from Isaiah (chapter 40, verse 3), but the first part—“I send my messenger”—actually comes from another prophetic passage: Malachi 3.1.

At some point the incongruity bothered Byzantine editors, and they “fixed” the “mistake” by scrubbing the reference to Isaiah and pluralizing prophet to prophets. The Critical Text and the Peshitta preserve the earlier reading. The Textus Receptus and Antoniades contain the correction, as does the Majority Text.

Does it matter? Depends on what matters to you.

Bigger issues might come into play if you lean into these variances. For instance, the episode usually known as “the woman caught in adultery” contains a beloved story, demonstrating the deep compassion of Jesus. And it’s not present in the Critical Text; the Peshitta is also missing it. The Textus Receptus and Majority Text include it, as does Antoniades. In many Bibles drawn from the Critical Text the story is included in brackets with a note saying it’s missing from the source. In the Revised English Bible, it’s actually attached as an appendix to John.

The passage has a weird and wonderful history. The most ancient manuscripts indeed do not contain the story; instead, it appears in later manuscripts—though not always in a standard place. Some place it earlier or later in John, and other later manuscripts even drop it in Luke’s Gospel! You can almost imagine later editors scrambling to fit it in someplace: “It’s too good. Don’t lose it. Just put in there.”

But are we really going to yank the story because it’s not in the earliest witnesses? “No,” as George and Ira Gershwin prepared us to say, “they can’t take that away from me.”

Going Deeper

Some people find all of this variability unnerving. I find it fascinating—especially when easily packaged for my own reading. As a result, I’m eagerly awaiting The Ancient Christian Study Bible. But there are easy ways of accessing some of this diversity right now. I mentioned the Holy Apostle published by Saint Ignatius Orthodox Press. They also publish a Gospel book, as well as a Psalter and a collection of liturgically used Old Testament passages, the Prophetologion. The New Testament books use the Antoniades/Patriarchal Text and the Old Testament books use the Septuagint. What’s more, they’re very beautiful and affordable editions.

You can also get contemporary translations of the Septuagint, principally the New English Translation of the Septuagint and The Lexham English Septuagint. Both contain different versions of biblical books where diversity emerges among the Greek versions. You’ll find all sorts of interesting puzzlers there, such as the fact that the Septuagint Jeremiah is shorter than the Masoretic text, and several of its passages come in a different order—and the Septuagint seems to represent the earlier version of the book! If, by the way, you want more background on the Septuagint a great place to start is Timothy Michael Law’s When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible, published by Oxford University Press.

If you’d like to launch into the Peshitta, the best entry point is the Peshitta English New Testament, published by Gorgias. Like the Saint Ignatius volumes, it’s quite elegant.

Along with these firsthand artifacts, the history of the Bible can illuminate much of this complexity and variety. Several recent(ish) histories stand out for me, and I recommend them all, starting with Nathan Mastnjak’s Before the Scrolls: A Material Approach to Israel’s Prophetic Library (Oxford University Press, 2023). Mastnjak looks back to the materials and processes used to write the original texts of the scriptures and helps explain where this sort of variability might have started—from the inception of the books themselves. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature. He, for instance, explores all those variances in Jeremiah.

John Barton has given us two wonderful historical studies: A History of the Bible: The Story of the World’s Most Influential Book (Viking, 2019) and The Word: How We Translate the Bible—and Why It Matters (Basic Books, 2023). Both look at the fascinating and fraught nature of wrestling with this ancient text and float an arresting observation: Both Judaism and Christianity use the Bible but don’t flow directly from it and have to read it in particular ways to make their respective models “fit.” Once he points it out, you can’t unsee it.

Konrad Schmid and Jens Schröter’s The Making of the Bible: From the First Fragments to Sacred Scripture, translated by Peter Lewis (Belknap, 2021), shows how the formation of the Bible contributed to Jewish and Christian culture and how they eventually diverged.

Finally, there’s Bruce Gordon’s magisterial The Bible: A Global History (Basic Books, 2024). Gordon tells the story all the way from the Bible’s inception to its spread throughout the world, including into China, Africa, and the Pentecostal revivals in the “global south.”

This only scratches the surface of how weird and nonstandard the Bible can be. Whatever your personal background or beliefs, if you find that intriguing, I invite you dig deeper. Curiosities await.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend.

And! More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

Jerome only translated a few of the deuterocanonical books, usually called the Apocrypha by Protestants; the rest were pulled into the Vulgate from the Old Latin translation of the Septuagint since the sources were mostly Greek.

I’ve long wondered if Martin Luther’s attitudes about both James and Romans—and the ruckus those attitudes caused—would have been different if he read the Peshitta.

This is really interesting. I have seven different versions of the Bible, and my favorite for everyday reading is the Common English Bible. I also use the Orthodox Study Bible (Thomas Nelson), because I like its commentary.

One of my favorite Babylon Bee headlines was "KJV-Only Pastor Admits He Is NIV-Positive."

Really appreciate you sharing this info, Joel. Textual criticism is a fascinating (and essential) discipline. Looking at all the variants in the New Testament in its more than 5800 Greek manuscripts, we could easily doubt how we can have confidence at all in the Bible. But in the end, not one place in the New Testament does a doctrine of our faith stand or fall on a variant. In other words, even though we may be unsure about how to translate less than 1% of the New Testament, we can understand 100% of what God wants us to know about life and salvation.

I'm grateful you brought up translations, as they have amazing value (including 15,000 New Testament manuscripts in other ancient languages). I'm thinking particularly of St. Peter's epistles, where the majority of his Old Testament quotes come from the Septuagint (a translation!). This gives amazing credibility to the value of our modern translations as indeed representing the Word of God.

As an aside, Dr. Dan Wallace and his team at The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts are some of the many capable scholars we have to thank for preserving and defending the ancient manuscripts. You might also enjoy watching Dr. Wallace's talk, "Is What We Have Now What They Wrote Then?" on YouTube.