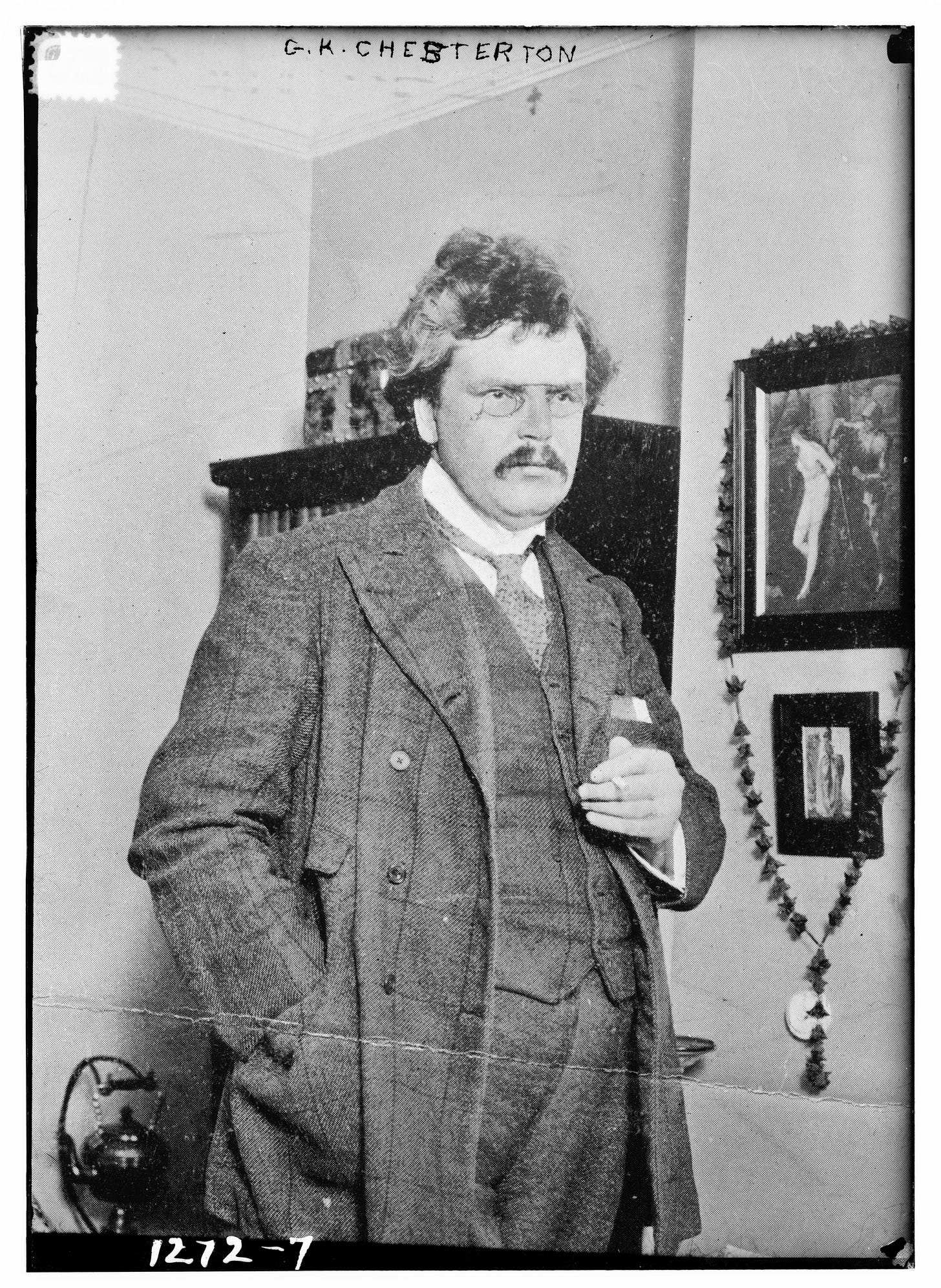

G.K. Chesterton: The Man Behind the Fence

Chesterton’s Persistence as a Source for Generative Insight

Certain authors have way of staying relevant for their core readers while finding new audiences, sometimes for surprising and roundabout reasons. Though G.K. Chesterton is best known for his essays, poetry, apologetics, and detective stories—Father Brown being a favorite character—today you’re just as likely to find economists and thought leaders talking about Chesterton’s Fence.

Trendy, Century-Old Heuristic

“When you come across something that doesn’t make sense to you,” says Russ Roberts, explaining the concept in his book Wild Problems, such as “a fence in the middle of nowhere with no apparent purpose—you might be tempted to tear it down. Before you do, you should try to find out why it’s there—it might have a cause or purpose that isn’t obvious.” Roberts applies the idea to choosing whom to marry; in his example tradition is the fence someone might eliminate without adequate appreciation.

Similarly, Farnam Street touts Chesterton’s Fence as a means for better decisions. “A core component of making great decisions is understanding the rationale behind previous decisions,” says the site, highlighting the trend of scrapping hierarchical org charts and incoming managers who make sweeping changes without appreciating prior arrangements.

“If we don’t understand how we got ‘here,’” says the site, “we run the risk of making things much worse. . . . The first step before modifying an aspect of a system is to understand it. Observe it in full. Note how it interconnects with other aspects, including ones that might not be linked to you personally. Learn how it works, and then propose your change.”

In his excellent Substack Bastiat's Window, economist and healthcare scholar

appeals to Chesterton’s Fence when addressing the politicization of medicine. After the American Medical Association and the American Association of Medical Colleges pushed new speech codes in 2021, Graboyes objected. “Part of the ongoing problem in politicized medicine,” he says, “is a desire on the part of reformers to jettison that which they do not fully understand—such as the value of free speech, even when that speech seems odious, distasteful, or misinformed.”And, writing last December, American Enterprise Institute senior fellow Timothy Carney advised Elon Musk to heed the warning of Chesterton’s Fence when rashly contemplating changes at Twitter—er, X. Safe to say Musk didn’t listen; advertising revenues at the site continue to plummet, and the user experience gets shakier by the week.

Giving Chesterton a Vote

The concept of the Chesterton Fence comes from a passage in Chesterton’s essay, “The Drift from Domesticity,” collected in his 1929 book, The Thing:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Chesterton’s Fence doesn’t rule out innovation or reform; rather, it insists we can avoid needless destruction and downstream harms by simply ensuring we more fully understand what impedes our intended progress. Sometimes we fail to appreciate past wisdom and are forced to learn the hard way.

The foundation for the concept involves a deeper insight highlighted in chapter 4 of Chesterton’s 1908 classic, Orthodoxy, known as the Democracy of the Dead. “Tradition means giving a vote to the most obscure of all classes,” he explains,

our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. . . . All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our father.

The past not only speaks to the present, it’s in constant conversation if we’re attuned to the exchange. And no one makes that clearer than Chesterton himself, whose entire body of work both warrants and rewards consideration. “He leaves behind a permanent claim upon our loyalty,” said T.S. Eliot upon his death, “to see that the work that he did in his time is continued in ours.”

Thankfully, Chesterton made it easy. Indeed, he claims fans on the right and left and from all points in between and beyond. “Surely no other writer in any century can claim a following that includes Irish rebels, Latin American fabulists and Christian apologists,” said Allen Barra of Chesterton’s strangely inclusive appeal. And being Christian is no requirement. Economist and Santa Clara University law professor David Friedman is both an atheist and a Chesterton fan; he refers to his position as “Catholicism without God.”

Beyond the Fence

As a writer and thinker, Chesterton showed special skill in framing issues. You can see it in how he defended tradition by linking it to democracy, two ideas in possible conflict. Indeed, as he said, “Tradition may be defined as an extension of the franchise.” He wrote this during the height of the women’s suffrage movement, where extending the franchise was a regular feature of conversation. Chesterton repurposed the conversation for his own ends—and note the structure of his appeal.

A master of dichotomy, inversion, and paradox, Chesterton would regularly pair dissimilar items and show their commonalities, or pair similar items and highlight their differences. Take this classic example from 1924 and cited by Graboyes,

The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of Conservatives is to prevent mistakes from being corrected. Even when the revolutionist might himself repent of his revolution, the traditionalist is already defending it as part of his tradition.

It’s an absurdist take, but we can see versions of this dynamic play out in politics every day. Chesterton’s unique ability to frame paradoxes offers us new and generative ways to see the world—not to mention all its problems and opportunities.

“Chesterton turns everything upside down and reveals old truths in fresh ways,” said Chesterton aficionado and author Trevin Wax when I asked him about his favorite Chesterton book. “He does that with many books, but if I had to pick one, it would be Orthodoxy. . . . I’ve read it the most, and it continues to pay dividends in my thinking.” Wax has honored Chesterton’s contribution by publishing an annotated edition.

I asked Wax what someone should try if they’ve never read any Chesterton.

“Chesterton stands out for the sheer variety of genres he wrote in,” he said. “At his core he was a journalist whose essays later turned into books. He penned several plays and wrote literary appreciations and criticisms of people like Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Thomas Carlyle. Then there are his detective stories and poems. People recited his epic Lepanto in the trenches of World War I, and, more recently, the atheist Christopher Hitchens lauded Chesterton as one of England's last great poets.”

With so much to choose from, how do we find our way in? “It’s a massive house with many possible doors of entry,” he said. “I would select a book based on your entry of choice. For apologetics, I recommend Orthodoxy. For biographies, I would point you to his work on St. Francis of Assisi. For fiction, I would pick Manalive. For literary books, his critical study on Charles Dickens. For plays, Magic. For books of essays, The Defendant.” Beyond these, Wax also recommends Dale Ahlquist’s The Story of the Family and another essay collection, In Defense of Sanity.

Another entry point for both new readers and longstanding fans are biographies and quote collections. There are several available. When I was at Thomas Nelson, I published two volumes by biographer Kevin Belmonte, Defiant Joy and The Quotable Chesterton. Extracts offer a low bar because Chesterton’s writing works so well at the level of the zinger and squib, and his talent for paradox and dichotomy surges to the surface in such collections. Any random page may prompt both a smile and an insight.

But however you venture in, join the democracy of the dead and give Chesterton a vote. After all, the best argument for engaging Chesterton’s ideas beyond Chesterton’s Fence may actually be . . . Chesterton’s Fence. If you don’t know why he’s been so diligently and joyously read for the last century, you probably shouldn’t dismiss him until you do.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post:

Thank you Joel! Sharing with Chesterton friends if they're not here already. I ordered Orhtodoxy from Amazon a couple of years ago and it came in an Amazon reprint that did the writing no service. Dense and hard to read, unlike the writing itself. Perhaps if I use my pen and make it more my own with marginalia!

A favourite Chesterton quote in my file: "Logic, then, is not necessarily an instrument for finding truth; on the contrary, truth is necessarily an instrument for using logic—for using it, that is, for the discovery of further truth and for the profit of humanity. Briefly, you can only find truth with logic if you have already found truth without it."

G. K. Chesterton (Daily News, Feb 25, 1905)

I’ve been reading GKC for over thirty years. I’ve now collected all of his more than 100 books in early editions save one (his very rare illustrated profile of William Cobbett). My decades-long habit is to read “Orthodoxy” every January--along with Kuyper’s “Stone Lectures” and Calvin’s “Golden Booklet.”