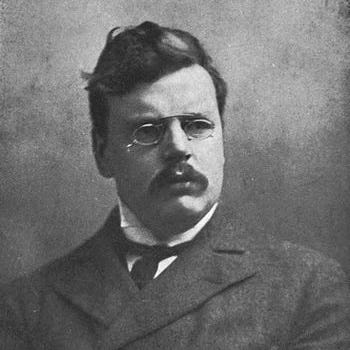

G. K. Chesterton: Underrated Model for Social Engagement

As the Landscape Turns Ugly and Divided, a Prolific Englishman Provides a Positive Vision for Connection

A friend’s theater company staged G. K. Chesterton’s play, Magic, in 2011. He asked me to say a few introductory words about the author on opening night. Here’s a version of what I said, drawing on Kevin Belmonte’s excellent biography, Defiant Joy, which I had published earlier that same year at Thomas Nelson.

It was the first day of school, and young G. K. Chesterton and another boy tangled in the school yard. Finally wearied and exhausted, his opponent quoted Dickens or another author and the two dropped their fists and commenced a relationship that lasted the rest of Chesterton’s life.

It’s the perfect story to introduce him. When I think of Chesterton, two words come to mind: truth and friendship. He was ready to fight over what he deemed true but was essentially sociable and cared as deeply for people as ideas.

None of Chesterton’s relationships reveal this better than his friendship with playwright George Bernard Shaw. Chesterton and Shaw had a very public and perpetual fight going. Chesterton not only dedicated a chapter to Shaw in his book Heretics, he later dedicated a whole book to the man and his ideas—ideas he loathed, but a man he loved. Despite their debates, Chesterton and Shaw were lifelong friends.

The nature of their disagreement helps explain the relevance of Chesterton to his own time and gives us a sense of his place in our own. He was born in 1874. Chesterton grew up in world recently built by steam power and industrialization. He saw the birth of electricity and automobiles. Science and technology promised to liberate man, especially once the shackles of religion had been shed.

The progressive Shaw was an eager participant in this shedding, happy to toss off old modes and norms. Meanwhile, Chesterton found himself standing against this progressivist tide. He was not opposed to science and technology; he could appreciate a lightbulb as readily as the next person. But he also valued illumination from a source Shaw and others were eager to discard.

That illumination dawned slowly in his own life. He went through a brief but traumatic period of intense depression, a young man adrift on an ocean whose currents swirled in different directions than those of his childhood. He confessed being captured by grotesque and troublesome thoughts. He dabbled in the occult. And then, as he despaired of living, he found his bearings. Gratitude offered a way out.

He suddenly, by God’s grace, had the thought that his very being was a gift and each day an unexpected opportunity. Profoundly, deeply, thoroughly, pitifully thankful, he began looking for who he should thank, and that pursuit of thanksgiving marked the rest of his days—and also put him at odds with many of his contemporaries.

Chesterton became a happy warrior for traditional Christian belief in an age determined to ignore every syllable from a priest or philosopher older than itself. You can see why he and Shaw—and others like H. L. Mencken, H. G. Wells, and the pre-conversion T. S. Eliot—might have their differences. But his congenial nature meant the animosity was mostly one-sided, and real friendships flourished amid the jousting.

One point of friendly jabbing involved the play, Magic. Shaw had been after Chesterton for years. Write a play, he insisted over and again, even pressuring Chesterton’s wife to join him in a ruse to get him to do so. After literally years of pressuring, Chesterton finally knocked out Magic, a play that insisted in peculiar ways on all the particulars of his worldview. It was an instant hit in England as well as America.

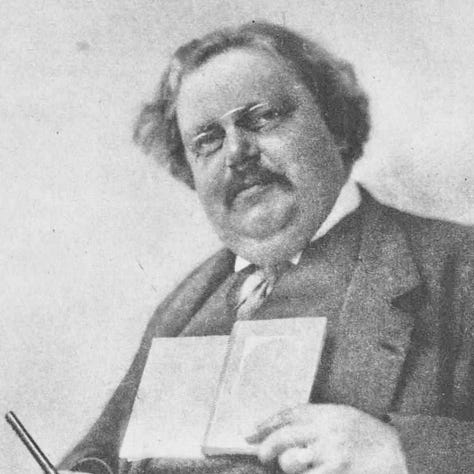

Chesterton needed decidedly less prodding to produce the rest of his output. He took to pen and paper as quickly as he did to beer and beef. The author of some eighty books and articles beyond counting, Chesterton profoundly influenced his generation and all those succeeding with such works as Heretics, Orthodoxy, and The Everlasting Man—the last of which C. S. Lewis credited for his own return to faith.

When Chesterton quietly converted to Catholicism in 1922 a journalist jumped him at his property and asked him about his conversion. Chesterton insisted that he join him for tea and then mind his own business. But Chesterton’s faith was his business and the business of every reader. He talked more of faith than anything else. And if you’ve read much of his work, you know that he talked about everything from Dickens and free-love to eugenics and cheese.

The world’s social structures, economics, and politics—for Chesterton none of it reflected the true glory and love for which people were created. He wasn’t alone in his concerns. Some saw it his way. T. S. Eliot, his foe for many years, eventually converted. Chesterton later reached out in friendship and created another ally.

“It is not bigotry to be certain we are right,” he said in one if his many books; “but it is bigotry to be unable to imagine how we might possibly have gone wrong.” Indeed— though it’s hard to go wrong befriending others and thinking well of your foes.

What I take from his example is a twin conviction: truth is worth fighting for and people are worth honoring. If you can do both, you’re as great as you are good. And Chesterton was one of the greats.

¶ Thanks for reading. Please consider sharing this post with a friend.

¶ Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Great article!

Nothing says loving your enemies like joining them at the nearest pub after a debate in a lecture hall.

I have been a Christian for decades and have viewed the world through the lens of Scripture. Chesterton taught me that because God is absolutely real and all He says is true, I can look at the entire world and see Him and His patterns. Reading “Orthodoxy “ changed my life because Chesterton showed me how to see the Lord everywhere. I have never been the same.