Protect Good Reading from Bad Schooling

Augustine, Jerome, and Montaigne on the Educational Virtue of Following Your Whims

I’ve got five kids, three still of school age, and they’re all back in class. Thank God! Few things make me happier than the start of summer vacation—except perhaps when it’s over. I might like that even more.

Still, driving my brood to their various schools the other morning, I idly noodled on the artificiality of education. Speaking is natural. Most of us are doing it by two or three, even if we can’t yet take profitable command of the complexities of expression. But for words on a page there’s nothing inherent in the human mental kit that manifests the ability to decipher letters or understand their corresponding sounds, let alone how to manipulate the subtler matter of grammar and syntax in writing.

In his Confessions, Augustine described how he learned how to speak. “I would listen to the words,” he said, “and immediately I would work out from their positions in different sentences what they meant; and, as soon as I had learnt to get my tongue around them, I began to string them together in sentences of my own, in order to convey my own desires” (1.8.13, translated by Philip Burton). Easy peasy. But words on a page were different, harder:

As for the reason why I hated the Greek literature in which I was steeped as a boy—for that I have still found no satisfactory explanation. I had fallen in love with Latin literature—not, that is, with the texts taught by my earliest teachers, but the literature taught by the so-called “grammarians.” My primers of reading, writing and arithmetic I found more of a burden and a punishment than the whole of Greek literature put together. . . . But it was through those books that I gradually acquired the ability to read any piece of writing that I came across, and to write myself anything that I wished to write; which ability, once gained, I still possess. (1.13.20)

Looking back on his experience, Augustine criticized the curriculum and the methods. “Education is a big business,” he said, and if students resisted their teachers, “out came the cane” (1.16.26). Yikes!

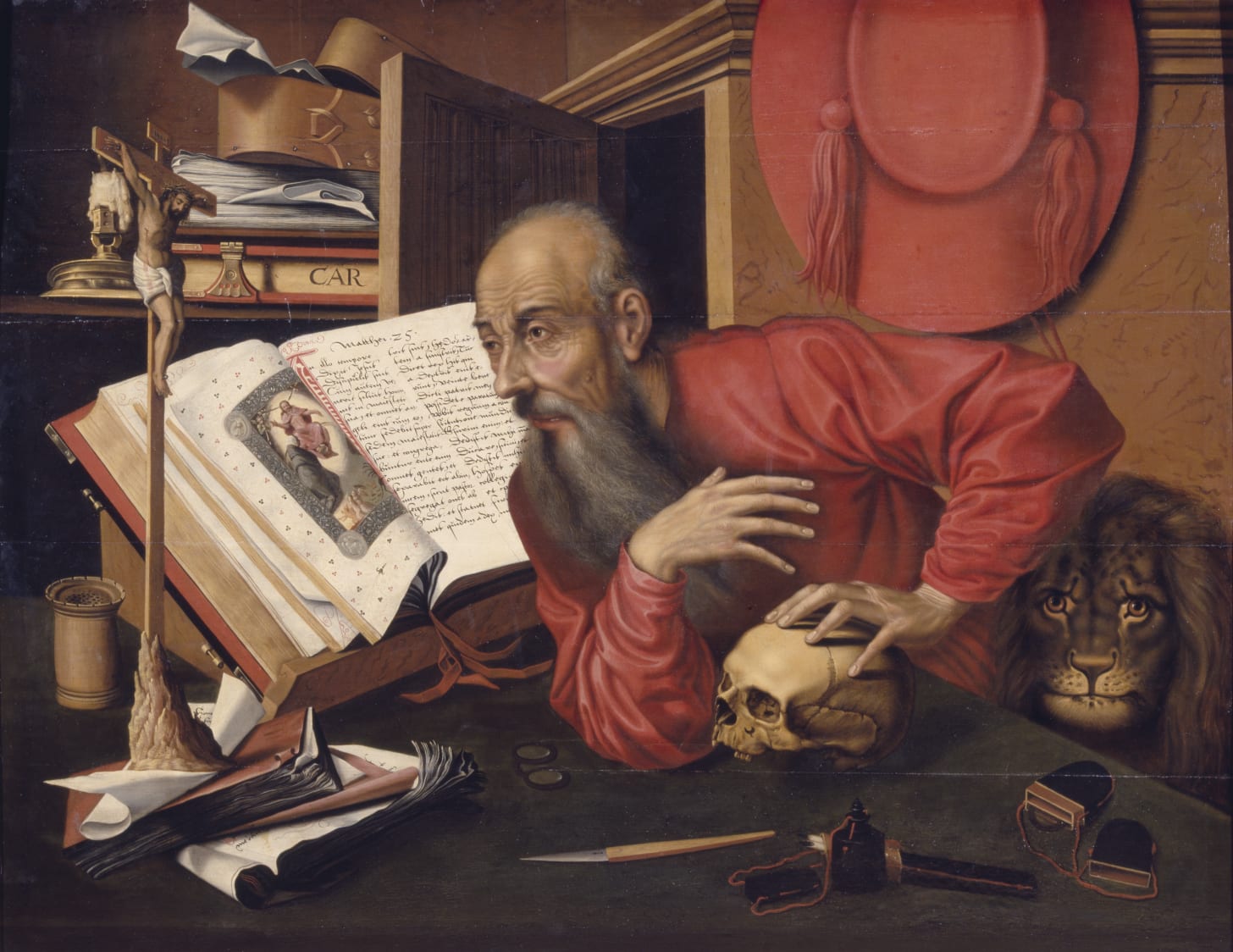

St. Jerome’s regimen sounds a bit more gentle and solicitous. Responding to a woman named Laeta asking him for advice on educating her daughter Paula, Jerome suggested the following:

Have a set of letters made for her, of boxwood or of ivory, and tell her their names. Let her play with them, making play a road to learning, and let her not only grasp the right order of the letters and remember their names in a simple song, but also frequently upset their order and mix the last letters with the middle ones, the middle with the first. Thus she will know them all by sight as well as by sound.

When she begins with uncertain hand to use the pen, either let another hand be put over hers to guide her baby fingers, or else have the letters marked on the tablet so that her writing may follow their outlines and keep to their limits without straying away.

Offer her prizes for spelling, tempting her with such trifling gifts as please young children. Let her have companions too in her lessons, so that she may seek to rival them and be stimulated by any praise they win. You must not scold her if she is somewhat slow; praise is the best sharpener of wits. Let her be glad when she is first and sorry when she falls behind.

Above all take care not to make her lessons distasteful; a childish dislike often lasts longer than childhood. (Letter 107, translated by F. A. Wright)

I think I know where Maria Montessori got some of her ideas. How many kids are put off education or don’t consider themselves learners because of lousy experiences in school? Jerome’s advice to Laeta was to stay focused on the long game; learning doesn’t do us much good if we come to hate it when school’s out.

Montaigne’s father would have resonated with Jerome’s advice. His approach with his son was both gentle and eccentric. “Among other things,” Montaigne recalled in his Essays, “he had been advised to teach me to enjoy knowledge and duty by my own free will and desire, and to educate my mind in all gentleness and freedom, without rigor and constraint“ (1.26, “On the Education of Children,” translated by Donald M. Frame).

And yet Montaigne’s father would go to extremes to engineer the right educational environment of his son—including hiring a German tutor who knew none of the family’s native French and forbidding use of anything but Latin in the home so Montaigne would learn it as his primary language.

My late father, having made all the inquiries a man can make, among men of learning and understanding, about a superlative system of education, became aware of the drawbacks that were prevalent; and he was told that the long time we put into learning languages which cost the ancient Greeks and Romans nothing was the only reason we could not attain their greatness in soul and in knowledge. I do not think that that is the only reason. At all events, the expedient my father hit upon was this, that while I was nursing and before the first loosening of my tongue, he put me in the care of a German . . . wholly ignorant of our language and very well versed in Latin. This man, whom he had sent for expressly, and who was very highly paid, had me constantly in his hands. There were also two others with him, less learned, to attend me and relieve him. These spoke to me in no other language than Latin. As for the rest of my father’s household, it was an inviolable rule that neither my father himself, nor my mother, nor any valet or housemaid, should speak anything in my presence but such Latin words as each had learned in order to jabber with me.

This immersive approach paid off later when it came to reading. “The first taste I had for books,” he said, “came to me from my pleasure in the fables of the Metamorphoses of Ovid. For at about seven or eight years of age I would steal away from any other pleasure to read them, inasmuch as this language was my mother tongue, and it was the easiest book I knew and the best suited by its content to my tender age.” Montaigne wanted nothing to do with whatever vernacular adventures kids his age were reading, “rubbish on which children waste their time.”

Montaigne’s tutor put his passion for reading to good use. He let his pupil follow his whims, nudging and directing, rather than dictating a strict course of study.

For by this means I went right through Virgil’s Aeneid, and then Terence, and then Plautus, and some Italian comedies, always lured on by the pleasantness of the subject. If he had been foolish enough to break this habit, I think I should have got nothing out of school but a hatred of books, as do nearly all our noblemen. He went about it cleverly. Pretending to see nothing, he whetted my appetite, letting me gorge myself with these books only in secret, and gently keeping me at my work on the regular studies.

What do I take from all this? Education is challenging, and regimented learning is not always the right course. I know the arguments for it, but how many students are simply turned off from learning because the subjects bore them to distraction or grind them to discouragement? Augustine mastered Latin but, cane or not, never did learn his Greek.

There’s something to be said for letting students follow their own whims and interests, learning as they go rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all track from above.

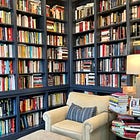

My education, especially by high school, was accidentally similar to Montaigne’s. I attended a small Christian school that placed no serious emphasis on literature, sadly. But my dad was an English teacher at a local public high school. We had an ample home library, and he placed no real restrictions on what I read.

For school I read Johann Wyss’s Swiss Family Robinson—possibly the worst novel ever. But at home I read everything from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird to David Morrell’s First Blood. I also read plenty of history, politics, economics, and theology—all subjects my dad cared about and which I loved too.

Naturally, this meant I ended up with an idiosyncratic education complete with gaping holes. I, for instance, read most of the Tarzan novels but missed The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby! One purpose behind my classic novel goal for 2023 was to patch a few of those holes.

But that’s just the point, isn’t it?

Along with those holes, I also acquired a thirst for learning and reading. I can fill those holes anytime I choose. But what about the kids who “have got nothing out of school but a hatred of books,” as Montaigne said, slugging their way through required reading and then rarely picking up a book once they’re done? They’ll choose Netflix.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Enjoyed this and quite agree, though I chuckled a little at your distain for Swiss Family Robinson. That was a book I read multiple times "on my own time" while growing up. Only fond memories here!

I'm a high school math teacher, and this summer the faculty read was Neuroteach, by Glenn Whitman and Ian Kelleher. It's all about how we can use the latest discoveries about brain science to improve teaching. Interestingly, they recommend using the classical Trivium - Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric - as a good framework for applying mind/brain/education research in the classroom. Those ancients were onto something!