American Mythos: Why the West Still Beckons

The Cost of Vengeance: Reviewing Aaron Gwyn’s ‘The Cannibal Owl’ and Derrick G. Jeter’s ‘Blood Touching Blood’

As Bailey English descends the steps of the frontier trading post, he bumps into a man who greets him with a knife—plunging the blade deep into his belly. The assailant walks off without consequence, and the newly orphaned Levi is the only one left to bear the burden.

The boy’s aunt and uncle step in to raise him, but their home proves hostile and Levi runs away. Where to? He sneaks into the camp of unsuspecting Comanches. Impressed by his moxie, they let him live. Under the protection of the chieftain Two Wolf, they even let him stay. And when band leaves to follow the buffalo, Levi follows too.

Myths We Live By

A myth is a story that enables us to tell elevated and abiding truths about the world and our responsibilities within it. Myths happen outside of time and transcend it. But stories of a particular moment can take on mythic qualities and become timeless theaters for the drama of human existence.

Depending on how you define it, every nation has their body of myths—some of which might be based in literal, historical truth, others of which are not. The classic examples? Gilgamesh, the Greco-Roman gods, Odin in Asgard, Finn McCool and the Giant’s Causeway, Arthur and Camelot. We can even think about Abraham, Jacob, and King David in these terms, as their stories have transcended their original settings and contexts.

But these come from ancient civilizations. What about America? Our nation is relatively young. And while we have the Pilgrims and the Founders and several towering figures from those early days, they don’t readily lend themselves to myth-making; there’s nothing easily timeless about them. Not true for, as I count them, two bottomless reservoirs of American myth.

I’m talking about the Mafia and the West. I’ll save the mob bosses and gangsters for a future post. Today, I want to talk about cowboys and Indians.

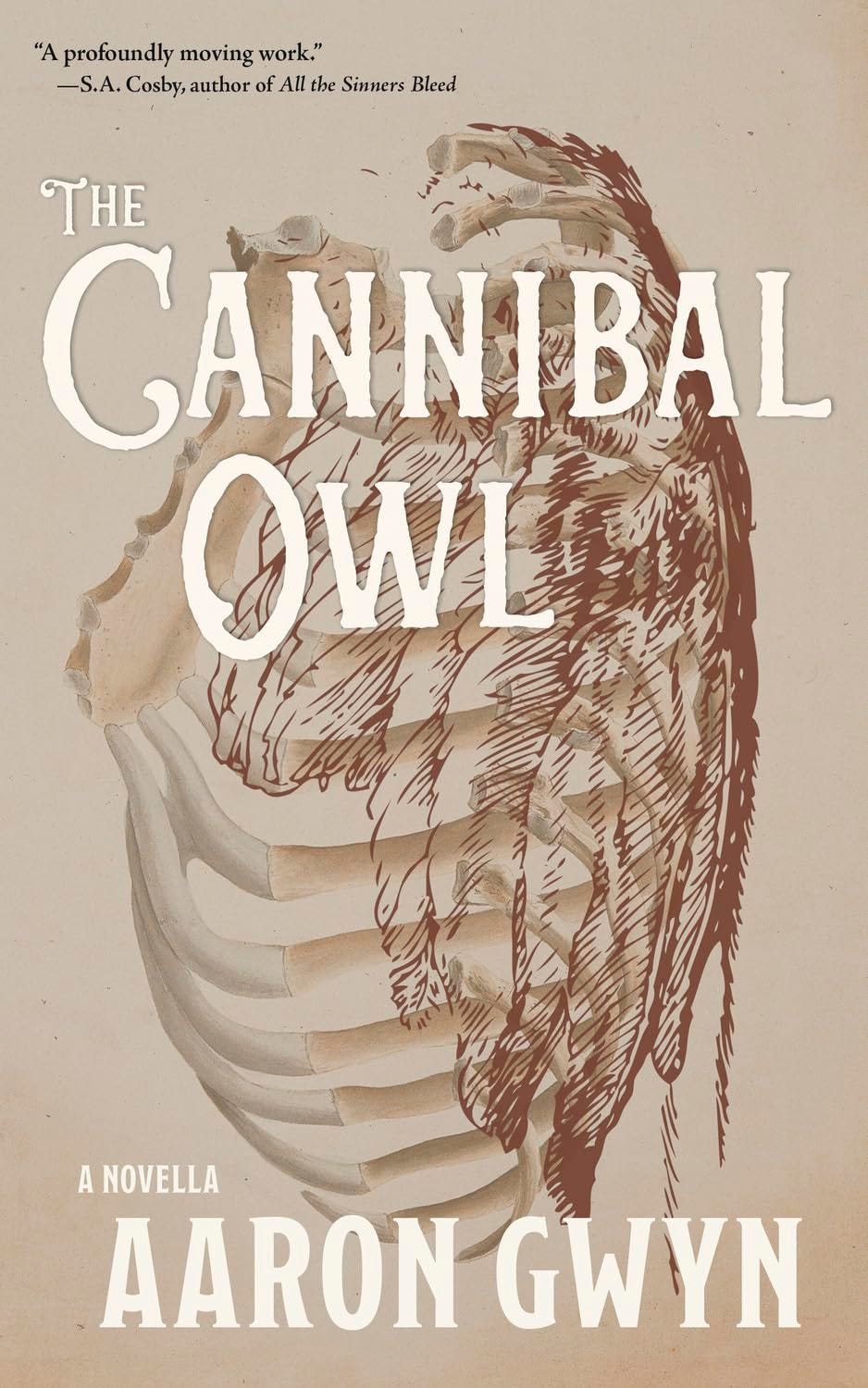

‘The Cannibal Owl’

Aaron Gwyn’s novella The Cannibal Owl begins with the death of Levi English’s father, Bailey, and the boy’s ambivalent adoption by a band of Comanches. The peacetime chief Two Wolf embraces him, the boy learns their language and customs, and he forms a tight bond with the chief’s father-in-law Poe-paya and Two Wolf’s wife Morning Star.

Others regard him with indifference or suspicion—especially the war chief Turns in Sunlight, who counsels against welcoming Levi into the band. The rift in the community grows as the story progresses.

Hovering somewhere above, haunting the imagination of young and old alike, is the Pia Mupitsi, the Cannibal Owl, a cross between a loving but stern mother and the Angel of Death. Comanche parents invoke Mupitsi to chide their children. Warriors invoke her to embolden them in battle.

When Levi makes a flippant comment about Mupitsi, Poe-paya takes him to fossilized remains embedded in a cliff—a mammoth—and imaginatively traces the shape of the bird in the bones. “She is not something to be mocked,” he says.

Nor should one mock the strength of the peacetime chief, Two Wolf. When his second wife secretively shifts her loyalty to his rival, the war chief, it signals the band’s unraveling unity. Two Wolf surprises Turns in Sunlight with a blow to the head and creates a mortal foe who bides his time before exacting revenge.

Poe-paya senses trouble but can do little about it. The old man is dying. He tells Levi to flee the band with Morning Star, fearing for her safety should Turns in Sunlight unseat Two Wolf. But Levi can’t do it. When Poe-paya dies, he grieves the only man who truly fathered him, but he cannot bring himself to tell Morning Star of her father’s warning. He stalls, tongue-tied, waiting for the right moment—until he runs out of time.

Turns in Sunlight and his followers attack Two Wolf and send the camp into chaos. When Levi thinks Morning Star has been murdered in the fray, he prays for Mupitsi to indwell him as he attacks the killer, firing an arrow through the man’s throat and fleeing with his scalp.

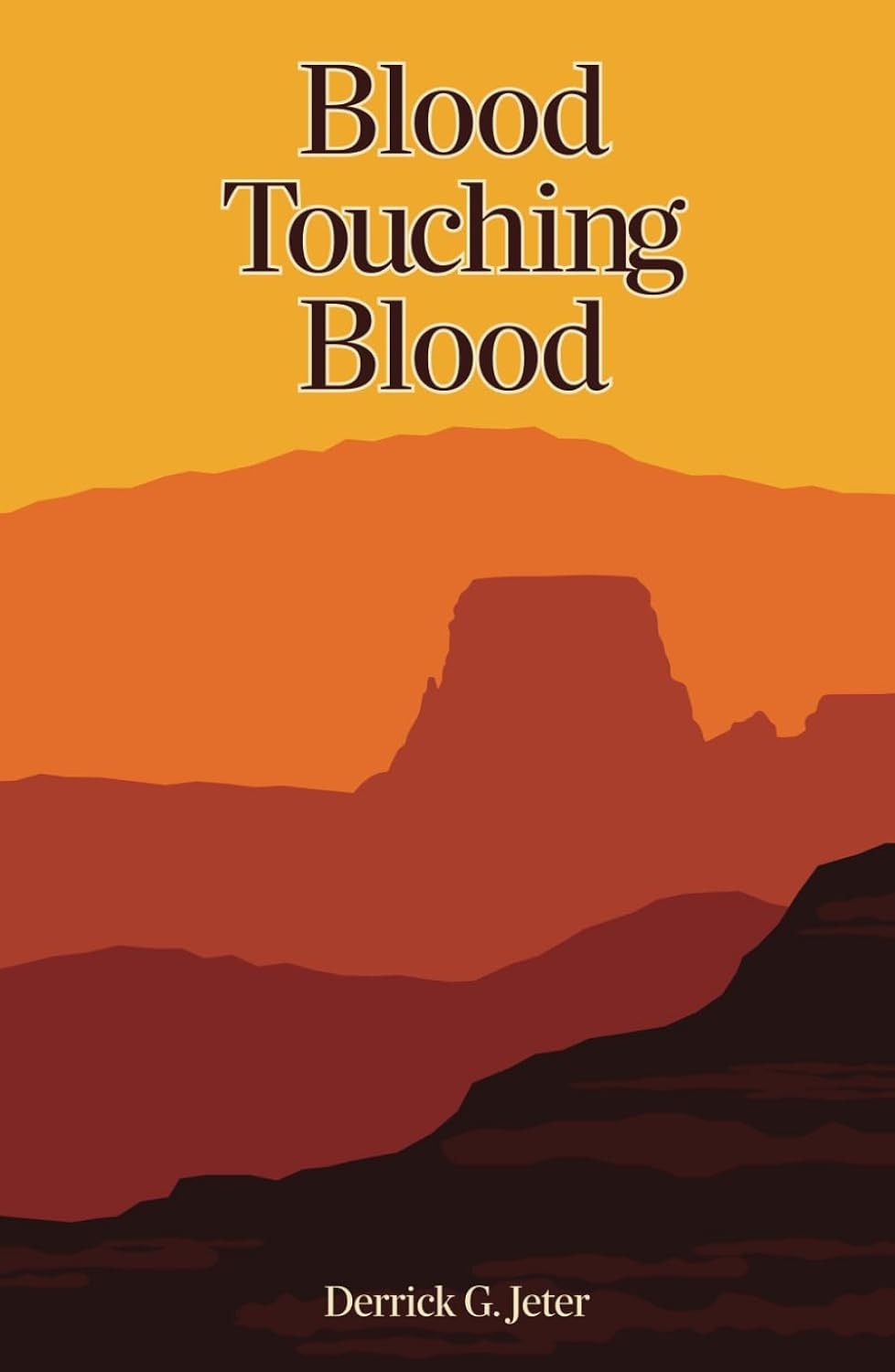

‘Blood Touching Blood’

In Derrick Jeter’s Blood Touching Blood, Col. Ethan Pendleton finds himself stationed at a Ford Davis in the West Texas desert, charged with pacifying the local Apaches—easier said than done when their leader Victorio and his men stalk the wastes. Victorio has recently murdered one of Pendleton’s men, flayed the skin off his feet, castrated him, and stuffed his bloody manhood down his throat.

Pendleton is dead set on vengeance. The fort physician, Dr. Elijah Anderson, counsels otherwise. “Violence begets violence,” he tells him. “It’s the devil’s own business. If you persist in it, you’re a damn fool. . . .” Pendleton knows better. He’s devout enough to take the scripture’s warning about revenge seriously—but not devout enough to heed it; the history goes back too far and the wounds run too deep.

Fifteen years before, Pendleton lost his new bride, Isabella, to the Apaches—to Victorio in fact—though he didn’t know it at the time; Victorio now wears her ring around his neck even. Ever since, he’s been ruthless in the prosecution of his duties.

How ruthless? “Colonel Pendleton has notions about Indian affairs that don’t square with official policy,” Dr. Anderson explains to a young lieutenant recently posted to the fort. Pendleton scalps his foes, pulling back their hair, slicing below the hairline, and releasing the skin with a pop. Gruesome and immoral, it’s “his way of honoring the memory of his wife and the troopers that died that day.”

The young lieutenant, Caleb W. Dancy, is a fish in the wrong pond. Fort Davis is in the middle of nowhere, manned by African American troops—“either former slaves or the sons of slaves”—with whom he can’t identify, and led by a colonel who can’t keep his knife off Apache forelocks.

But there’s little time to take the matter up with Washington because Victorio is on the loose and causing mayhem. Most of Blood Touching Blood involves a lengthy cat-and-mouse chase in which Victorio repeatedly strikes and eludes capture by Pendleton and his soldiers, adding to the body count with every encounter.

The False Promise of Revenge

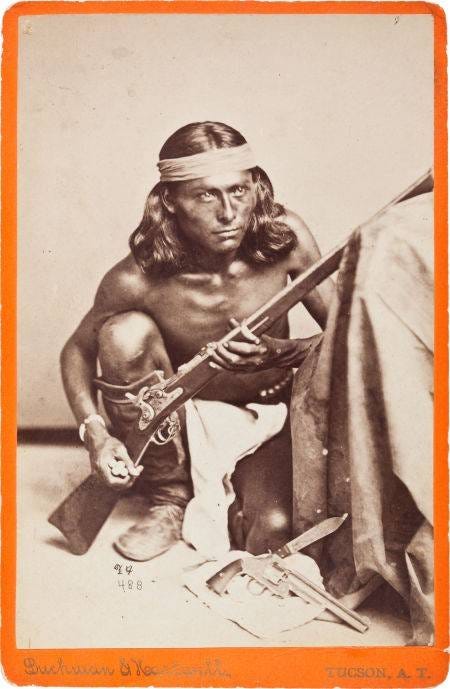

Gwyn and Jeter ground their respective novels on historical facts and persons. Levi English was a real-life settler who fled his home to live with the Comanche, and Gwyn has steeped The Cannibal Owl in Comanche lore, language, and customs. Though fictionalized, the story resonates as profoundly real, fundamentally true.

The same is true for Blood Touching Blood. Jeter explains that he first encountered the story of Col. Albert Pelton (Ethan Pendleton) and his affair with a Spanish girl named Bella (Isabella) in an 1883 edition of the Daily San Antonio Express and based several figures, including Victorio, and skirmishes with U.S. troops on actual engagements, though all of the details have been worked over to serve the story he wants to tell.

The events of history become the seeds of myths precisely because those events transcend history. They awaken the moral imagination and draw us into dramas that say less about the times in which they’re set and more about ourselves and the worlds we inhabit.

Both novels, for instance, turn on the question of revenge. When Levi escapes the slaughter of his friends, he solicits the help of Anglo Indian hunters to return and finish Turns in Sunlight. Once they track them down, Mupitsi indwells Levi again and they slaughter them all. But he has miscalculated. The attackers have killed the only person in the camp Levi loves, someone he thought was already dead: “I wanted to find my people, he heard himself say, then he realized he’d spoken in Comanche and they just killed everyone who might have understood him.”

In the case of Pendleton, his pursuit of Victorio nearly gets himself killed. But more consequentially, he bears the injuries of his own hatred. As Dr. Anderson warns him earlier, “Butchers butcher themselves long before turning their butchery on others.” When Lieutenant Dancy uncovers a surprise that turns his commander’s mission on its head, it’s almost too late for the colonel.

Vengeance masquerades as justice but fails to satisfy. By taking us out of ourselves, myths brings us to ourselves. What do they say about us as a people? What do they say about us as individuals? They invite reckonings with our passions, our personal failings. Would we feel vindicated in exacting revenge? A myth can remind us we would be disappointed—likely destroyed—by the effort.

The American Southwest is a mythic landscape full of mythic stories, a deep well to which our culture repeatedly returns to face the inescapable truths of our own existence. Levi and Pendleton are skeletal figures given flesh and spirit by novelists; as such, they’ve become mirrors of our own appetites and impulses—appetites and impulses that can devour both others and ourselves.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend. Or an enemy. I don’t discriminate!

And! More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

While you’re here and thinking about the mythos of the West, might I suggest . . .

Derrick Jeter? What?! He could write and play baseball?! Oh, okay, a different Jeter.

There is a resurgence of interest in the literature of the West. The Manichaen sense of good and evil in many Western stories was relevant in the Cold War period and may be relevant again now.

Here in the East, everything gets pulled down into the earth. Stories are muffled and hushed beneath the fallen leaves and branches.

In the West, everything sits on the surface. Stories remain, if not the thing itself.