The Terrible Books of Terrible Men

My Conversation with Daniel Kalder on What He Learned While Reading Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Gaddafi, and Other Prolific Despots

As someone who values human freedom as my prime political concern, I’ve spent considerable time reading about its opposite. Despotic fanaticism has always fascinated me. What, after all, drives people to extremes, both leaders and followers? This perverse preoccupation was especially intense during my twenties—though you can only take so much before needing a break. I nowadays pop in and out of the subject as the mood strikes.

It struck hard in 2018 when I encountered Daniel Kalder’s The Infernal Library: On Dictators, the Books They Wrote, and Other Catastrophes of Literacy, a book which flies under the title Dictator Literature in the UK. Evidently a masochist, Kalder subjected himself to reading the manifestos, memoirs, treatises, fiction, and poetry of a merciless string of sadists: Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler, Mao, and more. So many more. He is now, as he says, “the world’s leading expert on dictator literature.” That’s a thing? Yes. And, amazingly, Kalder skims off gobs of hilarity for his readers in the experience. The Infernal Library is an unexpected hoot. Mirth is a potent palliative to misery.

Besides The Infernal Library, Kalder has also written Lost Cosmonaut: Observations of an Anti-Tourist and Strange Telescopes. He maintains Thus Spake Daniel Kalder here on Substack, as well as a personal website documenting his journalistic (mis)adventures. As various authoritarians continue to rear their heads across the globe, I decided it would be, er, fun to chat with Kalder about it.

There’s something darkly comic that these mass murderers all believed themselves to be deep thinkers, even literary talents. Based on your time with this body of literature, what would you say are the psychological quirks that lead to that level of grandiosity?

Many of the dictators in the book were writers and intellectuals before they came to power, so they started out with grandiose self-conceptions. Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Mao, Khomeini, and Ho Chi Minh (among others) had all knocked out books prior to their dictatorial careers, and some of them had extensive bibliographies. Although each is terrible in his own way, they all shared a penchant for Manichaean simplifications, Millenarian thinking plus a hefty dose of resentment.

What possessed you to actually read these books? Was there a specific moment you realized, “Yes, I need to spend years reading Chairman Mao’s poetry, Saddam Hussein’s historical romances, and all the rest”? How did this project develop?

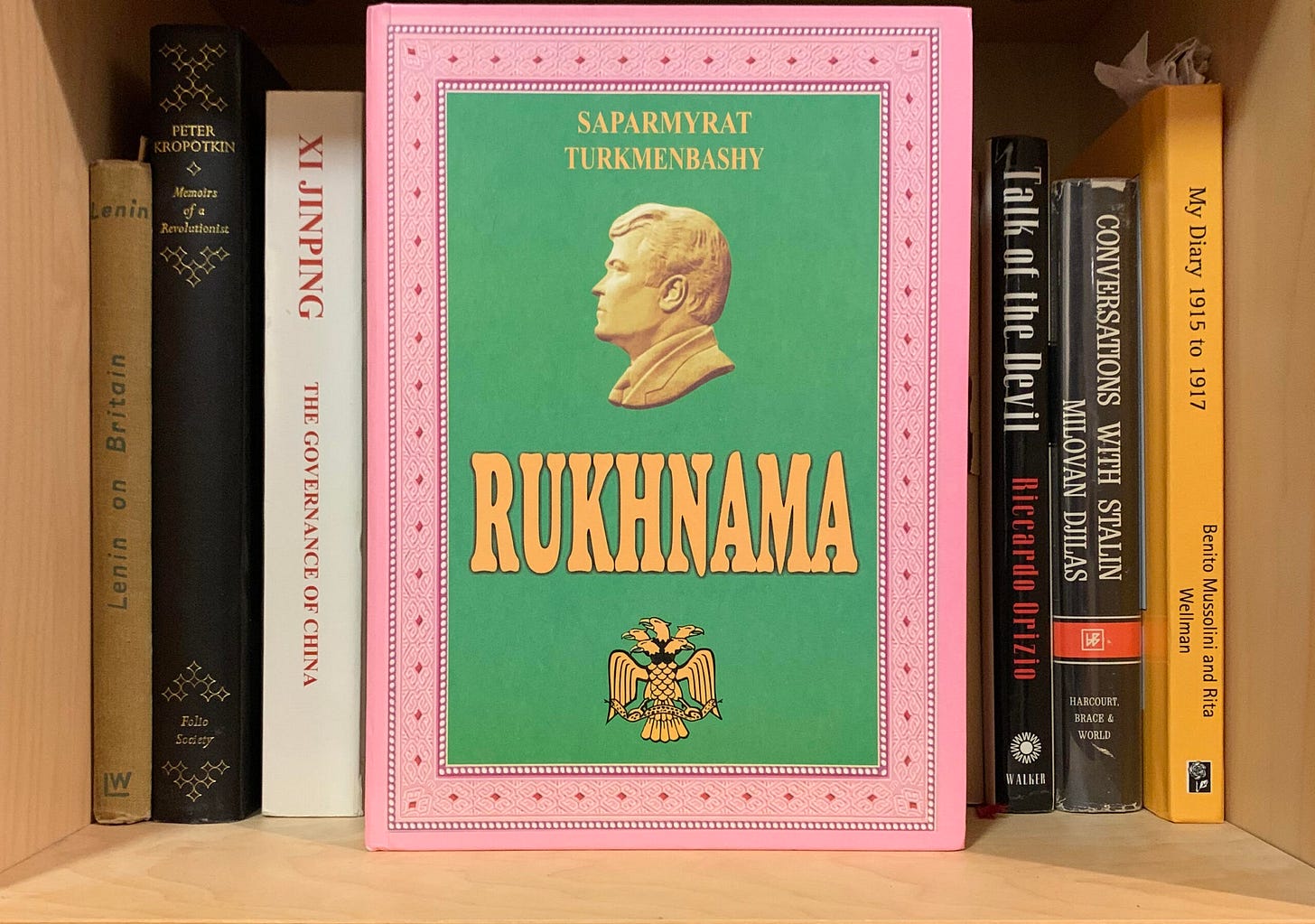

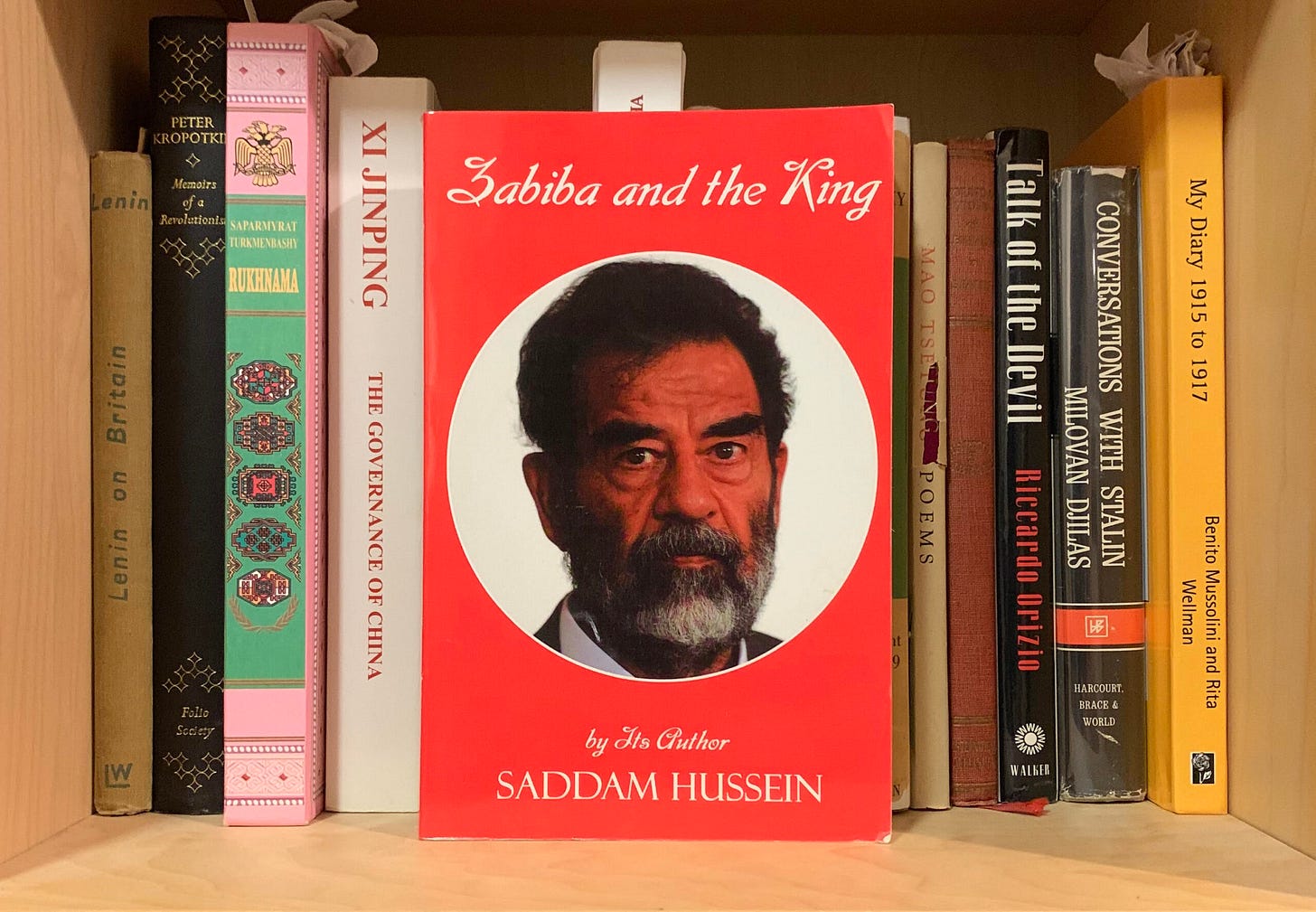

In the early 2000s I was living in Moscow. One morning I switched on the TV and saw a report from a country filled with gold statues of a dictator I did not recognize. The citizens appeared to be worshiping a book with the dictator’s portrait on it. This turned out to be The Ruhnama, or Book of the Soul, by Saparmurat Niyazov—AKA Turkmenbashi, the eccentric dictator of Turkmenistan. I had thought the dictator book was a dead phenomenon until that point. Eventually, I traveled to Turkmenistan where I discovered the bookshops sold pretty much nothing else besides Niyazov’s masterpieces. Around the same time, I received Saddam Hussein’s romance novel, Zabiba and the King for Christmas.

Having discovered these fantastically strange books, I began to research the history of the dictatorial canon and discovered that in the twentieth century nearly every despot worth his salt had put pen to paper—and that, contrary to popular belief, many of them were their own work. At first, I thought that reading them might give me insight into the psychology of great megalomania and evil, although I was quickly disabused of that notion as the last thing dictators want is to be humanized.

Nevertheless, I thought there was something worth studying here, but I needed an incentive to actually read the books as they were so bad. So, I pitched The Guardian on a blog series, and it was quite popular. That was when I started to think that maybe there was a book in it, although I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It took me around eight years to get that particular boat over the mountain, Werner Herzog style.

What was your method for assembling the list of books you would read and how did you manage the reading and writing itself?

Initially it was quite random—for The Guardian I focused mostly on “exotic” dictators like Enver Hoxha and Kim Jong-il and Emomali Rakhmon of Tajikistan because I am instinctively drawn to the outré and obscure. Once I decided to write the book, I realized I was going to have to become much more systematic as I was essentially writing a cultural and political history of the twentieth century through the lens of these terrible tomes.

I researched each dictator’s bibliography and then started buying copies from booksellers on Abe.com. That got to be quite expensive, so eventually I got myself a library card for the University of Texas at Austin, which had a surprisingly decent selection of very boring books by minor Eastern European dictators in the stacks.

As for managing the reading and writing, I just forced myself to read it all. I took Mao with me to McDonald’s, Stalin to hipster coffee shops, and Mussolini to a catfish joint. I would read and write after work until the early hours of the morning and then polish the drafts on Saturdays and Sundays. Extreme boredom was an essential part of the process; the books were not designed to be enjoyed, after all.

Which dictator’s writing was the most unexpectedly good? And—horseshoe!—which was so colossally bad it became almost glorious in its awfulness?

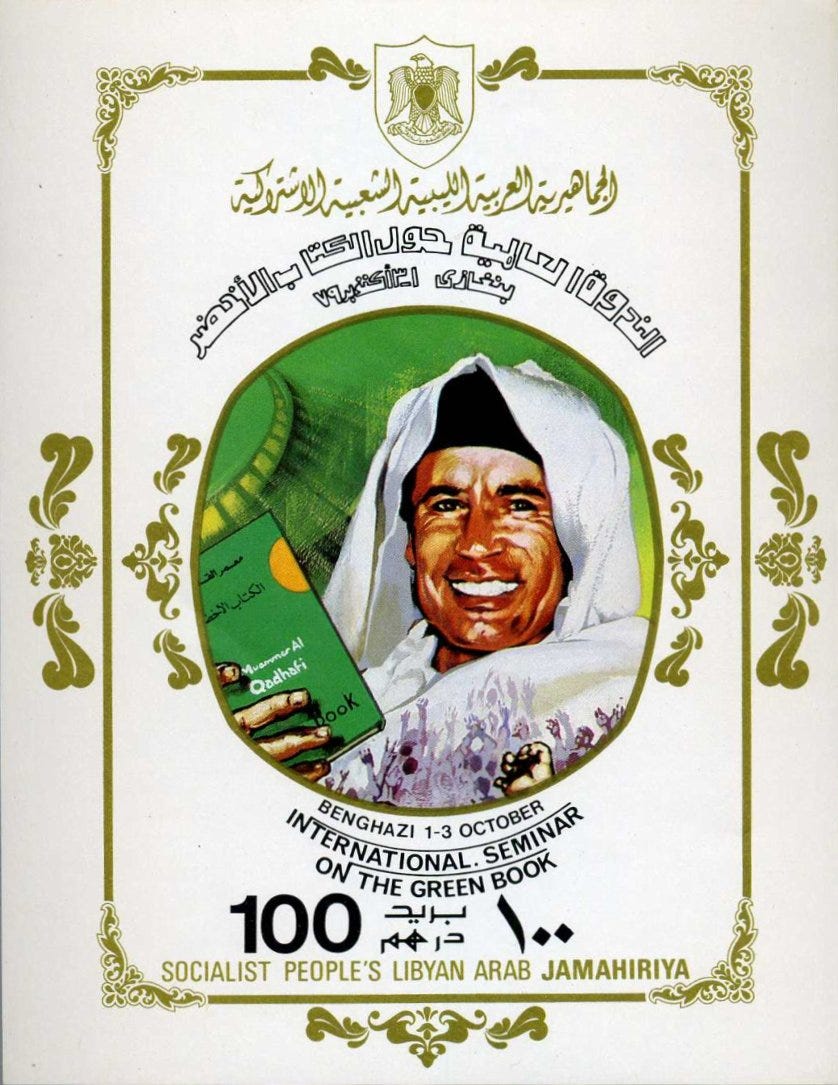

Mussolini was a highly successful journalist and editor before he became a fascist despot, and he understood how to engage an audience. His war diaries are highly readable, and his biography of Jan Hus and even his potboiler, The Cardinal’s Mistress, all contain striking passages. As for the gloriously awful, it’s a toss-up between The Ruhnama and Gaddafi’s Green Book. The Ruhnama has some entertainingly bad poetry, but Gaddafi’s book probably edges it out for its bizarre digressions, including a memorable section on gynecology.

Who was the absolute worst?

Mein Kampf is exactly what you’d expect—pages and pages of hateful, monomaniacal ranting. Hitler only wrote it because he was in prison and had a lot of time on his hands. Perhaps he felt he had to outdo the communists, who were all extremely prolific writers. One of the quotes I begin the book with is his: “I am not a writer.” Even he knew it wasn’t very good.

Did you read anything else while you were reading this literature to balance it out? Did you need a purgative of some sort after you were done?

Since I was fifteen I have kept a record of every book I have read. However, for the years during which I was most intensively hammering away at The Infernal Library the pages of my notebook are blank. When I look in the bibliography of my book, however, I can see that I read a great deal during that period. It was all dictator texts, or secondary sources on politics, history, religion, and so on. There wasn’t time for anything else.

In the immediate aftermath I mostly read 1970s Conan comics and developed a great appreciation for the art of John Buscema. A little later I was selecting books from my university days for donation when I stumbled upon my old copy of Ted Hughes’s Selected Poems. I opened it, and the vibrancy of Hughes’s work, and its connection to the British landscape, blew the top of my head off. Probably it was one of the poems all British school kids of my generation had to study, like “Pike.” Later I got deeply into his “Crow” cycle, which I highly recommend. After subjecting myself to so much oppressive, dead language, Hughes’s verse was a revelation and, I think, a liberation.

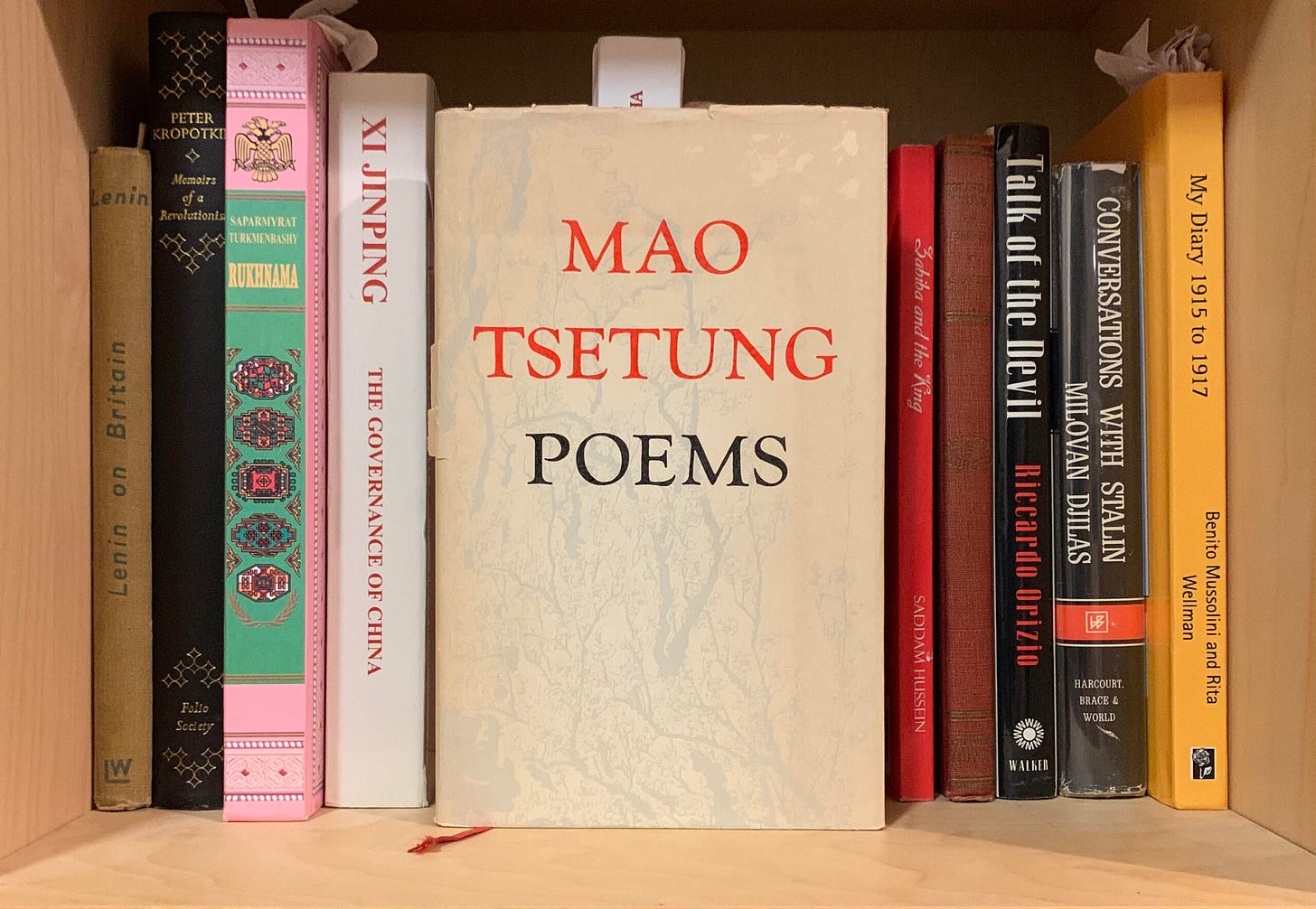

Lenin was actually a competent writer, no? Mao’s poetry had genuine admirers. How do you reconcile legitimate literary talent with monstrous actions? What lines do we draw and where?

You wouldn’t read Lenin’s prose for pleasure, but he was an effective communicator and had a knack for coining slogans. Mao’s poetry, to go by the translations, is okay. But of all those guys, only Mussolini had real talent, and even then, it was as a journalist, cranking out hot takes and the like. There are really great literary writers like Yukio Mishima or Russia’s Edward Limonov who also had extreme political beliefs, but fortunately they never got anywhere near power.

Having encountered real literary skill in service of diabolical purposes, how do you think about the power of rhetoric? Did you finish this project thinking differently about how words work in the world?

I was amazed at how, over the course of a few decades, completely marginal ideas successfully moved to the center. At one point the Bolsheviks were so unpopular and obscure that they had fewer members than the Skopts, a nineteenth century sect that castrated its members in order to hasten the second coming. Before too long they were running the largest country on the planet.

Rhetoric is not enough, you need a charismatic leader, organizational skills, ruthlessness, the right opportunity, and so on. But we should not underestimate the ability of some to mold reality through language (including language that is inelegant and boring), nor the desire by others to be so seduced.

What are the tells a strongman is getting high on his—it’s almost always a man, right—own supply? Is it even possible to spot lethal literary ambitions, or is that something we can only see in retrospect?

When the books attain the “sacred” status equivalent to The Bible or The Koran you know you’re in trouble. The early Bolsheviks were willing to debate with each other, and this was also the time when the Russian avant-garde was at its peak. Mayakovsky, Meyerhold and Malevich were still doing interesting work. But by the time Stalin effectively canonized Lenin there was only one acceptable interpretation, the one laid down by him, and everyone had to agree with it. Once “the truth” was beyond discussion, all interesting writing was done for the desk drawer. Alas, by the time this happens, it’s always too late to do anything about it.

You lived in Russia for, what, a decade. Did that experience provide a helpful lens for reading Lenin and Stalin? How did that change your perspective, as opposed to someone coming at them cold?

I arrived in early 1997, just a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union so I was living in the wreckage of the world that Lenin and Stalin had built. I knew what the food tasted like, what the music sounded like, how shabbily the apartments were constructed, which gave my understanding of Soviet and Russian culture a very visceral quality.

Everyone I met had been raised in the Soviet system, so I learned about it directly from the people who had experienced it, while also reading deeply and traveling widely. I was deeply immersed in Russian and post-Soviet culture, and as a result I was able to write those sections quite quickly because I had so much context and was very confident in my judgments and analysis.

What about dictator literature from cultures you were less familiar with?

In The Infernal Library I play on T.S. Eliot’s idea of tradition and Harold Bloom’s theory of the anxiety of influence. A lot of the dictators were indeed influenced by each other and followed the templates laid down by their predecessors. In those instances, I able to get to grips with the books quite quickly, even if they were from cultures with which I wasn’t quite as familiar.

On the other hand, some of them were operating in different traditions, with different assumptions, and in those instances it took me longer to feel confident in my analysis. The Ayatollah Khomeini was challenging because, although I am reasonably knowledgeable about Islam, I was completely unfamiliar with the Velayat-e faqih, which is central to his theory of government, and which was derived from an “innovative” interpretation of a very specific aspect of Islamic jurisprudence.

Perhaps the most challenging dictator to write about, however, was Chairman Mao. His Marxist jibber-jabber was as boring as that of any Soviet dictator, but the apparent familiarity could be misleading. He deviated from the Soviet line early on, and his work also had to be read in the context of Chinese literary culture which is thousands of years old. Should I read Mao as a dictator author in the Marxist theoretical tradition, or as one in a long line of emperor-poets?

His books were also central to the Cultural Revolution which I think is poorly understood in the West. Some of the details were fantastically strange and like nothing you find in Soviet history, even at the peak of Stalin’s personality cult—there were reports of sick people being cured of cancer after reciting Mao’s dictums, for instance.

You wrote The Infernal Library before our current resurgence of strongman politics. The fringe again seems to be migrating to the center. Does your exploration of dictator literature give you any insight into today’s political moment?

I am often quite surprised at how many disastrous ideas from the previous century have reemerged in reheated form over the past decade or so. Maybe humans just don’t have that many ideas and we are doomed to repeat ourselves. As I said, there is no concept so crazy or marginal that it can’t infiltrate and overrun reality, at least for a while. That said, I am wary of drawing too many parallels between the situation one hundred years ago and today. The “everything I don’t like is Hitler” school of political analysis is very stupid and obscures rather than illuminates.

Would the general reader find any benefit in these books? What three should we consider sliding into our TBR pile? And how much of a masochist need one be?

I had an idea for a follow up called Business Secrets of the Dictators in which I would apply the lessons of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, et al. to climbing the corporate ladder. Ruthless capitalists could learn a lot from dictators when it comes to gaining and exercising power, and I liked the idea of setting Lenin spinning in his catafalque.

Saddam’s romance novel, Zabiba and the King, probably gives you the most insight into the loneliness of the long-distance dictator, as he wrote it after falling in love with a much younger woman and he allows the king character to speak quite openly about his isolation and fear.

Finally, Putin once coauthored a judo manual, which might be quite useful if you’re interested in throwing people about.

Final question: You can invite any three authors—dictators or not—for a long meal to discuss whatever strikes your fancy. Neither time nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how would that conversation go?

I’d pick Robert Irwin, Thomas M. Disch, and Christopher Priest. Irwin is perhaps best known as a scholar of Arab history and culture (he edited the Penguin edition of The Arabian Nights), but he wrote numerous esoteric yet highly entertaining novels. Priest and Disch both emerged from the New Wave of Science Fiction scene that was centered around Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds magazine in the 1960s but always ploughed their own furrows and produced many excellent novels and short stories that are unlike anybody else’s (including each other’s).

All three are now dead and, although they produced work of exceptional quality, they are not famous enough to receive critical biographies, so I would use the dinner as a chance to ask them all the questions I have about their work that will never be answered. All three were also witty, erudite and highly opinionated, so once I had my questions out of the way I don’t think I would have to do much to keep the conversation flowing.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends—or any despots you might know.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

A follow-up project might be to contrast the self-obsession of dictators with the perspective of their underlyings. I read the memoir of Rudolph Hoss, commandant of Auschwitz - if Hitler was self-obssessed in his writing, Hoss was self-decieved, never taking full responsibility for the atrocities, while also obsessing over the details of how those atrocities were committed.

Thanks for reading all that shit so I don't have to (Hilter and Moa excepted).