When Your TBR Is LOL, Try DNF

Who Says You Have to Finish Every Book You Start?

In Alan Bennett’s novella The Uncommon Reader, a fictional Queen Elizabeth borrows a difficult book from a mobile library and grinds out the pages before returning it.

“How did you find it, ma’am?” asks the librarian, who admits trying and abandoning the book.

“A little dry,” says the queen. But, she adds, “once I start a book I finish it. That was the way one was brought up. Books, bread and butter, mashed potatoes—one finishes what’s on one’s plate. That’s always been my philosophy.”

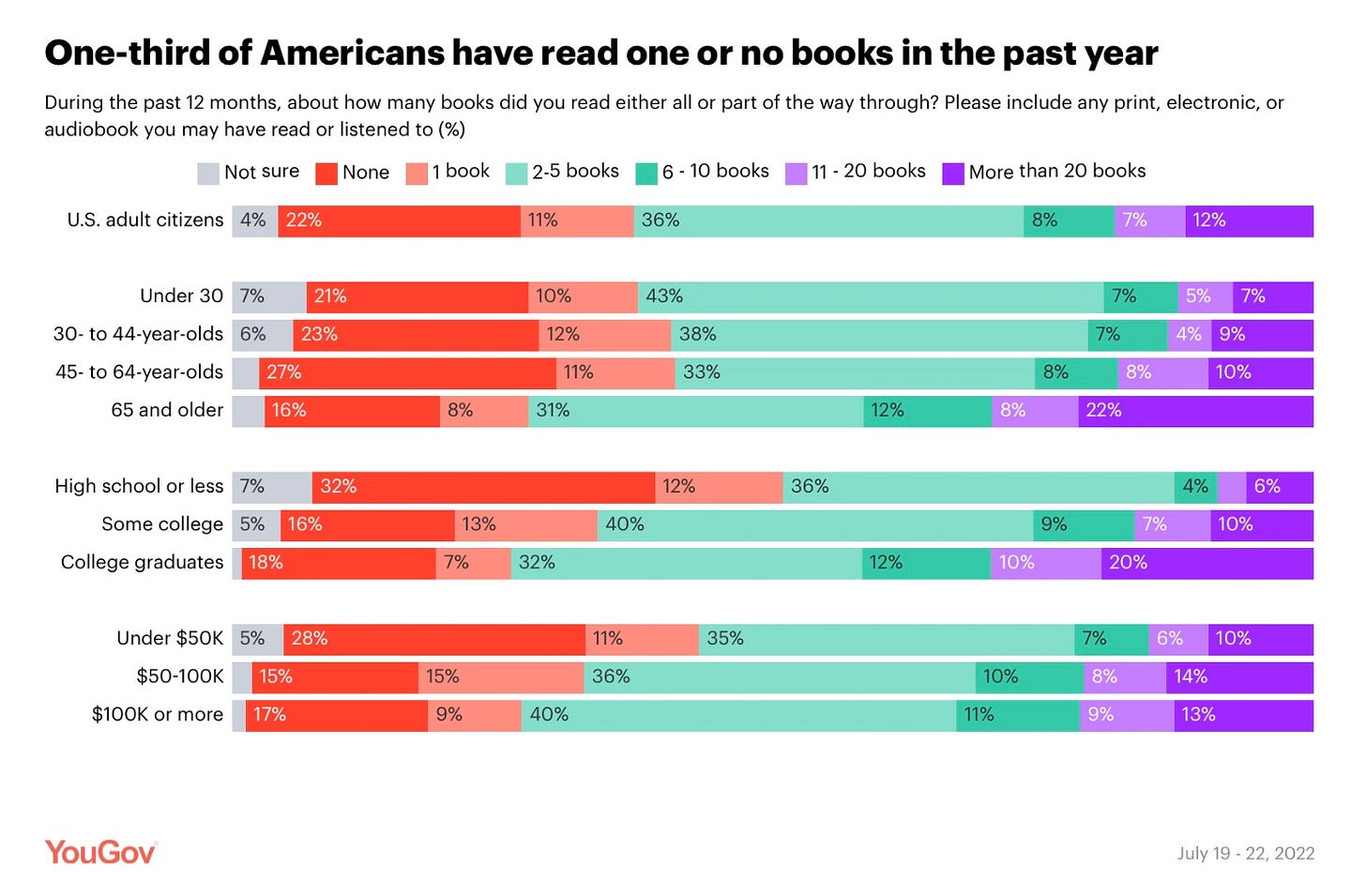

While the queen might be uncommon, her determination to finish what books she begins is not. In fact, a YouGov poll shows a solid third of U.S. adults reports “always” finishing a book once they start. The older a person is the more likely they are to feel the need to reach the end; you’re almost twice as likely to finish a book if you’re over 45 than if you’re under 30.

There are certainly those who ascribe high value to finishing. “I finish every single novel I start,” says Juliet Lapidos in the Atlantic. “When I decide I’m going to read a novel, I read the whole thing.” She expresses concern about people who “think nothing of dropping a novel halfway because they find it boring . . . or because they forgot it on the subway and moved on to the next thing.” Such behavior, she says, “seems lazy to me.”

On the positive side, Lapidos offers three reasons readers should see a book through to its last line: pleasure, fortitude, and respect. When we slog through a sleeper, we sometimes discover something surprising by the end that provides enough joy to justify the time. If that pleasure proves elusive, there’s also the improved mental stamina that accrues to extra intellectual effort. And finally, finishing demonstrates respect for the author’s effort—and, really, for the entire literary enterprise.

Okay. But I’m unconvinced.

I’ve always been one who supports bailing on a book that doesn’t deliver. Lapidos knows why. “There are more good books than any one person could possibly read,” she says, voicing my view to a T; “it’s stupid to waste time on a dull or otherwise unsatisfactory novel.” Indeed. But Lapidos says we should simply avoid lousy books to begin with.

I find that oddly moralizing. We’re in finish-your-mashed-potatoes territory. What if I just explore what books interest me and then switch if they fail to sustain my interest? No harm, no foul.

Library employee Emily Barber backs me up on this one. If your TBR is LOL, Barber suggests DNF: do not finish. “Take a moment to consider why you read,” she says. “If you’re among most readers who are seeking joy and enrichment, chances are not every book you power through is bringing you closer to that purpose.”

She’s right. Giving precious time and attention to books that suck up the former while barely holding the latter is the literary equivalent to the sunk cost fallacy. We read for a desired return; if there’s no return, then it’s not worth the investment. Bail.

Ask yourself: What would you do with your remaining time if you didn’t waste it by dragging your poor eyeballs through a genuine plodder? ”You might end up reading more books,” says Barber; that’s exactly why I advise quitting in “9 Tips to Read More This Coming Year.” For the time it takes you to finish a book that might induce tears in lesser mortals, you could have finished two, even three, better books. Consider the opportunity cost you’re incurring by sticking with the first.

Further, as Barber notes, dropping a book doesn’t mean you’ll never pick it up again. There’s nothing wrong with putting a book on hiatus and giving it another go at a later date. Reading always involves both the book and what we bring to it. If we’re unable to supply the right intention, attention, and whatever else might be necessary, then we can simply shelve it for the present.

In some cases that honors the book more than gutting it out. (“It’s not you, Dostoevsky. It’s me.”)

This provides a useful excuse when it comes to the classics. There’s an unevadible ought-to-ed-ness with the so-called Great Books and their literary cousins. By reading them, we rise to their stature. And there’s virtue in that. But not if we run falter a hundred pages in, slow to a crawl, and resent the whole thing. Better to jump to the next book on the pile and come back to it another day.

For me it all comes down to time and return. I read both for work and for pleasure. I’m more willing to muscle my way through a dense thicket of prose for work. Think of, say, a research project. I’m after defined insights, findings, arguments, revelations. I’ll happily finish a book by an academic who forgot how to write two degrees ago when I know why I’m doing so.

But reading for pleasure is different. In that case I’m also after insights, findings, arguments, and revelations—along with humor, pathos, and catharsis. But the outcome is undefined. I’m scouting. If I hit a cold trail, I can more easily find what I need by taking a different path.

Don’t discount easy. Most Americans read next to nothing (see below). Telling people they have to finish once they start discourages some from starting at all. Who wants to read with a sense of obligation hanging overhead? If people felt free to try on a book for size and then leave it in the fitting room if it doesn’t appeal, they’d probably try—and thus enjoy—more books.

Finally, there’s finality itself. We’re going to die. Memento mori, folks. If I read fifty books a year and I live another forty years, that’s just 2,000 before I conk, no matter how many books are left on my TBR. Of course, I could live longer than that; my great grandma made it to ninety-nine. And I might read more than fifty titles in a year; last year I read eighty-nine.

So, let’s say I’ve got more like 4,500–5,000 books in me. That’s still a relatively tiny number. Hundreds of thousands of new titles are published every year. An obligation to finish what I start fences in my exploration and limits my exposure to superior books—books that will provide more of what I’m after.

And for what? Because someone says it’s good for me? Because it’s like finishing my peas? No thanks. As I see it, quitting a bad or uninteresting book isn’t lazy; it’s prudent. It’s almost as profitable as minting time.

To my thinking, it also reflects a more nuanced view of reading, one in line with this observation from Francis Bacon’s Essays:

Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested; that is, some books are to be read only in parts; others to be read, but not curiously; and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention.

And the same goes for newsletters. If you finished this one, it must have been worth it. I appreciate your time. Please consider sharing this post with someone who might also enjoy it.

If you’d like to subscribe, you can do that here. I publish one new book review each Saturday and an essay like this on Wednesdays. Thanks!

Well said. There are more educated people and published books (over-published?) now than in centuries before so we must be selective! If a book is a classic that has earned its place on the Bestsellers of All Times list and I’m slogging through it, I set it aside. MADS. Maybe a different season. There is only so much time and that’s why I appreciate hearing from people like you who take reading seriously and with passion....as opposed the the five star amazon reader who whisks through a romance novel and declares it a masterpiece. And I’ve read one star reviews on books that earned a place on my shelves with a promise to reread.

I'm with you all the way. Typically if a book slows to a crawl or I'm thinking about a dozen other things while I'm staring at the words, I flip a few pages and see if it picks up. Ultimately, once I start doing that I find that I'm done.