Slow Down and Read: The Point of Poetry

Delightful Work, Phillis Wheatley, David Whyte on Poetry’s Psychology, Books My Grandfather Gave Me, More

¶ The benefit of friction. This week on EconTalk, host Russ Roberts talked with poet and cartoonist Zach Weinersmith about his new book, Bea Wolf, an amusing adaptation of the Old English epic poem, Beowulf. The conversation covers a wide range of ground, but one subject that gets a fair amount of attention concerns why people seem to undervalue poetry these days.

Weinersmith notes that a few generations ago people would regularly pepper their correspondence with verse, lines picked up here and there and then shared on the assumption recipients would appreciate the poem as much as the sender. “This used to be part of our culture,” says Weinersmith. “And somehow it got murdered, and I don’t know why.”

There’s evidence poetry has had a bit of a revival in the last decade, though the number of readers are still low. Only 12 percent of US adults have read a book of verse in the last year; in 1992, that number was 17 percent. As Roberts notes, poetry doesn’t come easy for most people. “Poetry often, not always, but often requires work,” he says. “And work is a bit of out . . . fashion.”

It’s not that poetry’s hard, exactly. The labor it requires of us is mostly one of slowing down. We’re used to scanning articles online, chasing our eyeballs down listicles, and hoovering up information. But poetry doesn’t reward rapidity. It invites lingering, savoring, sometimes wrestling, and usually rereading many times over.

Poetry’s very shape and sound cause friction for the reader or listener. Line breaks interrupt rapid decoding because they force us to recognize the author’s intended emphases and rhythms. Prose permits rapid scanning where the reader sets the pace. Poetry interrupts. It also serves up words whose meanings might appear obvious but which hide layers of nuance only accessible to those willing to turn them over several times.

If the pace and pressures of life feel unsustainable, poetry offers a temporary detour from the race—but, as Roberts suggests, you might have to work a bit for it. Increasingly, I find it worth the trouble. I recommend listening to the whole episode and have included the video below. And Bea Wolf sounds like a riot.

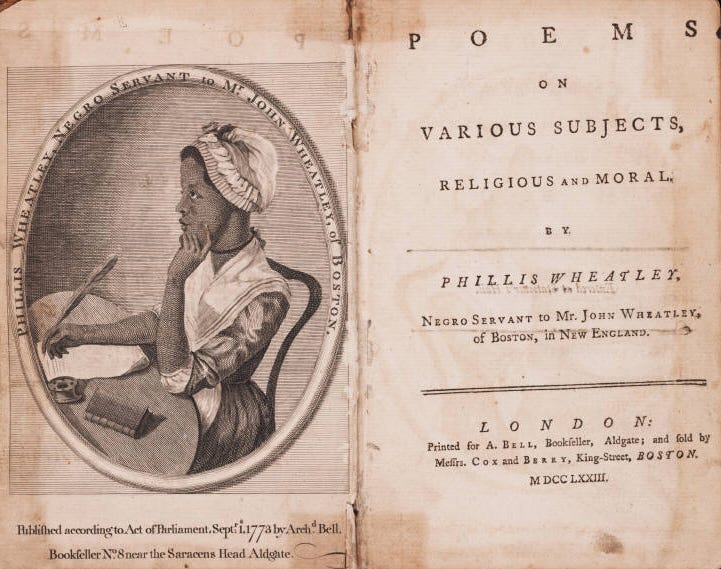

¶ Free verse. Phillis Wheatley was enslaved at the time her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in 1773. A brilliant and precocious child, she first published her work in a local paper when she was just thirteen years old. By 1773 she’d amassed quite a collection of verse and the publication—the first book of poetry by an African American—garnered her international fame and led to her manumission in 1774.

Along with making appearances in a recent review here, Wheatley also made news earlier this year when an Albany professor identified a hitherto unknown poem by her tucked away in a Quaker commonplace book.

¶ Words to rile and console. “When poetry is a backwater it means times are O.K.,” says poet Jane Hirshfield. “When times are dire, that’s exactly when poetry is needed.” Hirshfield is speaking of society-wide moments of trouble. And poetry can certainly serve a protest function, as Hollis Robbins shows in her history of black sonnet writing. But poetry works when times are individually demanding as well. Poet David Whyte explains why in a conversation with Psychology Today:

Poetry’s invitation is to bring the qualities we feel inside into conversation with what is occurring in the outside world. When those two come together, we experience it as beauty. There is always something beautiful about the truth in poetry, even when it’s difficult and frightening. Even in the asymmetry—when the world outside is beautiful, and, yet, we feel as if we’re dying inside. A poem extends the invitation to make the correspondence between inner and outer in that asymmetry. The poetic art is about living at the frontier between things.

You can’t rush that process—and it’s that process that can bring consolation amid tumult.

¶ A verse for adversity. “Can reading poems relieve the physiological symptoms of stress and anxiety?” asks science writer Marissa Grunes. Yes, as a matter of fact. “A series of studies have shown that reading rhythmic poetry can increase both your resting [heart rate variability] and cardio-respiratory synchronization,” both of which are correlated with “mental health, well-being, and even long-term resilience to stressors and trauma.” So, if you’re feeling stressed, try dipping into a poem or two. Also, check out this video.

¶ I have a few books of poetry once owned by my Grandpa Olson, including a collection of T. S. Eliot’s verse. He received the book as a Christmas gift in 1944. Appropriately, a small black-and-white photo of a hippopotamus marks the poem, “The Hippopotamus.” There’s no date on the photo. I received this one shortly after he passed away and his library was dispersed. I received his copy of A. E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad at the same time.

Then there’s this collection of Thomas Wolfe poetry, A Stone, a Leaf, a Door. My grandpa loved Wolfe’s books. He kept this one beside his typewriter, according to my Aunt Chris. Grandpa included two stanzas from Wolfe in my grandmother’s funeral service, and I think the lines were from this volume, though I’ve long since lost the program to check.

But wait, you say: Wolfe wrote novels, not poetry. True enough. A Stone, a Leaf, and a Door was published posthumously in 1945 (Wolfe died in 1938) and features passages from three posthumously published novels rendered in verse: The Web and the Rock, You Can’t Go Home Again, and The Hills Beyond. Many thanks to my mom and aunt for conspiring to get me this precious volume.

¶ If memory serves. My grandpa could quote line after line of poetry for hours on end. I don’t know where he kept it all or how those neurons followed the crumb trail back to his reading, but his memory was phenomenal. And he’d do it spontaneously—as context prompted. He owned seven acres in Fair Oaks, California, with several orchards, gardens, and patches of this or that growing here and there. As we’d work among the trees or digging up potatoes, something might trigger a recital: a bee, a butterfly, a shovel, almost didn’t matter. He had a poem for almost anything.

In his conversation with Russ Roberts, Zach Weinersmith recommends memorization:

I think is extremely valuable. . . . In order to memorize, you have to make sense of it. . . . It’s very hard to remember something that's just gibberish. It would be very hard to remember a 100 lines of nonsense. But, like, 100 lines of the Iliad is quite doable. . . . When you commit it to memory, it’s like putting a little room in your personality.

But isn’t memorizing poetry hard? Not according ot Weinersmith. “It’s very easy to memorize a lot of verses,” he says. “You'll surprise yourself. If you start trying to memorize something and just add a line a day, you would think would top out somewhere. And, it just becomes very natural. It’s part of your working knowledge.”

¶ I’d love to hear if you have any favorite poems or poets. Please share those in the comments.

¶ If you enjoyed this post, please consider it with a friend. Thanks!

¶ If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I love this post. Great work, and a wonderful story about innovation and pursuing dreams (or as we would say, "Listening to the still, small voice."

I have self-published two haiku poetry books. Some folks have never heard of it.

I am amazed at how much emotion you can express in three lines of poetry. It is

challenging to follow the 5-7-5 syllable count. It doesn't 'come easy' as you noted in

your article. Writing haiku is cathartic. I feel that it has a positive effect on your mental health

and overall well-being.